Claude Berri | 2hr 2min & 1hr 54min

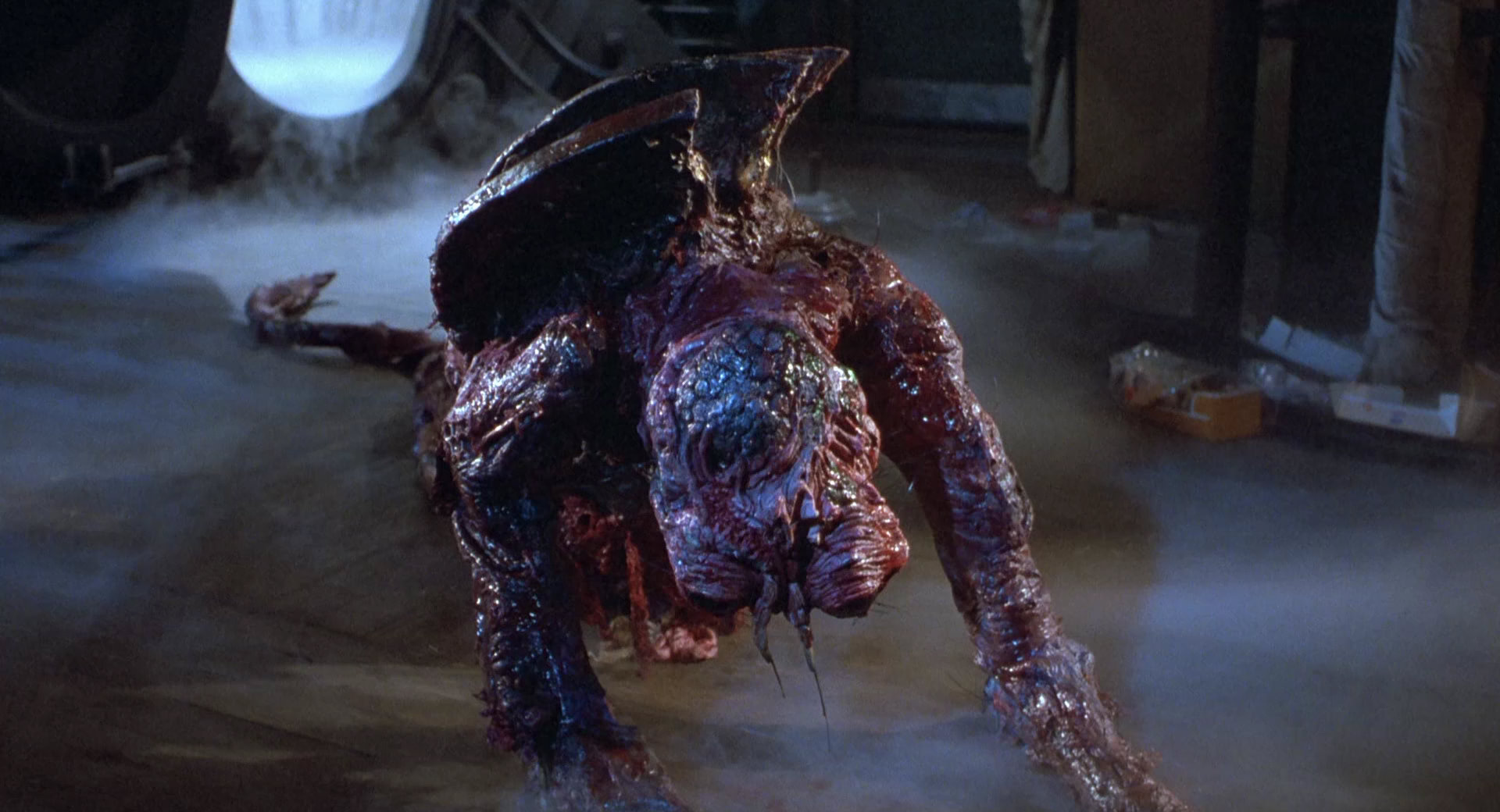

In a rural French village, set nine years apart, a pair of fables unfold around two blocked springs.

The first is located on the property of cheerful hunchback Jean, who has come from the city with his family to start a new life as a farmer. Seeking to claim the land’s water as their own though, neighbours César and Ugolin have covered it with cement and soil, keeping him from ever knowing of its existence. Now all they must do is sit back and watch, as Jean’s struggle against the elements pushes him to the brink of destitution.

The second spring is the town’s main water supply, hidden in the crevices of a nearby mountain. When Jean’s grown daughter Manon stumbles across it almost a decade later, she immediately acts on the resentment she has harboured ever since her father was driven to an early grave, blocking its flow with clay. The plot to destroy Jean may have been committed by two neighbours, but the entire community was well-aware of it, and thus they are all responsible for his untimely passing. If water is the source of all life, then it is no surprise that its suppression inevitably leads to needless deaths in both instances, formally mirroring the tragedies of Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring against each other. Together, they take on an epic scope, as Claude Berri plays out the Shakespearean fall of two feuding families through greed, scorn, and betrayal.

Based on the two-part volume novel ‘The Water of the Hills’ and shot in back-to-back productions, it is tough to consider these films as anything but a single work, strengthened by the formal connections that stretch across their conjoined narratives. César and Ugolin are our main characters in both, taking on the mantle of antiheroes from the moment they accidentally kill their neighbour Pique-Bouffigue in an altercation over his spring. Perhaps there is a bit of contempt here too, especially given that César was once in love with Pique-Bouffigue’s sister, Florette, who abandoned him many years ago.

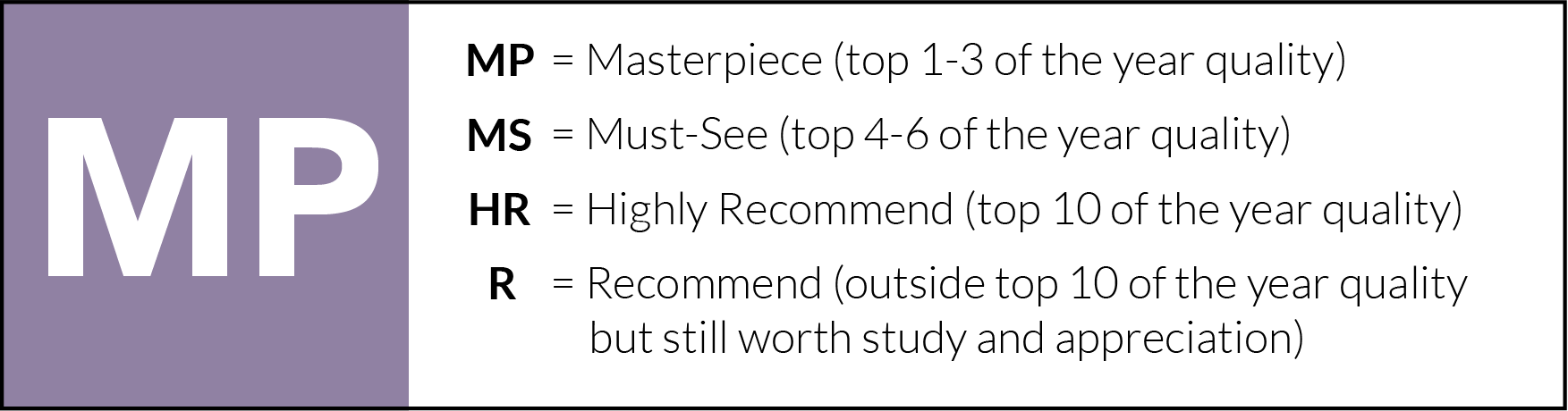

If this is indeed the case, then it would also be safe to assume that César holds a similar disdain towards Florette’s disabled, newly-arrived son, Jean, thereby adding a second layer of motivation to ruin his life. So bitter is César that for the two years the hunchback lives on that farm, the old man cannot even bring himself to meet him face to face, instead choosing to watch his suffering play out from the comfortable distance of his home. While his nephew Ugolin directly implicates himself by cruelly denying Jean the use of his mule, it is César whose heart has been corrupted by resentment, remaining all too happy to sacrifice his neighbour’s wellbeing to accomplish his own goal of starting a carnation farm.

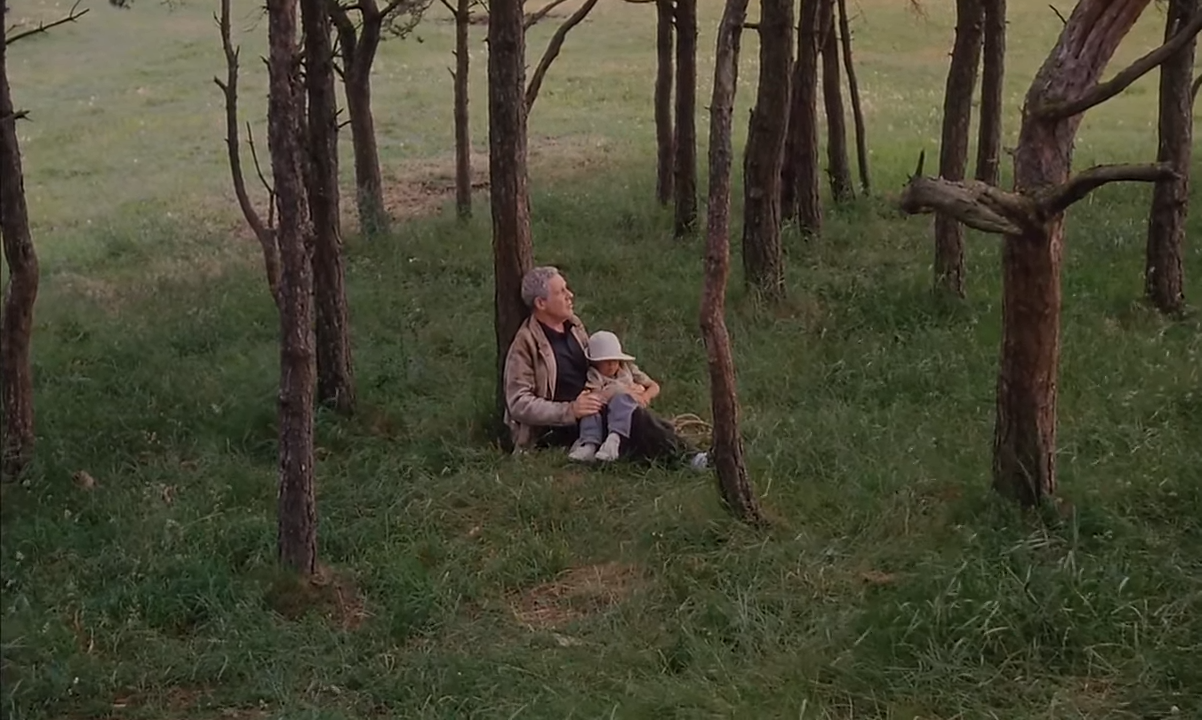

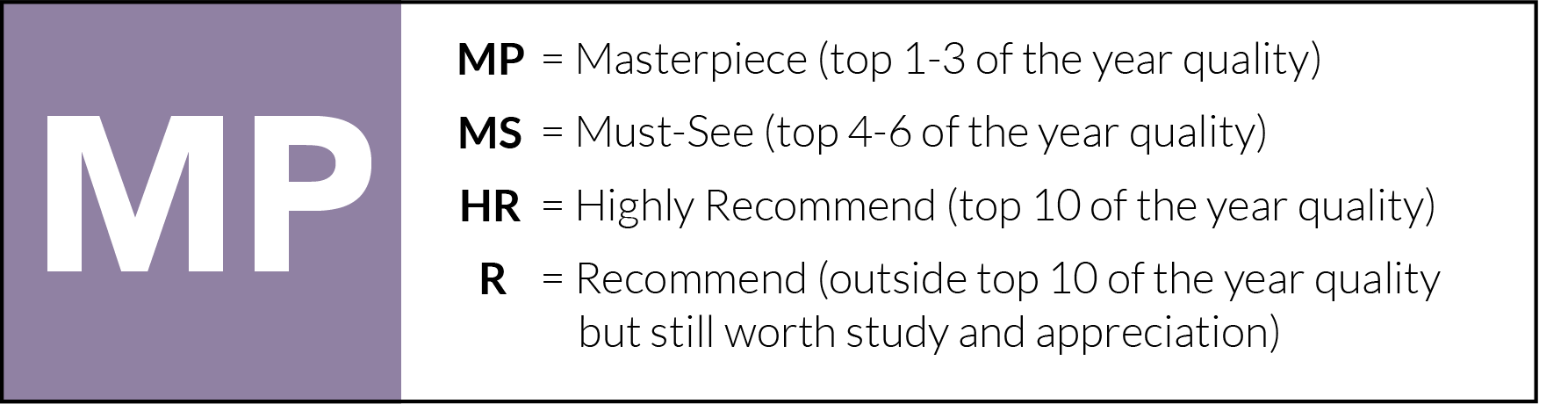

The beauty of 1910s France’s sun-dappled pastures and settlements does well to mask the malice which resides in its seemingly humble farmers, as Berri crafts astounding visuals across both parts of this duology, basking in the golden glow of the countryside’s natural light. His establishing shots are astounding, setting quaint cottages against vast backdrops of majestic mountains, lush hills and valleys provide fertile ground for locals to cultivate. From inside their darkened homes, Berri often cuts out windows of light through which neighbours often spy on each other, though these interiors also frequently carry through that outside warmth through dim oil lamps and small fires. Across the four hours that Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring unfold over, Berri delivers enough painterly compositions to hang in a gallery, taking advantage of his widescreen frame to stage actors across superbly detailed period sets and landscapes.

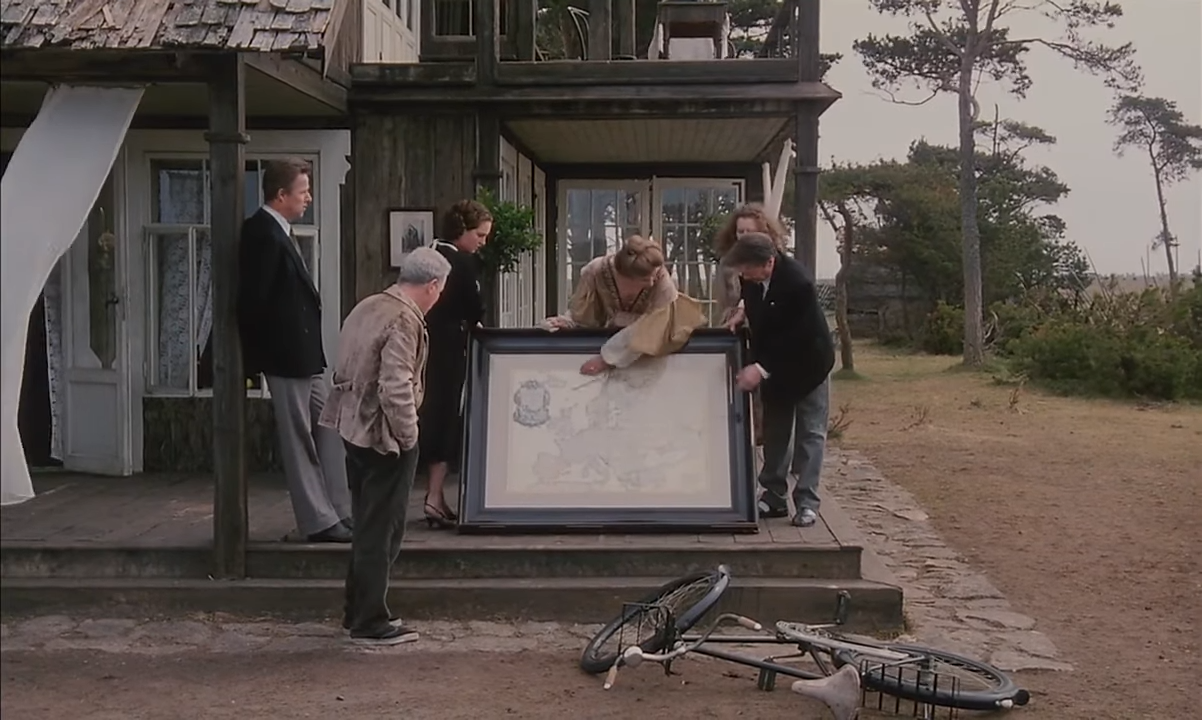

When the local weather rears its nasty head though, Berri is not afraid to shed a harsher light upon these environments, testing the endurance of Jean as he struggles to grow produce in unpredictable conditions. When a dust storm strikes, Berri lays a musty, yellow filter across the lens, while winter conceals the land’s green and gold hues with pristine white blankets of snow. When clouds gather, the rain is always either too heavy for Jean’s vegetables, or taunting him from a distance as it falls several miles away. “There’s nobody up there!” he angrily swears to the sky, but each time he is ready to give up, he picks himself up again.

For César, this resilience is endlessly frustrating, though from the outside we can’t help but admire the bright optimism of Gérard Depardieu’s performance. His spirit is indomitable, working against every obstacle thrown his way right up until he is fatally struck in the head by a rock during his attempt to build a well. The incident may be an accident, but César and Ugolin know very well that the guilt lies with them – as does Manon when she discovers them unplugging the blocked spring right after they purchase the property. “I hereby name you King of Carnations,” César sardonically proclaims, baptising Ugolin with water from the earth, though soon enough the young florist will wear this title with great shame.

When Manon cuts off the town’s water supply nine years later in Manon of the Spring, the community is quick to lay blame on César and Ugolin – not for blocking it themselves, but for provoking God’s righteous anger. Where Berri’s staging once isolated the hunchbacked farmer from the derisive villagers, it is now the uncle and nephew who are ostracised, shrinking into small, lonely figures. Church attendance numbers surge with panicked locals suddenly “full of faith and repentance,” while the priest himself implicitly directs his homily towards those two men who everyone quietly recognises as the incidental culprits behind Jean’s death.

“I once read in a secular work a Greek tragedy, about the city of Thebes struck by a violent plague because of the king’s crimes. So I ask myself: is there a criminal among us?”

The feelings that Ugolin begins developing for Manon only further propagates his shame, though only on the most selfish level. Unlike César, he is a fool who lacks total self-awareness, and thus cannot comprehend the concept of regret or social decorum. His advances are awkward and obsessive, only deepening Manon’s disgust towards him, while she in turn grows closer to young schoolteacher Bernard. When Ugolin finally takes his life in despair, Berri does not even grant him the grace of our full attention, relegating his meagre, hanging body to the background of a long shot.

The return of the town’s water comes too late to save Ugolin, not that Manon particularly cares. The timing is impeccable, as it is only a short while after she unplugs the spring that the local fountain leaps back to life during a religious procession, seemingly reviving it through prayer. God’s love once again shines down on the village, felt by all except for César who must not only confront his grief, but also a final, devastating twist of the knife.

Jean was not Florette’s child by another man, he learns from an old acquaintance visiting town, but rather the son she bore from César himself. The tragedy is heartbreaking, though not so much as to overshadow the irony of his self-destruction, wrought by arrogance and bitterness. “Out of sheer spite, I never went near him,” he mournfully reflects in his final letter.

“I never knew his voice, or his face. I never saw his eyes, that might have been like his mother’s. I only saw his hump and the pain I caused him.”

As César’s voiceover expresses real regret for the first time, Berri’s camera gracefully floats by the items in his bedroom. An envelope addressed to Manon, containing his confession and intent to leave his estate to her. A pair of spectacles, folded neatly in front. An old family photo, depicting the blood ties he has tainted through the ghastly act of filicide. Finally, we find César himself combing his hair in the mirror, preparing to lay down for the last time. Like Oedipus unknowingly slaying his father or King Lear’s hubris destroying his children, César joins history’s lineage of tragically flawed patriarchs, inadvertently cursing their own families as fate’s ultimate punishment. The stage upon which this plays out in Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring is not located within the grand halls of historical power, but as Berri paints out in the warm, intimate scenery of rural France, tragedy may topple pride in even the humblest of settings.

Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring are currently streaming on The Criterion Channel and SBS On Demand, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV and YouTube.