-

The Handmaiden (2016)

So intricately woven are the layers of deception in The Handmaiden, the cons that masquerade as plot become part of its very structure, staging a seductive dance between cunning swindlers and discerning victims that Park Chan-wook choreographs with masterful precision.

-

The Best Films of the 1910s & 1920s

The greatest films of cinema’s early years, from German Expressionism to Hollywood’s silent comedies.

-

Memories of Murder (2003)

Bong Joon-ho’s faceless serial killer may represent some abstract embodiment of moral corruption, but this violent perversion is clearly rampant in Memories of Murder, stranding us with a pair of under-resourced detectives navigating landscapes of mud, rain, and bureaucratic failure.

-

Sentimental Value (2025)

Nora’s scepticism towards reconciling with her estranged father may be justified in Sentimental Value, yet the power of healing through artistic collaboration is not to be underestimated, as Joachim Trier peels back layers of generational trauma to expose the tender vulnerability beneath.

-

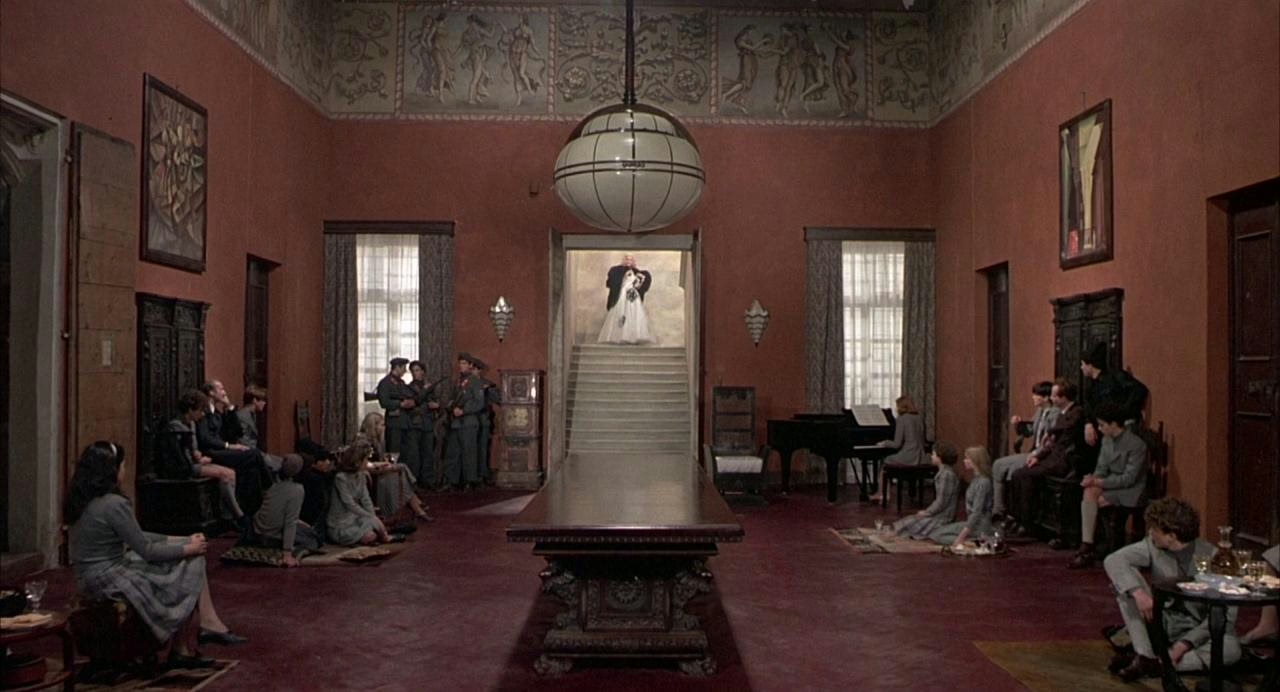

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)

Through Pier Paolo Pasolini’s formal severity and exacting aesthetic, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom stares unflinchingly into the repellent darkness of humanity’s soul, tracing the systematic torture of young captives subjected to the relentlessly sadistic games orchestrated by four fascist overlords.

-

Frankenstein (2025)

Through operatic mythologising and cinematic splendour, Guillermo del Toro magnificently elevates Frankenstein into a rueful, elegiac meditation on kinship, condemning both father and son to the same corrosive cycles of paternal cruelty, maternal absence, and a hunger for love that no creation can satisfy.

-

Elephant (2003)

Gus Van Sant does not strive to make sense of the senseless school shooting in Elephant, but rather attaches his tracking camera to the various perspectives of victims and perpetrators as it unfolds, delivering a chilling vision of violence that arrives without warning, logic, or resolution.

-

Mystic River (2003)

As Mystic River asserts cycles of shattered innocence through the abductions, abuses, and murders of one Boston neighbourhood, Clint Eastwood draws three childhood friends together over old traumas, and ensnares them in the simmering tension of fresh suspicions.

-

It Was Just an Accident (2025)

Jafar Panahi channels his fury at Iran’s oppressive regime into the complex moral dilemma of It Was Just an Accident, propelling a party of former political prisoners on a quest to identify a man they believe to be their torturer, and uneasily distilling the gnawing, unrelenting anxiety of their tortured survival.

-

Yasujirō Ozu: Family in the Frame

Earning the mantle of one of cinema’s great formalists, Yasujiro Ozu develops a distinctive visual language rooted in meditative pacing and meticulously composed interiors, evoking a Zen-like tranquility through which the subtle, unspoken tensions of domestic life quietly unfold.

-

No Other Choice (2025)

Never has Park Chan-wook wielded his fatalistic irony with such a darkly comedic edge as he does in No Other Choice, sending one unemployed paper specialist on a murderous trail against rival job candidates, and sharply exposing the bureaucratic nihilism of modern capitalism.

-

An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

If Yasujirō Ozu’s filmography is a cinematic suite charting the tension between tradition and progress, then An Autumn Afternoon stands as a tender final movement, tracing a widowed father’s reluctant push to marry off his daughter amid Japan’s mid-century commercialism.