Roy Andersson | 1hr 40min

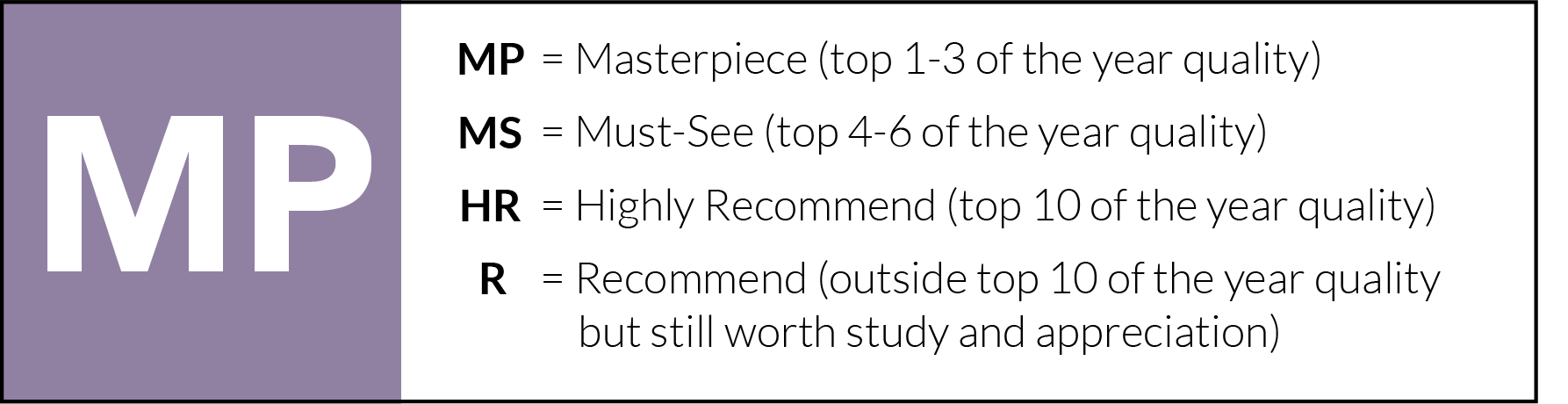

Somewhere in the unnamed Swedish city of Songs from the Second Floor, a crash test dummy falls seemingly out of nowhere into a quarry. In a lavish hall, a crowd of clerics, aristocrats, generals, and businessmen prepare a young girl called Anna for a mysterious task. Finally, Roy Andersson pays off both scenes in a darkly funny punchline that leads the child along the top of a cliff, before sending her plummeting to an unseen death. As the same elites who groomed her for this ritual passively bear witness, a mournful hymn builds to a crescendo, commemorating the innocent life they have sacrificed to whatever gods might save them from the insipid, desolate hell they themselves have built on Earth.

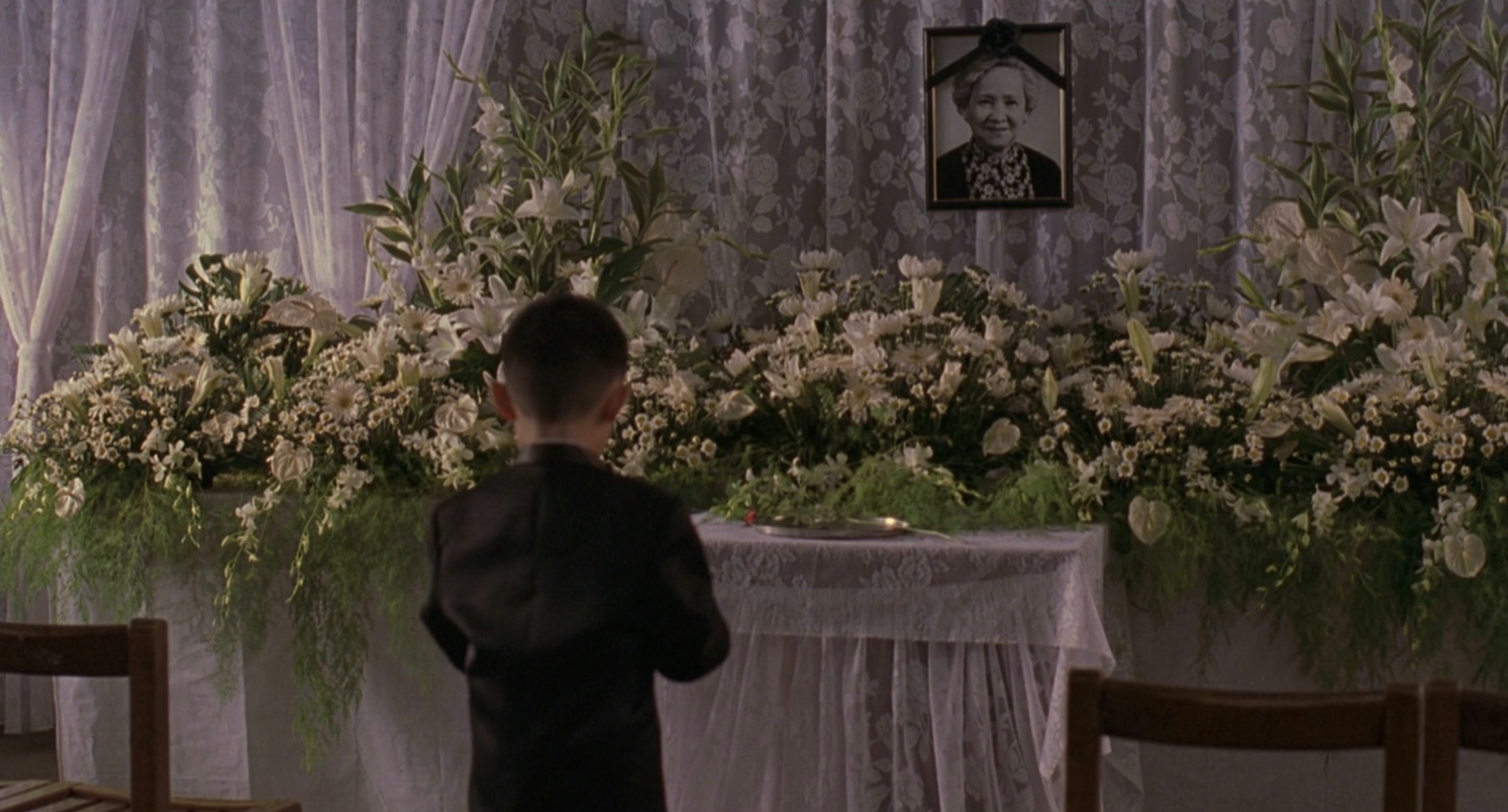

Like an artist curating a solo exhibition, Roy Andersson is compiling a gallery of evocative tableaux that each express their own self-contained story in Songs from the Second Floor. No single image here reveals the full apocalyptic senselessness that this city of eternal traffic jams and mind-numbing bureaucracy has descended into, but when each are considered in unison, a more expansive landscape begins to form of surreal, urban decay. There is no redemption for bosses who fire their most loyal staff after 30 years of service, and no hope for the employee who pathetically clings to his superior’s leg as he is dragged crying down office hallways. All that can be done is to bury the shame deep down – though where is the sanity in that when humanity’s moral failures pervade the mundanity of everyday life?

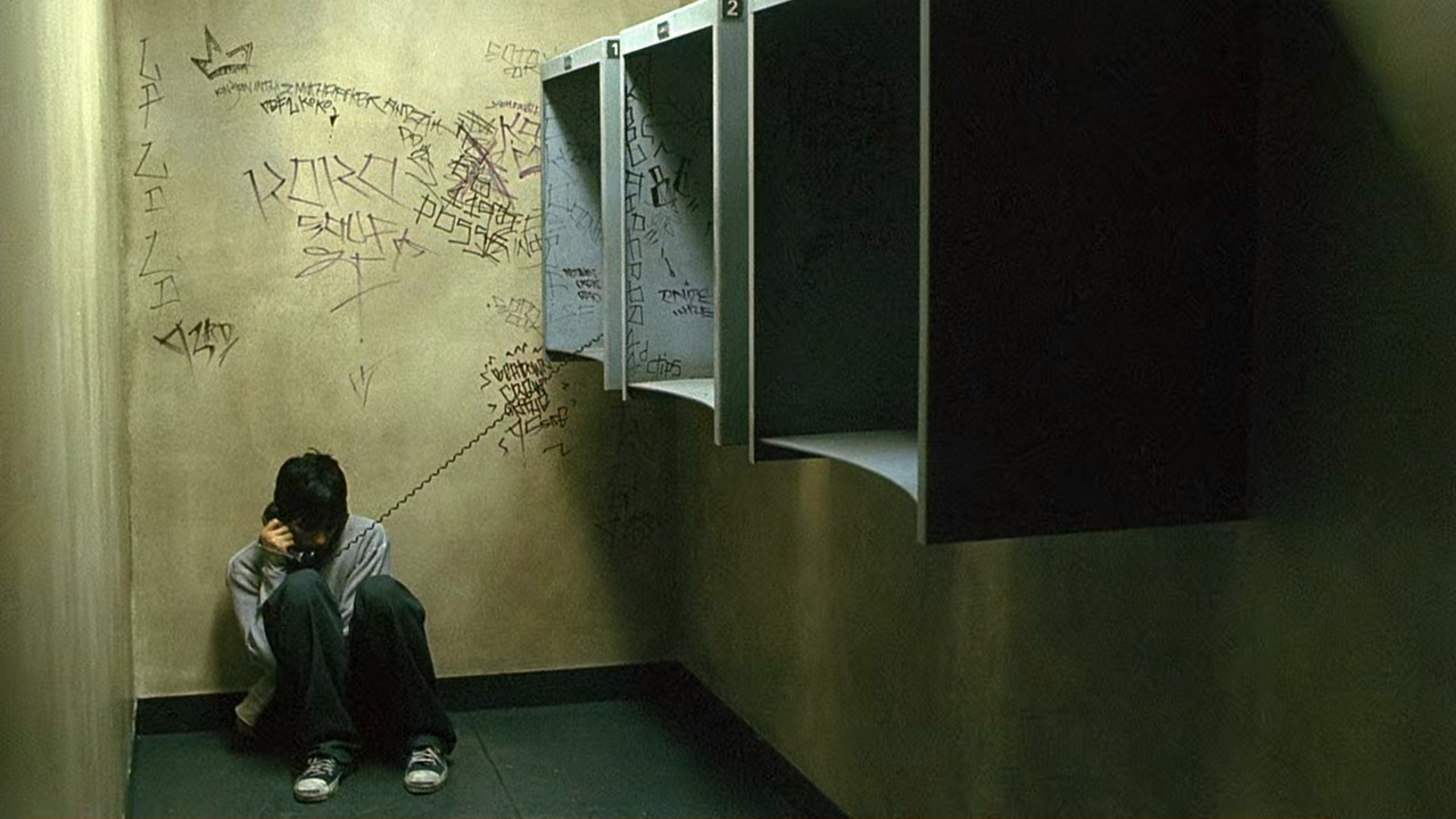

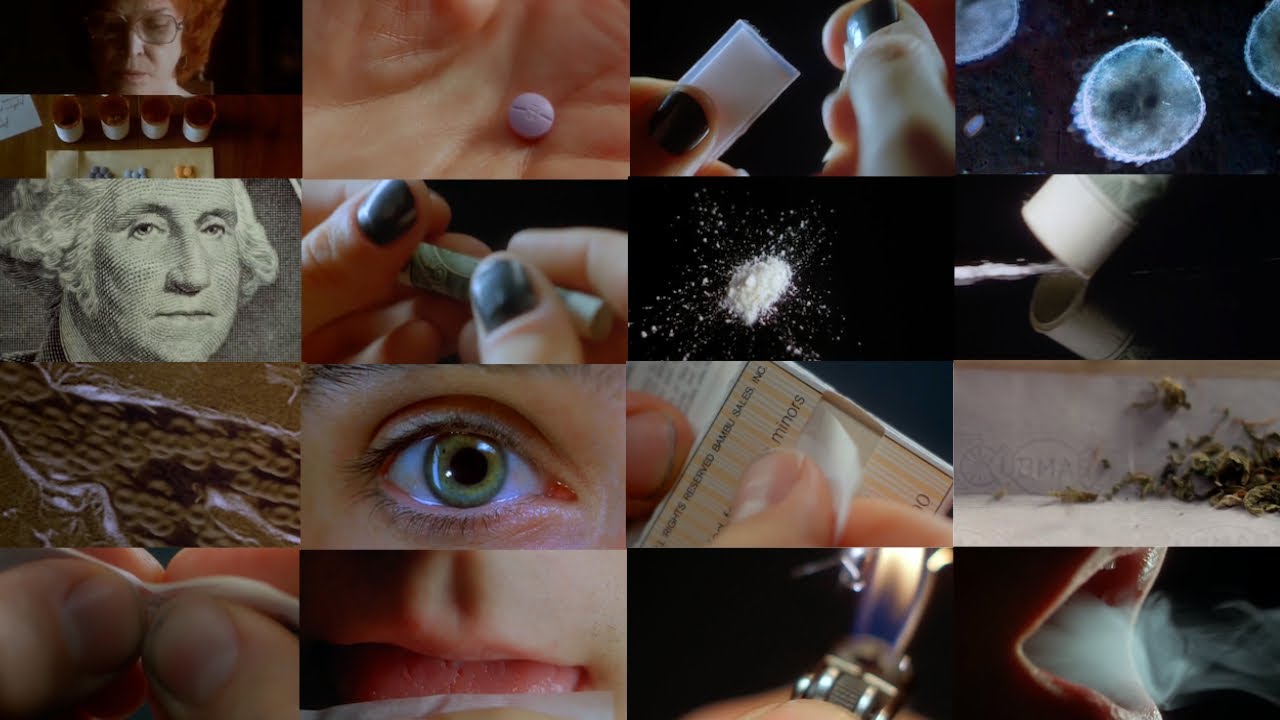

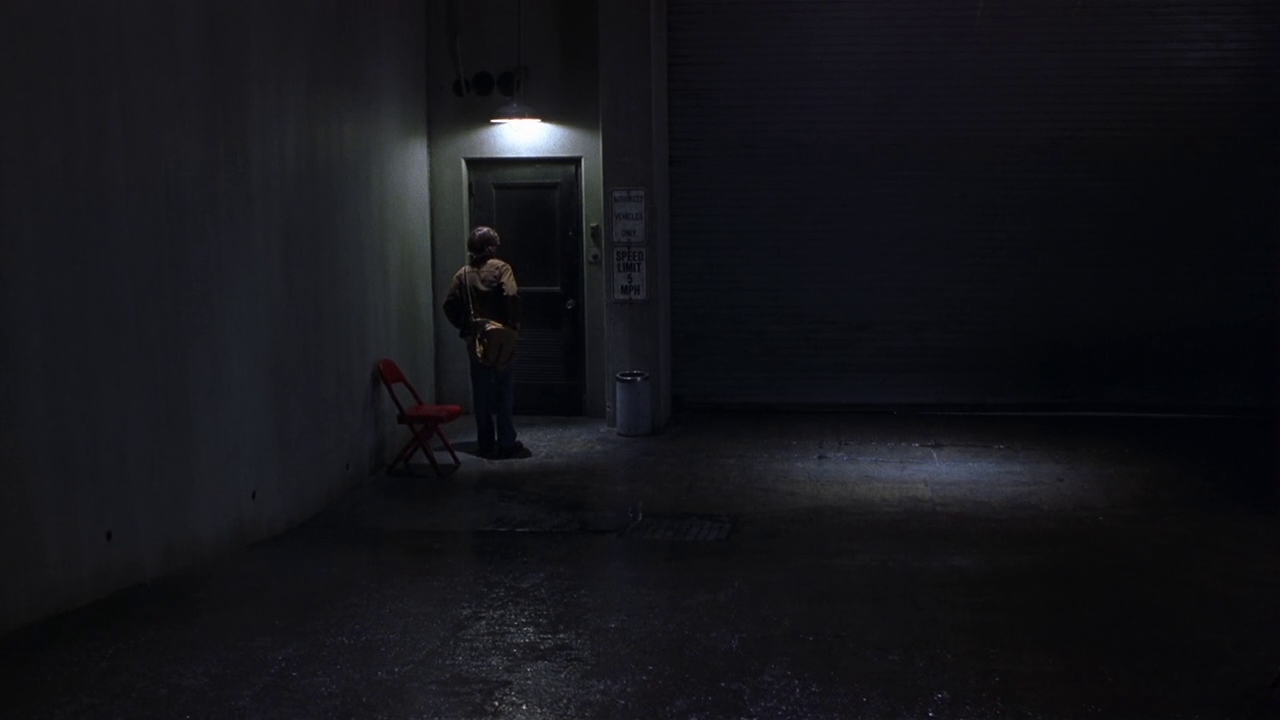

Individual scenes here vary between tightly interwoven episodes and standalone vignettes, yet each play their role in Andersson’s astoundingly formal world building, erecting life-sized dioramas that trap pale, lethargic characters in Edward Hopper-style paintings. There is a complete absence of in-scene editing, and in its place we find a consistent dedication to wide, static shots with a remarkable depth of field, often extending highly stylised sets far into the distance where background figures carry out their day-to-day routines. At its most absurd, this manifests as a procession of flagellating businessmen trudging their way through the perpetual congestion, hoping to find atonement through self-punishment like the masochistic monks from The Seventh Seal. Even when life beyond the immediate setting isn’t visible though, the noise of road rage and car horns can often be heard from just outside enclosed walls, rooting these trivial, woeful tales within a common dystopia.

Perhaps the only thing holding Andersson’s film back from total melancholy is its sharply attuned, deadpan satire, carried by his idiosyncratic ensemble and revealing a civilisation that has reached a point of unsalvageable stagnation. Comparisons to Jacques Tati and Wes Anderson’s playful mockeries of modern society are apt, especially in their meticulous manufacturing of eccentric structures to speak for their monotonal characters, though Andersson’s humour possesses a far darker edge than either. Without physical slapstick or whimsical montages driving its narrative forward, Songs from the Second Floor languishes in the uncomfortable silence of awkward interactions, washed out by drab, desaturated colour palettes sapped of life.

Although Federico Fellini’s cinematic chaos does not draw so clean a parallel, Andersson’s condemnation of an indulgent, undignified culture reveals this influence to be particularly potent. Much like the Italian director’s later films, Andersson’s surreal imagery and episodic narrative unveil the egocentric irony in human suffering, manifesting as miserable self-pity afflicting an entire civilisation. When strangers are beaten up in public, injured in a botched magic trick, and stuck in a train door, bystanders in Songs from the Second Floor watch on with blank expressions, preferring to keep a distance from those who desperately need help.

Then again, perhaps it is the very fact that everyone is occupied by their own personal burdens which keeps them from stepping forward. In a particularly Felliniesque metaphor, Andersson stages what seems like hundreds of travellers at an airport terminal dragging overloaded trolleys of luggage towards the counters, where hostesses wait with professional apathy. The soundscape of desperate groans almost sounds like a hellish torture chamber, and although the distance to cover is minor, it feels like an eternity away as bags begin to topple over.

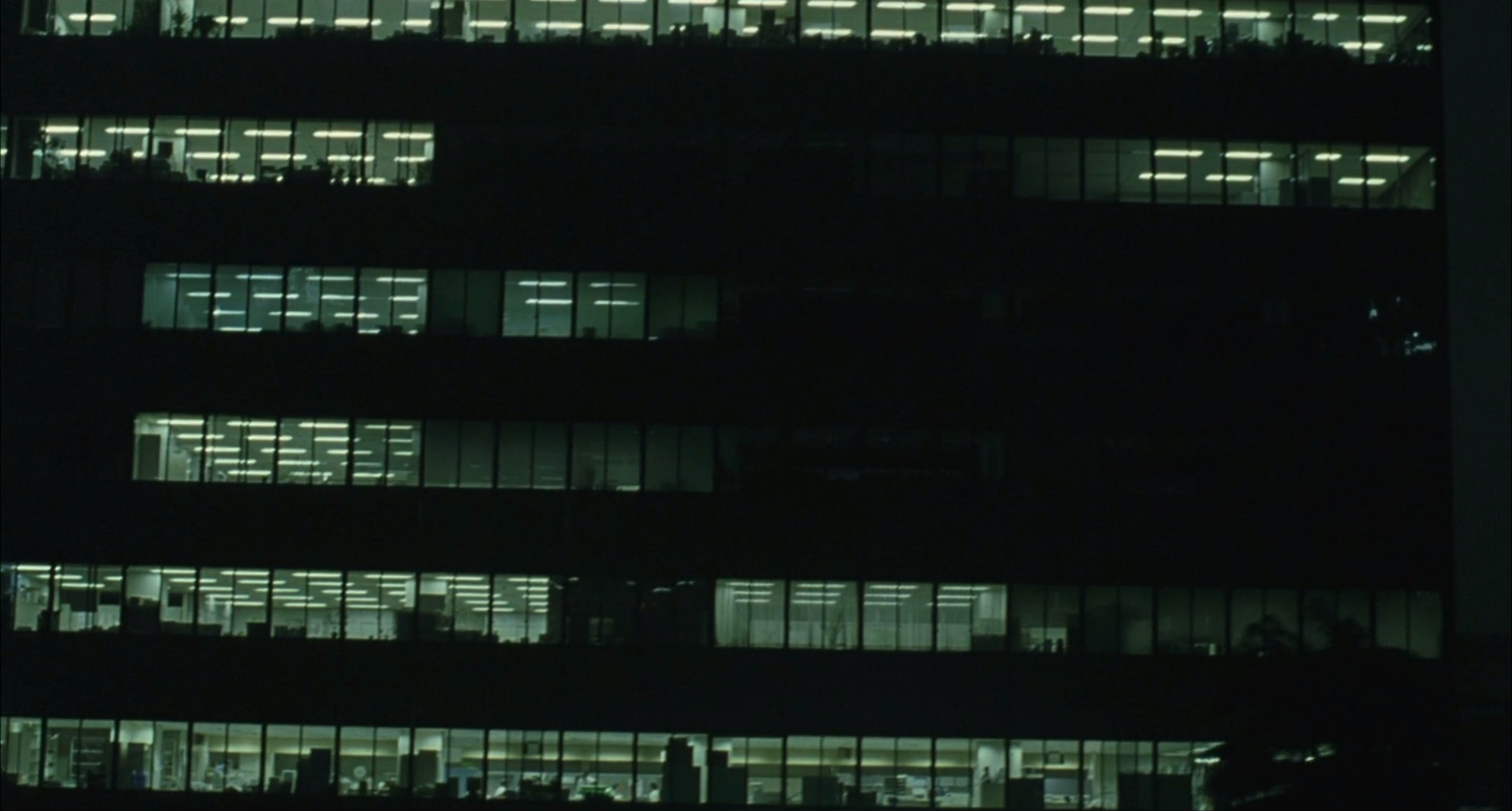

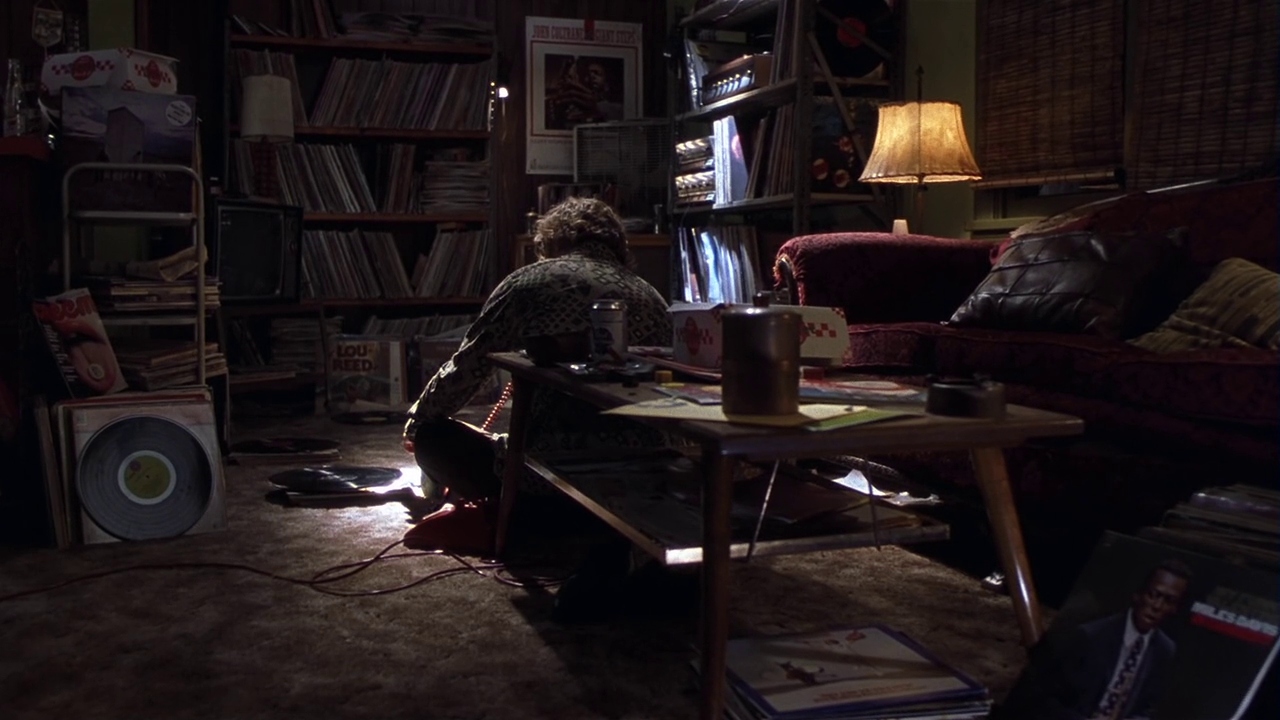

Clearly everyone has their crosses to bear, and for some in Songs from the Second Floor, these manifest quite literally. If Andersson centres any character in this expansive tapestry of miserable lives, then it must be the middle-aged salesman Kalle who burns down his furniture business, attempts to claim insurance on it, and decides to join his old friend Uffe hustling religious paraphernalia. Lugging a crucifix-shaped package through train stations and cafeterias, he expects to find some financial or spiritual salvation, albeit one which never materialises. Religion is reduced to nothing more than a cheap commercial enterprise, and when he decides to seek genuine solace in a church, even the vicar is too preoccupied by his own troubles to consider the needs of his congregation.

“At the end of your wits… so who isn’t? I’ve been trying to get my house sold for four years.”

This is not to say that Kalle’s world is absent of mysticism or empathy. The aggrieved entrepreneur is simply too blind or deaf to appreciate it, even ignoring the melancholy, operatic chorus sung by surrounding commuters on a train. Their shared sorrows swell in beautiful harmony, carrying over to the following scene in a diner as well where Andersson reveals just how far this song of suffering resonates. Neither does Kalle grasp the divine enlightenment that his son Thomas has been blessed with, yet which has tragically condemned him to a psychiatric hospital. “Beloved be the one who sleeps on his back,” he proclaims, quoting Peruvian poet César Vallejo, before continuing to exalt all those overlooked by a complacent society.

“Beloved be the bald man without a hat.

Beloved be the one who catches a finger in the door.”

This poetry is the reason Thomas has gone insane, Kalle claims, so it is ironic indeed that each visit ends with the salesman being forcibly removed by hospital staff for his furious breakdowns. The resemblance Thomas’ words bear to the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount is certainly no coincidence here. He is a Christlike figure, albeit one who has been debilitated by a culture which sees his wisdom and calls it madness. He is no Son of God, but neither was Jesus, Thomas asserts – he was simply a man who was tormented to death for his kindness.

Still, the guilt which lingers beneath society’s thin veneer of apathy cannot be entirely ignored. The only time Andersson’s camera moves in Songs from the Second Floor is at the point where reality almost entirely breaks down, seeing it track backwards along a train platform where a man with bleeding wrists follows Kalle. This is Sven, we soon learn, a man who Kalle once owed money to yet eventually took his own life before being repaid. Kalle was not directly responsible for his death, though he sheepishly confesses to feeling relieved upon hearing the news.

Not far behind Sven is another spectre, though this one manifests as a far greater trauma in European history. Approaching Kalle with a noose around his neck, a young Russian who was hung by Nazi Germany is looking for his similarly deceased sister, hoping to apologise for his transgressions. Kalle has never met him before, yet still he feels a sense of shame as the foreign ghost stalks him through the city. “You’ll have to forgive me, but I’m afraid I can’t help you because I can’t understand what you’re saying,” Kalle weakly apologises as the boy pleads to him in his own language, though this is evidently little more than a convenient excuse for an embarrassingly disinterested man.

When all is said and done, was Sweden’s diplomatic policy of neutrality in World War II not a radical position in itself, granting themselves permission to sit by as millions died across the Baltic Sea? Elsewhere at a nursing home, the staff who celebrate a senile general’s 100th birthday ignore his Nazi salute and deluded greeting to Hitler’s right-hand man, as Andersson further characterises a nation whose self-proclaimed tolerance is also its greatest flaw. These ghosts may fade into obscurity, but they never truly disappear as long as the living refuse to address the torment they have inflicted and suffered, leaving the dead to amass an overwhelming force in the film’s closing minutes.

Just outside the city’s borders, Kalle meets with his friend Uffe, who has given up his business. “How can you make money on a crucified loser?” he grumbles, hurling crosses onto a pile of junk. Religion has apparently fallen so far from the mainstream, no one even is even seeking the empty promises of its cheap icons. We can’t quite make out the faces of the people trudging towards him in the far distance, but when Uffe finally leaves, Kalle is quick to identify the leader.

“Why are you chasing me, Sven? Why are you tormenting me? I can’t make it up to you. How could I do that? You have no relatives. What can I do? Sven! Can we not treat each other decently? Forget it all. The past… just look ahead!”

The trash that he throws is enough to scare some off, and yet a hundred more rise from the earth, continuing their zombie-like march. Kalle whimpers, resigned to his fate, and though Andersson does not linger on this shot long enough to reveal what that might be, we do finally recognise the girl at the front.

After all, how could we ever forget that chilling image of a blindfolded child being led to her death along a cliff top? Like Sven and the Russian boy, Anna’s spirit continues to haunt those who call society’s evils ‘necessary’ and shirk moral responsibility. It wasn’t long after her demise that those who bore witness tried to drown their guilt at a hotel bar, we recall. There, an elderly aristocrat vomits on the countertop, a woman struggles to pick herself up off the floor, and one man’s demented cry eerily spreads through the establishment. “Where are we?” they collectively moan in confused discord, as if coming to the realisation that this modern hell has been nightmarishly fashioned from the reality they once believed in. As far we are concerned in Songs from the Second Floor too, this existential question might as well echo across the entire city.

Songs from the Second Floor is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.