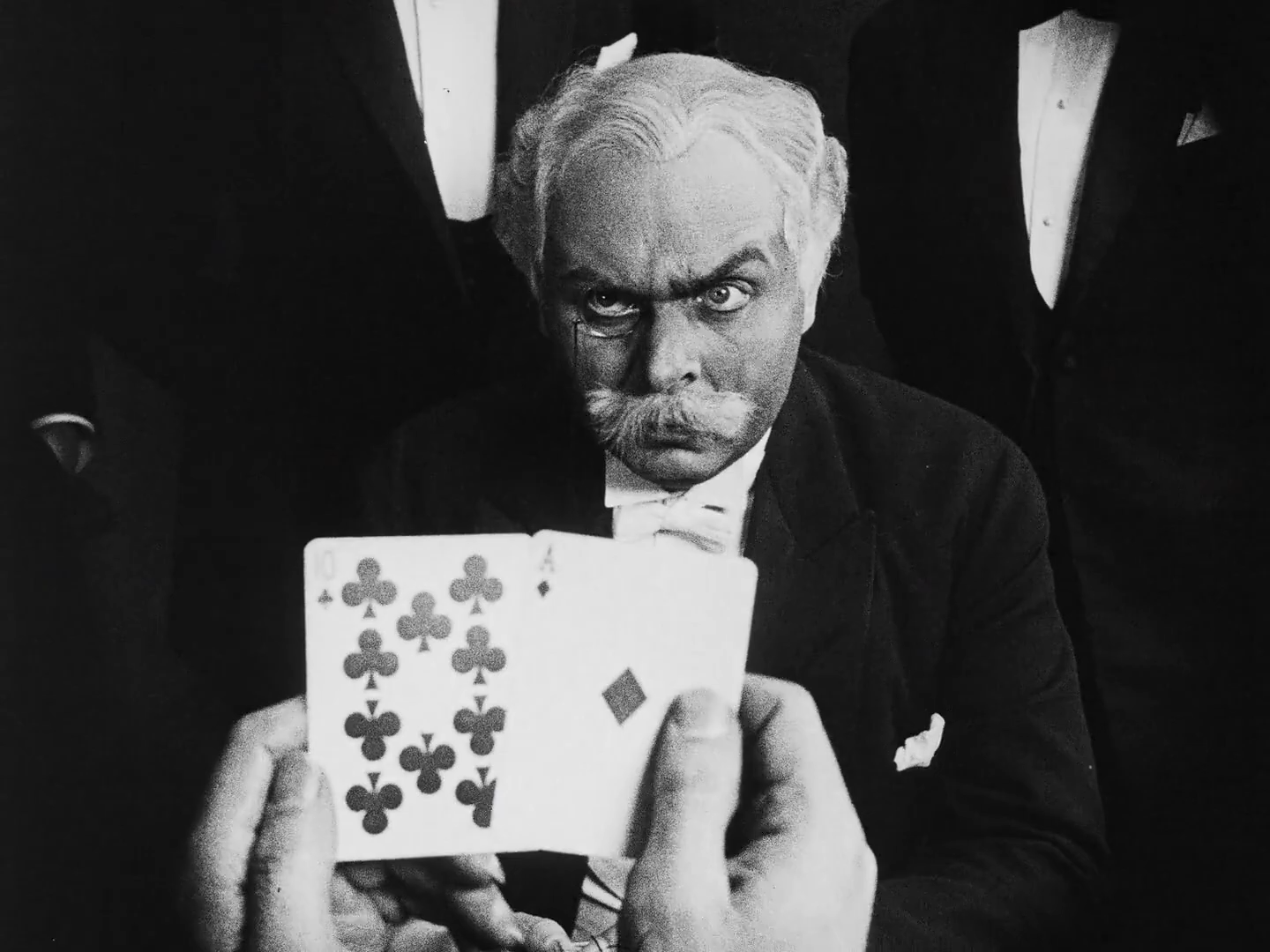

Eraserhead (1977)

Within Eraserhead’s nightmares of mutant babies and urban isolation, it is the psychological impression of its surreal imagery which carries far more impact than any attempts to derive its literal meaning, as David Lynch mystifyingly manifests the dark subconscious of one young father existentially terrified of parenthood.