Andrzej Żuławski | 2hr 4min

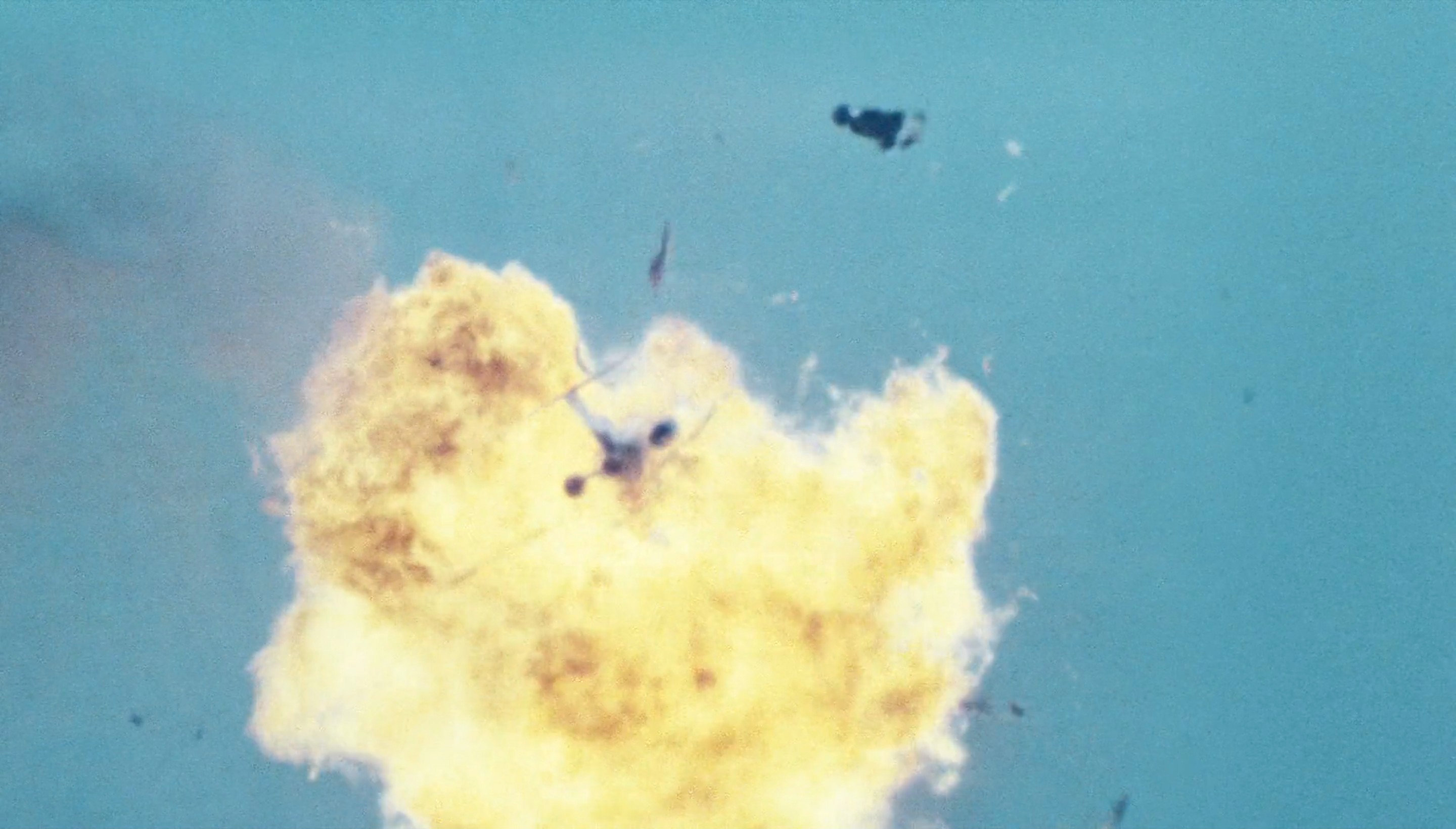

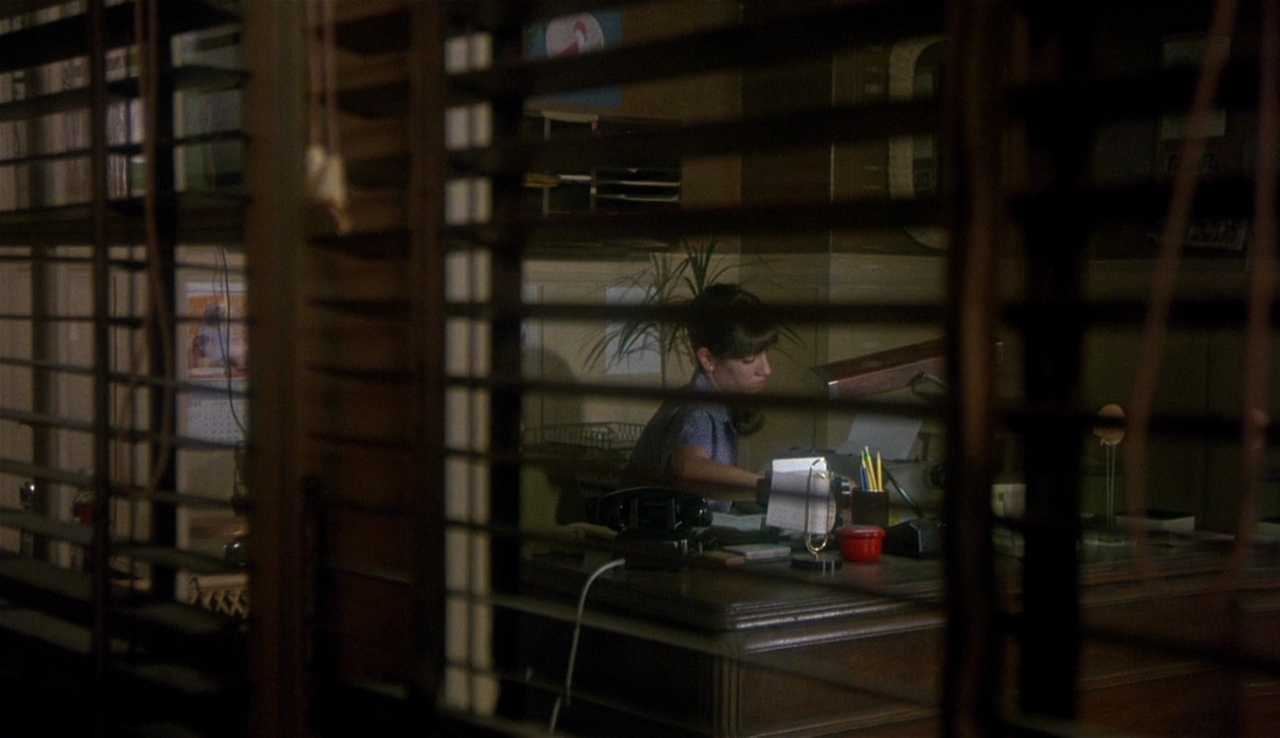

There is something growing in the apartment where Anna resides with her son, Bob, and it is plain to see that it isn’t quite human. The first time we meet the creature, it is a grotesque, writhing mass of tentacles, pulsing with life in her bathroom. “He’s very tired. He made love to me all night,” she tells the private investigator hired by her estranged husband Mark to watch her movements, before beating him to death a broken bottle. When we meet it again, it has since sprouted an elongated head with two beady eyes, and again later Mark witnesses it making love to his wife in the kitchen.

Whatever this Cronenbergian body horror may be, its arrival has coincided with a cataclysmic crisis in Anna and Mark’s marriage. Too long have they been living in a household of abuse, pushing Anna to seek out romance with drug dealer Heinrich while Mark disappears into his job as a West Berlin spy. Now as they stand on the precipice of divorce, a simmering mixture of revulsion, self-loathing, and perverted affection boils over into public displays of madness and cruelty, exposing the inhuman, mutated hearts torn apart by mutual disgust.

Though its title might suggest otherwise, Possession eludes attempts to nail its maddening course of events down to conventional explanations of ghosts or demons. Even that unholy aberration which Anna nurtures in her home cannot take responsibility for the strange trance that compels her and Mark to dispassionately cut into their skin with an electric knife, or the fact that their son’s teacher Helen bears an unsettling resemblance to her. If we are to identify a single catalyst for this absurd state of affairs, then it comes from within the souls breaking the holy matrimony that they are sworn under, transgressing laws of nature, morality, and social convention to act on their ugliest impulses.

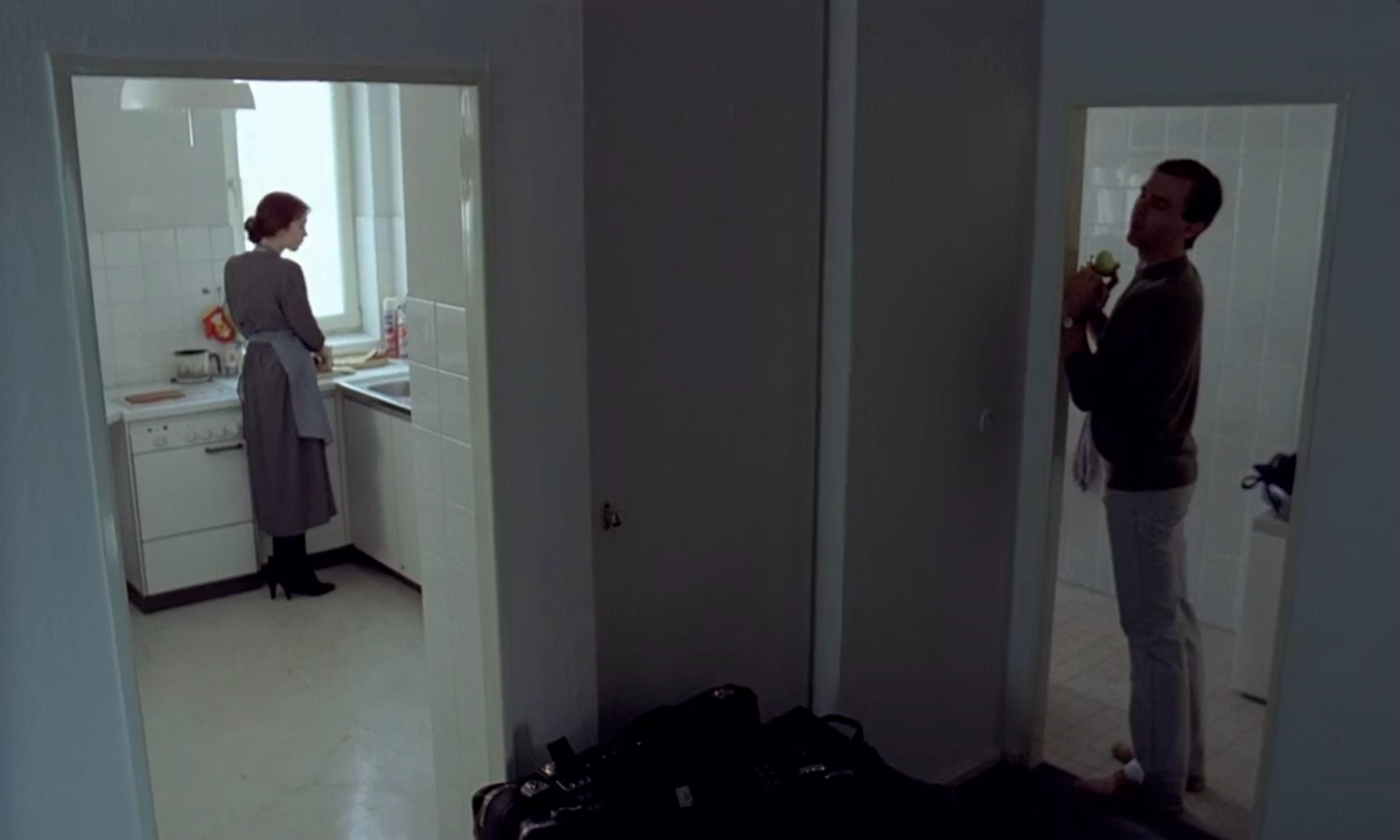

From a stylistic perspective, Andrzej Żuławski uses every cinematic tool at his disposal to attack the sanity keeping Anna and Mark tethered to reality. The camera’s restless momentum is the first thing to be noticed from the outset, drifting forward, backward, and around the couple’s public argument at a consistently steady pace like an active observer. It is a bold creative choice that formally resonates all throughout Possession, conveying a perpetual instability during Mark’s work meetings in vast, empty offices and later as he maniacally lights Anna’s apartment on fire. The creeping paranoia that it imbues in urban spaces points to Roman Polanski’s Apartment trilogy as a key influence here, and one which Żuławski continues to reflect in his tremendous blocking that frequently use hard lines and tiny frames in the mise-en-scène to split this divided couple.

Even Possession’s setting right by the Berlin Wall in the early 80s offers great symbolic significance of a city cleaved right down the middle, with both halves co-existing in a state of unresolved tension. Although Mark works as a spy for West Berlin, Żuławski is largely using the era’s politics as a backdrop to this story of two sides vying for control of each other, and even going so far as to seek out their idealised doppelgangers. For Anna, this looks like a calmer version of Mark who loyally grows under her guidance, while for Mark, he need look no further than Helen. Similarly played by Isabelle Adjani, her cool, composed demeanour and soft features appear in stark contrast to Anna’s incredible volatility, and she also proves to be a stronger maternal presence for Bob.

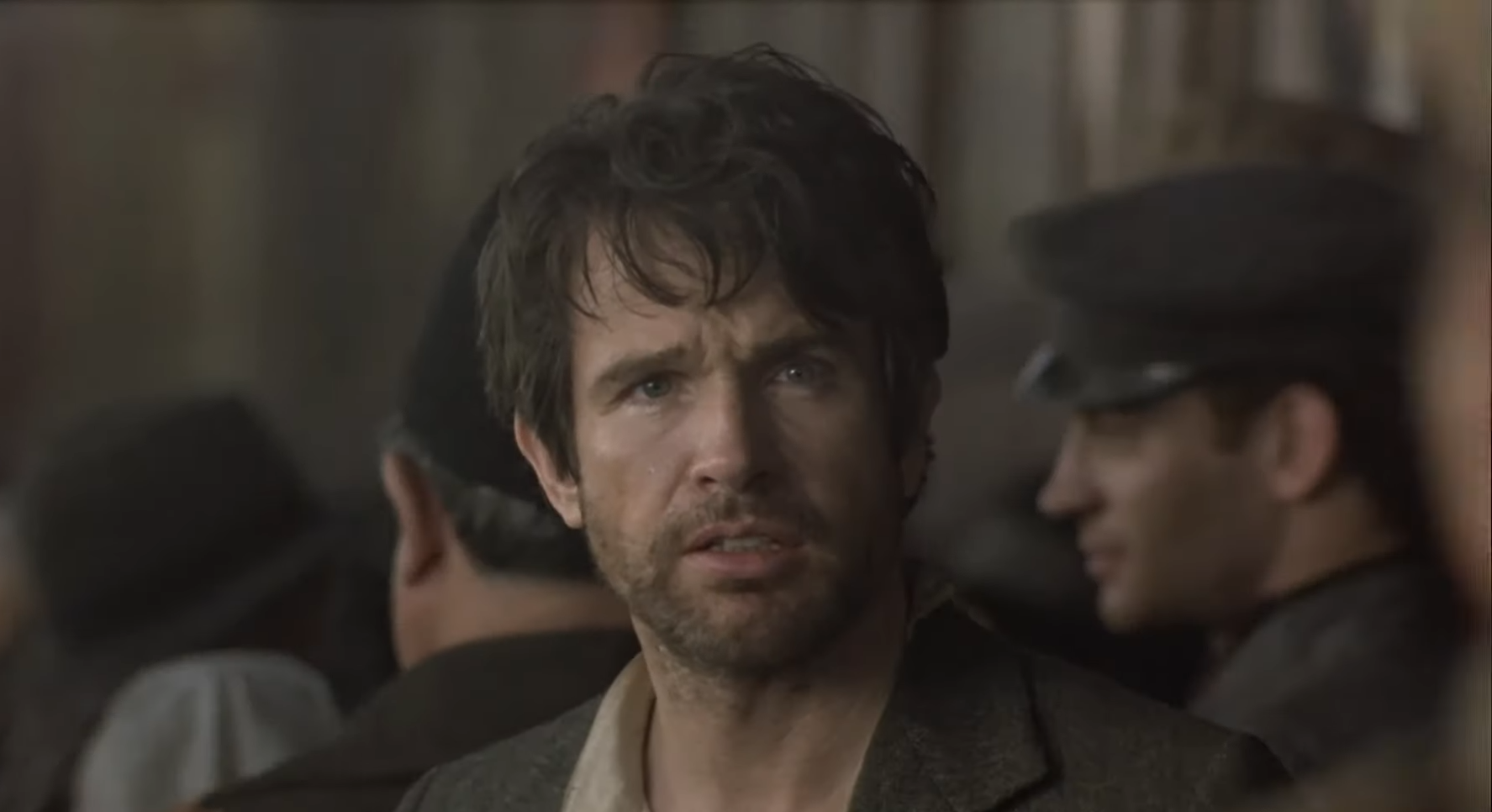

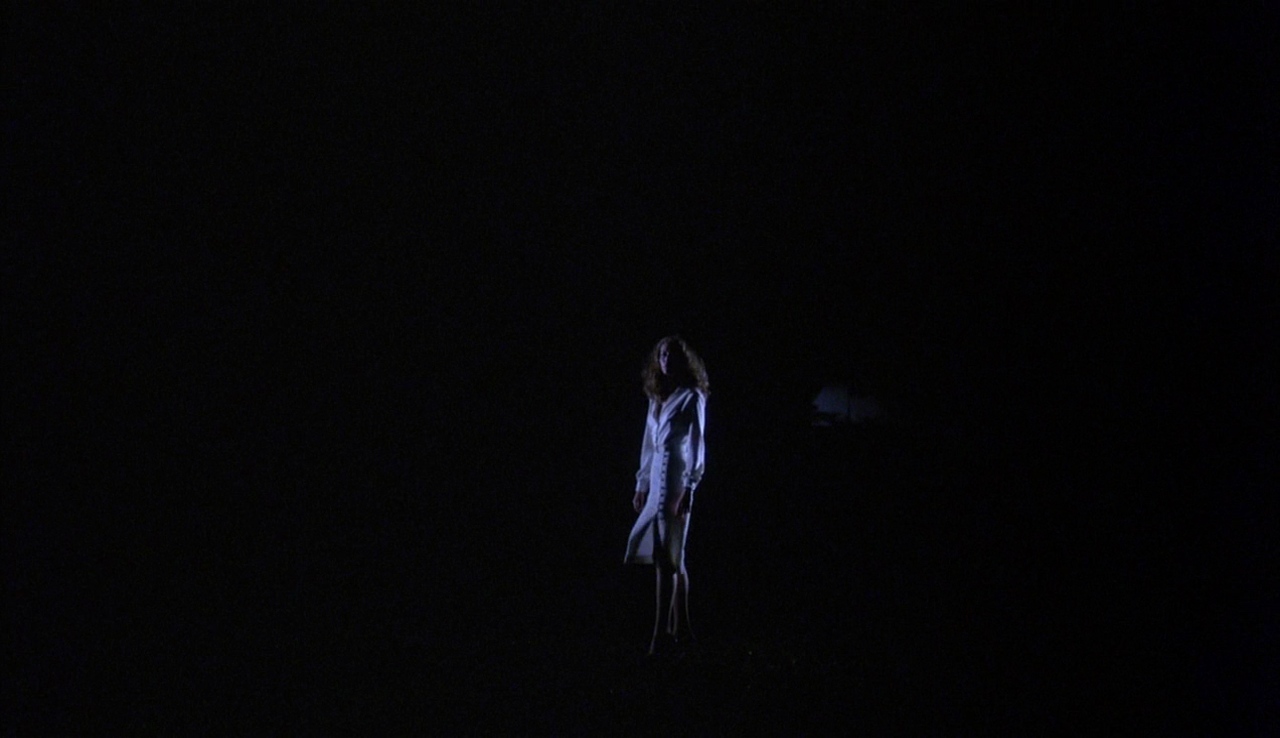

To call Adjani’s performance anything less than a landmark of film acting would be an understatement. Where Sam Neill frequently pushes for artificial swings of emotion, Adjani’s twitchy, erratic physicality seems to emanate from a primal subconscious, and yet she also demonstrates tremendous control when reigning herself in. Her outward expression of Anna’s mental state varies wildly between tumultuous breakdowns, disconnecting from the world at her quietest so that she doesn’t even notice a homeless man steal her groceries, and physically torturing one of her ballet students at her most sadistic. Żuławski’s close-ups wield enormous power in moments like these, catching her haunted, wide-eyed gaze that frequently drifts off into the distance, and elsewhere pierces the fourth wall with a malicious, demonic grin.

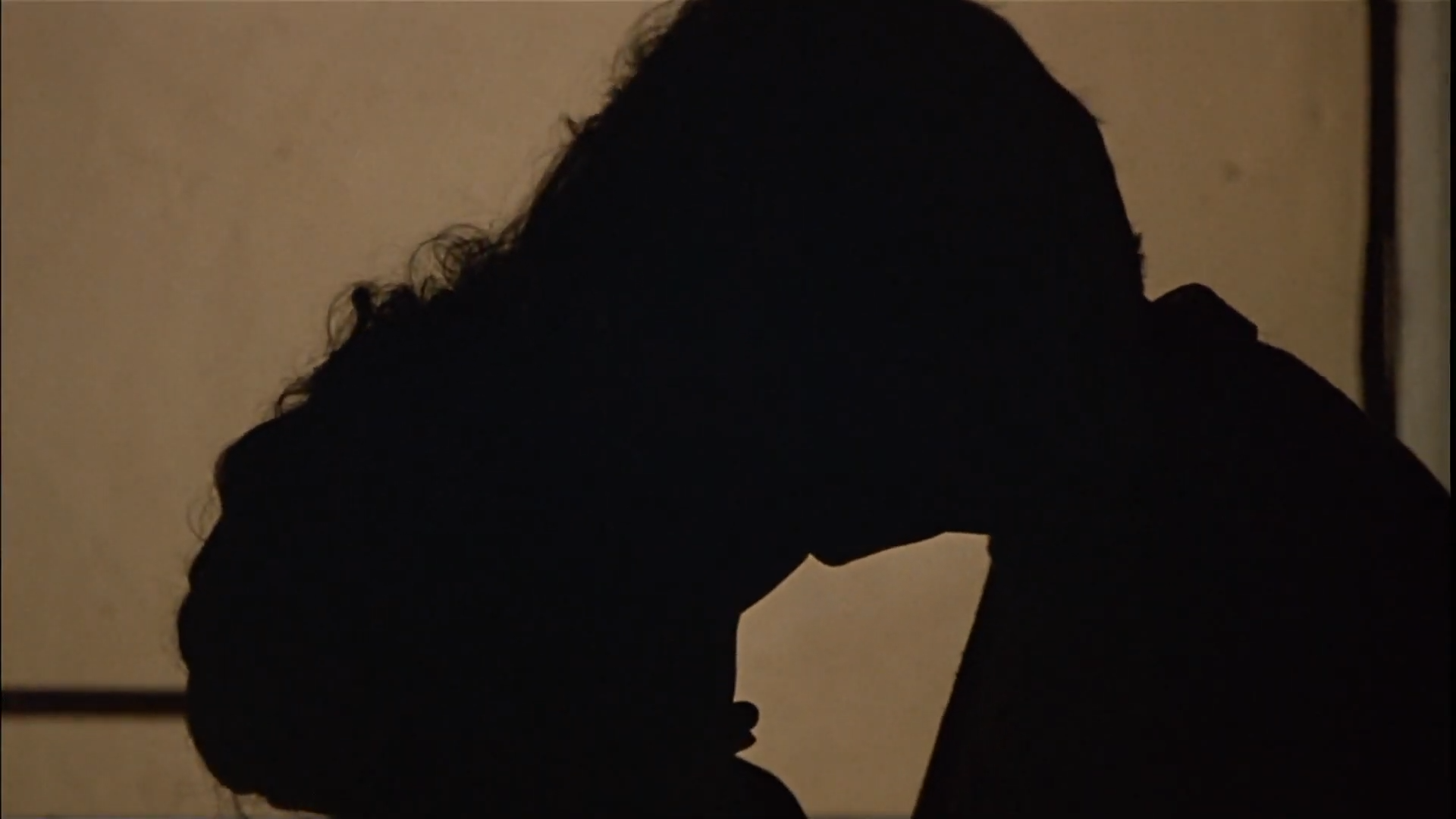

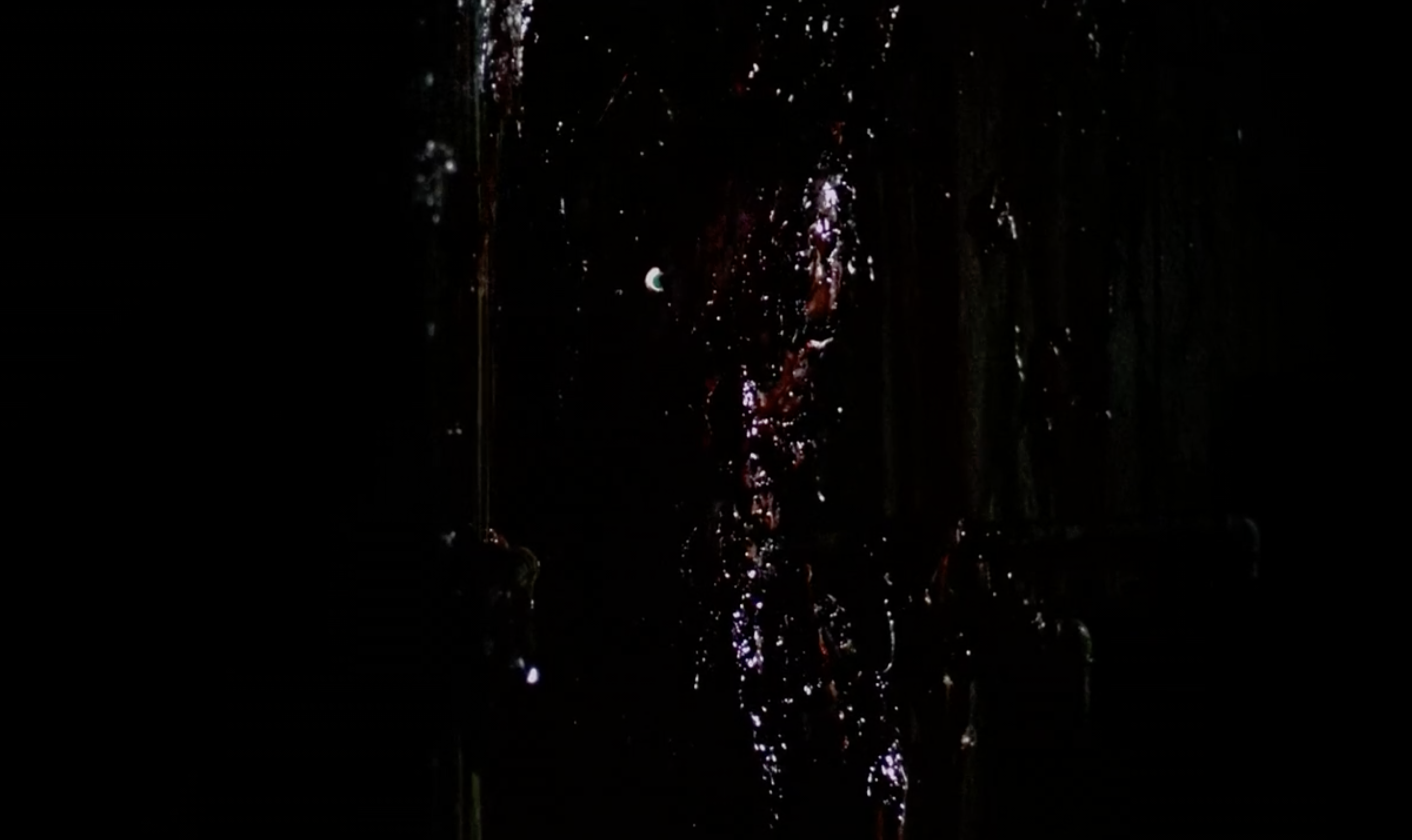

So ferociously uninhibited is Anna’s psychological disintegration that it is often hard to believe there is an actor inside that body. Comparisons to Gena Rowland’s harrowing depiction of mental illness in A Woman Under the Influence are well-earned as she tears at her hands and breaks out into panicked sweats, though Adjani’s physical performance takes up far more space in the frame, pairing especially well with Żuławski’s agitated tracking shots. We can’t quite tell at first what triggers her sudden unravelling in an empty subway station, though this is the scene that bears most resemblance to traditional possessions in horror movies, watching her scream in terror and violently throw her body around. She aggressively dashes her grocery bags against the wall until milk comes spilling out, yet still Żuławski’s camera continues orbiting her as deep, guttural gasps are forced from her throat. White fluids and blood pour from every orifice as she kneels on the ground, and it is finally at this point that we might start to recognise this as a truly hellish rendering of a miscarriage.

So explosive is Adjani’s embodiment of visceral suffering in Possession that it takes a little more straining to see the ruined world around her, mutating into an absurdist hellscape surrounding Anna and Mark’s bubble of hatred and co-dependency. Żuławski largely paints it out in drab, muted colours, only to rupture the monotony every now and again with a vibrant orange telephone or red train carriage, while the dissonant sounds of scratching, squeezing, and tapping infuse the heavily synthesised music score with an eerie practical quality. The murders that Anna commits barely go noticed for a long time, though given the strange behaviour of strangers who randomly chase people on the street and others who commit suicide with little warning, it would appear that such brutal insanity isn’t so out of place.

Whether through geopolitical, personal, or supernatural conflict, this world is ripping apart at the seams, yet still Mark and Anna try to force their arbitrary images of marital happiness through to the very end. Shot down by police and dying on a stairwell, their blood-soaked faces passionately kiss, while their apparently flawless doubles take their places as Bob’s new parents – though clearly not for long. Whether through murder, self-destruction, or the arrival of nuclear apocalypse, death eventually comes for all in Possession. In the end, Żuławski’s warring spouses only drive themselves mad with broken vows and hearts, feverishly seeking out a love that can’t even begin to thrive within such depraved, vile souls.

Possession is currently available to purchase on Blu-ray and DVD on Amazon.