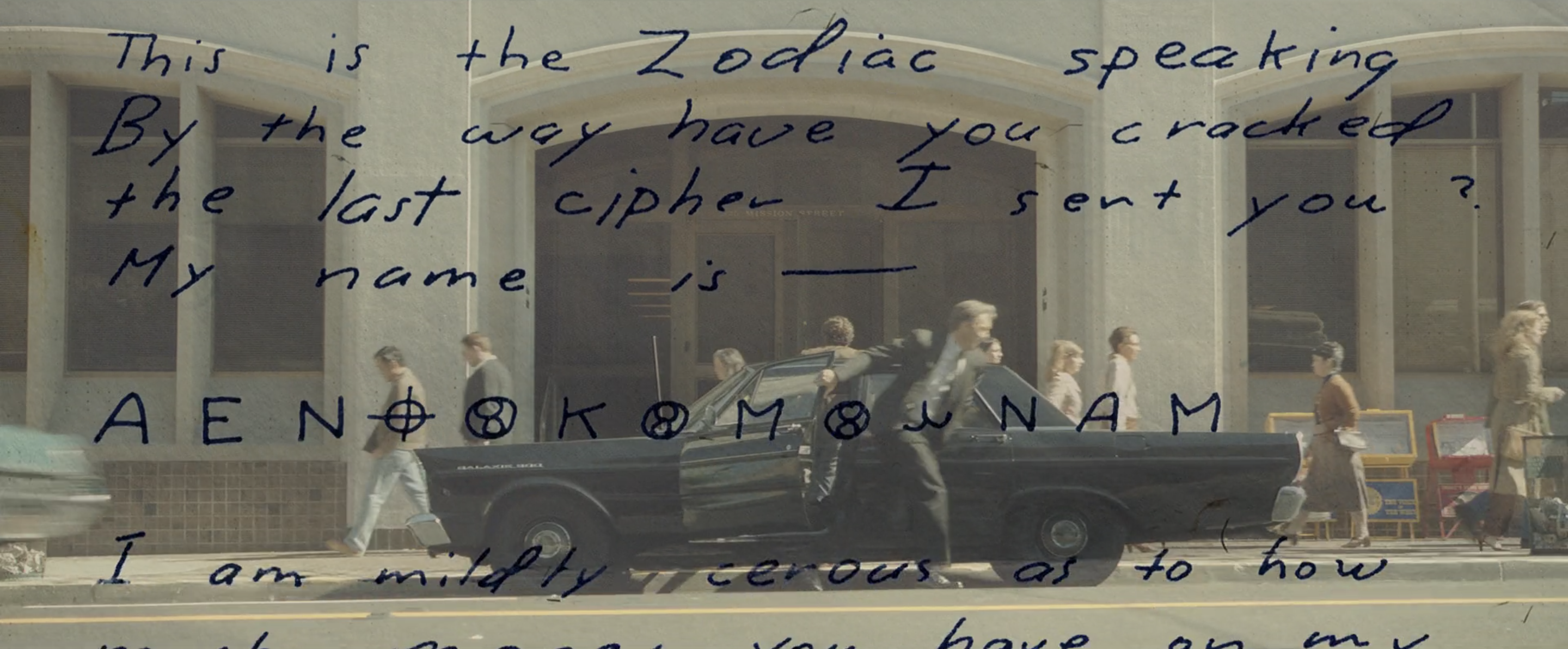

Michael Haneke | 2hr 24min

Michael Haneke continues his use of unsettling, open-ended mysteries to provoke both his characters and viewers into unresolved frustration in The White Ribbon, sending them on a search for answers that never materialise. It is a large ensemble that sprawls out across its bleak, restrained narrative, consisting of largely archetypal figures – most notably the Baron, the Priest, and the Doctor. These men represent wealth, religion, and intelligentsia, and together they enforce strict rules over the women, farmers, and children of the town.

We are first introduced to the narrative by the voiceover of an elderly schoolteacher describing a parable he isn’t sure reflects the truth in every detail, but which he believes may “cast a new light on the goings-on in this country.” The setting is a rural German village on the precipice of World War I. There is no need for any further contextual elaboration from the narrator.

At first the collection of unfortunate, unusual incidents that take place in the town seem like sheer bad luck. Maybe the wire that tripped the Doctor’s horse and sent him to hospital was supposed to be a harmless prank. Maybe the farmer’s wife who fell through rotten floorboards was just being careless. Some events can be more easily explained, like the grieving husband who hangs himself. But still, there is a strange aura of uncertainty around this village that only seems to grow. Suspicion is cast on the children, who exhibit strange behaviour. They leer at grown-ups accusingly, who then in turn deliver cruel, moralistic punishments. One girl seems to possess supernatural premonitions of these events – or perhaps she is really aware of some plot the adults don’t know about.

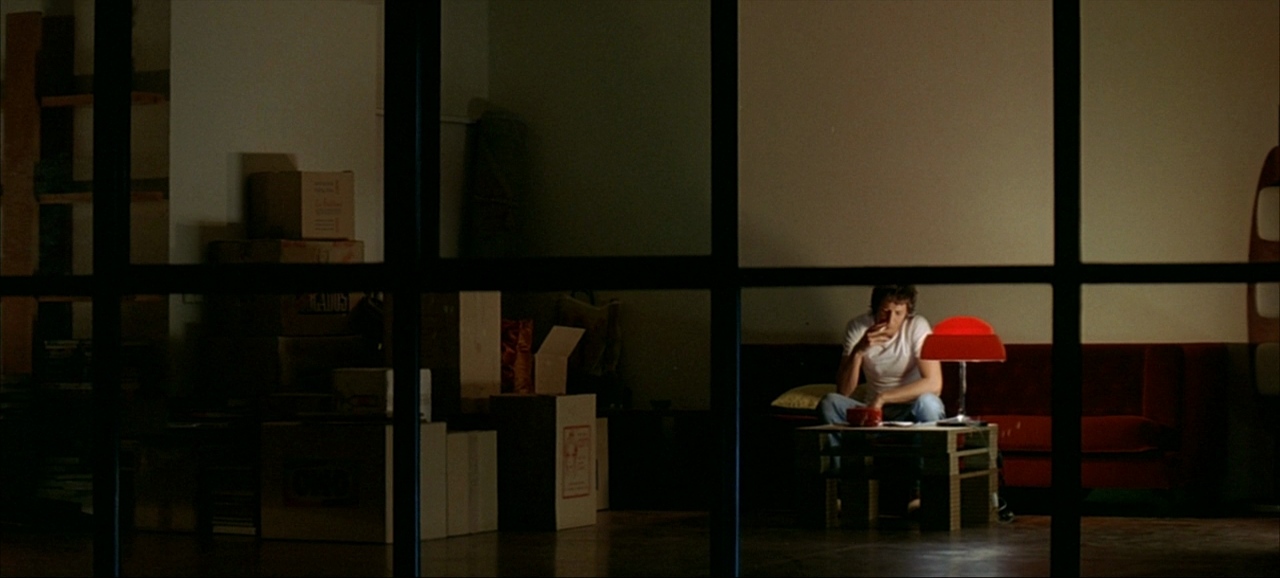

The Priest resolves that tying white ribbons around the arms of the children will remind them of their purity, a fruitless bid for them to remain innocent. Yet these meaningless symbols are at odds with the adults’ treatment of the children. A boy who steals another’s flute is violently beaten by his father. One boy who confesses to masturbating has his arms tied to his bed. Directly after this scene, we catch the Doctor in the act of adultery with the midwife. In truth, it is these men who are the hypocritical, self-righteous sinners of the town. The children’s innocence is under threat from no one but the men who claim they are trying to preserve it.

As the breakout of World War I marks the final act of the film, we are once again reminded of the larger global catastrophe that is mirroring the smaller ones taking place in this town. This war to end all wars was an act of violence by men in positions of power trying to protect their families and countrymen, but it only ended up hurting the innocent. This widespread destruction of innocence traumatised a generation of German youths who would grow up to cause an even greater conflict. Haneke doesn’t offer specific answers about who has been tearing the town apart from within, but he does suggest that these occurrences are a result of the adults’ corruption. A passage from the bible left at the scene of a vicious beating of a child paints this out clearly.

“For I, the Lord, your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sins of their parents’ sins to the third and fourth generation.”

Still, most of the men and women of this town go on in their harsh ways, refusing to accept the possibility that the children are learning cruelty, not discipline.

“Despite the strange events that had haunted the village, we thought of ourselves as united in the belief that life in our community was God’s will, and worth living.”

The few that do recognise the changing behaviours of the children usually go ignored. When the Baroness tells her husband she is taking his children away from these surroundings dominated by “malice, envy, apathy and brutality” and leaving him for another man, his only concern is whether she has slept with this new suitor yet. Later, the midwife learns the truth behind the atrocities, but she quickly disappears. The truth is powerless against whatever is working behind the scenes here. Perhaps we are better off not knowing.

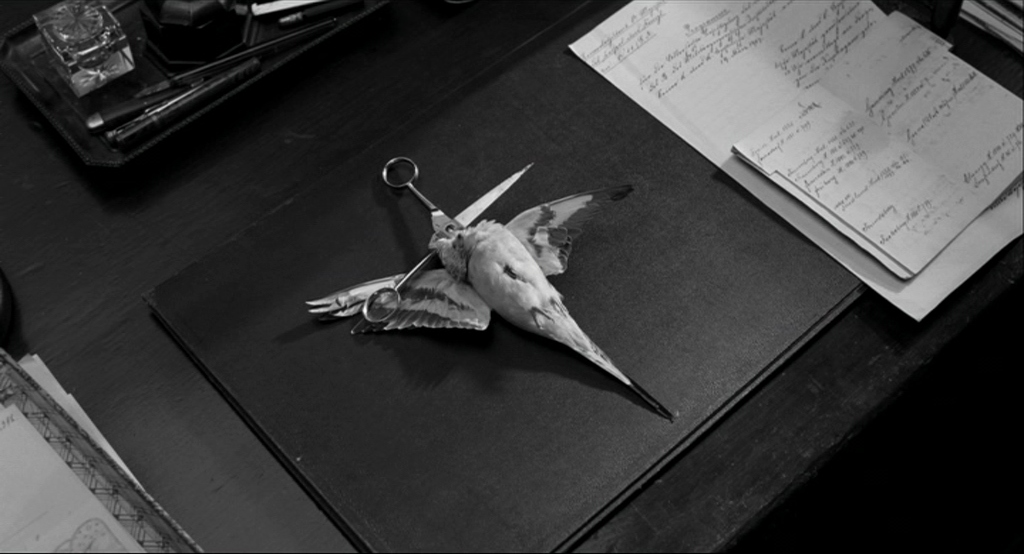

As most of Haneke’s films are, The White Ribbon is formally rigorous in its multitude of motifs. The titular ribbons, the closed doors hiding acts too terrible to see, the parakeets as mirrors of the children’s trauma – Haneke uses symbols to hint at something truly insidious, but just as the film never plunges into the barbarism of World War I, he often leads us up to the doorstep of evil only to cut away at the last second. He keeps us at a distance from his characters. Whenever we do see something horrific, like a mutilated bird or a dead woman, we never get a reaction shot following it. Emotion never immediately spills to the surface, but the cumulative effect of this repression does inevitably burst out in angry, violent demonstrations.

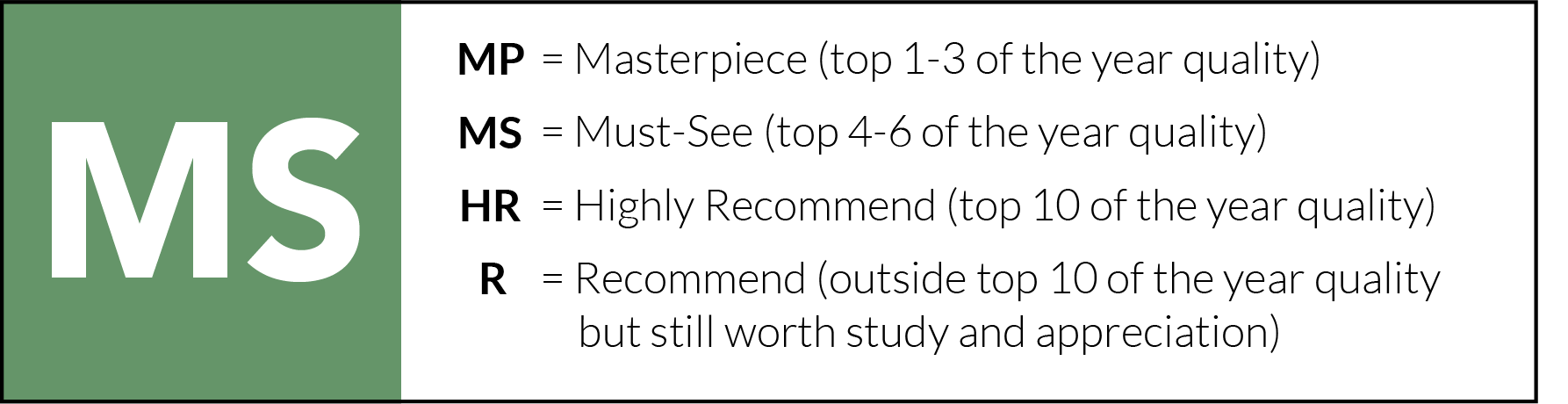

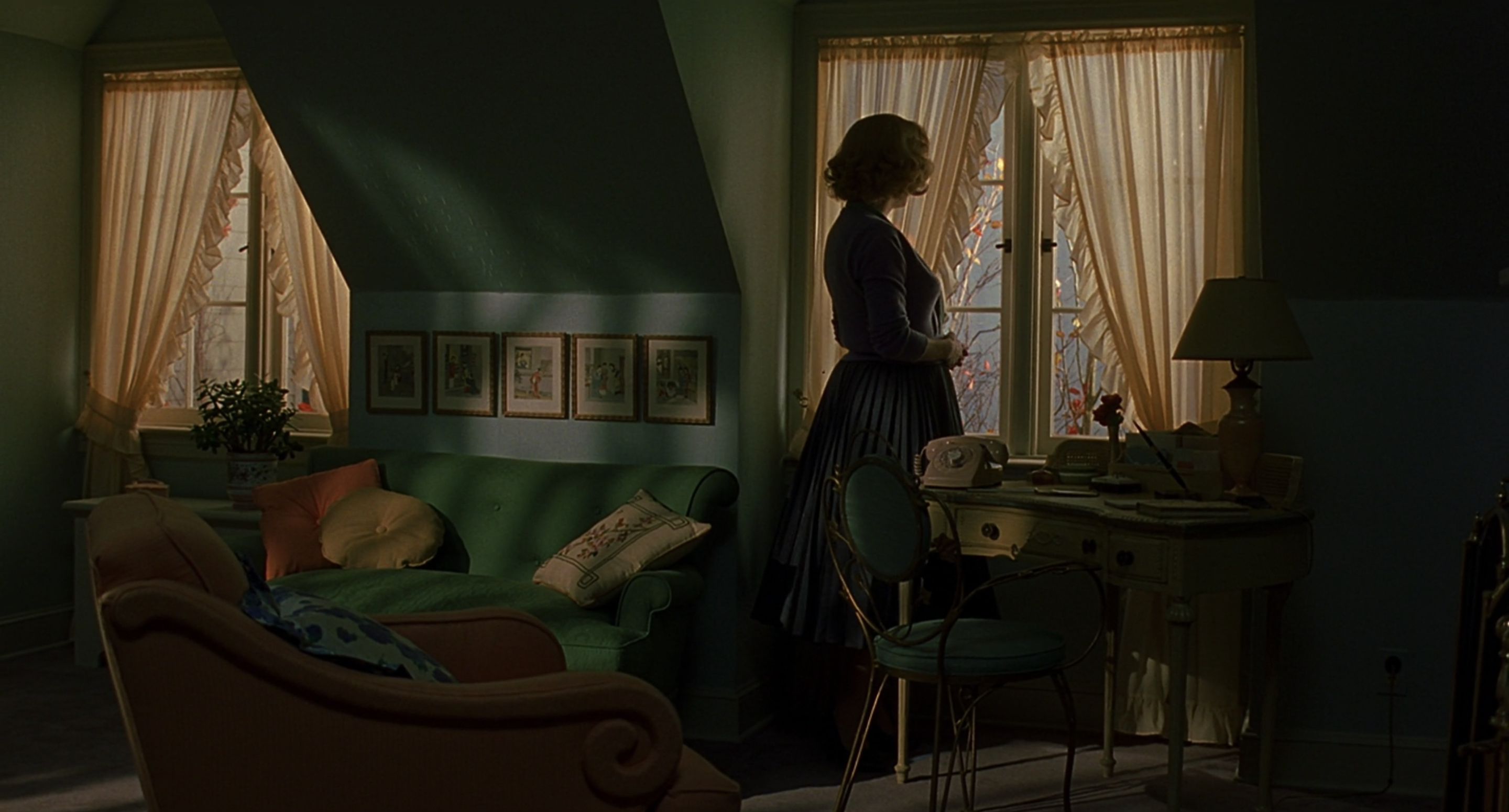

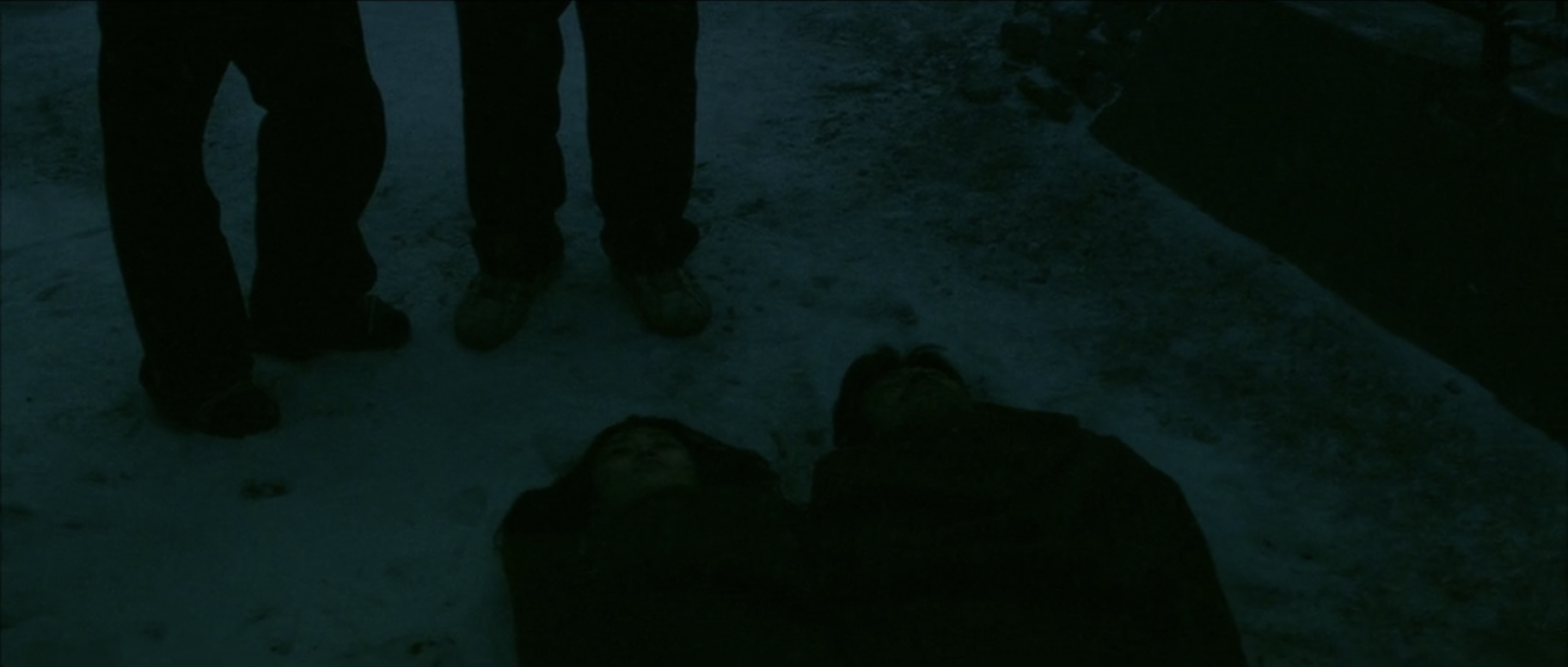

Haneke is not known for his striking images, but the stark, monochrome beauty of The White Ribbon leaps out in practically every shot. Though he isn’t averse to close-ups, Haneke’s wide shots are worth marvelling at for their strong compositions of sharp black and white hues battling it out for dominance of the image. In one scene the darkness of the night smothers the frame, only to be pierced with the blinding light of a fire billowing out from the barn. In another, the narration recalls how the snowy landscape “hurt the eyes”, though dark silhouettes of farmers can still be seen trudging through it. There is detail in the mise-en-scène right down to the costumes, as the opposing shades will clutter tableaus of crowds in the village square, balancing each other out.

Though The White Ribbon is mostly without music, the single exception comes in the final scene set in the church, where the children’s choir sings a hymn. It is an appropriate end to a parable that hints at, without ever explaining, how evil is born through puritanical chastisement, hypocrisy, and apathy. Haneke’s masterpiece is full of tension between the pull of innocence and corruption, but its lack of clear resolution is precisely what continues to make it so compelling.

The White Ribbon is currently available to stream on Beamafilm and Shudder.