The Coen Brothers | 1hr 56min

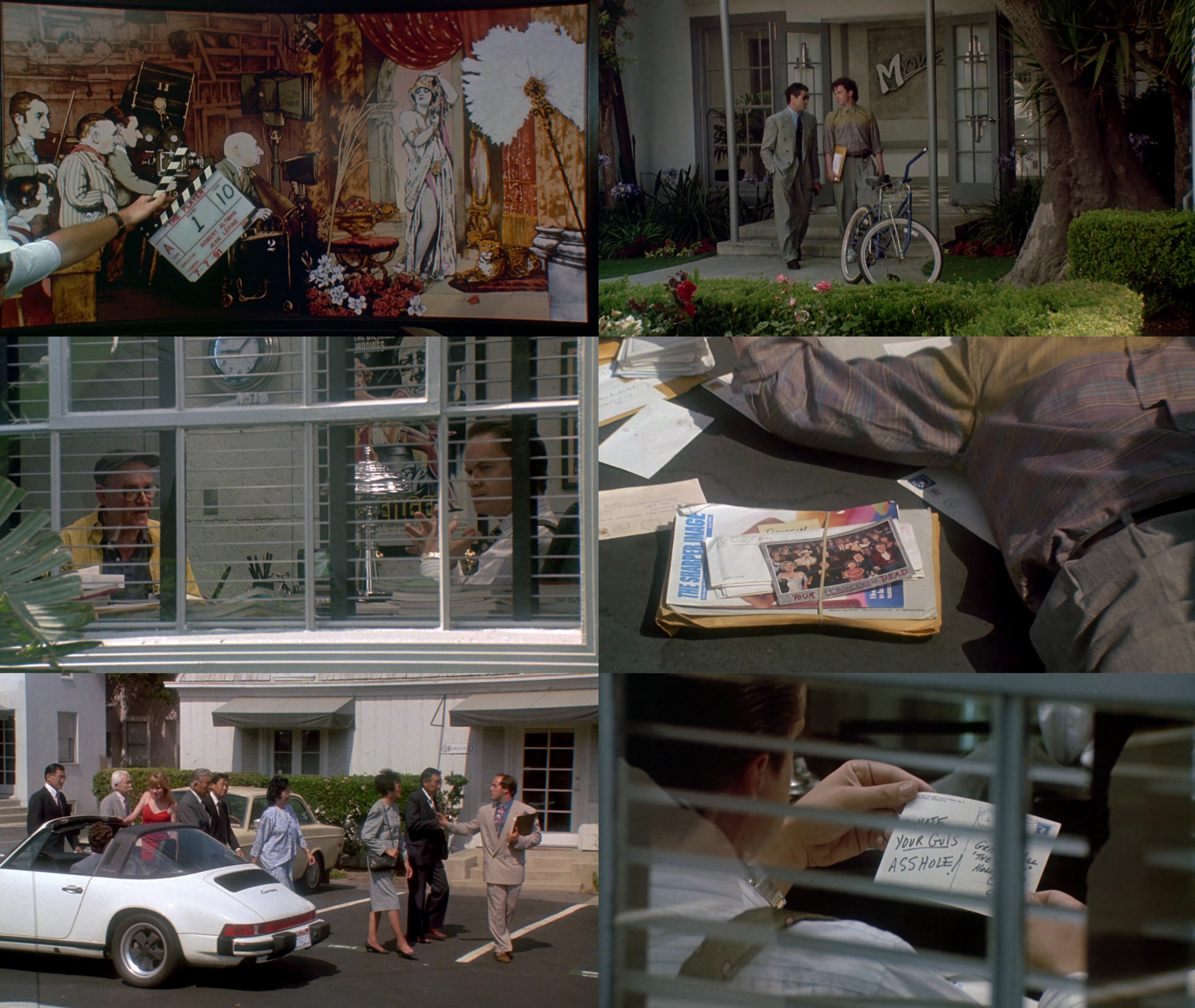

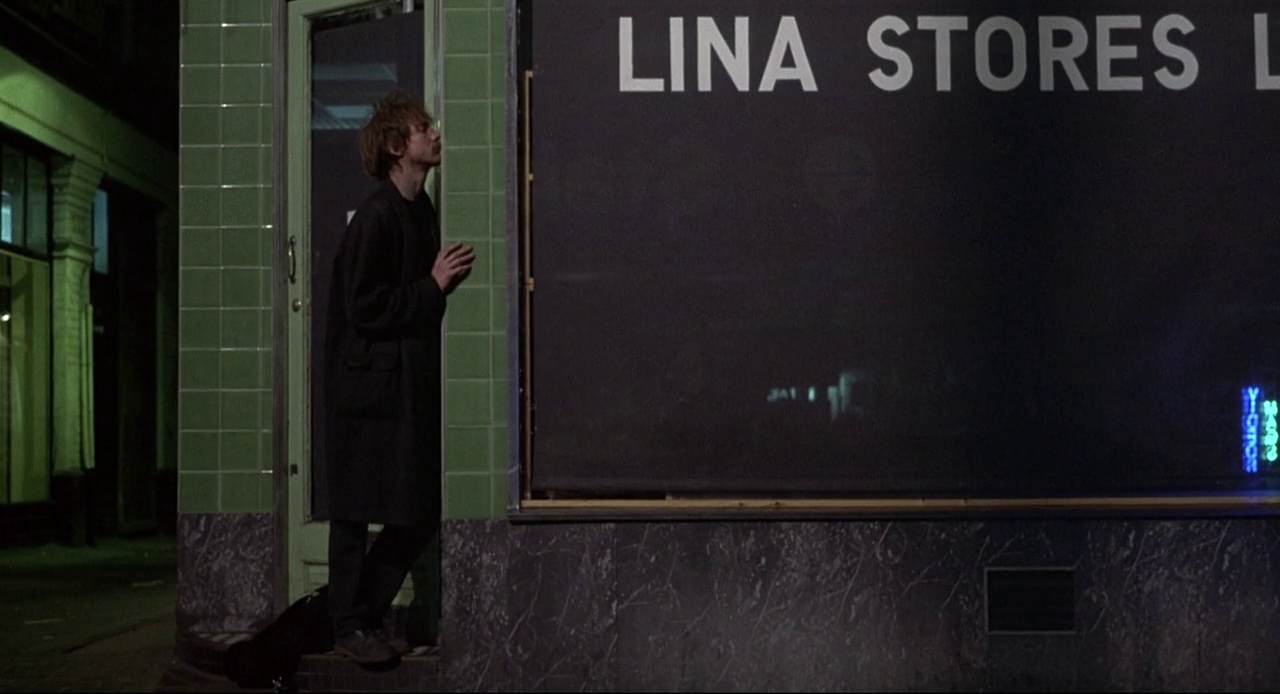

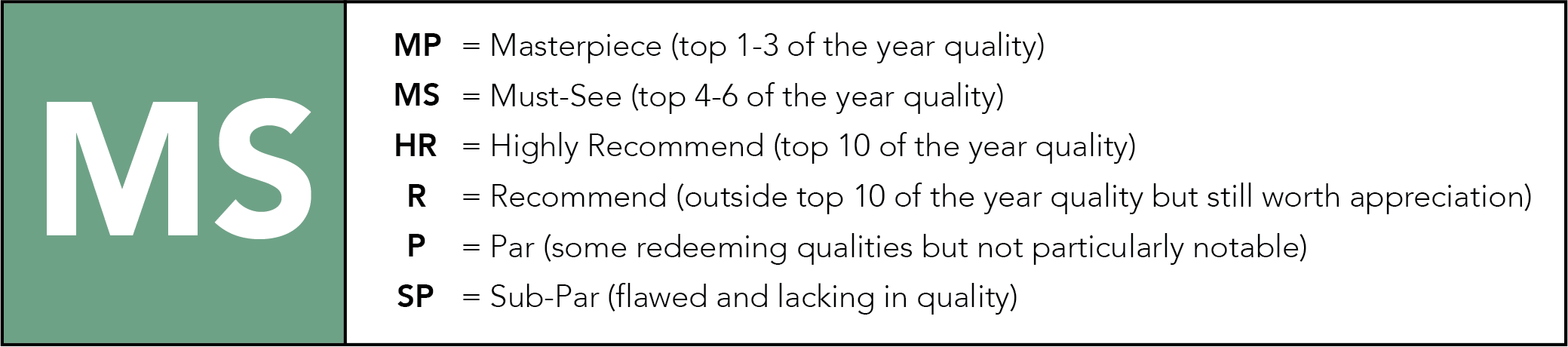

The hotel that Broadway playwright Barton Fink moves takes residence in when he gets his big Hollywood break offers a deeply unsettling welcome to 1940s Los Angeles. The countless shoes lined up outside the doors of drab, low-lit corridors would suggest the presence of many other guests, as do the cries and moans that disrupt Fink’s sleep – and yet throughout his time here, most of these people remain entirely unseen. As he sits down to write a screenplay for the newest Wallace Beery wrestling flick, his room’s depressing palette of beiges and reds offer little in the way of inspiration, while the peeling wallpaper and whining mosquito only serve to distract his weary mind.

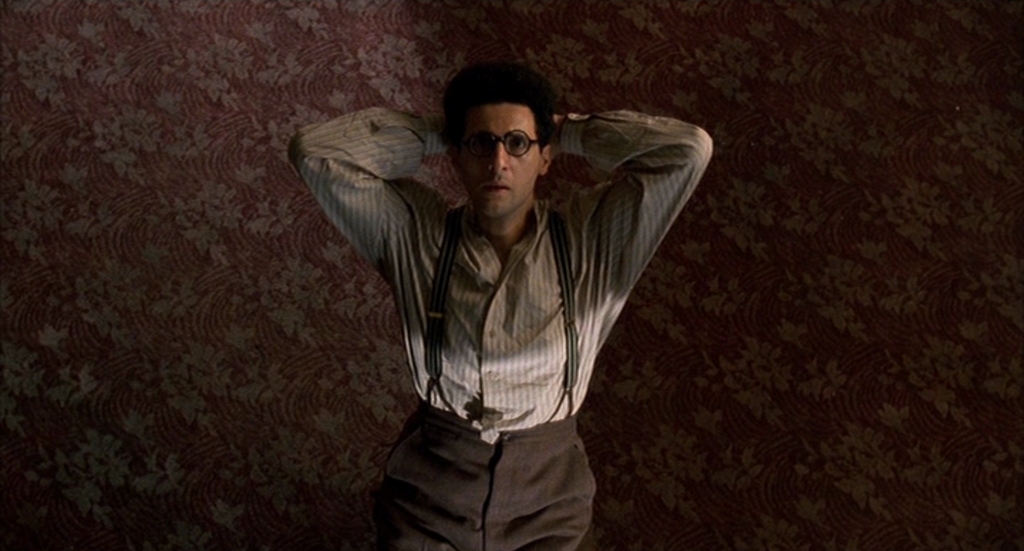

If there is any saving grace, then it is in that single painting hanging above his desk, depicting a woman sitting on a beach and shielding her eyes from the sun. It does not belong among history’s great works of art, nor does it serve as an all-important commentary on the average working man, which Fink so desperately strives to reflect in his own creative craftsmanship. Nevertheless, it is a vision of freedom beyond this Kafkaesque hellhole he has wound up in, bringing hope even as his patience, sanity, and motivation are agonisingly sapped into oblivion.

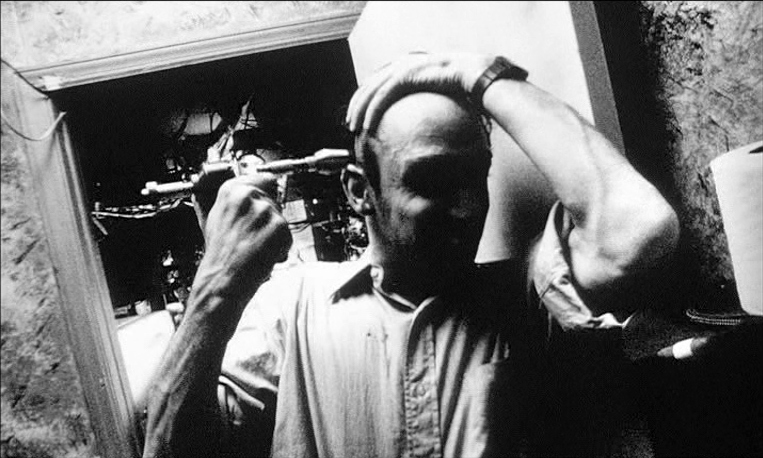

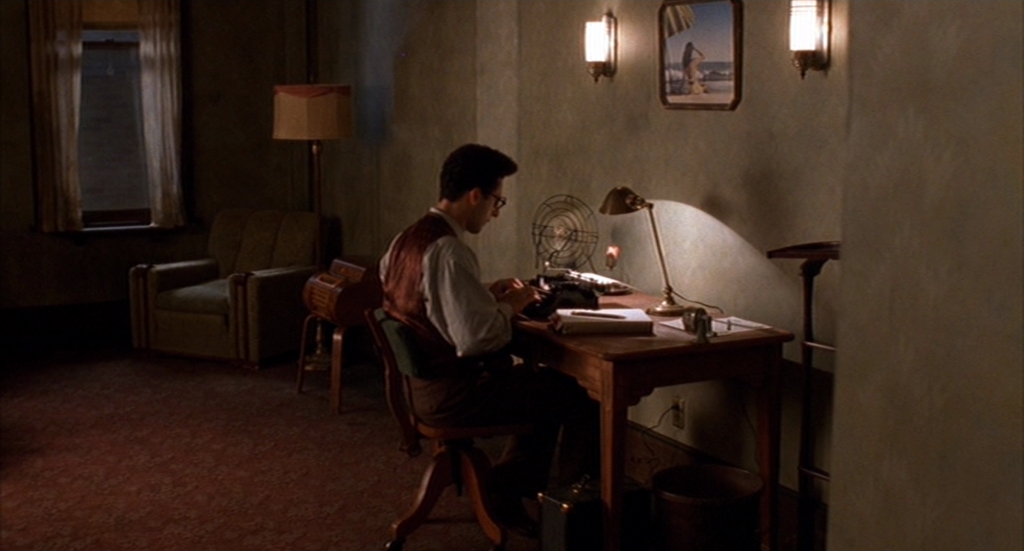

Not that Fink is necessarily a complete victim in these bizarre circumstances, even if he would like to present himself as an innocuous straight man. In this anxious writer, the Coen Brothers deliver one of their most idiosyncratic characters, fraught with all the arrogance and neurosis of a Woody Allen protagonist. His giant glasses and shock of frizzy hair distinguish him as a New York intellectual in this foreign land, and John Turturro’s agitated performance carries a haughty self-regard which sets him up for failure from the start. “I’m a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living!” he furiously brags at a dance when his pride is slighted, though a fellow partygoer is quick to shut him down with a blow to the face.

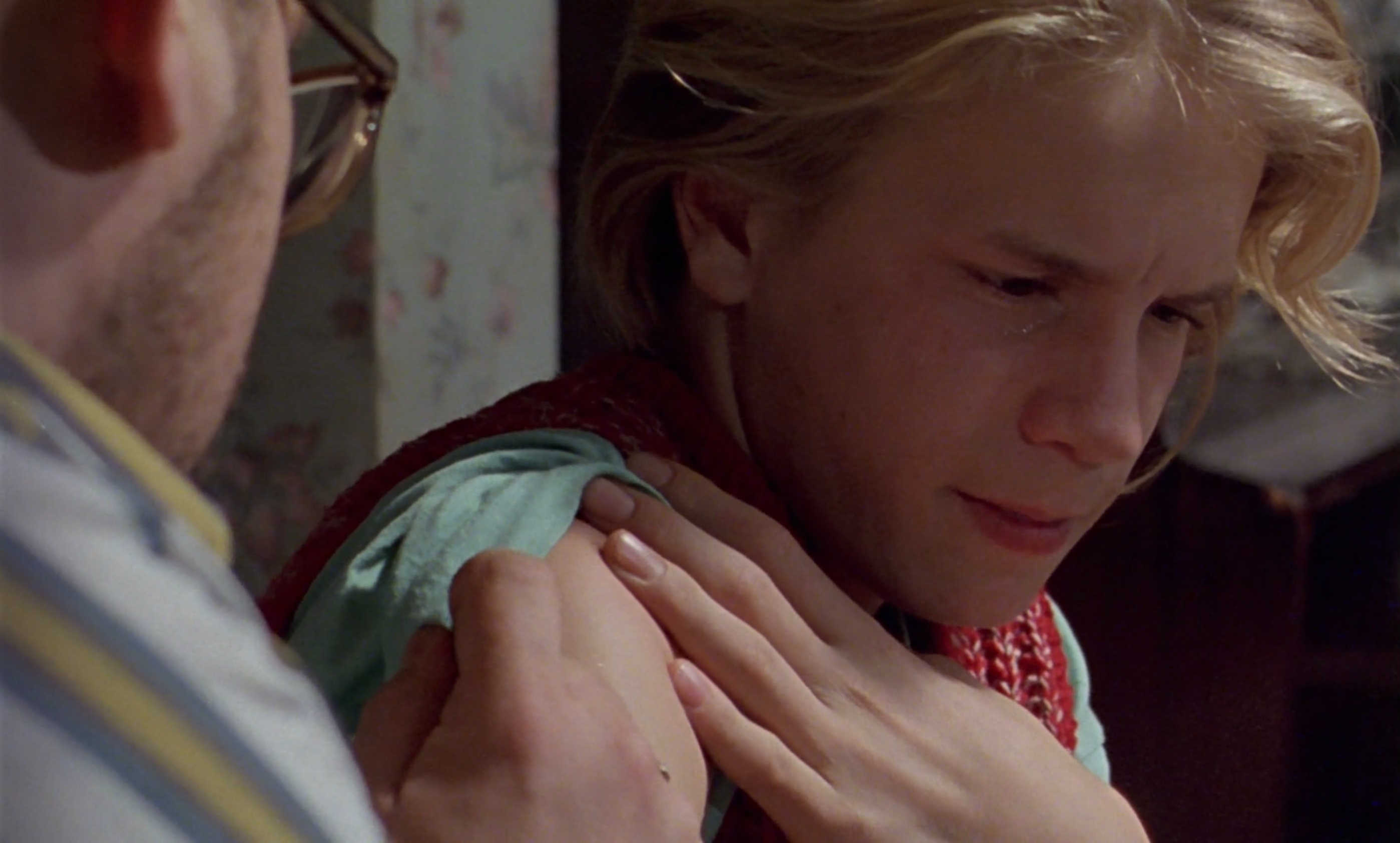

Perhaps then he will find a home among the producers and artists of Hollywood, though there too the Coen Brothers thwart him with an ensemble of eccentric egos whose objectives and principles rarely align with his own. The enormous expectations that overbearing executive Jack Lipnick places on Fink are far more burdensome than encouraging, and novelist W.P. Mayhew’s exploitation of his trusted secretary deeply disappoints his biggest fan. Audrey has been ghost writing her boss’ recent scripts, Fink is shocked to discover, while he squanders his gift with alcoholism and idleness. What once looked like a haven for America’s creative types now reveals itself to be little more than a corrupt, money-driven business, binding its idealists within chains wrought by unconscionable contracts and poor wages.

As peculiar as Fink’s neighbour Charlie Meadows may be, he initially seems the most down-to-earth of the supporting players in this film. Played by John Goodman with affable warmth, he befriends Fink early on, emerging as the only other hotel guest to reveal his face. Between the two, the Coen Brothers write dialogue that crackles with self-deprecating irony, seeing the young writer proclaim a desire to write about real issues while interrupting Charlie’s attempts to share his own apparently authentic experiences. Fink’s belief that art must reflect reality is not only at the core of his struggle in Hollywood, but a notion that is directly undercut by the very story he is living in, warping Barton Fink into a remarkably absurdist work of metafiction.

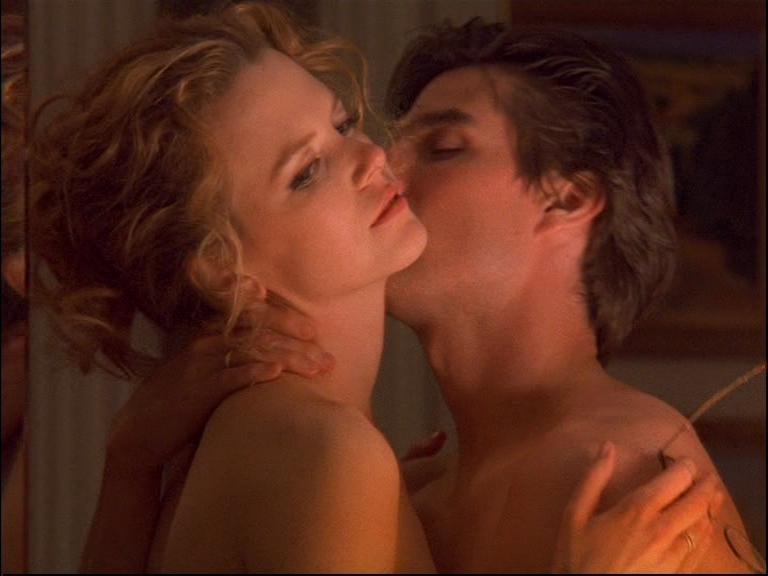

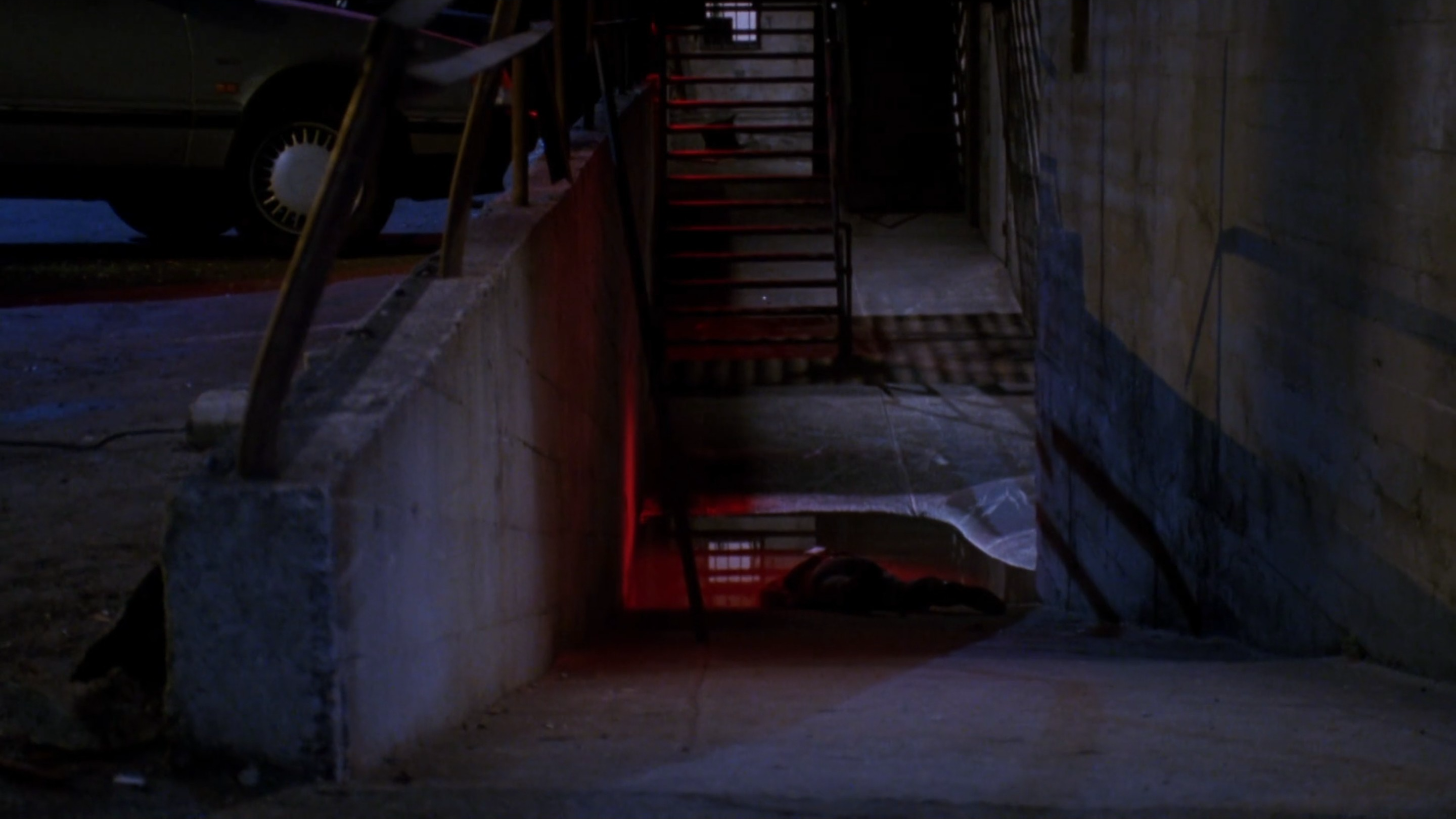

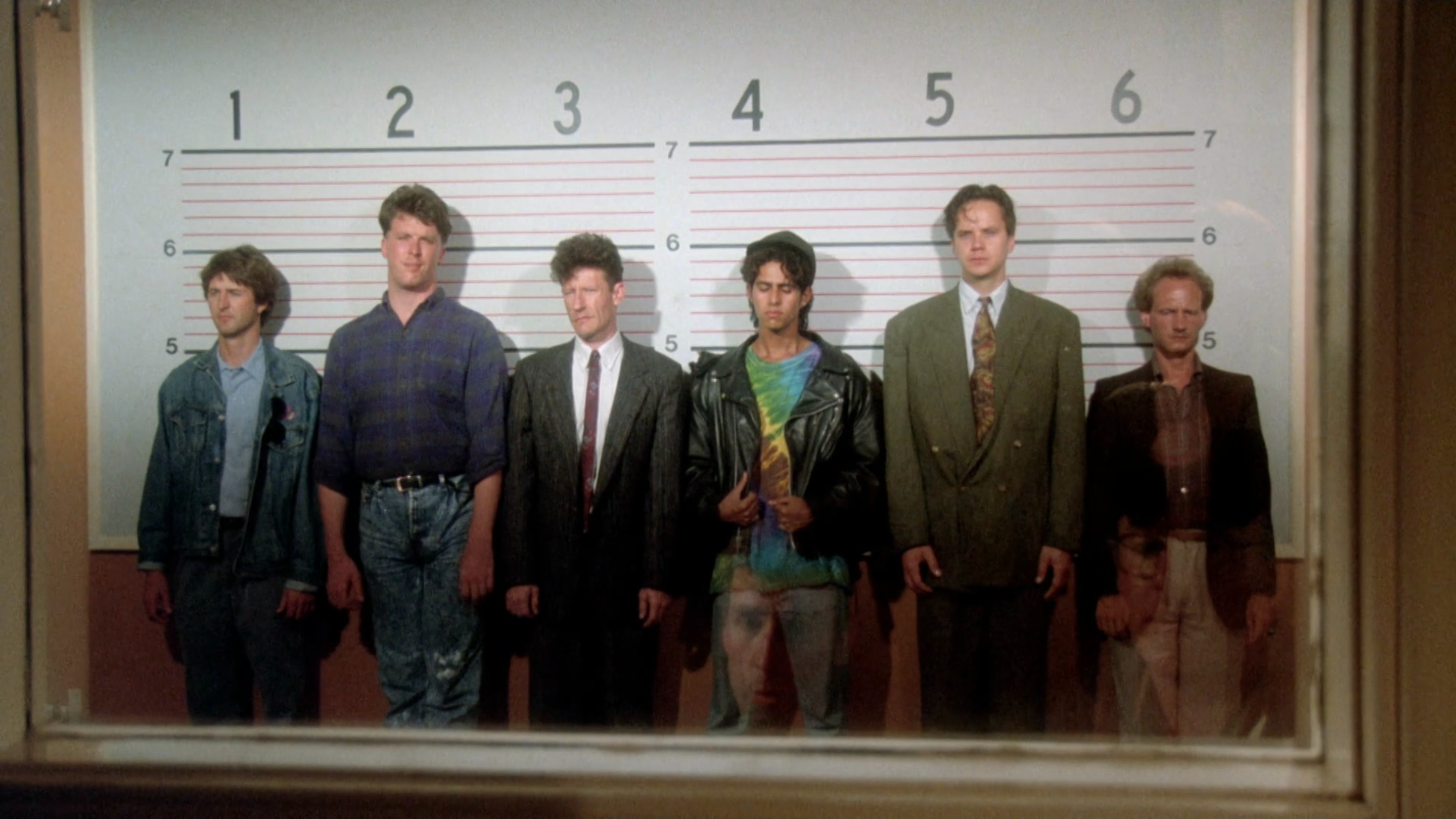

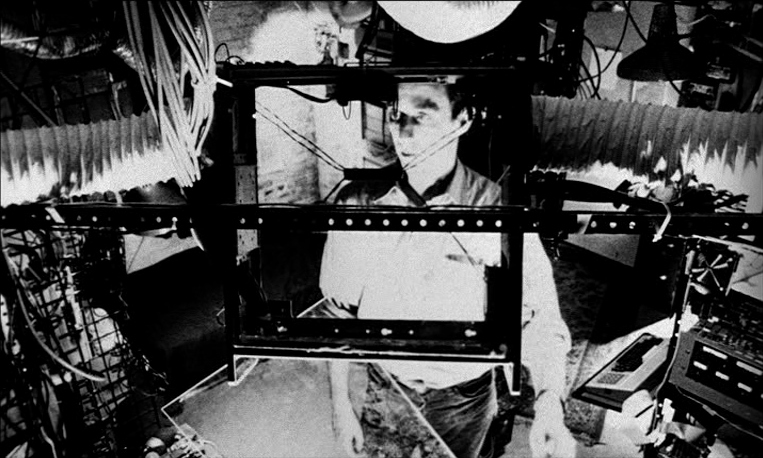

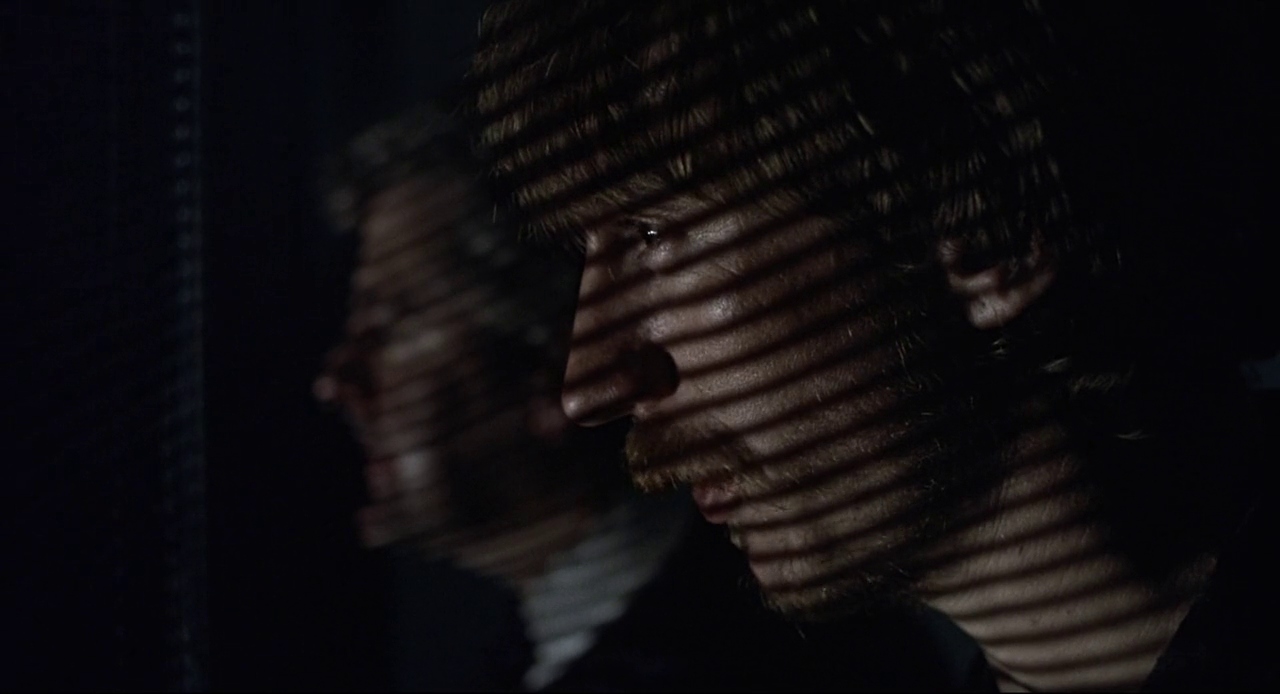

After all, the longer we spend in this hotel, the more it seems to become a harrowing embodiment of our protagonist’s own tortured mind. Roger Deakins’ camera spirals in overhead shots and romantically drifts away from Fink’s sexual encounter with Audrey, heightening every emotion that passes through this room. The biggest departure from the ordinary though comes when he awakes one morning to find her dead body next to him in bed, bleeding out onto the floor and implicating him in a murder he didn’t commit. Charlie’s assistance in helping to dispose the body should be the first clue that Fink’s closest friend is secretly a notorious serial killer, but once he disappears under the guise of visiting New York and kills Mayhew as well, it is far too late to escape accusations of collusion.

It is somewhat ironic then that only in the wake of incredible tragedy does Fink’s writer’s block lift, unleashing a torrent of creative inspiration in a montage of quick dissolves – not that Lipnick is terribly impressed with the results. According to him, Fink’s manuscript is nothing more than a “fruity movie about suffering,” and the option to leave Hollywood altogether is rapidly squashed by a reminder of the unbreakable contract which brought him here.

“Anything you write will be the property of Capitol Pictures. And Capitol Pictures will not produce anything you write. Not until you grow up a little. You ain’t no writer, Fink. You’re a goddamn write-off.”

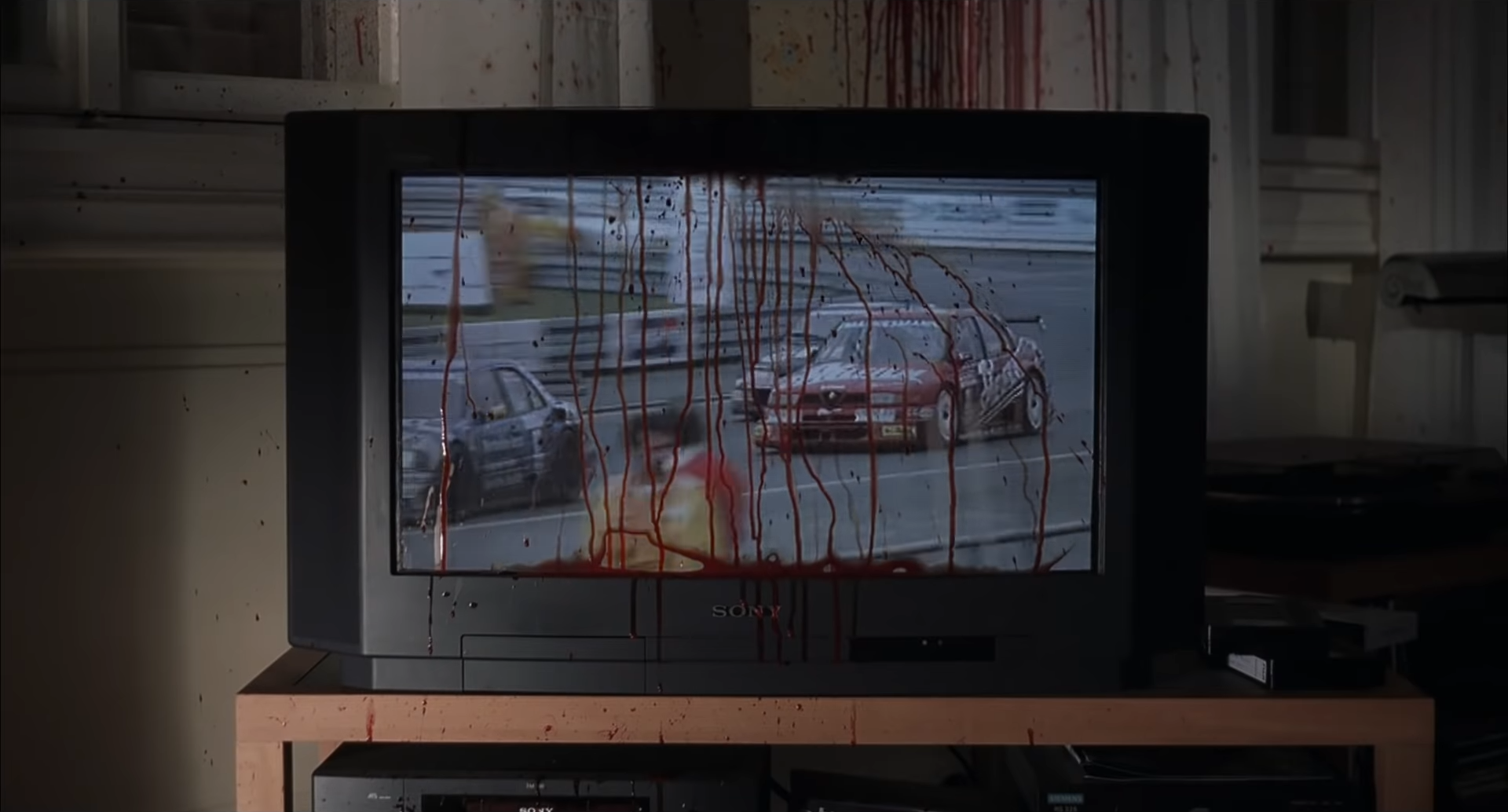

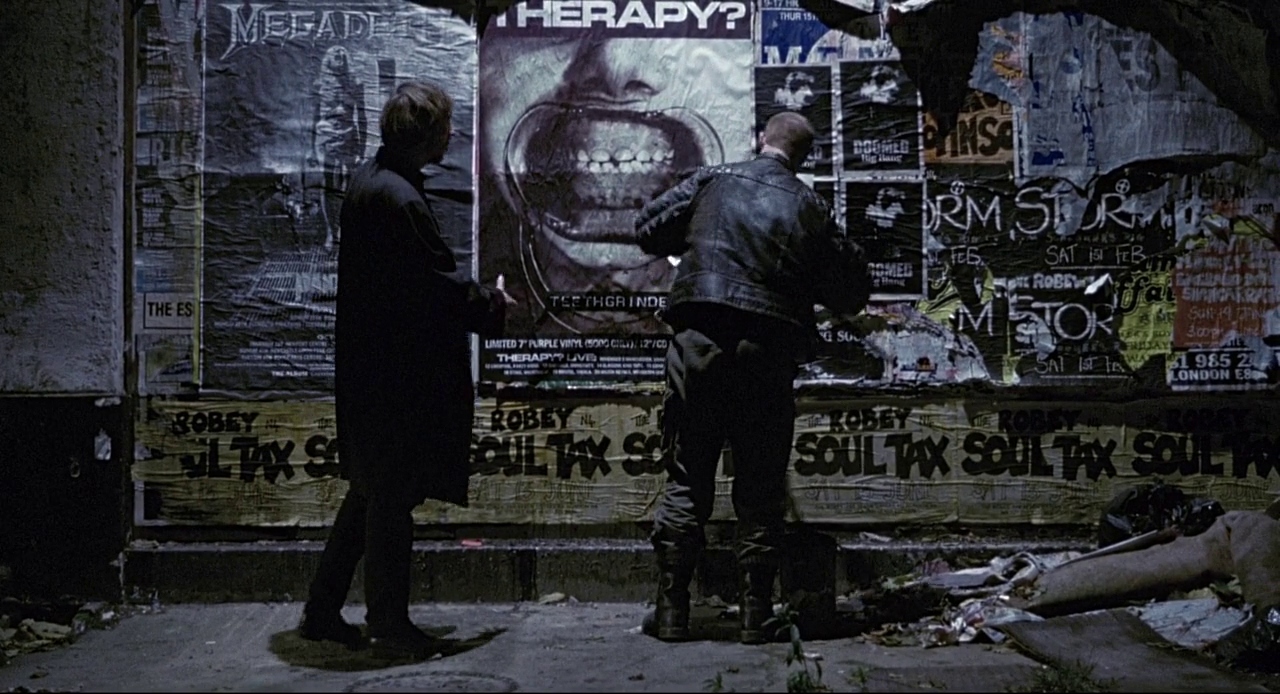

This paradoxical arrangement is the ultimate punishment for an artist such as Fink, whose greatest talent is now effectively rendered useless. All hopes for a prosperous career in the film industry are gone, and there is no more concealing the hellish underworld which lurks beneath Hollywood’s superficial dream machine, as the hotel finally transforms into a blazing inferno. Flames arc up behind Goodman as he returns to eliminate the detectives on his tail, and suddenly he appears more terrifying than ever, becoming a shotgun-wielding devil who menacingly booms Fink’s own pretentious words back at him.

“Look upon me! I’ll show you the life of the mind!”

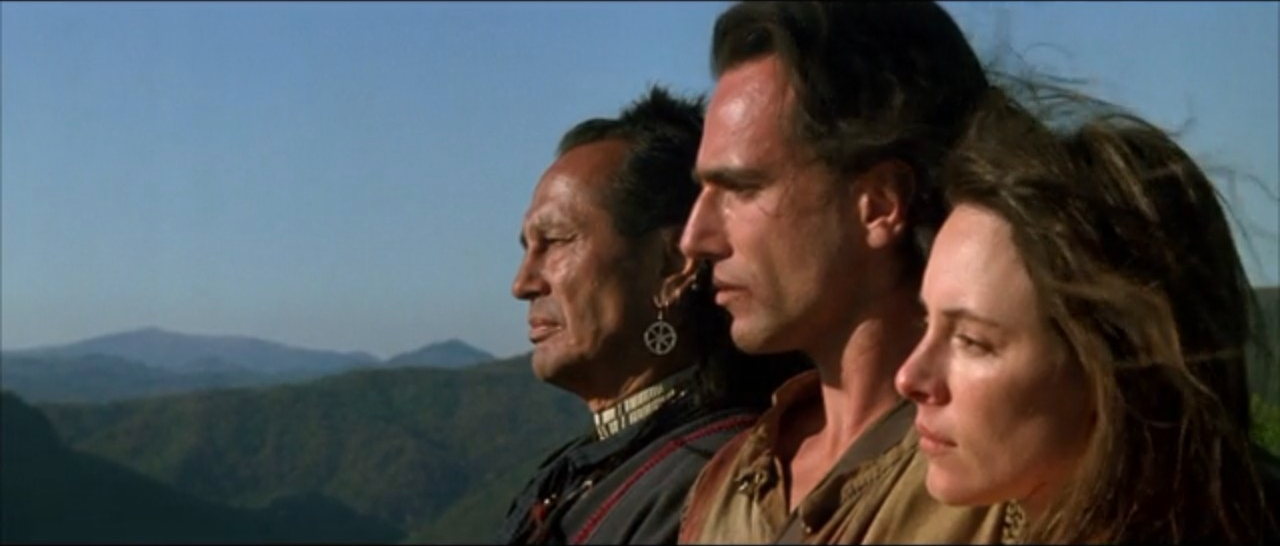

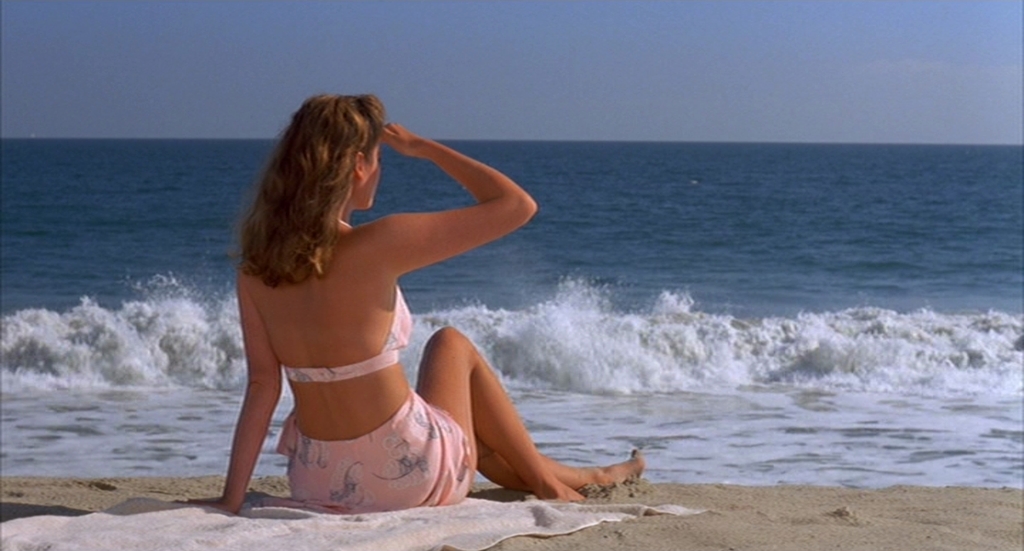

Within the spectacle and symbolism, the Coen Brothers reveal the damning truth of Fink’s intellectual hypocrisy that his socially conscious writing could never fully reckon with. To acknowledge one’s own ignorance is to find peace in life’s confounding puzzle box, and perhaps he begins to recognise this as he makes his way down to the beach in the film’s closing minutes, simply savouring rather than questioning the beautiful conundrum he encounters. He does not know anything about this woman other than the fact that she lives completely outside the hell that is Hollywood, and as she sits down on the sand, she inexplicably strikes the exact same pose as the painting from his hotel room. What was once a vision of freedom now manifests by fate before Fink’s very eyes, letting life mimic art rather than forcing its dull contrivances onto our creative escapes and dreams. There is a pleasing harmony found in the elusive formal patterns of Barton Fink, though it is in trying to conquer such mysteries that man’s ego ensures its own downfall, paving the way for a quiet, graceful acceptance of the ineffable.

Barton Fink is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.