Rainer Werner Fassbinder | 1hr 33min

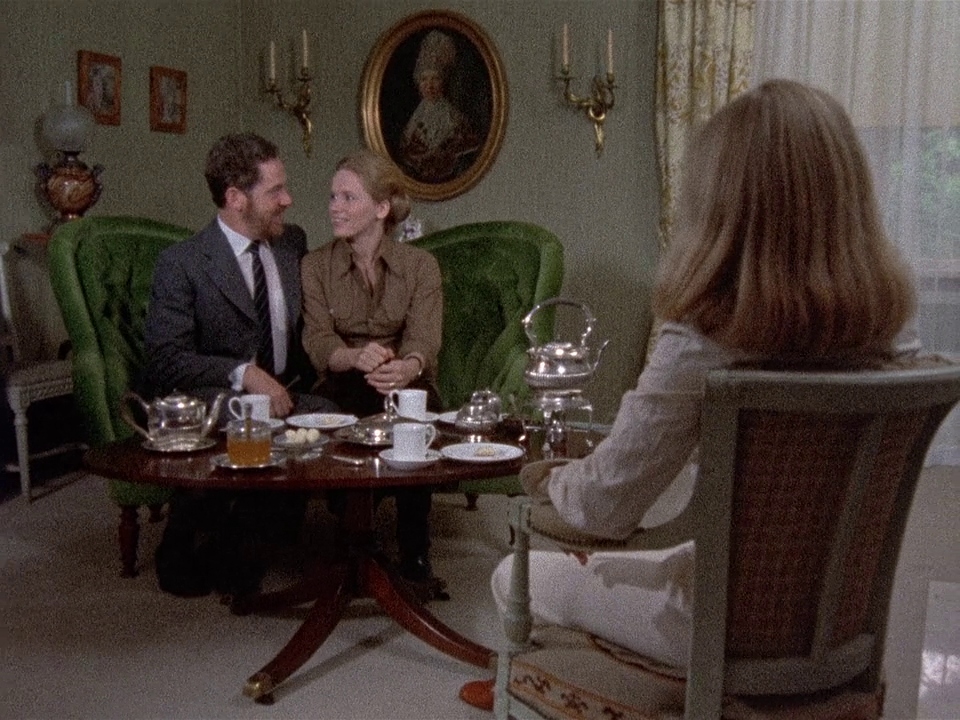

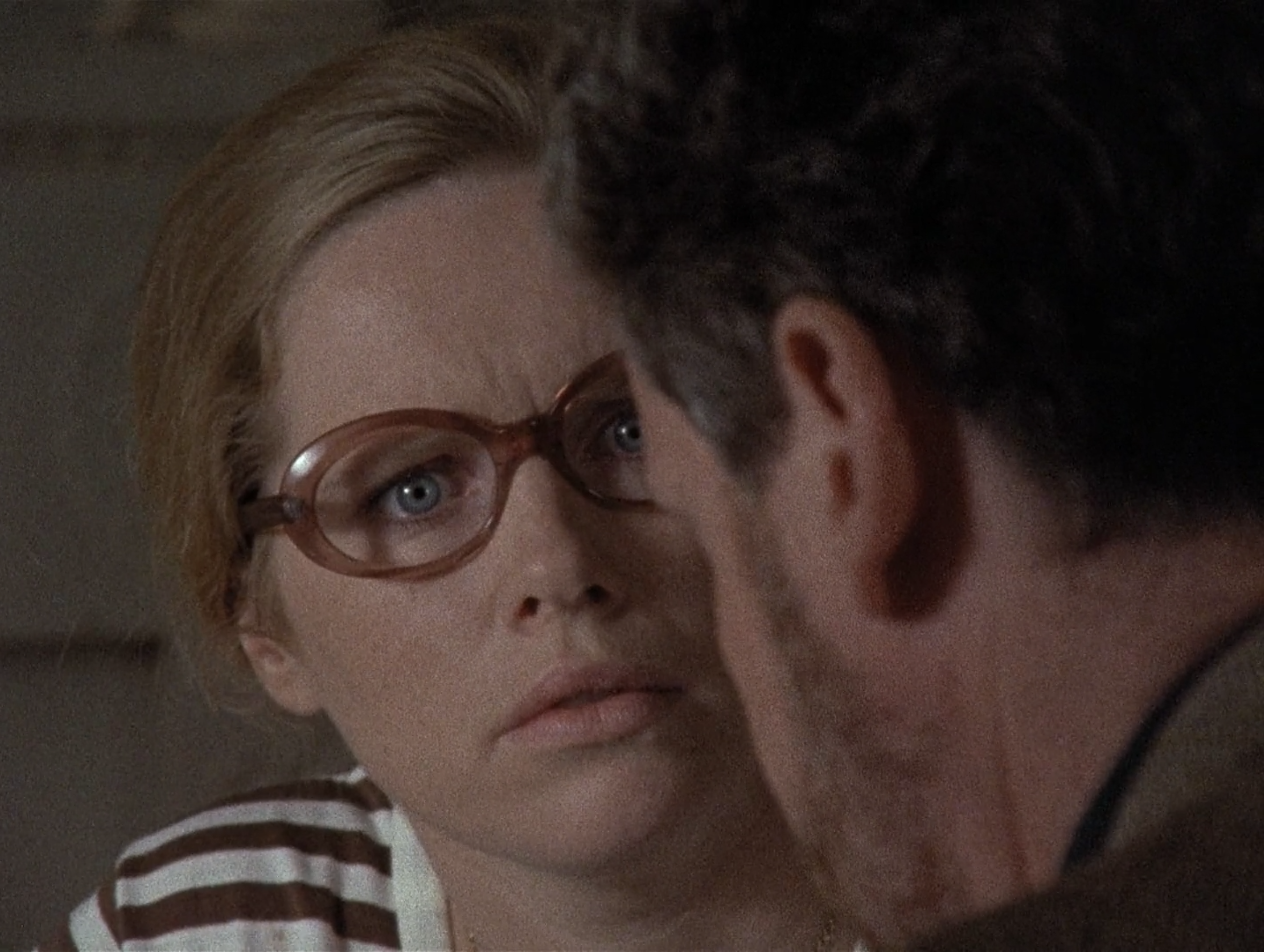

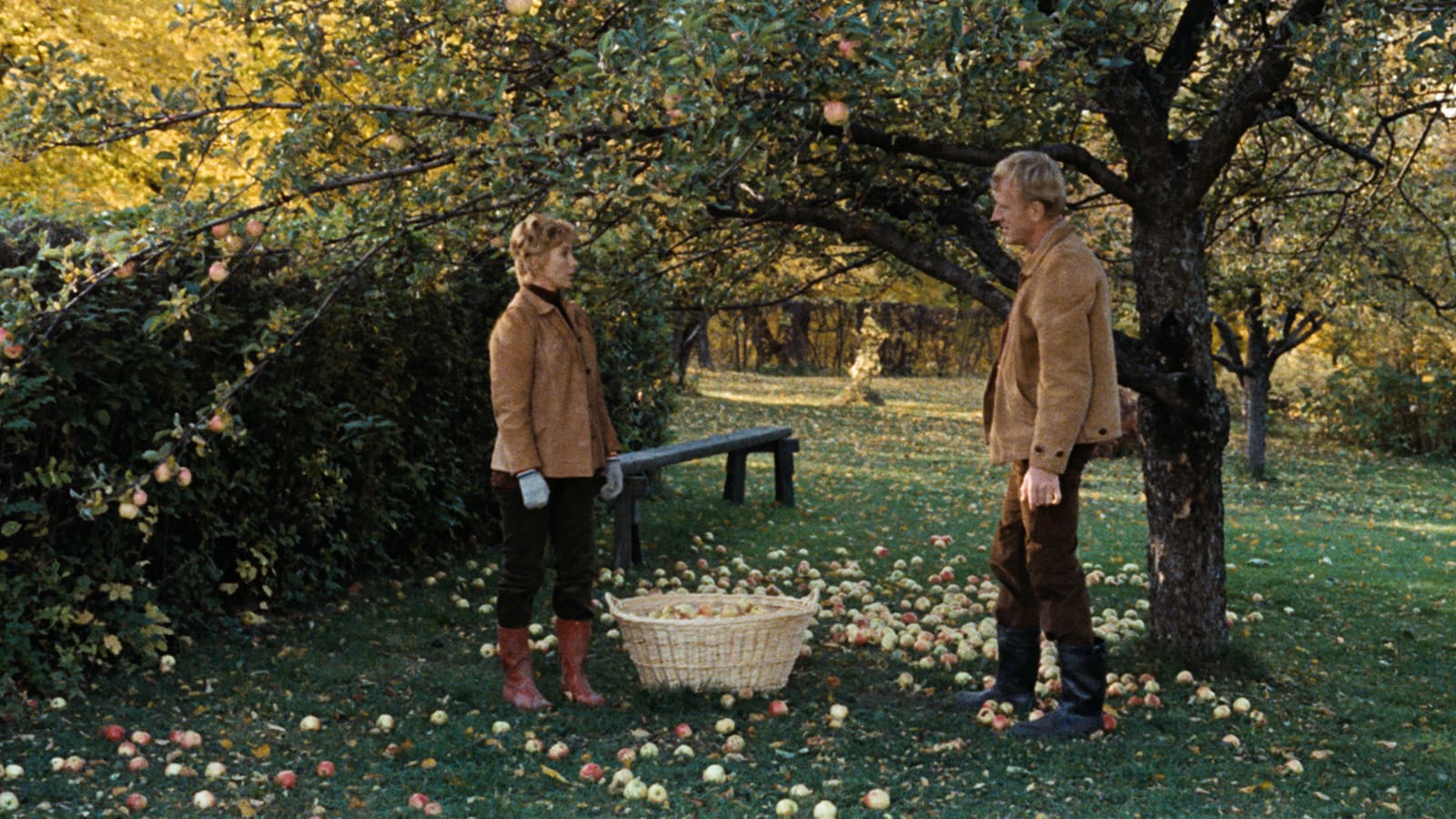

According to Emmi’s new lover, Ali, there is an old Arabic saying that warns against insecurity as the enemy of love, and which gives Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film its name. “Fear no good. Fear eat the soul up,” he warns her when she expresses anxiety around their blossoming relationship. This fear attacks from the inside, dissolving convictions which might have already weathered the worst of the world’s pressures, and yet which eventually crumble to pieces and turn lovers against each other. Then again, perhaps it is equally the result of a social prejudice which has become so normalised around them. Douglas Sirk’s 1950s American melodramas may be the primary source of Fassbinder’s influence, but Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is just as much a product of cultural tensions in 1970s Germany, pushing the transgressive love between a middle-aged woman and young man in All That Heaven Allows even further with an interracial romance.

When Emmi and Ali first meet, they are living in the shadow of the 1972 Munich Massacre, where eight Palestinian terrorists kidnapped and kill several members of the Israeli Olympic team. On top of this, Emmi acknowledges her own family’s involvement in the Nazi party, with her late father being particularly xenophobic. This nation’s shameful history lives on in recent memory for many citizens, becoming such a part of everyday life that its true horror is easily trivialised. When Emmi takes Ali out to a fancy restaurant she has always wanted to try, the fact that it used to be Hitler’s favourite restaurant is given no more than a passing mention, and it is also no odd occurrence for racial slurs to be casually thrown at those with skin tones similar to those of the Olympic terrorists.

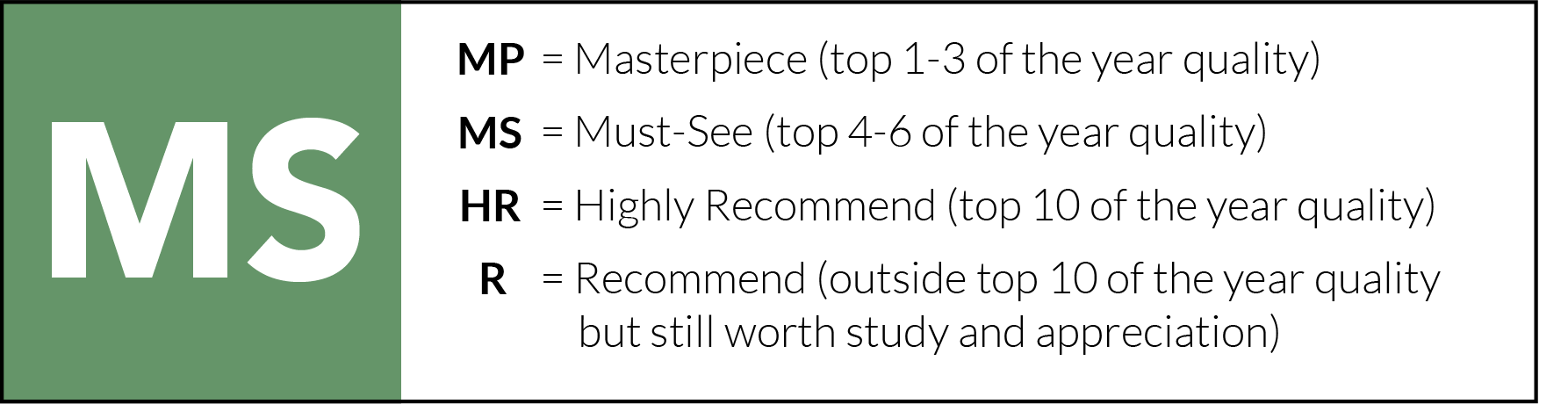

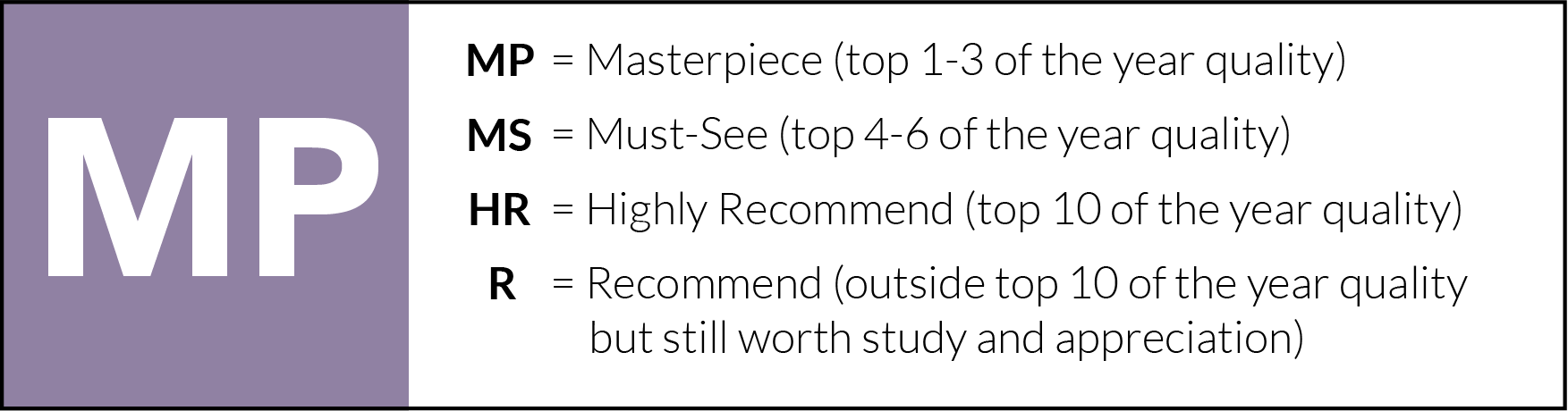

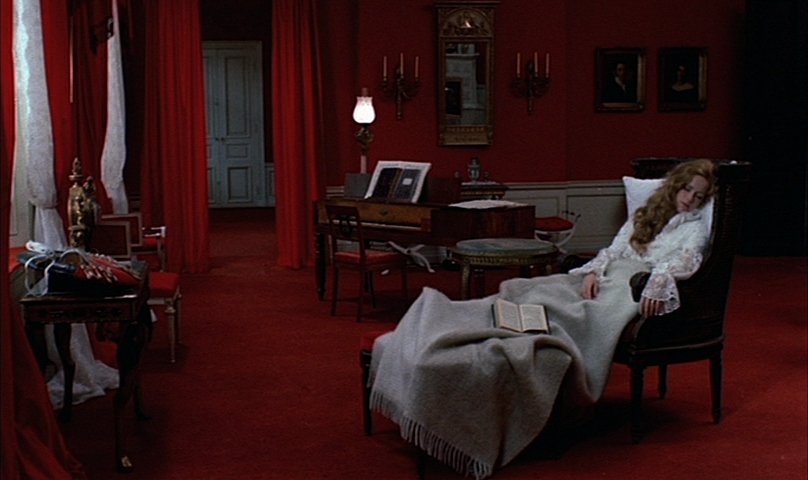

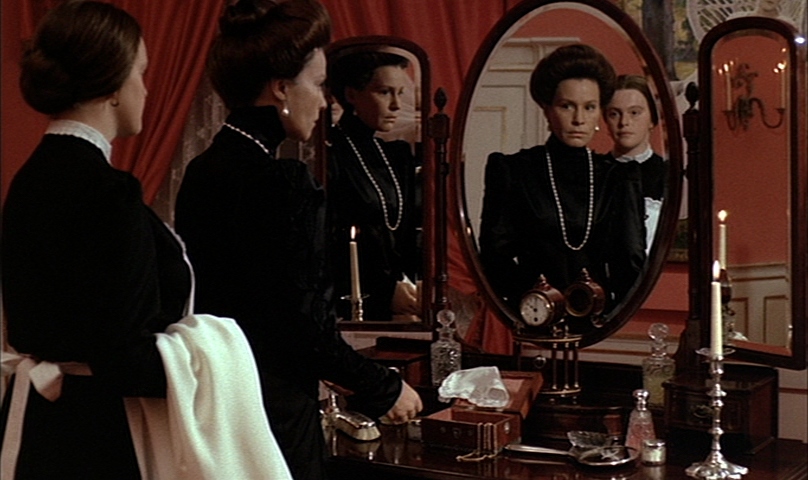

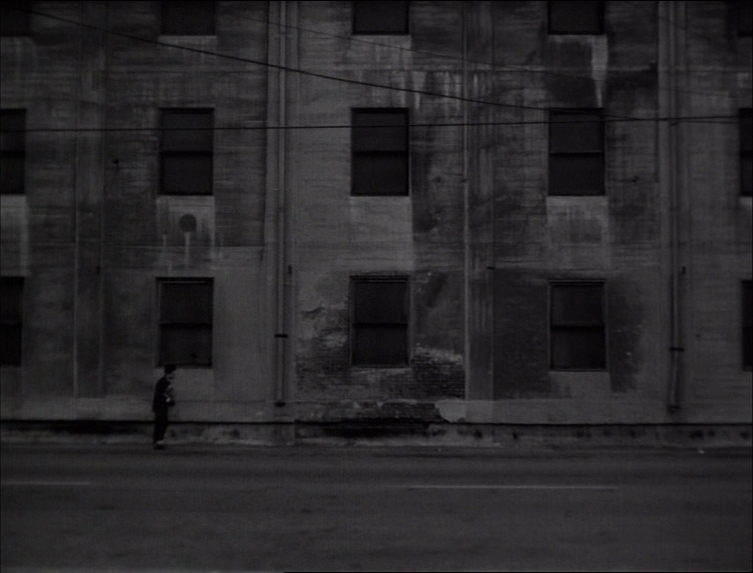

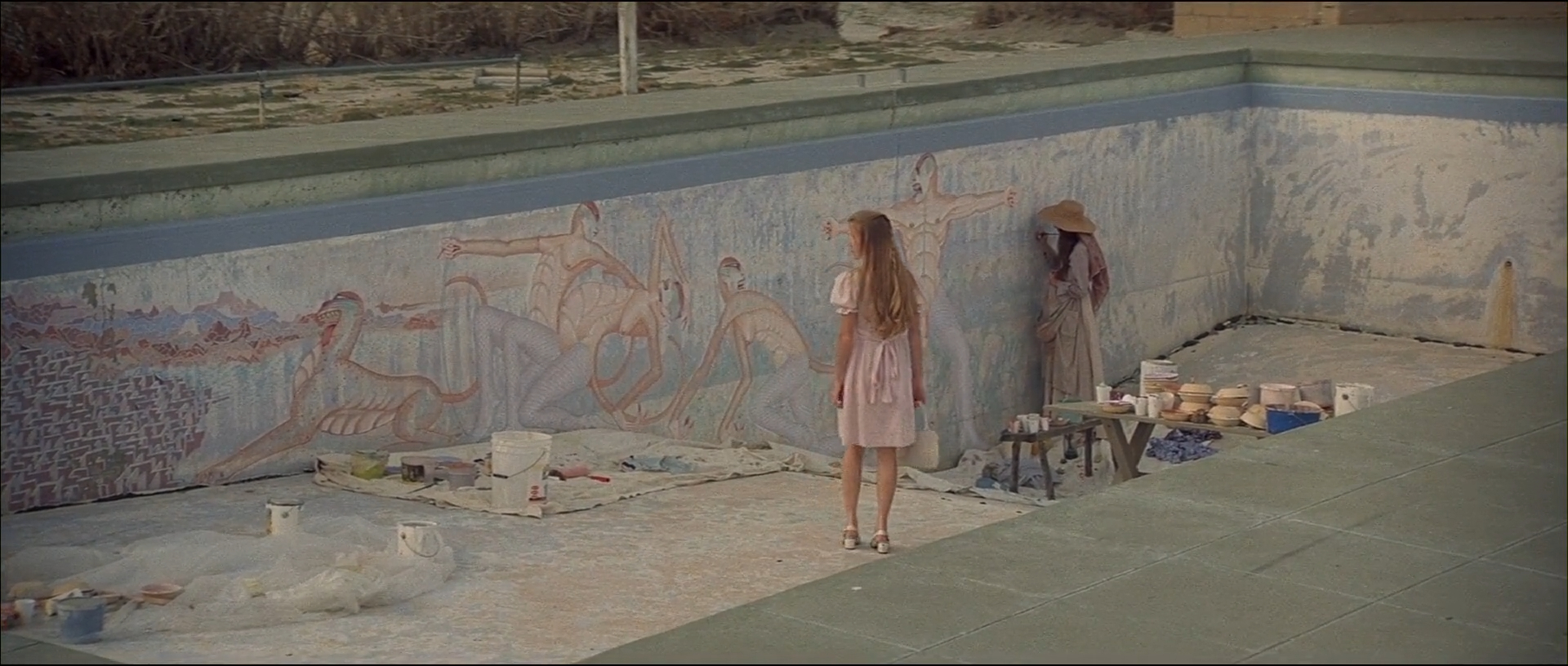

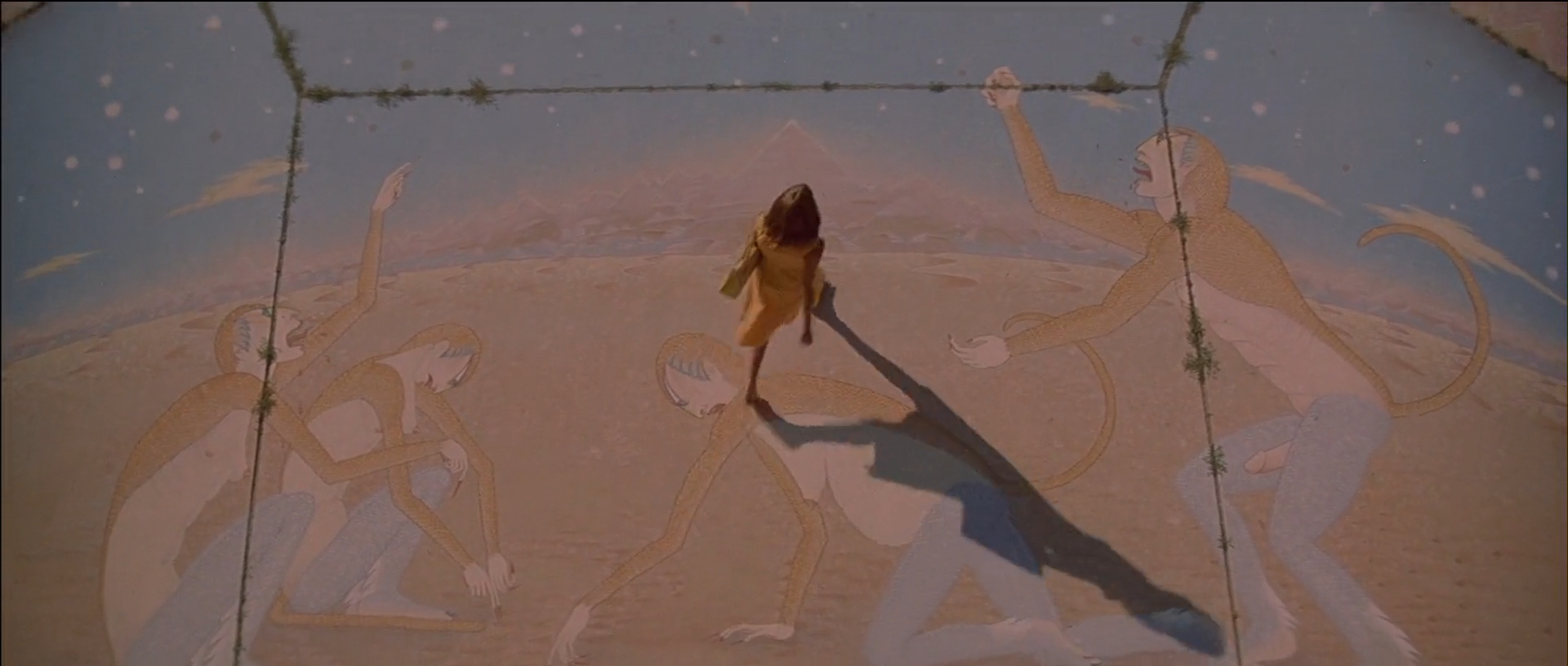

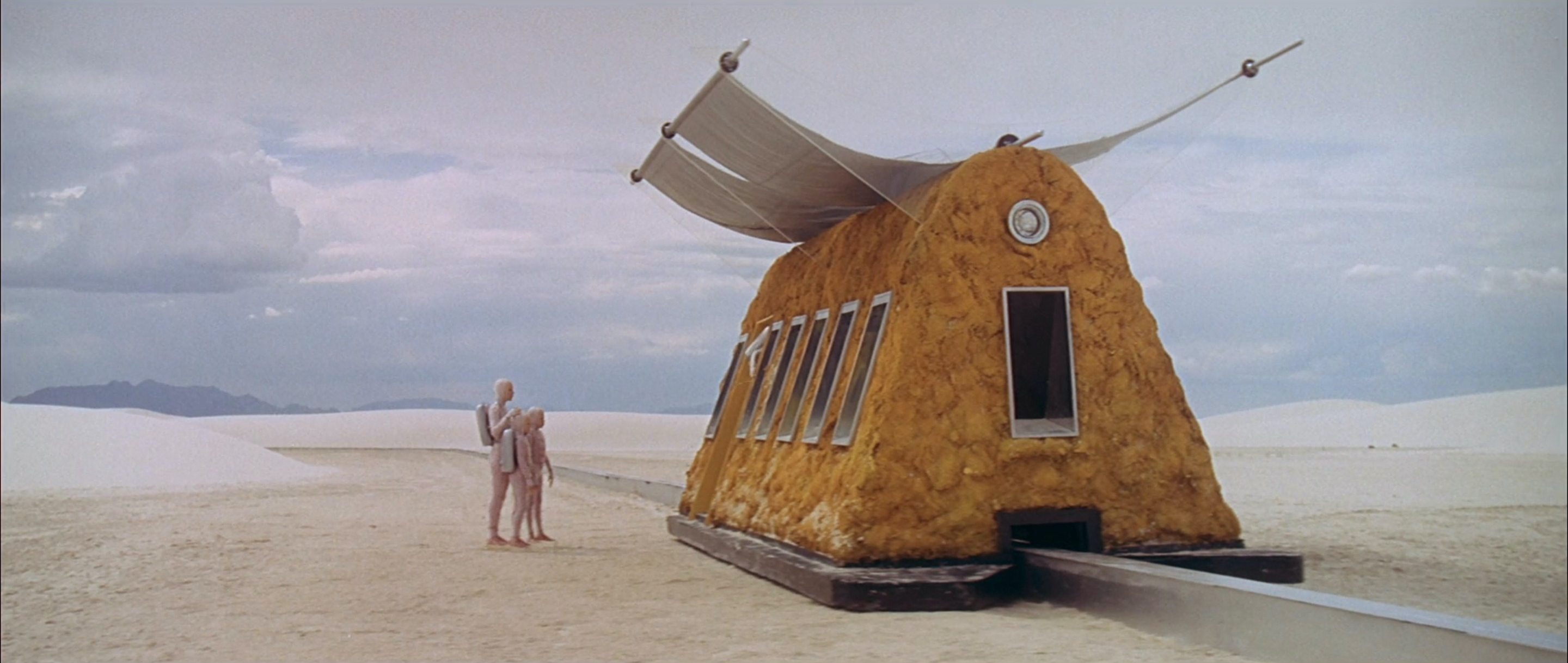

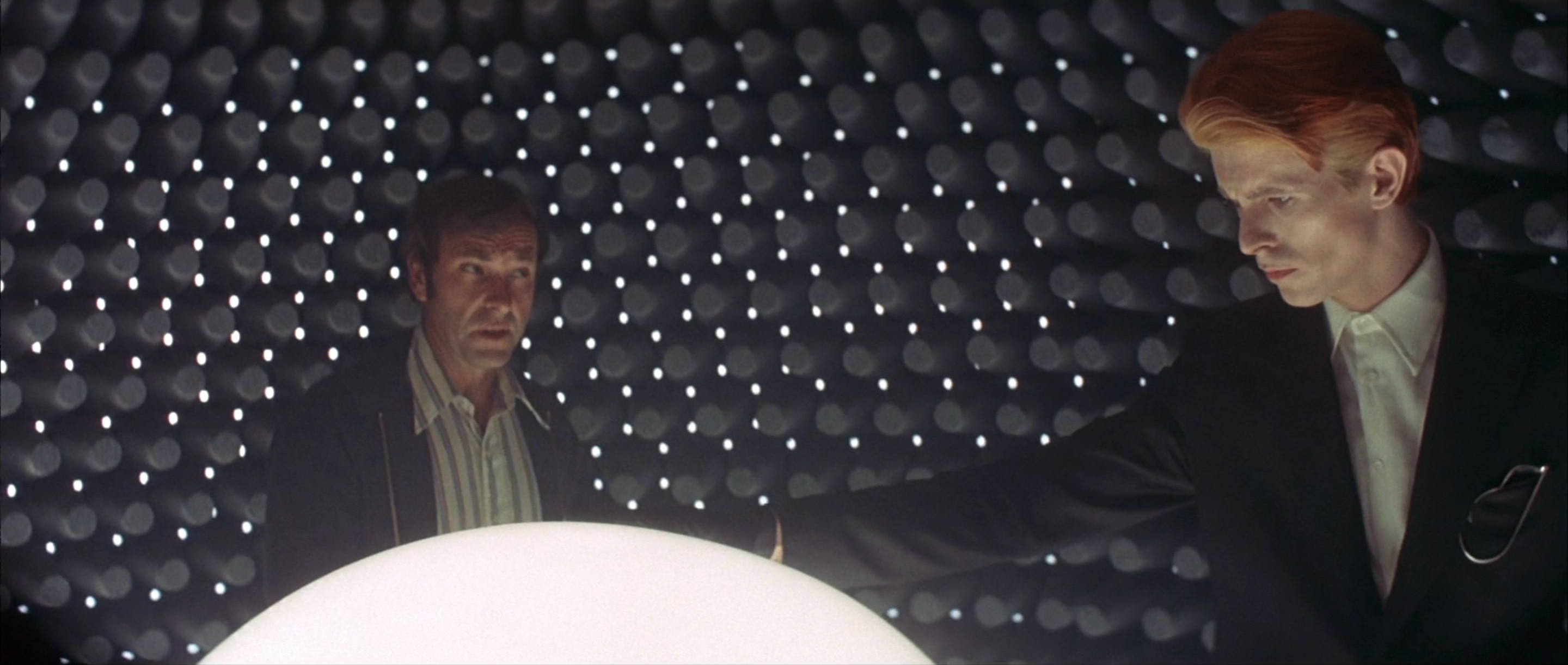

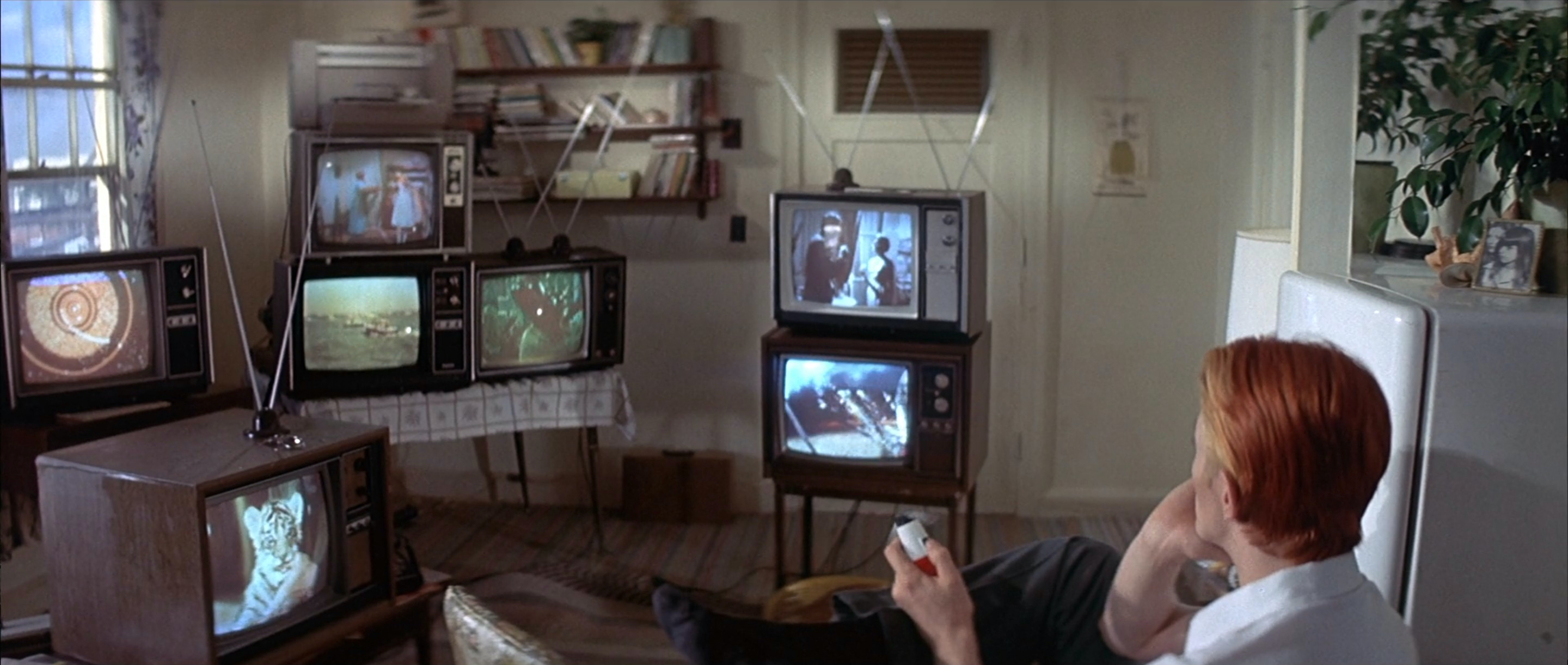

In Fassbinder’s visuals as well, modernity hems his characters into tight corners, doorframes, archways, and narrow corridors. Many of these are as drably unadorned as the architecture lining Munich’s streets, bearing the discoloured marks of erosion and suffusing his aesthetic with an element of realism that was never present in Sirk’s highly stylised studio sets. At the same time though, Fassbinder does not resist injecting his mise-en-scène with warm bursts of blazing colour when a scene calls for it, painting the walls of Emmi’s home canary yellow and framing her between crimson drapes. In the bar where she first meets and dances with Ali right at the start of the film too, Fassbinder sheds a vibrant red light over them, saturating them in the passion of their mutual attraction and separating them from the dreariness of the outside world.

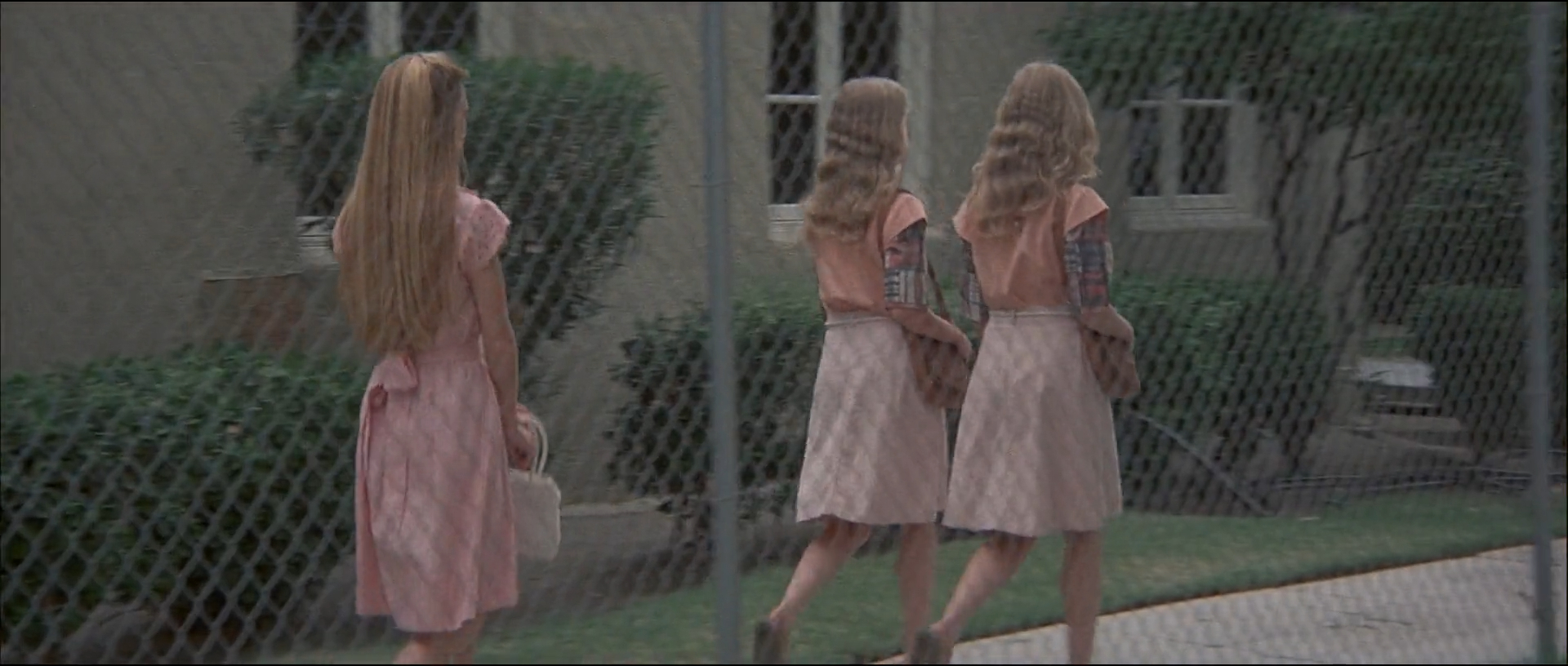

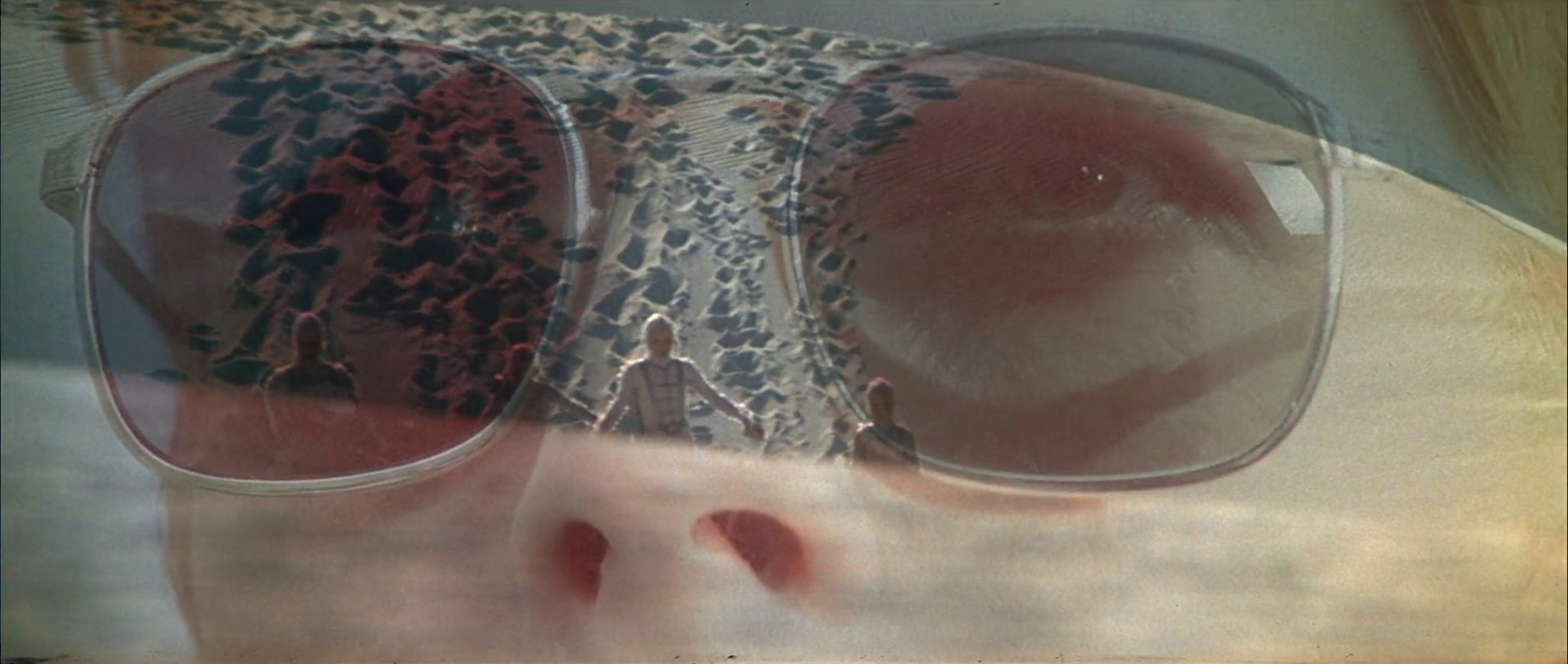

The greatest visual motif of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul though comes in Fassbinder’s constant return to the worn-out, winding stairwell of Emmi’s apartment building, where she sits with her neighbours and listens to their petty gossip. With Fassbinder using its uneven levels, cramped space, and wooden banister to visually isolate her, she doesn’t appear to be particularly comfortable here, and it certainly doesn’t help that these women are some of the most racist critics of her relationship with Ali. Within these uncomfortable conversations and behind these railings, she is completely trapped, confined to a liminal space between domestic and public life that refuses to separate one from the other.

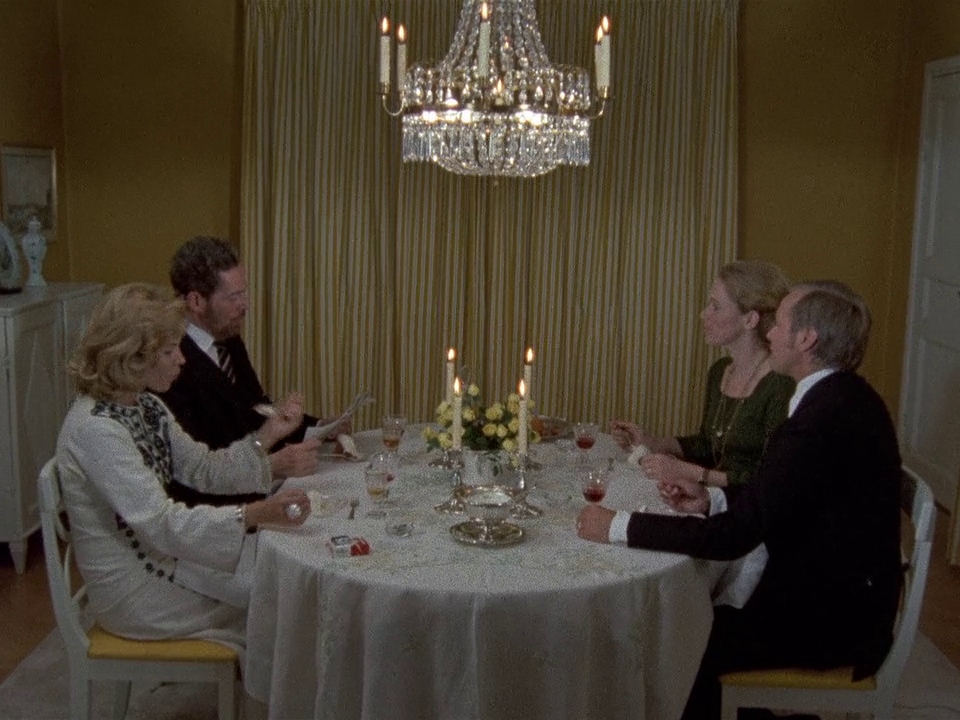

In the movements of Fassbinder’s camera too, we often find a sharp elegance to its tracking shots, often choosing to shift into new compositions rather than cut, as we observe in the slow pan across the disgusted faces of Emmi’s children when they meet her new partner for the first time. This also ties into the larger tension at play between his melodrama and social realism, intoxicating us with his lush visual style, and then breaking it up with prickly reminders of 1970s Germany’s horrific racial intolerance.

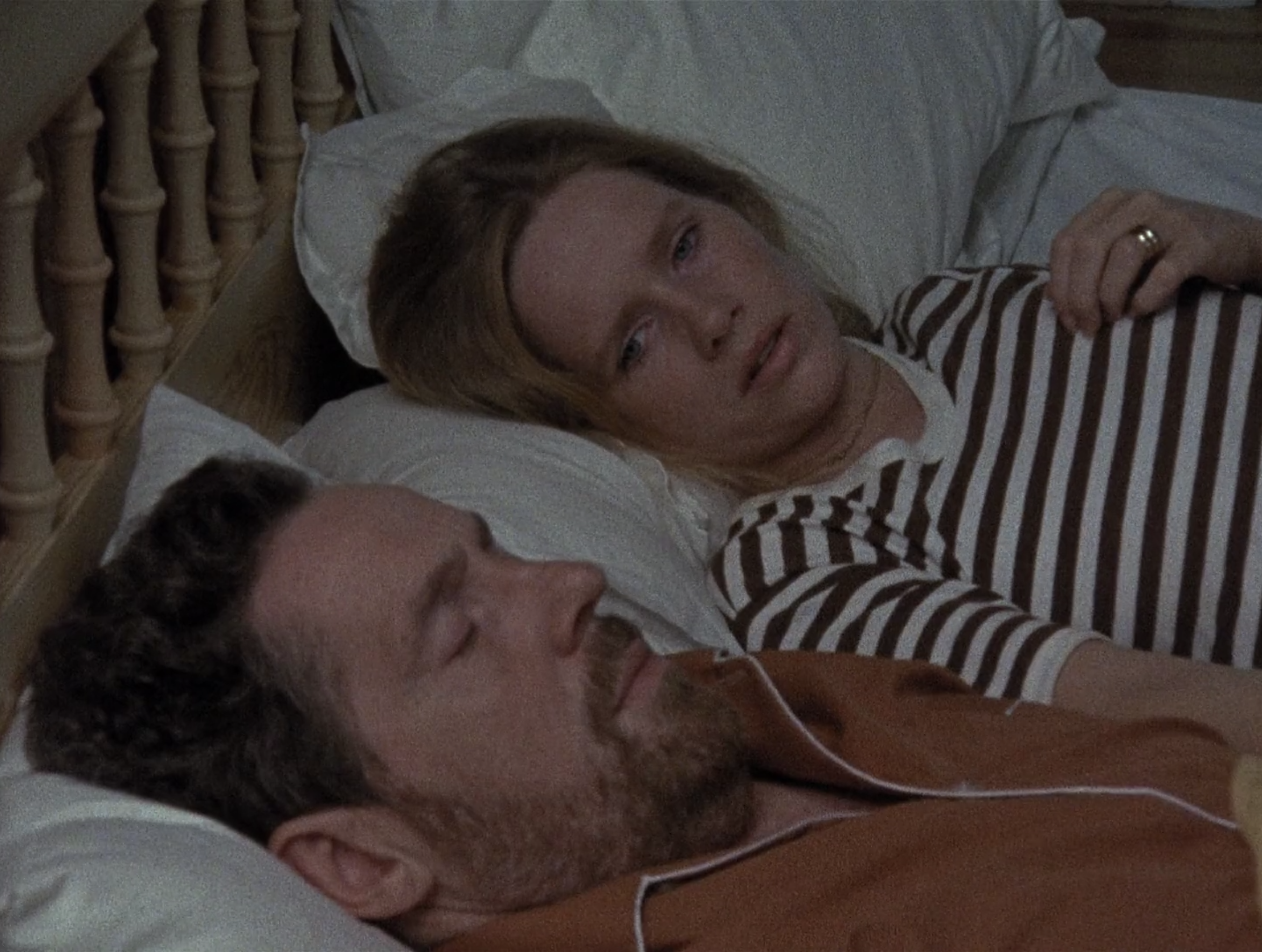

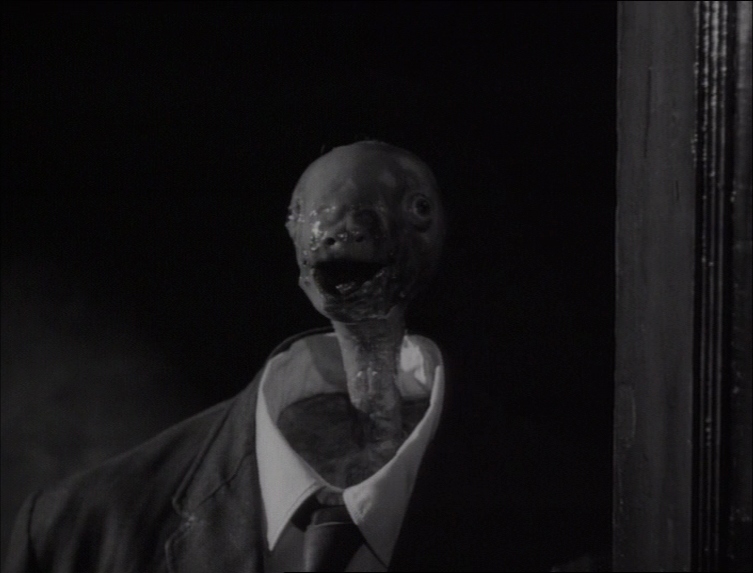

That Emmi begins to adopt elements of that prejudice is all the more tragic, as Fassbinder pushes the All That Heaven Allows-inspired romance another step further with both lovers subconsciously internalising their harshest criticisms. From Emmi’s desire to return to a quieter, more traditional life comes her demand for Ali to stop eating couscous, while her objectification of his body in front of her friends exposes a racial fetishism even more insidiously ingrained in her social conditioning. Both look smaller than ever in Fassbinder’s narrowed frames as distances between them grow wider, leaving Ali to seek comfort outside the bonds of marriage with an old girlfriend.

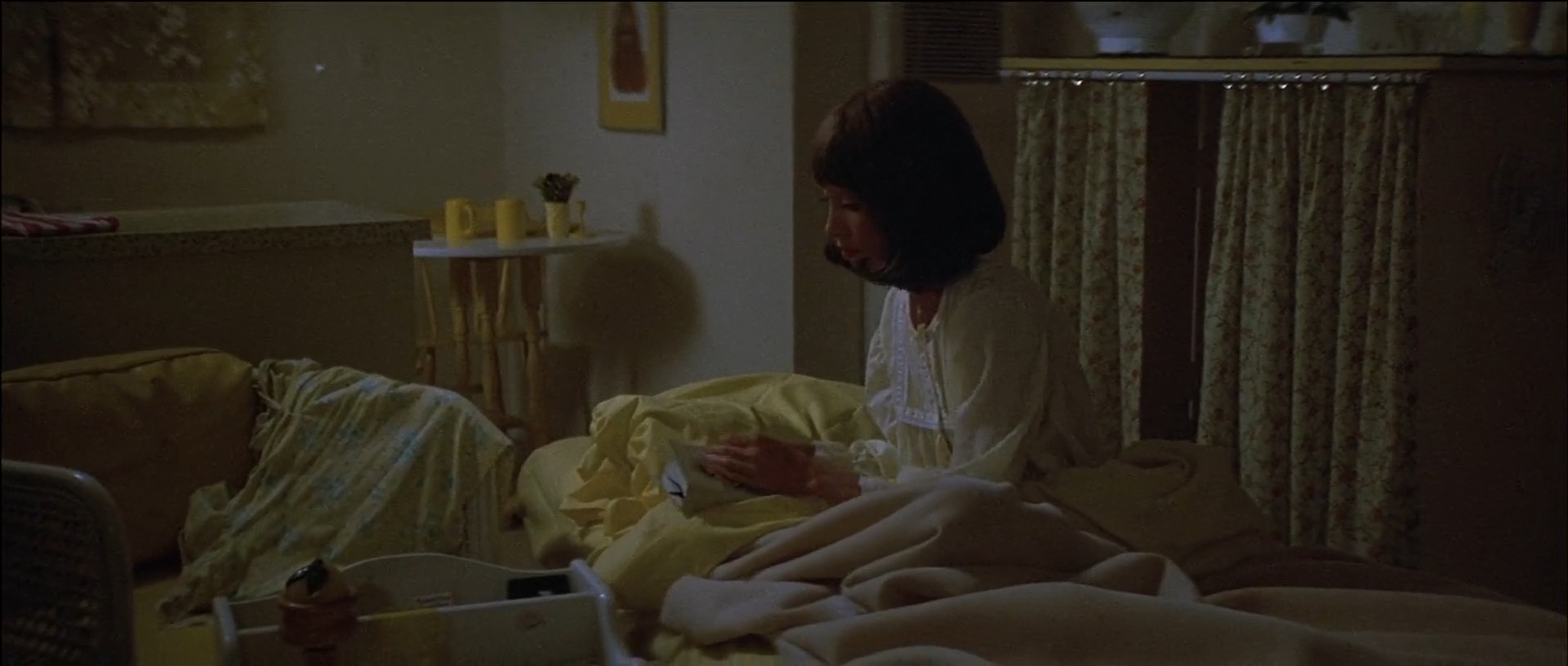

At least while these lovers were at their most devoted, they would fight back against unwelcome insults, so it is entirely heartbreaking now to see them let such comments slide by with little resistance. A genuine attempt to reconcile their misgivings as they dance together in the bar where they met tragically comes far too late – Ali suddenly collapses without warning as Emmi holds him in her arms, and is promptly diagnosed with a type of burst stomach ulcer that often comes about from undue stress among immigrants.

It might be unlikely that Emmi was a direct cause of Ali’s illness, but the possibility also can’t be written off, and thus his earlier warning of fear eating the soul is reframed as a devastating prophecy. With this symbolic turn of fate, both the melodrama and realism of Fassbinder’s interracial romance finally merge into something even grander that transcends the sum of both – an ineffable moral fable of love’s greatest weakness and persistent strength.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.