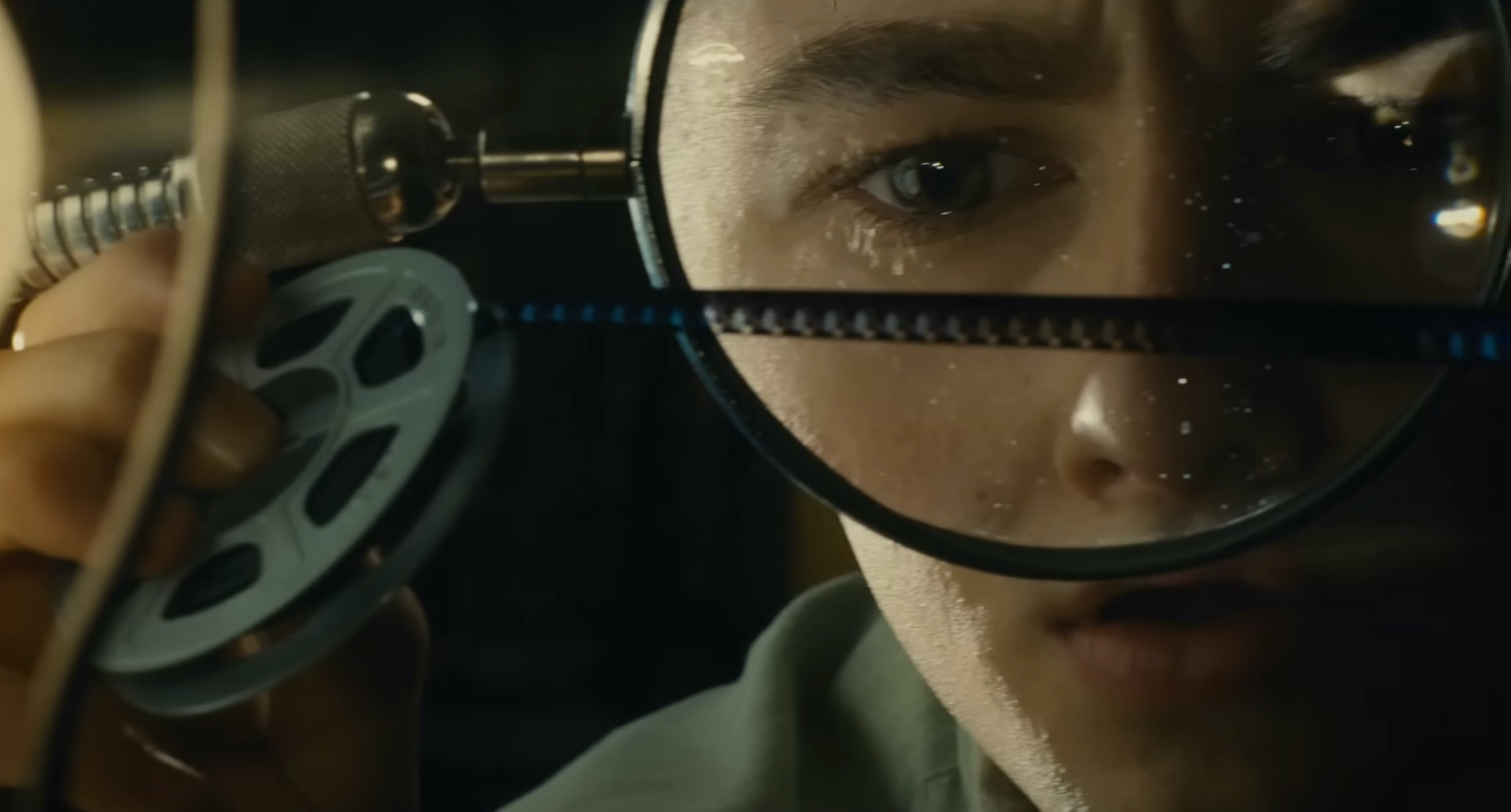

Triangle of Sadness (2022)

Each time we are convinced that the luxury cruise vacation in Triangle of Sadness has hit rock bottom, Ruben Östlund torments his eccentric ensemble of millionaires, influencers, and service workers with yet another horrific development, satirising the extravagant worlds of the ultra-wealthy with a darkly subversive wit and explosively foul set pieces.