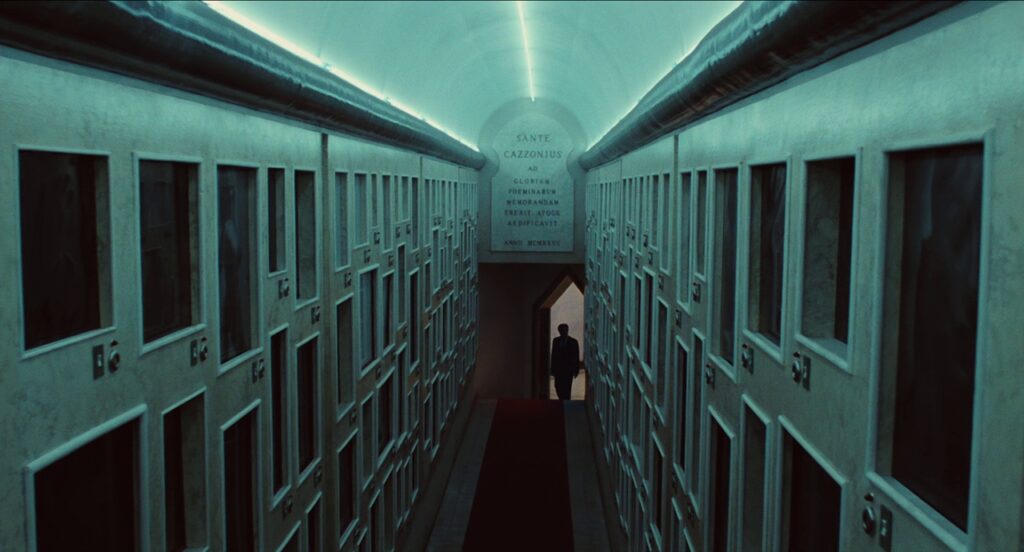

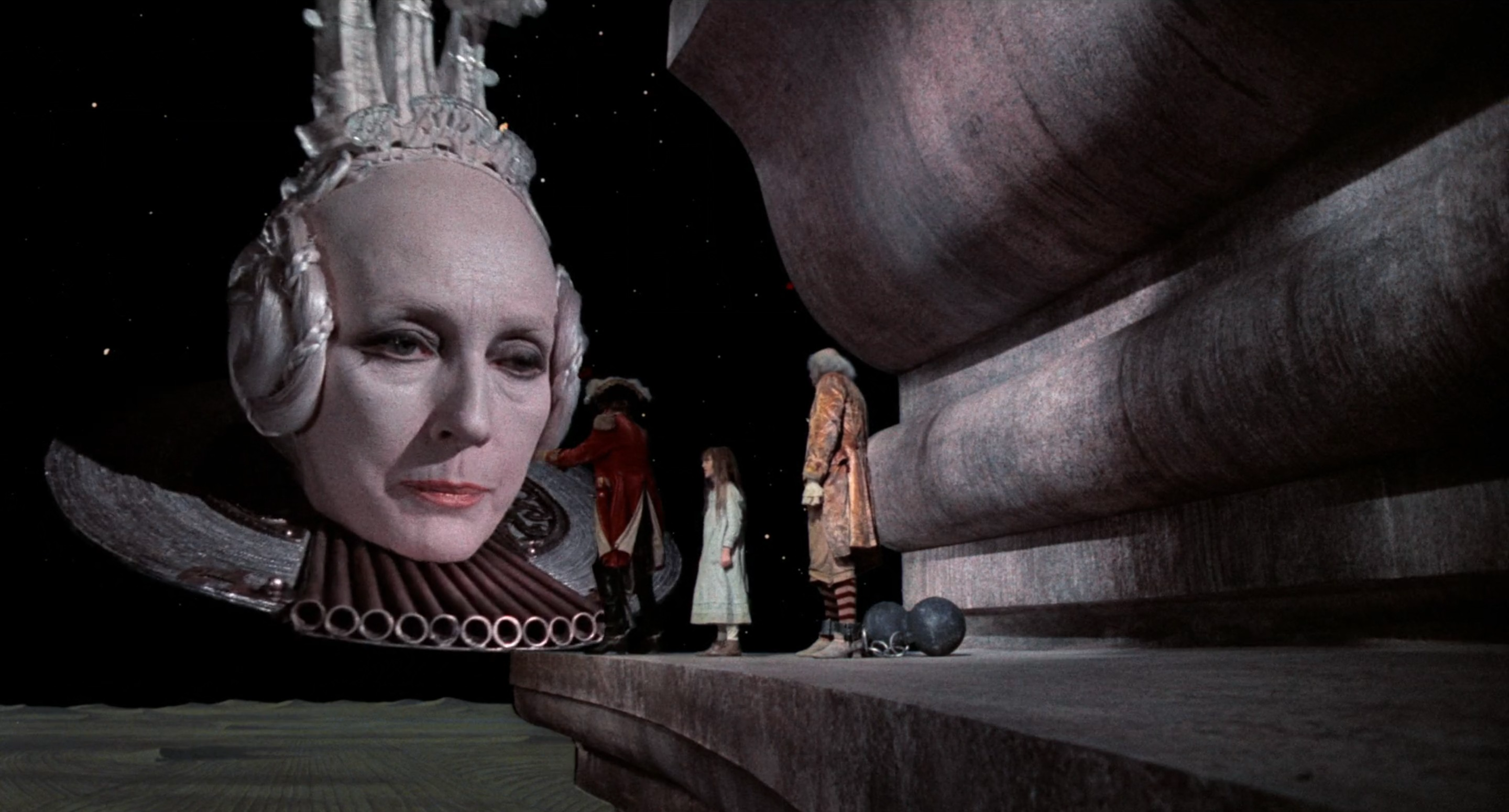

Cobra Verde (1987)

Cobra Verde may not be as tightly focused as Werner Herzog’s grander masterpieces, yet in this grotesque nightmare of one bandit’s mission to revive Western Africa’s slave trade, it brutally exposes the barbaric machinery of empires built on the systemic commodification of suffering.