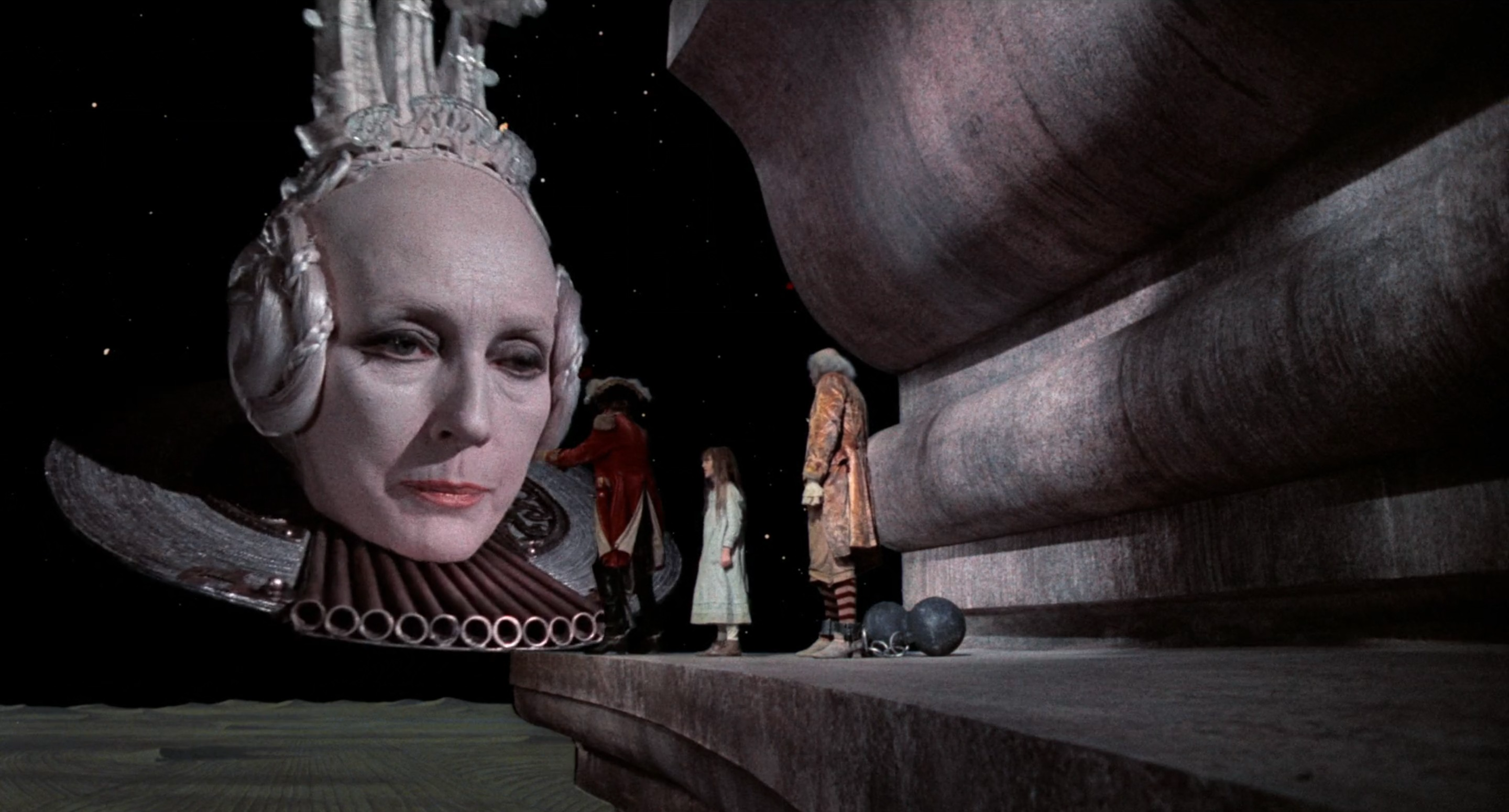

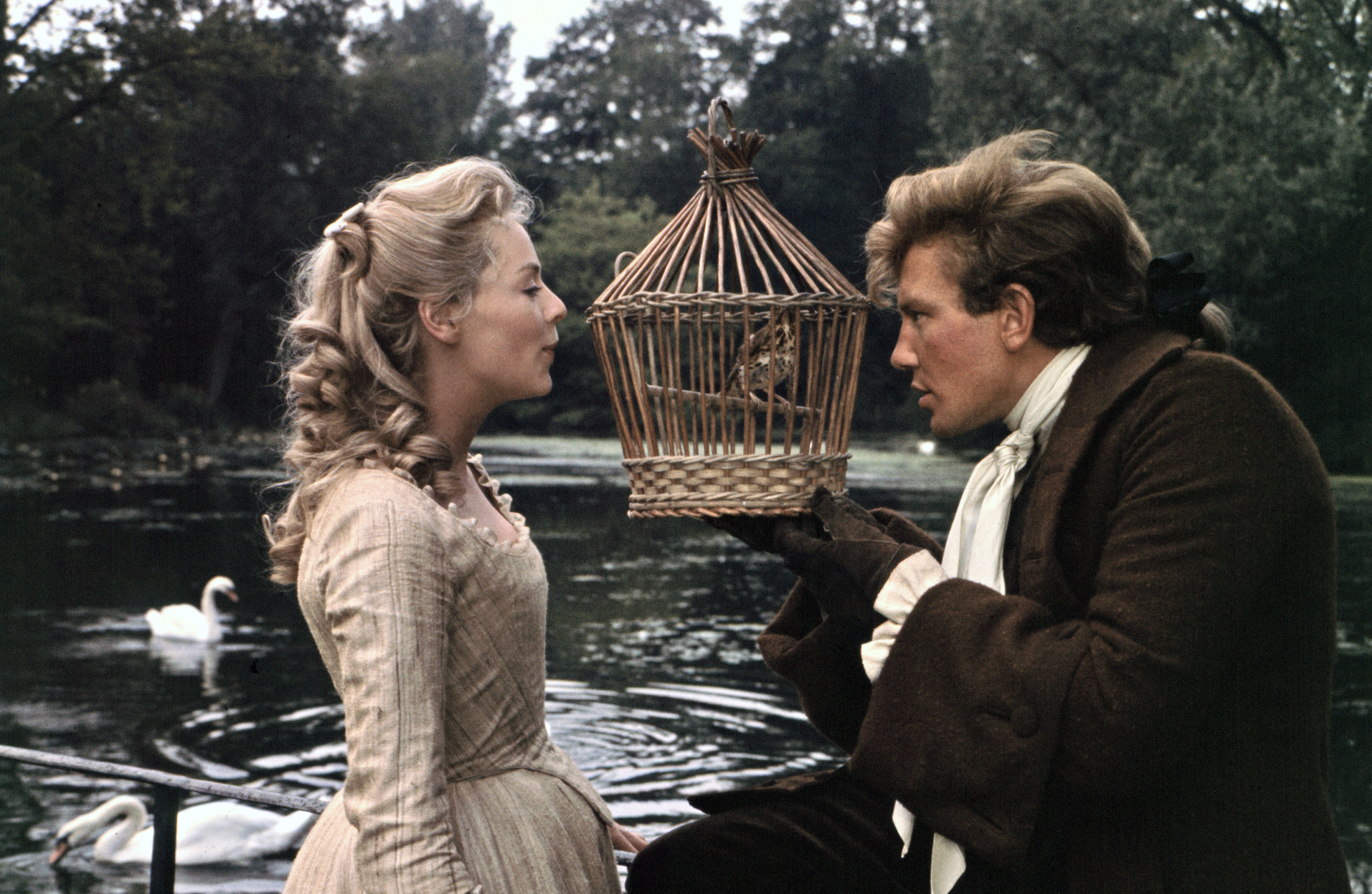

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988)

Whether Terry Gilliam’s mischievous storyteller in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen is a hero, a liar, or both, he is undoubtedly a man who can reach the hearts of those who listen, constructing magnificently surreal worlds of aliens and gods that place him right alongside history’s greatest mythical figures.