Terry Gilliam | 2hr 6min

If Baron Munchausen’s tales of adventuring across oceans, into volcanoes, and through outer space are true, then he may very well belong among the greatest of all heroes. If the flamboyant, swashbuckling explorer is a liar, then he must be the greatest fraud to walk the Earth. If we are to submit to Terry Gilliam’s whimsical view of history and legend as one and the same however, then the difference is entirely negligible. After all, why shouldn’t one of modern Europe’s greatest spinner of yarns stand next to such icons as Odysseus and Heracles, purely based on the awesome wonder that he inspires in the commonfolk?

This is an especially rare talent in the war-torn city of corrupt bureaucrats that the Baron wanders into one Wednesday in the Age of Reason, taking the stage from a theatrical troupe reenacting his grand escapades so that he may correct their inaccuracies. From there, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen transcends the notion of storytelling as mere entertainment, and blurs the boundaries dividing reality and fiction with all the spirited panache of its titular unreliable narrator. So invisible is this margin that is not marked by any sort of cut or dissolve, but simply rather a slick camera movement transitioning from the stage into the ageing voyager’s story, and of course back again when it is complete. With a pair of simple dollies, life and imagination are thus delicately connected through a single line of continuity.

For Terry Gilliam, this playful mythologising is a natural extension of his work in Monty Python, ludicrously undercutting the notion of historical truth by exposing the amusing shortcomings of those who were at its centre. Wordplay, wit, and satire are still very much present in the dialogue, but it is only in this period after the comedy troupe’s breakup that he is also free to explore his magnificent stylistic ambition, formally matching majestic visuals to his farcical storytelling. It certainly helps as well that he is drawing on cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno’s experience shooting some of Federico Fellini and Luchino Visconti’s most extravagantly beautiful films, and using it here to capture a vibrantly expressionistic world steeped in manic surrealism. Together, Gilliam and Rotunno design their frames with an eccentric precision, often using a wide-angle lens to capture odd obstructions, abstract shapes, and staggered blocking of actors within a vast depth of field.

Though the real world is handsomely mounted as a lush framing device, Gilliam’s real visual talents emerge when we enter the Ottoman palace of cocky adventurer’s first tale, cartoonishly patterned with large stripes. There, he wagers his life on a bet that he only barely wins with the help of his magical companions, the super speedy Berthold and uncannily accurate marksman Gustavo. When invited to take his winnings from the Great Sultan’s treasury, strongman Albrecht helps in carrying away its entire contents on his back, while Gustavus wards off the Ottoman army with his powerful breath.

Later, the Baron makes his way into outer space via a hot air balloon made solely out of ladies’ knickers, where he sails across a desert of lunar dust and meets the giant, floating heads of the King and Queen of the Moon. The silvery surfaces present here strike a contrast against the fiery red core of Mt Etna where the Baron encounters Roman god Vulcan, just as they are both visually distinct from the deep blue lighting inside the monstrous sea creature that swallows him whole. According to Gilliam’s design, each new setting is its own world with its own rules, manifesting an imagination so wholly detached from reality that we can only admire the pure invention of it all.

Of course though, neither Gilliam nor the Baron’s tales are quite as wholly original as they might otherwise suggest. The fact aside that The Adventures of Baron Munchausen is loosely based on an 18th century novel, elements of classic fantasy films are woven into its narrative, such as the sea monster from Pinocchio and the hot air balloon escape of The Wizard of Oz. The imprint of Victor Fleming’s Technicolour musical continues to be seen in the one-to-one connections between people the Baron sees in real life and those characters in his stories, many of whom are similarly collected along an unpredictable journey to the outskirts of civilisation and back again.

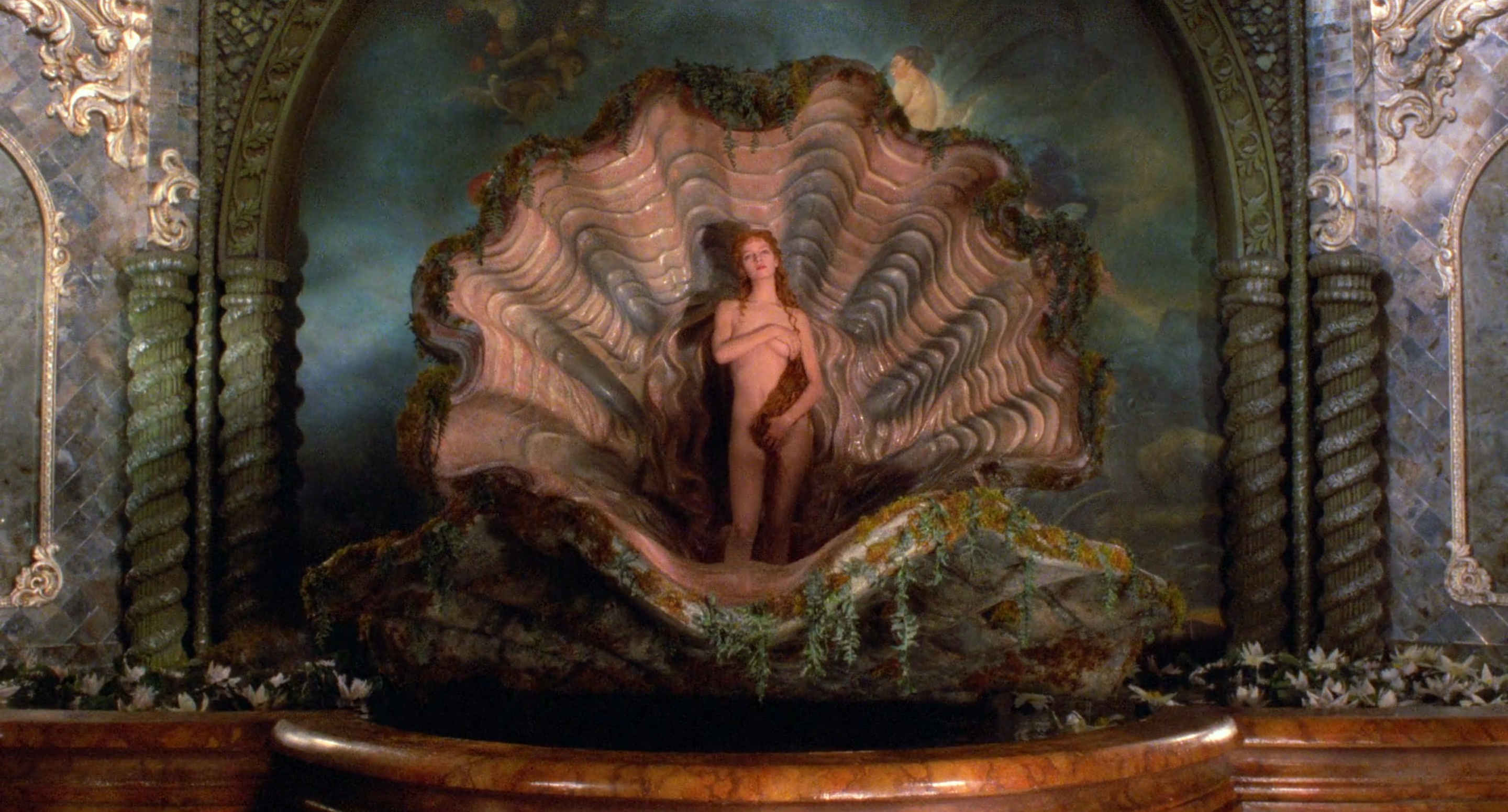

To draw parallels back even further, Renaissance art can be frequently found all through Gilliam’s production design, whether forming stylish backdrops in his elegantly designed interiors or being directly referenced in a recreation of Botticelli’s painting ‘The Birth of Venus.’ Two cupids, the sons of Venus herself, circle her and the Baron as they fly and waltz through a cavern of waterfalls, fountains, and chandeliers, while elsewhere Gilliam’s classical iconography places his protagonist’s legacy among mythical figures and inspires the visual gag of the Baron falling into Vulcan’s lair. As the Baron and his friends lie helpless at the bottom of a pit, a trick of the camera cleverly creates the illusion that Vulcan is a giant, setting up a brilliantly awkward punchline when they enter the same shot and the god’s relatively short stature suddenly comes to light.

The Baron may elderly, but he strikes a robust figure next to monsters and immortals alike, with his long goatee extending as far off his face as his impressive nose. So rejuvenating is the call of adventure for him that it seems to physically erase the wrinkles from his face, and yet he can only keep running away from the Angel of Death for so long. Surreal visions of paradise and mortality are common in Gilliam’s work, whether manifesting in the flying dreams of Brazil or the Red Knight of The Fisher King, and here they become a formal reminder of what awaits those who live such excitingly dangerous lives. Even the Baron’s young companion and frequent rescuer Sally can’t keep it at bay forever, eventually failing to banish the reaper when, just as our hero saves the city from the Great Sultan’s army, he is caught in crosshairs of the mayor’s rifle.

Then again, if there is anything in this quirky cosmos that has the power to resurrect the dead, then it is that very talent which the Baron wields such creative control over. Such is the nature of storytelling that even when it is at its most preposterously absurd, it can influence reality in mysterious ways. Lessons of moderation are learned from aliens who can’t reconcile the division between mind and body, the wrath of a jealous god exposes the insecurity behind great egos, and perhaps there may even be just enough truth in such tales that those living under authoritarian rule can shed the fear keeping them locked away from the world. Whether Gilliam’s mischievous raconteur in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen is a hero, a fraud, or both, he is undeniably a man who can shape the lives of those who listen with open hearts and minds.

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, can be rented or bought Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video, and the DVD or Blu-ray can be bought on Amazon.