Deadpool & Wolverine (2024)

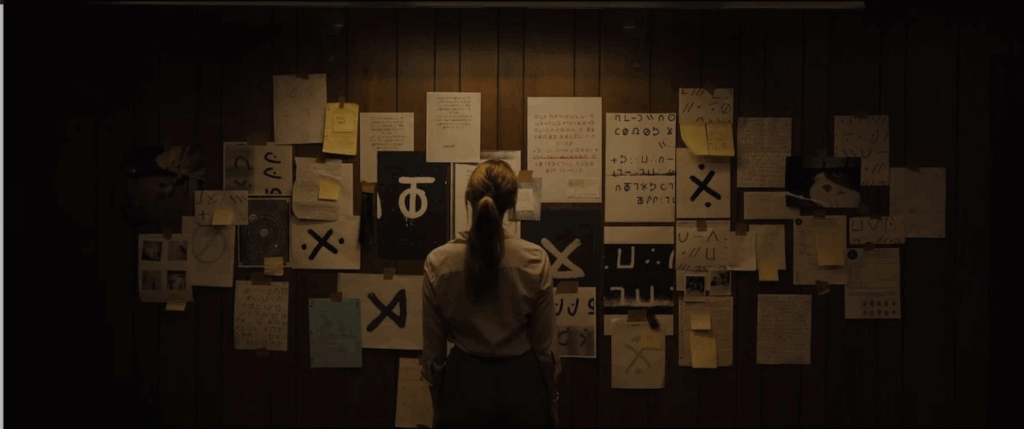

The greatest development that Deadpool and Wolverine has to offer is a surprisingly sincere examination of Logan’s legacy, and yet it is far too caught up in Marvel’s IP to escape its own fourth wall breaking cynicism, jumping between half-baked ideas with all the awkwardness of its disjointed multiverse.