Federico Fellini | 2hr 8min

The two eras of Rome that Federico Fellini displays in his offbeat homage to the Italian city are set apart by three decades, though the boundaries separating one from the other aren’t always so clearly outlined. Hippies lounge around ancient monuments in the 1970s, air raids send civilians running for cover in the 1940s, and yet still life goes on for those who seek the simple pleasures of sex, entertainment, and good food. After all, what else is there to cling to in a world eternally bound within a state of perpetual chaos?

This is not quite the Rome chronicled in history books, nor the Rome captured with authenticity in the films of the Italian neorealists. This is Fellini’s Roma – an absurd, urban landscape defined more by its culture, politics, and traditions than any individual icon. Not to say that Fellini’s film lacks idiosyncratic characters – in fact virtually everyone here sets themselves apart from the colourful crowd – but they are simply threads woven into a larger, vibrant tapestry. Despite its familiar interrogations of modern Rome’s debauchery, Roma bears far greater resemblance to the surreal, episodic madness of Fellini Satyricon than the focused character study of La Dolce Vita. Such a grandiose defiance of narrative convention comes with some structural unevenness, though Fellini’s recreation of the city he both loathes and adores is nonetheless rich with impressionistic detail, filtering moments in time through the wily incongruity of satire and memory.

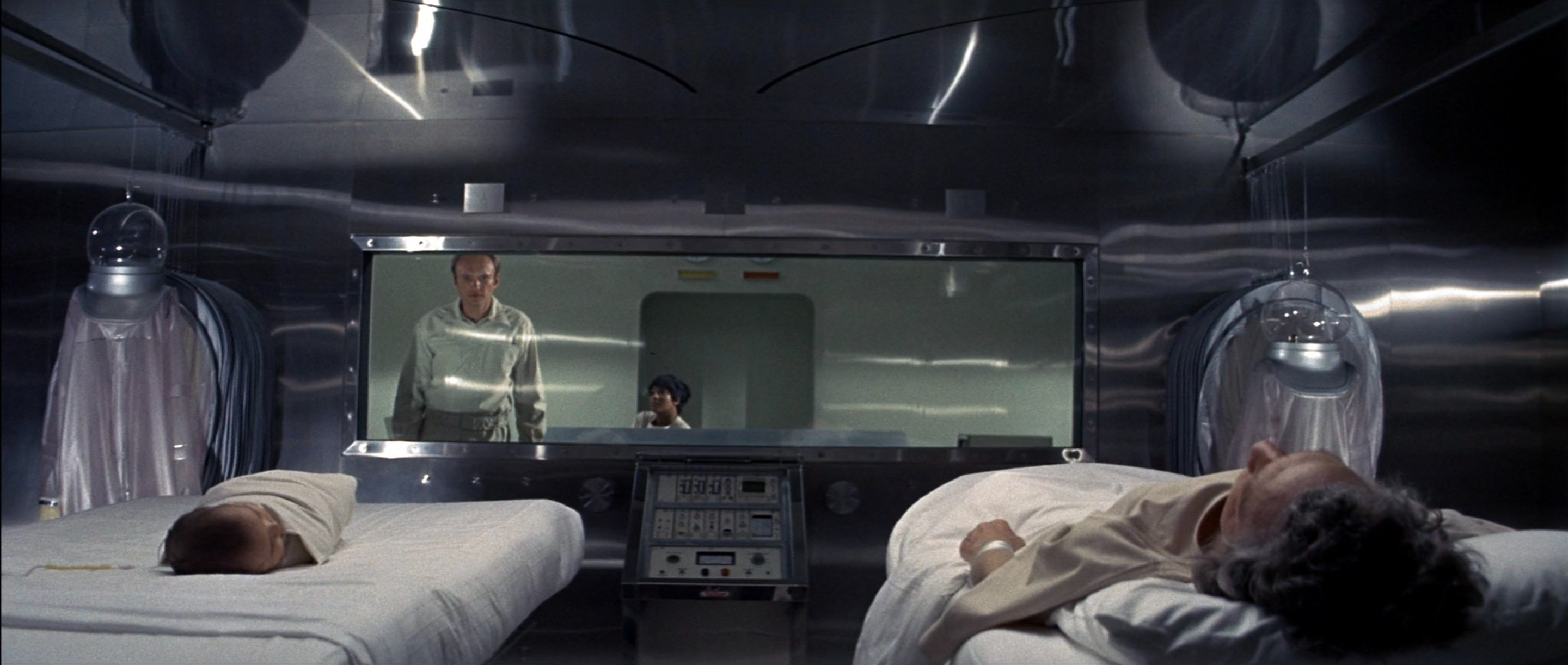

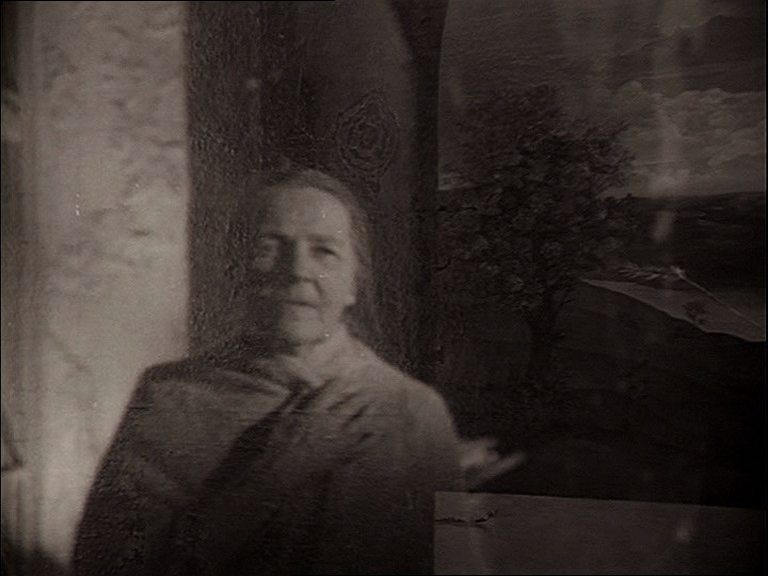

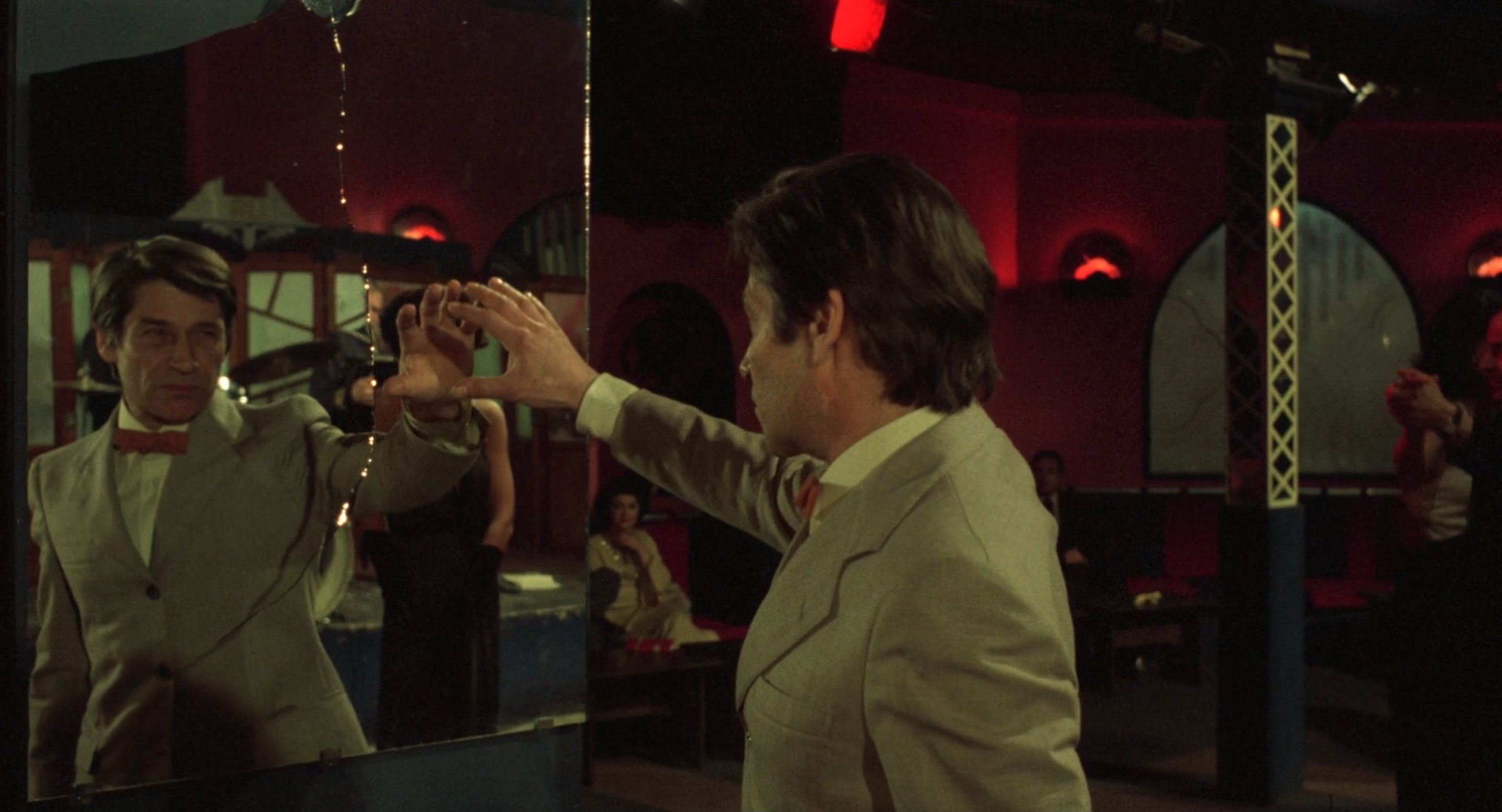

If there is a consistent character in Roma whom we are to follow beyond Rome itself, then it is the strange presence of Fellini himself in two forms. The first is a semi-autobiographical representation of the director watching silent films about Ancient Rome as a child, and later moving to the Nazi-occupied city as a young man. The camera moves with him past magnificent fountains and cathedrals in travelogue-style tracking shots, before he finally finds lodging at a shabby guesthouse bustling with vain actors, rowdy children, and religious zealots. The insanity seemingly has no boundaries, populating the streets at night with noisy al fresco restaurant patrons, and still we continue weaving through the crowd as our attention jumps from a waiter carrying a plate of pasta to the young Fellini being invited to eat with friendly strangers.

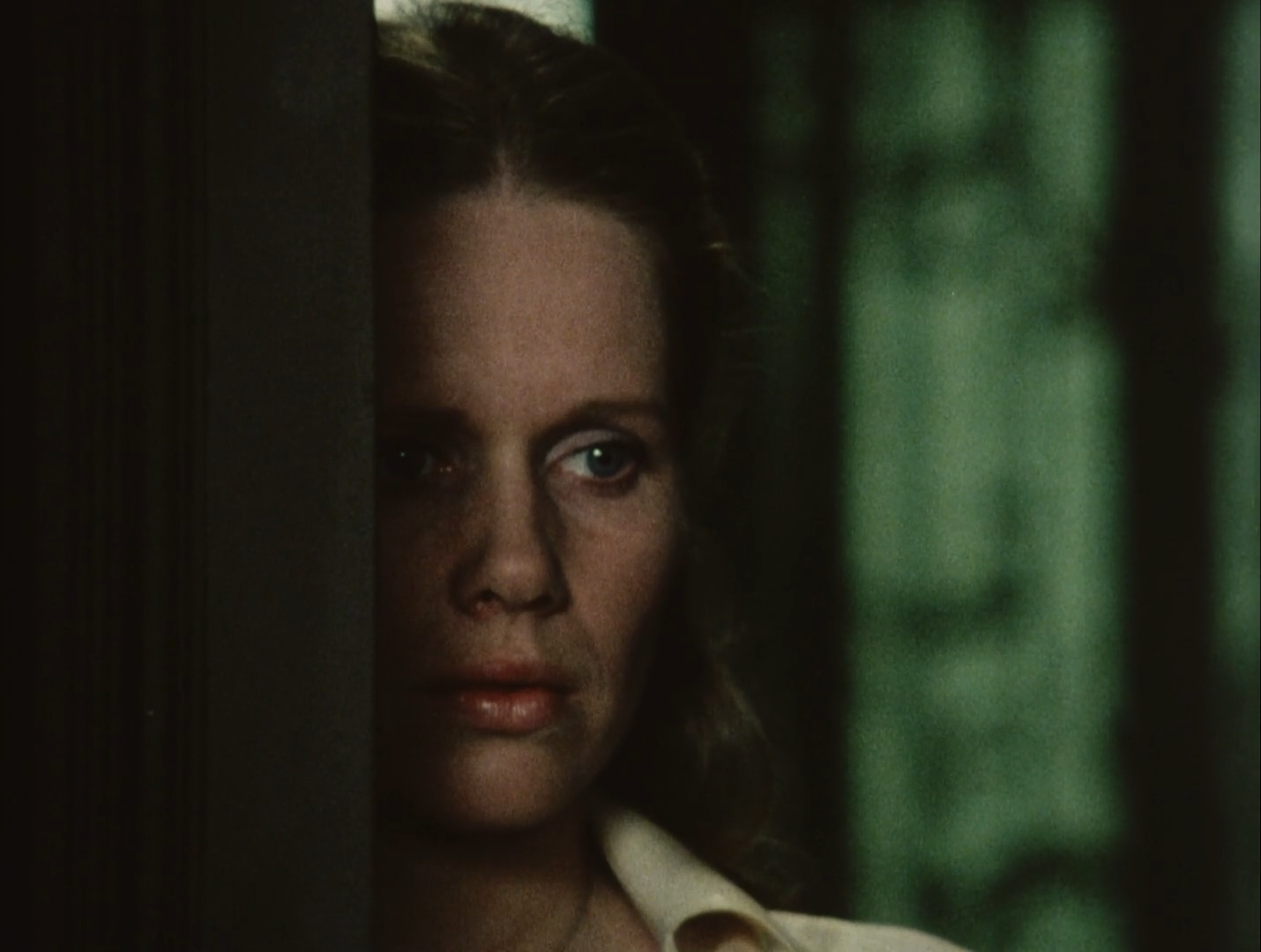

This version of Fellini is often little more than a passive observer accompanying our journey, while the second cinematic representation of the filmmaker manifests as an older, wiser extension of the same man – an unseen tour guide of sorts, offering amusing descriptions and opinions on Rome’s eclectic culture through omniscient voiceover. He is our constant companion through this adventure, possessing a whimsical self-awareness as he introduces a “portrait of Rome” exactly as a young, naïve Fellini once perceived it – “a mixture of strange, contradictory images.” Later as we stumble across Italian actress Anna Magnani walking home to her palazzo, this voiceover even holds a conversation with her, distilling all the facets of Rome down to this living symbol who has lived out its many lives on film.

“Rome seen as vestal virgin, and she-wolf. An aristocrat, and a tramp. A sombre buffoon.”

On occasion, Roma does not always handle these fourth wall breaks so well, leading to some patchiness in one highway scene that turns the camera back on Fellini’s own crew capturing the traffic jam. Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend is the obvious influence here, as we observe anarchy unfold on the roads one stormy night. Dead animals, burning trucks, hippie protestors, and police barricades are illuminated under harsh spotlights to paint an image of societal breakdown, but for once the chaos seems to escape Fellini’s control.

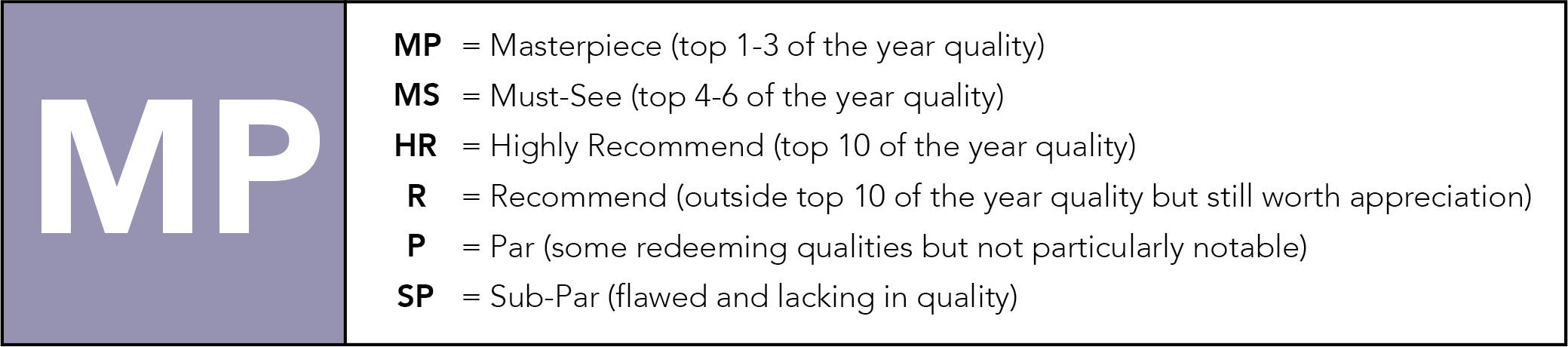

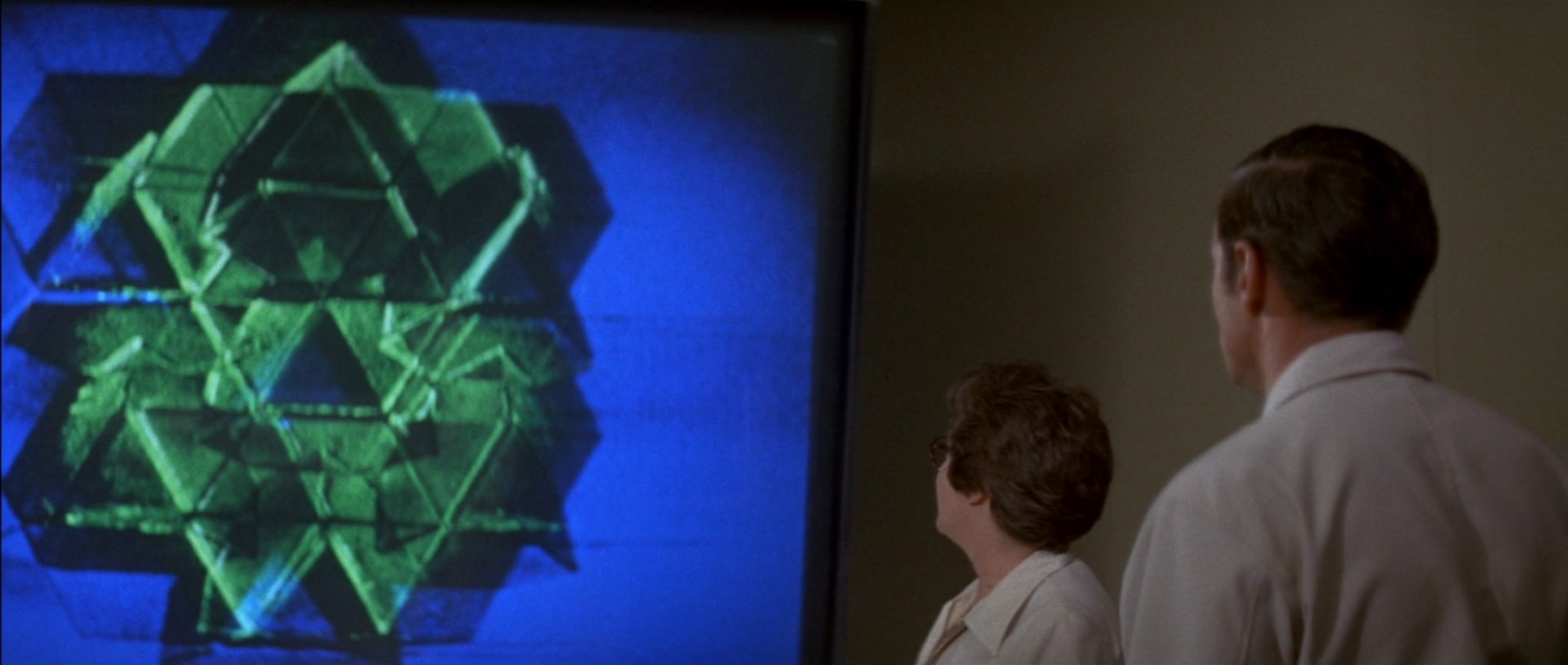

It is evident that Fellini handles the mayhem with greater poise when he is aligning these disordered elements under unified set pieces, digging into the bedrock of culture and history the city quite literally rests upon. The wondrous regard these people hold for their heritage is not to be outdone by their relentless pursuit of progress, as industrials drills paving the way for a new transit system smash the walls of an ancient Roman house to pieces, revealing alabaster sculptures, mosaics, and frescoes that have miraculously survived for two thousand years. “Look how they seem to be staring at us,” one woman remarks as these artworks cast a stern eye upon their new visitors. Suddenly, the paint’s exposure to the outside air triggers a rapid deterioration, and thus these representatives of the ancient world cast their final judgement on modern civilisation for its graceless, irresponsible ineptitude.

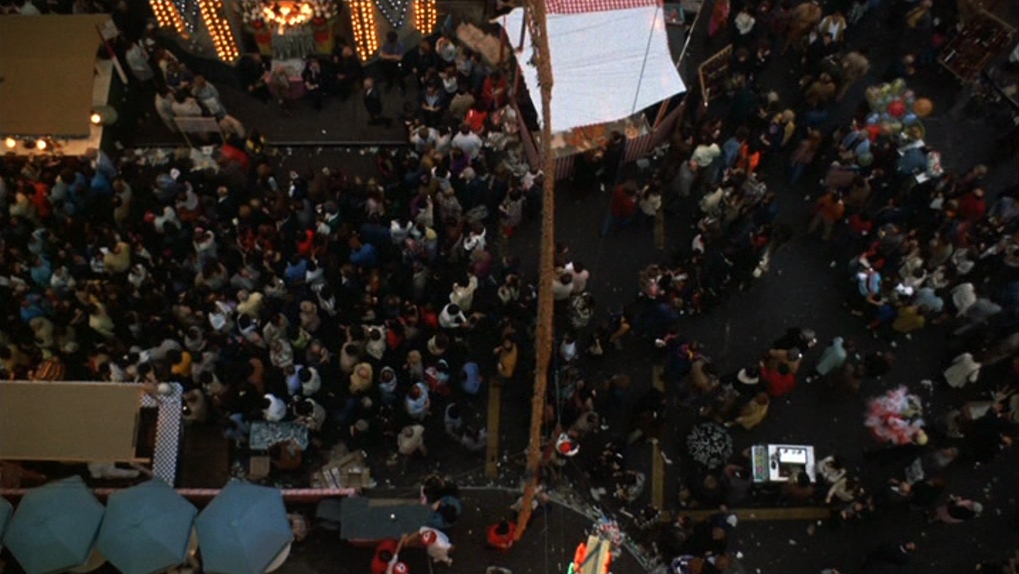

Still, little can erase the immense pride of a culture that annually celebrates the Festa de’ Noantri – literally translating to ‘Festival of Ourselves.’ Fellini stations his handheld camera in a car as it passes by colourful lights, bustling crowds, and folk musicians filling the air with joy, capturing a slice of the real celebration in an almost documentary-like manner, and even bringing in American writer Gore Vidal to reflect on his life in Rome. “This is the city of illusions,” he ponders to an audience of rapt listeners. “It’s a city, after all, of the church, of government, of movies. They’re all makers of illusions.”

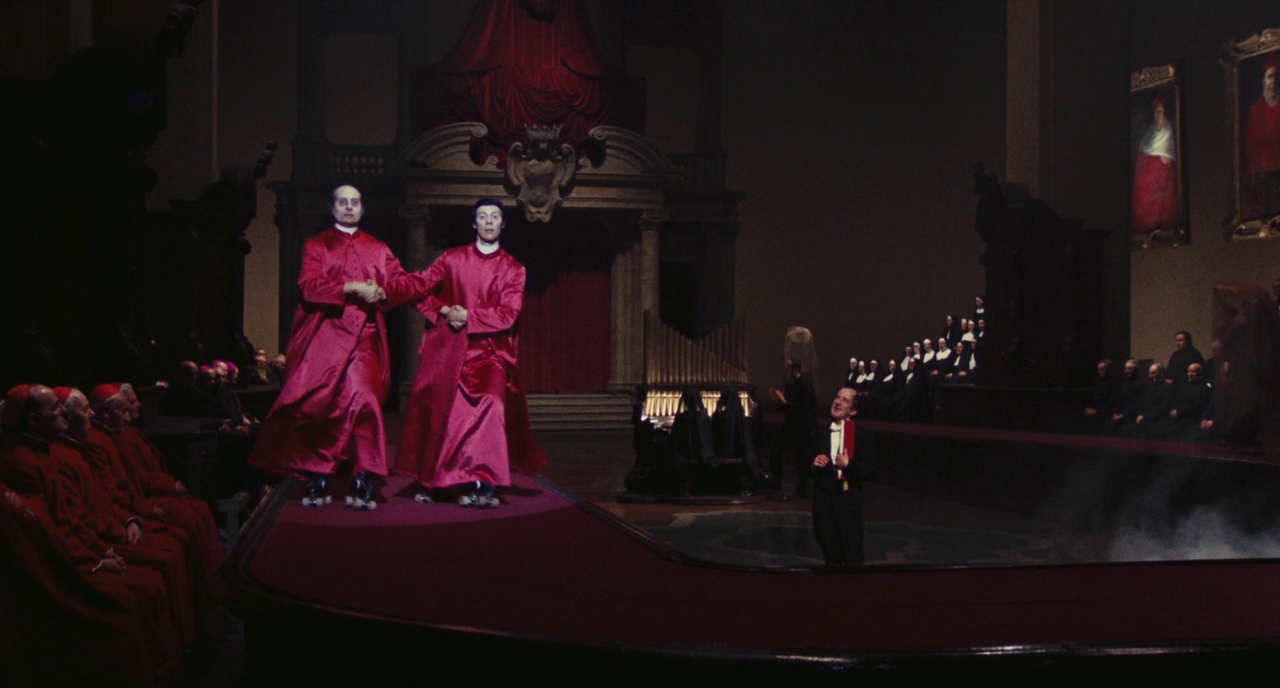

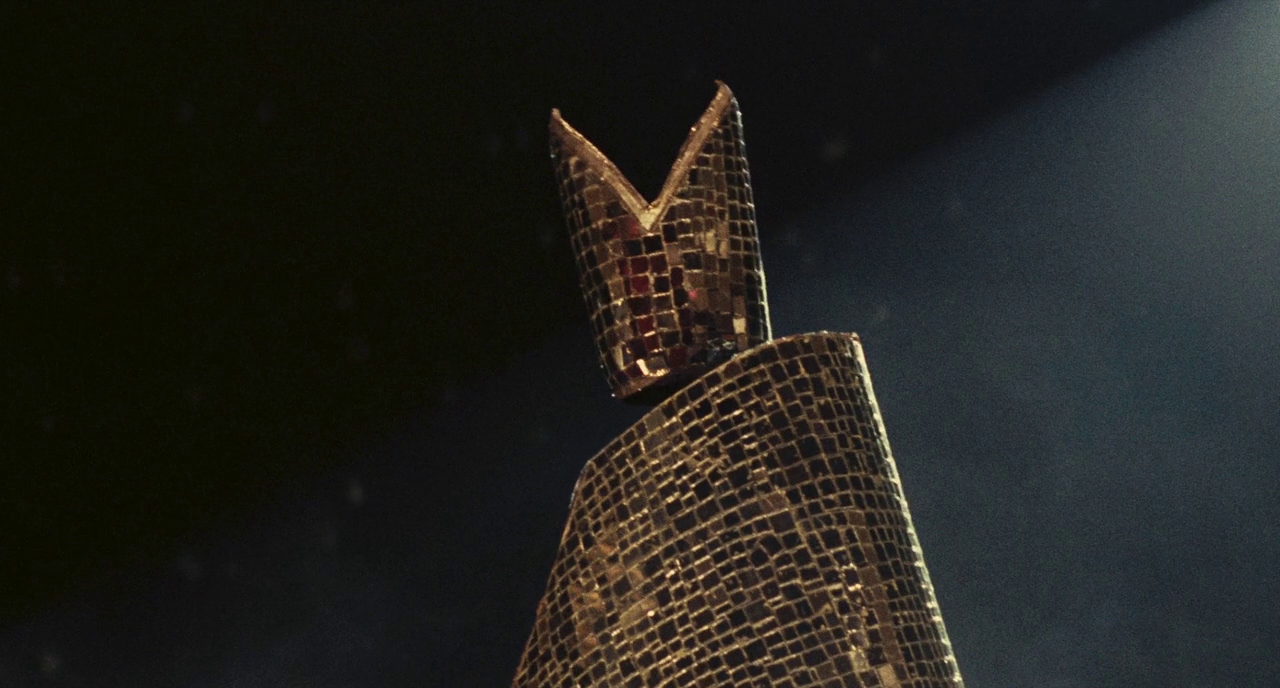

Fellini does not attempt to escape from beneath the shadow of this reputation either, but rather devotes his vision of Rome to its extraordinary artifice, understanding that the truth never lies far from its projected façade. With Roma’s production taking place a few years after Vatican II, this is especially relevant to the church’s struggle of identity in a modern world, and thus he launches a scathing attack upon its attempted reinvention through a hilariously gaudy fashion show.

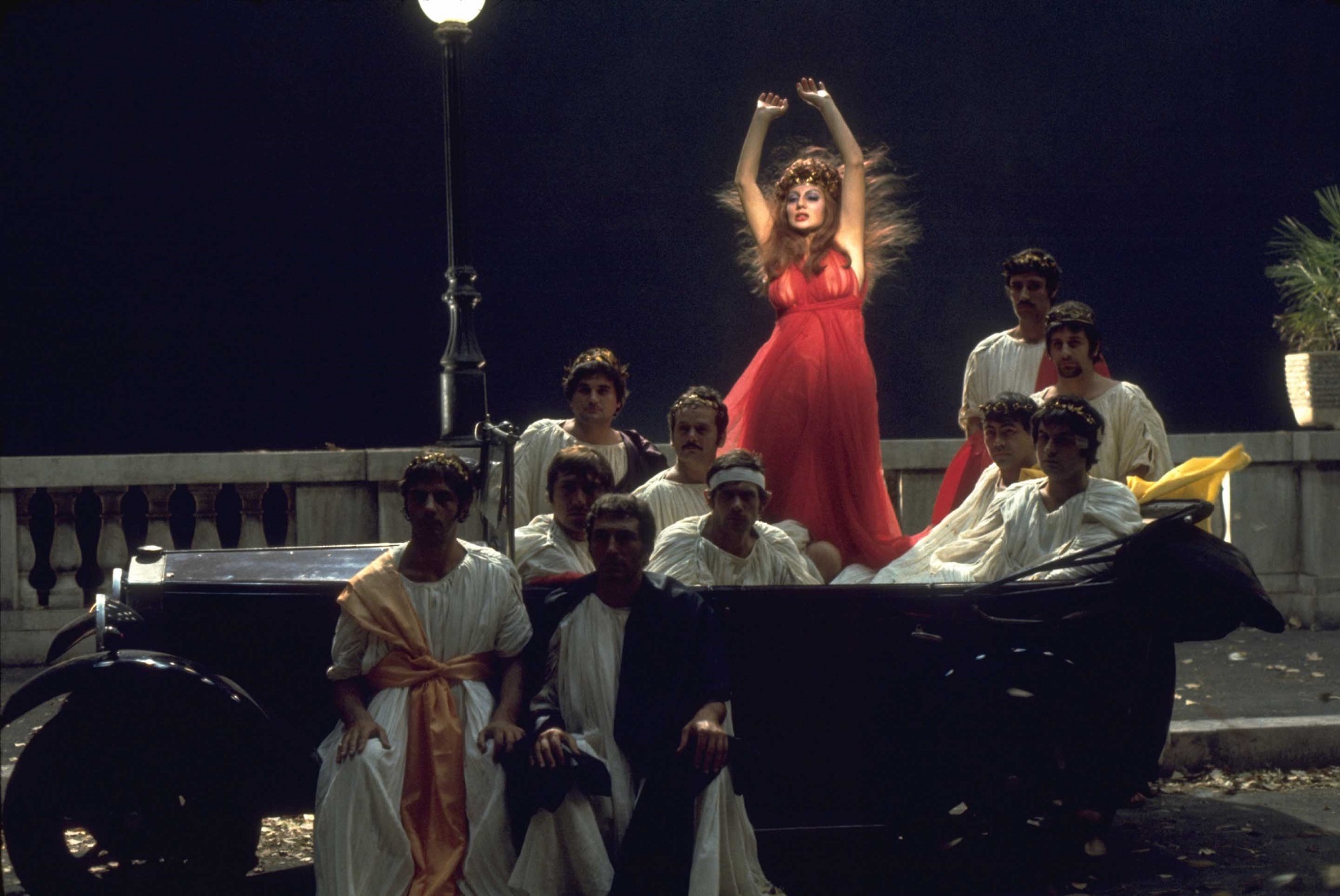

“Model number one: Patience in a classical line of black satin for novices,” the emcee announces to the crowd of cardinals, bishops, and nobles, as a pair of nuns walk down the catwalks in glossy habits and leather boots “suitable for Arctic wear.” Next, two more nuns with headdresses that flap like turtledove wings, priests on roller skates clad in “robes for sport,” and then men in frilly doilies swinging thuribles with choreographed panache – “Elegance and high fashion for the sacristan in first-class ceremonies.” The ecclesiastical accoutrements only grow more ridiculous, eventually culminating in the arrival of the Pope himself on a blinding white set, radiating sunbeams as the audience collapses to their knees in awe.

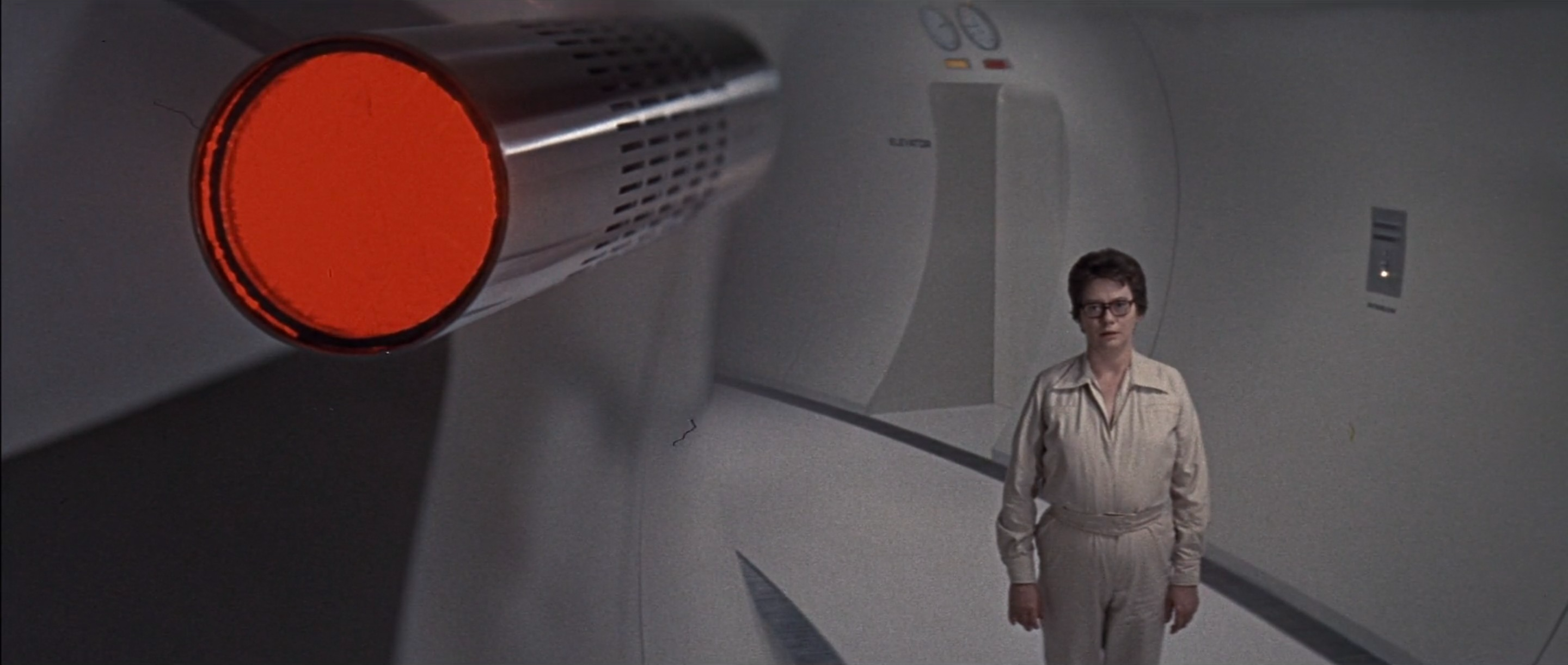

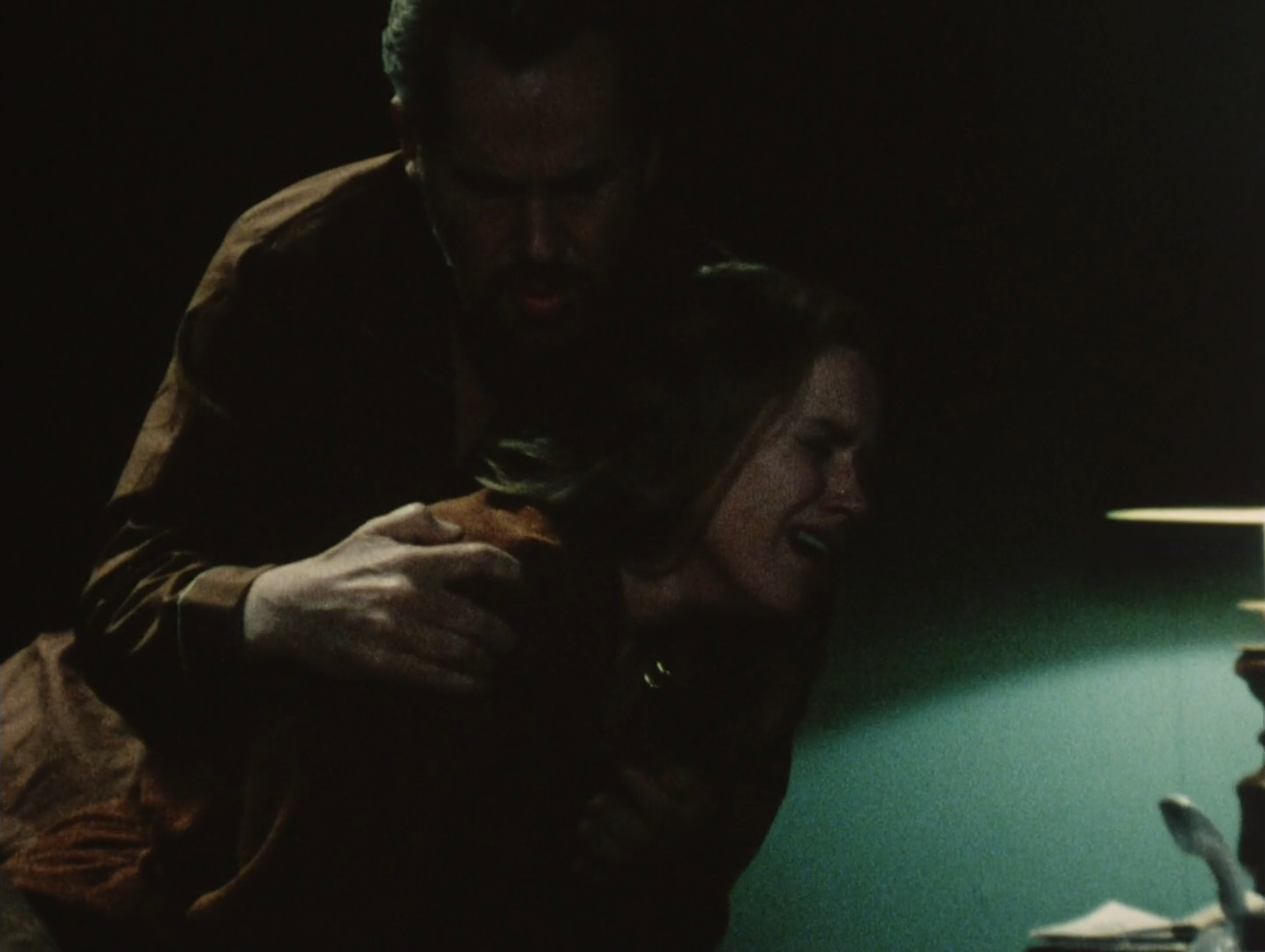

Costume designer Danilo Donati must be commended for the visual extravagance of this vignette, though it is Fellini’s genius which unites each garment under a single, scathing criticism of religious hypocrisy, and its attempts to win modern audiences through material spectacle. Then again, how can we blame the church for appealing to the masses in such an excessive manner when the people themselves are so blinded by escapist self-indulgence? Men from across the lower and upper ends of this society are far more likely to frequent local bordellos for a taste of intimacy, as Fellini only separates their endeavours by the sophistication of the facilities themselves. In the shabbier brothel, a long corridor fills with working class men hoping to pair off with a woman, before it is eventually shut down by police. In the more luxurious one, older men take their pick of the escorts before taking an elevator up into grand bedrooms decorated with red wallpaper and classical paintings.

Art and entertainment similarly prove to be effective distractions from the ills of the modern world, manifesting in the 1970s as a film director neglecting to depict the negative aspects of Rome, and in the 1940s as a vaudeville show that unites audience members in laughter, bawdiness, and nationalistic sentiment. The musical and comedy acts run for a little too long here, but the announcement of Germany and Italy’s successful defence of Sicily that interrupts the performances is worth it, erupting in disconcerting cries of support from the crowd.

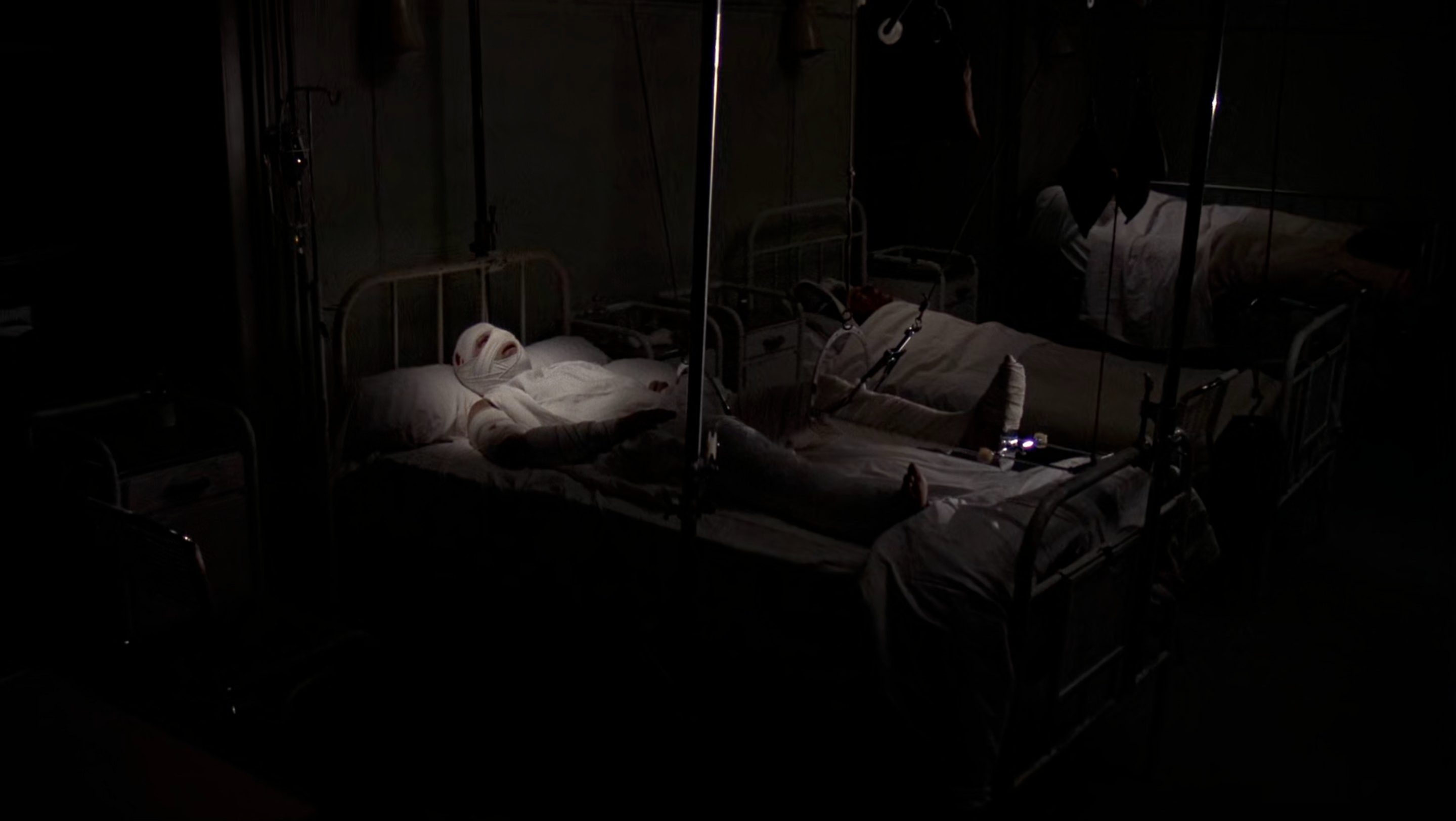

The irony that this jubilant resolve dissipates into pandemonium the moment sirens start blaring a few short moments later is not to be missed. “Whose baby is this?” one patron shouts upon discovering a baby left alone in the evacuated theatre, while outside Fellini shoots the emptying streets in a chilly blue wash. Though present-day Rome has long moved past the terror and instability of World War II, the insecurity that comes to light here is a ghost that continues to haunt this city – a city which, as Vidal elucidates, “has died so many times and was resurrected so many times.”

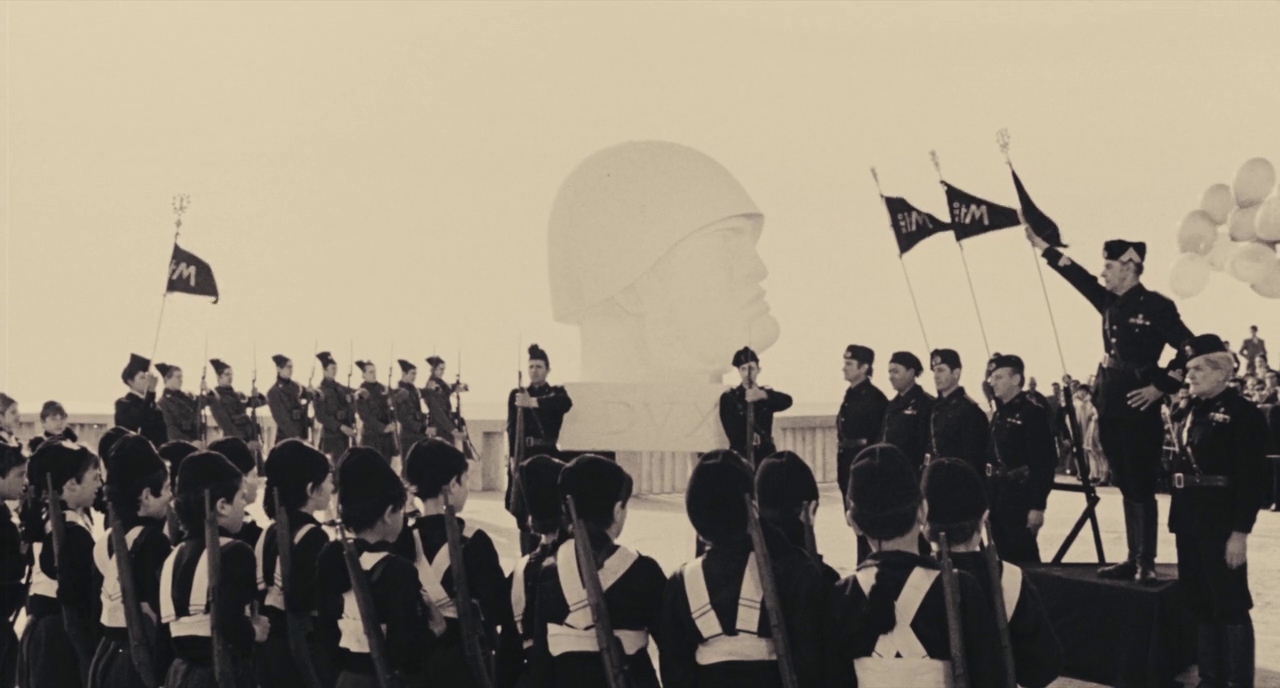

More specifically, it is Rome’s historical inclination towards fascism which can’t quite be expelled from its culture, and which becomes the subject of the town fool’s rhyming couplets comparing Italian dictators across time. “This fascist shit, his head is split,” he cackles at a damaged statue of Julius Caesar, before turning his insubordinate poem to the 1940s.

“Now we’ve got another meanie,

By the name of Mussolini.”

Fellini’s obvious disdain towards the police in the 1970s timeline formally brings this partisan statement full circle, noting that despite the political lull, there remains an oppressive, authoritarian influence quashing freedoms in contemporary Rome. These people may find any excuse for a communal celebration of family, art, food, or religion, and yet such lively passions can sway dangerously towards prejudice with the right provocation. “It seems to me the perfect place to watch if we end or not,” Vidal predicts, and by the end of Roma, Fellini has thoroughly substantiated his claim. Within this vividly surreal portrait, its culture is a vibrant epicentre of history and modernity, community and intolerance, highbrow art and lowbrow entertainment – and worth cherishing in all its wonders, contradictions, and flaws.

Fellini’s Roma is currently available to buy from Amazon.