Charlie Kaufman | 2hr 4min

For all the times that Charlie Kaufman’s characters cryptically declare that “The end is built into the beginning” in Synecdoche, New York, it wouldn’t be quite right to describe the film’s structure as circular. From the outside it looks far more like a mobius strip, forcing Philip Seymour Hoffman’s pitiful theatre director along paths that invert, double back on themselves, twist inside-out, and lead him back to the lonely, feeble life he has been trying to escape.

If anyone in this absurd universe has any power at all, then it is simply over the journey they will take to their inevitable grave. “It’s a big decision how one prefers to die,” one real estate agent glibly considers while selling a burning house destined to kill its buyer a few decades later, and indeed it may be the only decision that really matter. For Caden Cotard though, that is not enough. To create a piece of theatre that transcends life itself is to effectively become a self-autonomous god of one’s own artificial world, governing the rules of time and fate, and yet this construct is entirely hollow. Death is approaching, hastening with each passing day, and still he remains ignorant to what he believes is little more than a vague concept to be explored through actors and scripts. Kaufman’s mobius strip leads Caden everywhere he desires, only to remind him that he has always been the same sad, mortal being he was at the outset.

It isn’t that Kaufman had been particularly limited by his career as a screenwriter up to this point, but when compared to films like Adaptation and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind it is clear to see just how much he had been itching to disengage his high-concept visions from any familiar reality. The formal ambition on display in Synecdoche, New York’s enormous, postmodern allegory for man’s self-obsessed ego is equal parts staggering and confounding, transporting us into a bizarre Kafkaesque reality that only gradually reveals its underlying insanity. Even in the opening moments depicting a seemingly ordinary morning in Caden’s family home, Kaufman applies an incredible attention to detail whenever the date is mentioned in the mail, newspaper, television, radio, or even on an expired milk bottle, seeing days invisibly slip by despite there being no breaks in the action. For now, Caden’s ignorance to the passage of time is relatively harmless, and yet its relentless acceleration will soon see his six-year-old daughter grow into a teenager in what feels like a few weeks, and years vanish overnight.

Maybe this is why he decides to create a simulacrum of reality within his untitled piece of theatre, funded by the grant he received for his acclaimed staging of Death of a Salesman. Time moves according to his will in this world that has been built entirely around him, allowing him to relive and dissect his past through actors who play out previous real-life scenes verbatim, while he starts and stops the action at his own whim. On one level, he is simply doing this to prove and glorify his intellect, but on another it is a narcissistic self-flagellation, viciously eviscerating himself on a public stage for the sake of his own ego.

“I will have someone play me to delve into the murky, cowardly depths of my lonely, fucked-up being. And he’ll get notes too, and those notes will correspond to the notes I truly receive every day from my god!”

Not that others need his artistic expression to see his flaws for what they are. If anything, he remains blindly ignorant to those insecurities that challenge his masculinity, refusing to confront his repressed homosexuality even as it is noted by multiple other characters, and convincing himself that his psychosomatic illnesses are real. Within the safety of the theatre, he can pick and choose which parts of himself are reflected in his art, making for some amusingly ironic encounters when he forces the self-realisation he is running from on his cast.

“Try to keep in mind that a young person playing Willie Loman thinks he’s only pretending to be at the end of a life full of despair. But the tragedy is that we know that you, the young actor, will end up in this very place of desolation.”

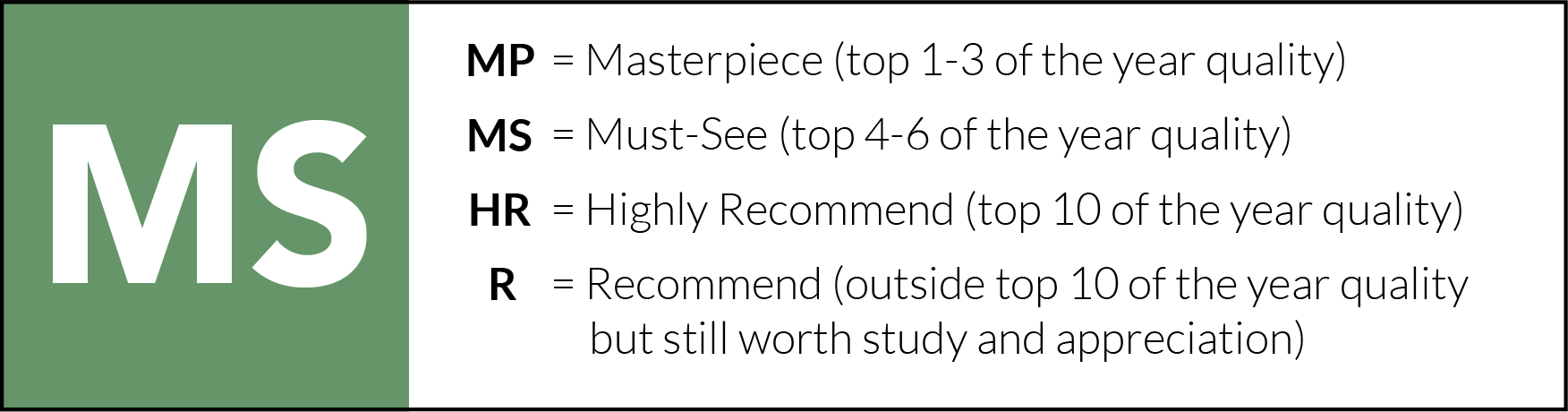

The self-awareness of Synecdoche, New York though continues to go far beyond Caden’s own consciousness – this entire project essentially boils down to Kaufman’s bitter confession of his own creative process, wrestling with his character flaws to create something honest at the expense of others’ time, patience, and sanity. This is nothing new for him, seeing as how he quite literally inserted himself as a character into Adaptation a few years prior, but of all his fictional self-representations Caden cuts the deepest. Part of this has to do with the remarkable formal complexity of his creation, completely blurring the line between reality and fiction as his actors play out seemingly genuine interactions in place of their real-life counterparts, though of course credit must also be given to Hoffman’s tortured, anxiety-ridden performance. Even within the context of his tremendous career, his portrayal of Kaufman’s self-loathing surrogate showcases some of his greatest acting, physically ageing into the body of an old man even as his mind remains stubbornly fixated on his vision of a world preserved in art.

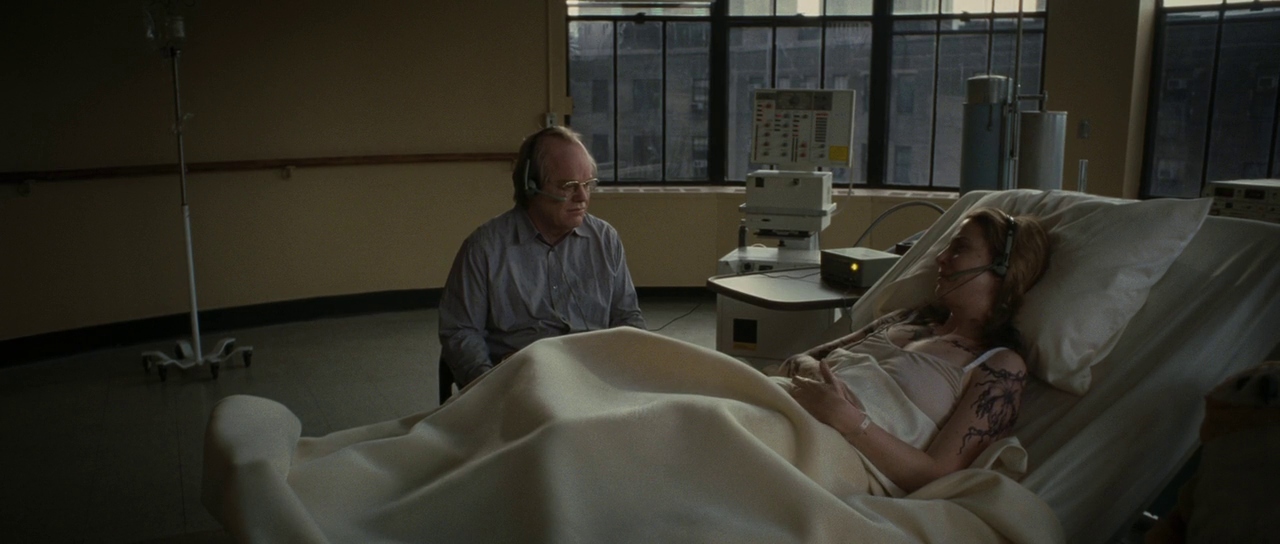

Kaufman’s scathing critique of an artist’s psychology though does not cast as wide a net with its cynical aspersions as one might expect, as while Caden’s sets of streets and buildings continue to sprawl out through his enormous warehouse, his ex-wife’s paintings progressively shrink in size. These creations are every bit the inverse of Caden’s play – tiny, delicate expressions of beauty and humility, not seeking to claim a large plot of real estate in this crowded world, but rather letting its spectators lean in with their magnifying glasses and become active participants in their aesthetic appreciation. This is far more than one could say about Caden’s play, which seems to exist in a permanent state of writing and rehearsal, and refuses to engage with any potential audiences. As far as he is concerned, this work of art serves no one but himself, representing his bloated ego in the expansion of post-it notes across tables and sprawling urban infrastructure through his New York City replica.

If there is anything that distinguishes Synecdoche, New York as the product of a screenwriter making their foray into film direction, then it is the fact that Kaufman’s achievement primarily lies in the intelligent formal construction of such an intricately absurd meta-reality, while neglecting the development of any binding aesthetic. Unlike his later work in I’m Thinking of Ending Things, his visual invention here never quite matches the peculiar world he has created until its final scenes, where Caden shrinks against a giant, grey city, and the limits of his ambition are confined under an industrial ceiling where one might expect to find a boundless sky.

Decades continue to slip by in this space and Caden becomes an old man, yet it still barely matters to him that the real world outside has crumbled into apocalyptic dystopia, even as its corruptive influences infiltrate the dreary fantasy he has made his home. As one of its few remaining survivors, he wanders its bleak urban wasteland littered with burning cars and dead bodies, still delving layers deeper into his lonely existence – not as a vain, power-hungry director, but as an actor to be manipulated by another director superseding him. More specifically, he takes on the role of Ellen, his daughter’s custodian, while the actress who played her becomes his god, speaking directly into his mind. For what seems like the first time in Synecdoche, New York, Caden’s inner monologue is not just filled with regret for his own wasted time, but empathy for the misery of others.

“What was once before you – an exciting, mysterious future – is now behind you. Lived, understood, disappointing. You realize you are not special. You have struggled into existence, and are now slipping silently out of it. This is everyone’s experience. Every single one. The specifics hardly matter. Everyone’s everyone. So you are Adele, Hazel, Claire, Olive. You are Ellen. All her meagre sadnesses are yours. All her loneliness. The grey, straw-like hair, her red raw hands. It’s yours. It is time for you to understand this.”

Caden’s anguish is not unique, and never has been. His is the story of every human to have ever lived, following a path back to the state of non-existence which preceded their birth, and yet for some arrogant reason he has convinced himself that he is the orchestrator of his own fate. In his final seconds, as he considers what might as well be the hundredth potential title for his play, the voice of his indifferent god who continues to direct him right to the end cuts him off with a short, sharp instruction. There is little more to be said about his sad, solitary existence when that word is uttered, finally dooming him to the obscurity that he spent his entire life running from.

“Die.”

Synecdoche, New York is currently available to rent or buy on Google Play and YouTube.