Peter Jackson | 3 parts (3hr 28min – 4hr 11min)

With The Lord of the Rings dominating so much of 21st century pop culture, it is easy to take for granted just how subversive J.R.R. Tolkien’s story was in the 1950s, even as he borrowed pieces of Greek, Nordic, and Germanic mythology. Our central hero is not some predestined Chosen One like Achilles, a legendary wizard such as Merlin, and does not possess the extraordinary physical strength of Beowulf, though these ancient archetypes certainly populate the narrative’s sidelines. Should any of these alternate characters attempt to fulfil the main quest at hand, they would be guaranteed almost certain failure. Humility and loyalty are far more important qualities here, neither of which are so easily corrupted by the One Ring that reaches into the minds of those with altruistic ambitions and twists them into selfish megalomaniacs.

As a result, Frodo Baggins the hobbit stands among the few figures uniquely capable of carrying and destroying this cursed artefact, and is consequently driven to separate himself from his Fellowship of powerful companions who may fall to its temptation. The Lord of the Rings stretches across an enormous span of land and time, yet by framing this ordinary creature who has never stepped far outside his home as our primary protagonist, Tolkien offers a fresh perspective that Peter Jackson gladly capitalises on in his cinematic adaptation.

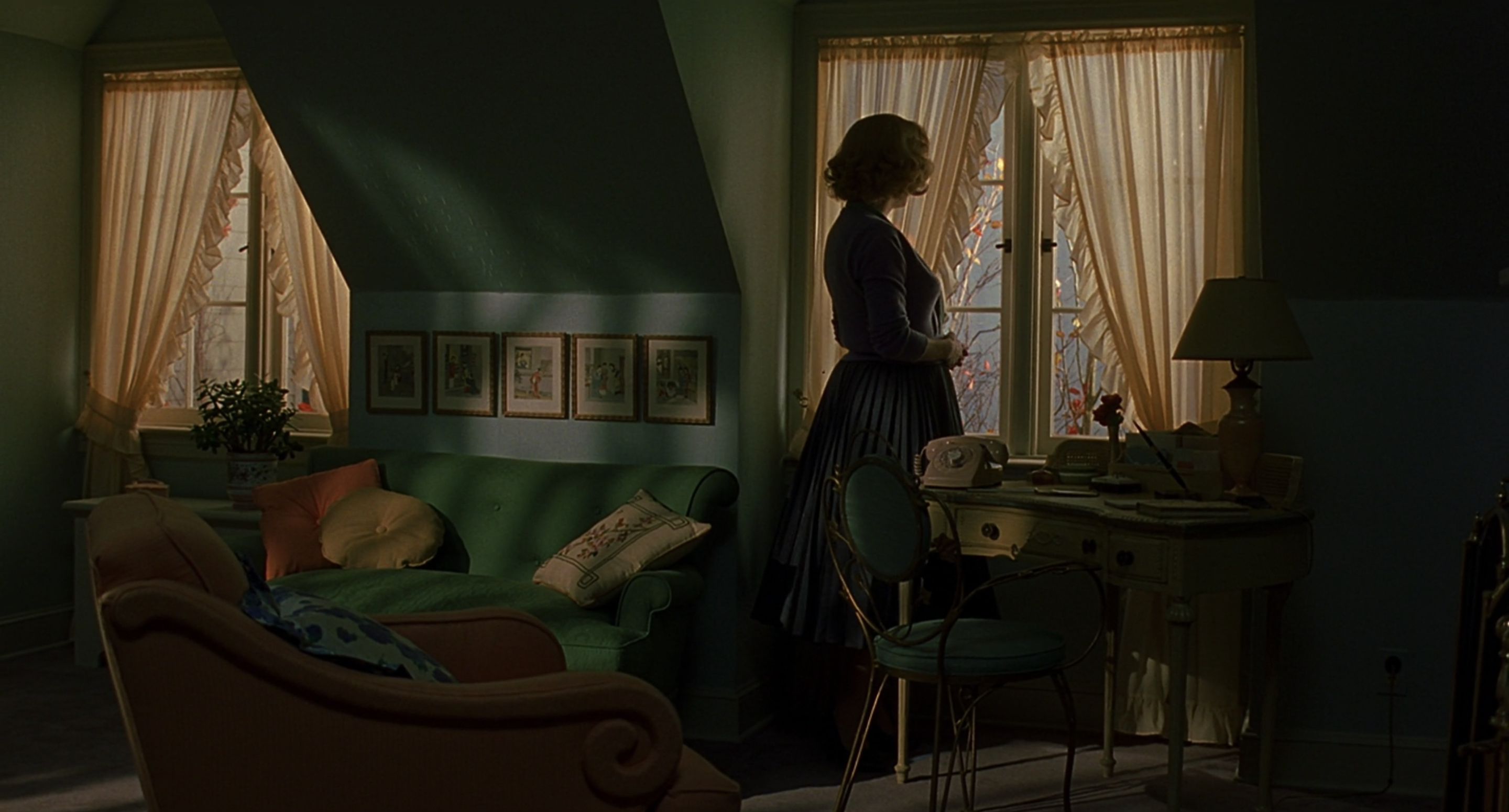

Through Frodo’s inexperienced eyes, we appreciate Middle Earth as one of the richest fictional worlds of literary history, complete with fully developed languages, genealogies, and cultures. While this film trilogy only touches on a small portion of Tolkien’s original creation, there is a wonder here that emerges from Jackson’s rendering of its extraordinary, almost imperceptible details. With enormous respect to the astonishing work of literature that had been placed in his hands, Jackson went about faithfully translating the written descriptions of great civilisations, creatures, and weapons to a visual medium, imbuing the design of each with a level of cultural and historical detail that takes multiple viewings to properly comprehend. Jackson realises that we do not need close-ups on the runes of Orc armour nor the embroidered textures of an Elven mourning dress to note their significance. Simply by including them in the frame, he viscerally conveys the sprawling authenticity of his intricately constructed world with minimal exposition, while occasionally compromising on the compositional beauty they may have offered with more precise framing.

A huge portion of this fantastical visual style of course comes down to his fine synthesis of digital and practical effects too, more frequently relying on the latter with his matte paintings and miniature city models built into the side of imposing mountain ranges. Along with deserved comparisons to D.W. Griffith’s historical standard of epic filmmaking, Jackson makes a name for himself next to Georges Méliès with his in-camera illusions, shrinking hobbits and dwarves next to taller creatures with forced perspective angles. Meanwhile, CGI is judiciously used to elevate these practical effects rather than replace them, allowing an expressive motion-captured performance from Andy Serkis as Gollum that may have otherwise been limited beneath layers of prosthetics. As evidenced a decade later with The Hobbit trilogy, technological innovation does not equal art, but much like James Cameron and Christopher Nolan at their peaks, Jackson is primarily using it here as a tool for his grand storytelling and world-building.

Even with all that stripped away though, there is no doubt to be had regarding the raw power of Tolkien’s narrative. In this epic battle between good and evil, there is a very simple objective uniting the Free Peoples of Middle Earth against Sauron, though it is often the smaller battles and personal motives which give a complex weight to this twelve-hour saga. The ensemble is huge, but the nuances of every relationship are worth savouring, from Aragorn’s love for the immortal Arwen, to Gandalf’s grandfatherly affection towards the hobbits. Even on repeat viewings, it still lands as a shock that his death takes place so early, foreshadowing the inevitable breaking of the Fellowship that splits the story into further subplots and develops individual characters through their isolation.

Where Tolkien’s novels segmented each of these plotlines into individual parts, Jackson propels his narrative forward with brisk parallel editing, drawing heavily on the foundational rules of film language that D.W. Griffith developed in its earliest days. Much like the father of modern cinema, Jackson is both an artist and technician of staggeringly large set pieces, skilfully establishing the geography of fortresses and battlefields in sweeping long shots before cutting between the smaller conflicts within them. The orcs’ assault of Helm’s Deep with siege ladders and catapults is especially reminiscent of the fall of Babylon in Intolerance, while through the chaos Jackson continues tracing the movements of each key player, alleviating the tension with some friendly competition between Legolas and Gimli.

Beyond the action as well, Jackson goes on to prove his mastery of epic visuals in the helicopter shots flying over New Zealand’s sprawling mountain ranges, while those static compositions overlooking lush panoramas and ancient cities often look like paintings in their spectacular beauty. Much like Griffith, there is also immense power in his expressive close-ups, framing Arwen like a stone statue beneath her mourning veil and teetering Frodo on the brink of obsessive madness at the Cracks of Doom.

This balance between the epic and the intimate is the foundation of not only The Lord of the Rings’ tremendous narrative, but also its core belief in the mighty influence of the tiniest creatures. This extends past our four central hobbits, as Gandalf wisely notes that Gollum may play a crucial part in determining the fate of Middle Earth too. This is true on two levels – not only is he incidentally responsible for the destruction of the One Ring at Mount Doom, but to Frodo he also serves as a reminder of the disaster in store should he similarly fall to its temptation. The two opposed voices that split Gollum right down the middle manifest as entirely different beings in Jackson’s editing, alternating the camera position between his left and right sides while they argue, and thereby revealing the quiet, fragile innocence that persists in the mind of this corrupted being. Though Frodo recognises how easily his sympathy for Gollum might be manipulated, he still hangs onto it as a tiny shred of hope for his own redemption.

“I have to believe he can come back.”

While Frodo, Sam, and Gollum are continuing their uphill struggle, Tolkien’s ‘David and Goliath’ metaphor also sees Merry ride into the Battle for Middle Earth and deliver a crippling blow to the Witch King, Pip save Faramir from certain death, and both spur the peaceful race of Ents to action through their words alone. Because of them, the forests of Middle Earth rise against the armies of the white wizard Saruman, recalling the primordial imagery of the Battle of Dunsinane from Macbeth. Not content that nature’s vengeance in Shakespeare’s play was merely an illusion though, Tolkien manifests it on a literal level in The Lord of the Rings, pitting the tree-like Ents against the Uruk-hai orcs that Jackson associates with modern forces of technology, industry, and the careless obliteration of life.

It takes more than just the fury of the natural world to save Middle Earth from Sauron’s terrible reign though, but also a righteous spiritual grace. Between our heroes of Gandalf, Aragorn, and Frodo, Tolkien essentially splits his Messiah into a trinity, each taking on key characteristics of Christ. After being constantly underestimated as a friend to the meek and lowly, Gandalf is resurrected with new powers, saving Theodon from his brainwashed servitude and vanquishing foes with a dazzling white light. By setting the souls of the suffering free, Aragorn saves Middle Earth from devastation and reigns as its new King, bringing in an age of peace and prosperity. Finally, left to carry the sins of the world around his neck, Frodo offers up the greatest sacrifice of them all, and heads towards what he can only assume will be certain death.

There is no doubt that Jackson recognises the biblical connotations of the flood washing away Saruman’s forces at Isengard too, or the original sin committed by Isildur that led to the fall of man, though he never underscores this theological symbolism so blatantly. These narrative archetypes largely speak for themselves, emerging organically in Jackson’s storytelling that finds new visual expressions for Tolkien’s mythology, and which continues to build on its classical influences through Howard Shore’s operatic film score. Just as Tolkien drew significant inspiration from the 19th century cycle of epic music dramas Der Ring des Nibelungen, so too does Shore borrow many of Richard Wagner’s classical instrumentations and techniques from that work, developing a rich assortment of leitmotifs that evolve with the narrative.

The very first of these we hear in the prologue is the Ring theme, played by a thin, double-reeded rhaita that slyly rises and falls along a harmonic minor scale, while Cate Blanchett’s deep, resonant voiceover informs us of its dark history. Because of this uneasy opening, we welcome the shift to the warm, sunny Shire with delight, and embrace the new motif led by a folksy tin whistle that, from this point on, will always remind us of home. Later when Frodo reunites with his uncle Bilbo at Rivendell, it matures with the elegant timbre of a clarinet, before breaking into destitute fragments when a partially corrupted Frodo pushes Sam away late in their quest. When the four hobbits do finally return to the Shire at the end of this colossal journey, the melody is mostly restored in its original form, and yet the flute which now takes over marks a melancholy evolution that keeps these four hobbits from recovering their lost innocence.

Shore’s music continues to reach even deeper into Middle Earth’s mythology as well, using Tolkien’s constructed languages in choral arrangements as the Fellowship descends into the dwarven Mines of Moria, and as they enter the elven woodland realm of Lothlórien. So too does it serve a crucial role in connecting these characters to their respective cultures and legends, transposing poems from the books into diegetic songs sung by characters in moments of celebration and reflection, most notably in Pippin’s lyrical lament ‘The Edge of Night’. As his soft voices echoes through the cavernous halls of Gondor, Jackson reverberates it across a devastating montage of Faramir and his men riding towards their massacre, intercut with his cowardly father vulgarly ripping into a meal that drips blood-red juices down his chin.

“Home is behind,

The world ahead,

And there are many paths to tread,

Through shadow,

To the edge of night,

Until the stars are all alight,

Mist and shadow,

Cloud and shade,

All shall fade,

All shall fade.”

Even on a structural level, Shore integrates the mystical numerology of Middle Earth into his rhythms and notations, particularly using the number 9. There were nine rings created for Men, and nine heroes tasked with carrying the One Ring to Mordor, and so the musical leitmotif used in the themes for both the One Ring and the Fellowship are similarly composed of nine distinct notes. Somewhat poetically, that number also binds together the fates of Sauron and Frodo, with both eventually losing the Ring by having a finger severed and leaving them with only nine.

It is in this repetition of history that The Lord of the Rings unfolds its second great subversion of the archetypal quest narrative – even after an immense journey across Middle Earth that has seen many give up their lives, our hero fails his mission. As Frodo turns to Sam atop the Cracks of Doom and chillingly claims the Ring as his own, he strikes a mirror image of Isildur doing the exact same many millennia before, finally falling to its corruptive influence. It would appear that no living entity can destroy Sauron, no matter how large or small they may be. There is only one force powerful enough to defeat an evil this powerful, and that is the evil itself, incidentally turning two of its own corrupted beings against each other in a jealous struggle and thereby sending the Ring plummeting into the lava from which it was forged. Should those who fight for all that is right fail in their mission, Tolkien is resoundingly optimistic that wickedness will collapse under its own unsustainable power.

Like his fellow hobbits, Gollum’s purpose has been found, though there is no path to redemption for him as there is for Frodo. Jackson’s ending to the final film in The Lord of the Rings trilogy has often been accused of long-windedness, though such an expansive story necessitates a conclusion with weight and patience behind it. Even with Sauron defeated, Frodo’s arc is not yet complete, and continues to draw him towards a peaceful resolution in the Undying Lands with Gandalf, Bilbo, and the Elves. How fitting that Tolkien imagined the future of Middle Earth as our present reality where magic has died out and Men have lived on, because at the end of all things, Jackson’s fantasy epic stands as a monumental tribute to their greatest qualities of ambition, endurance, and pure, ingenious creativity.

The Lord of the Rings is currently streaming on Netflix, Prime Video, Binge, and Paramount Plus, can be rented or bought on Apple TV, Amazon Video, or Google Play, and the Blu-ray or DVD can be bought on Amazon.