Bernardo Bertolucci | 2hr 9min

This review discusses themes of sexual violence, emotional abuse, and the ethical controversies surrounding the production of Last Tango in Paris. It includes references to the mistreatment of actress Maria Schneider and the lasting psychological impact of the filming process. Reader discretion is advised.

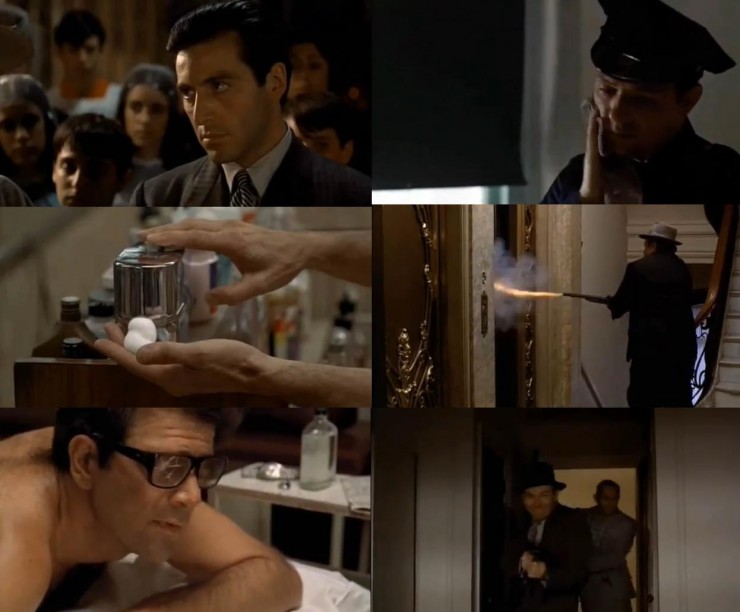

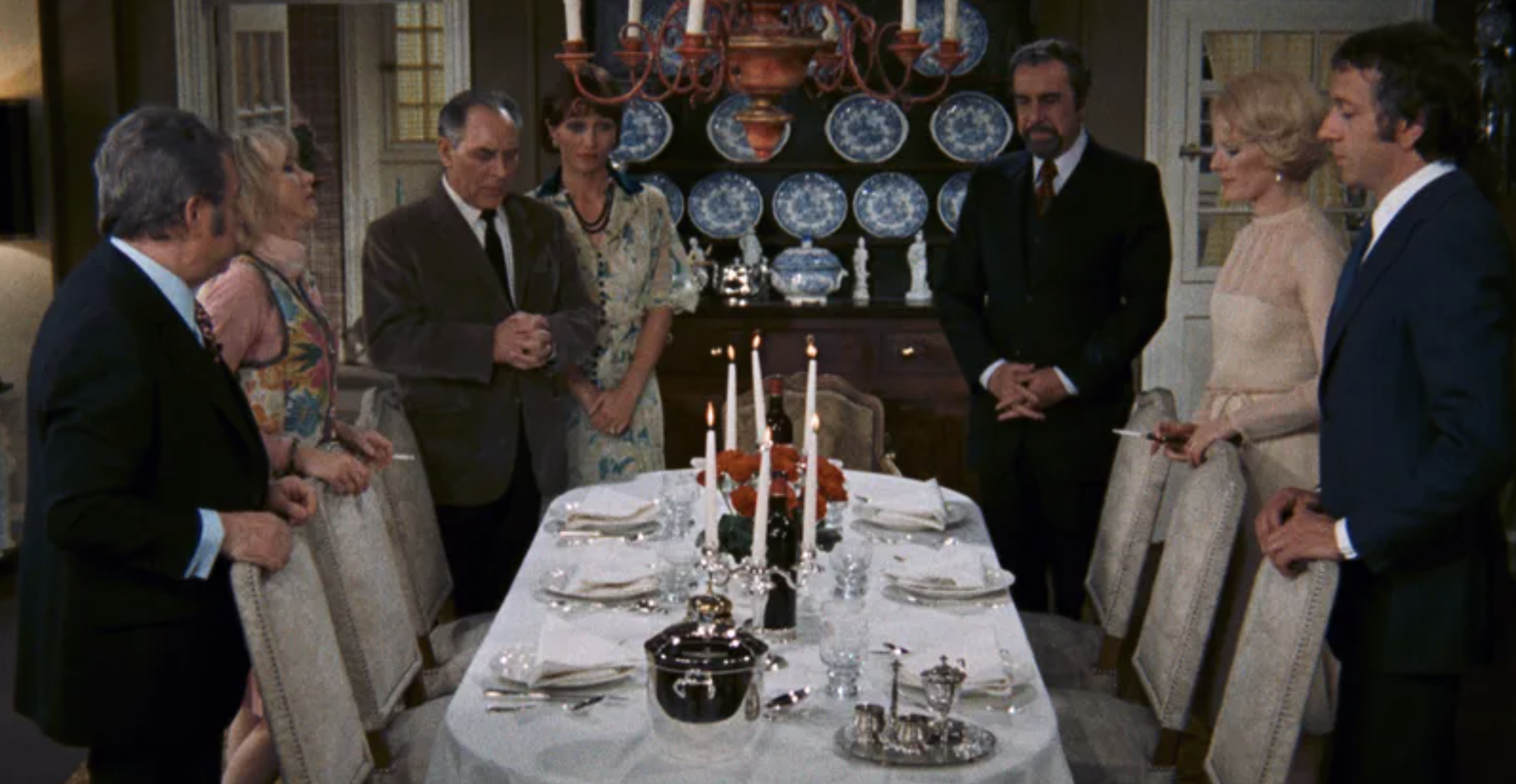

After encountering each other in an empty Parisian apartment through pure happenstance, it doesn’t take long for grieving widower Paul and young actress Jeanne to begin their impromptu, passionate affair. The residence is currently for lease, and although both are interested in renting it for themselves, there is no bitter competition in their initial exchange – merely small talk about the fireplace, potential furnishings, and the old-fashioned architecture. Before either knows what is happening though, he is picking her up in his arms, and they are making animalistic love against the window. As their relationship progresses throughout Last Tango in Paris, their sex takes on more sensual dimensions, though this is far from the last time we will see it devolve into an act of crude, carnal instinct.

This entire affair hinges on a single rule, Paul declares: to maintain an ongoing emotional detachment, neither are to divulge a single personal detail about themselves to the other, including their own names. When they are together, their identities are stripped away, as are the expectations and norms of society. For Jeanne, this means a break from her frustrating engagement to Thomas, an aspiring filmmaker who often treats her more as an object of his art than a romantic partner. For Paul on the other hand, it runs much deeper. This is a man whose is deeply aggrieved by the suicide of his wife Rosa, and now seeks an outlet for emotions that he cannot fully understand or control. Within this apartment, there is no need to mull over the despair that has clouded his mind with self-loathing. Here he is in total control of his connection to another human, and free to indulge his most disturbing impulses.

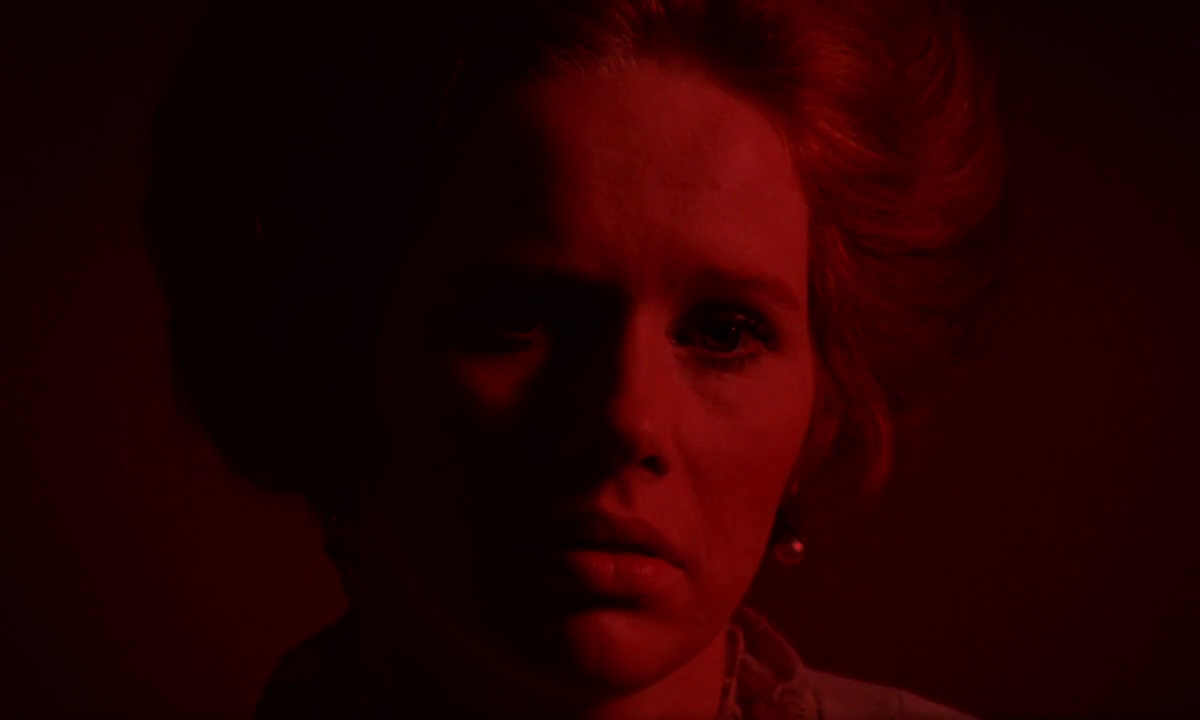

Of course, it is plain to see how this anonymous affair is far more an escapist fantasy than it is a path to healing, and Bernardo Bertolucci’s character study is unafraid to plunge the thorny depths of such a paradoxical arrangement. What Paul and Jeanne effectively establish here is a form of intimate disassociation, embracing each other’s bodies while neglecting everything else. As he grows more possessive, his dirty talk veers perversely into bestiality and necrophilia, though this debauchery seems to stem more from unresolved anger than lustful desire. The moment he truly crosses the line also happens to be the point that Bertolucci did the same during production, and there is no brushing past the abject inhumanity of what both he and Marlon Brando submitted actress Marie Schneider to here.

Art may be the purest distillation of its creator’s soul, yet as is the case in Last Tango in Paris, it can also be so horrifyingly effective that we are compelled to look away from the malevolence revealed. As a portrait of emotional and sexual abuse, Bertolucci’s film is incredibly powerful, but it is no coincidence either that it comes from someone who is responsible for the same trauma he is depicting. Reasoning that an authentic performance was worth letting his actress suffer, he did not inform Schneider that Brando would be lubricating her with butter before filming a rape scene. Consequently, he only succeeded in revealing his disregard for Schneider’s ability as an actress, and implicating himself as the hypocritical target of his own criticism.

That Schneider would continue to live with the psychological consequences of this assault for the rest of her life while Bertolucci and Brando showed little remorse only complicates the legacy of this scene further. As such, a damning parallel emerges between Bertolucci and the character of Paul, seeing both use artificial constructs of identity as self-expression while holding no regard for the emotional toll being imposed on others. For better or worse, art lays bare humanity’s extremes, and Last Tango in Paris is no exception in leaving us to grapple with its flaws and contradictions.

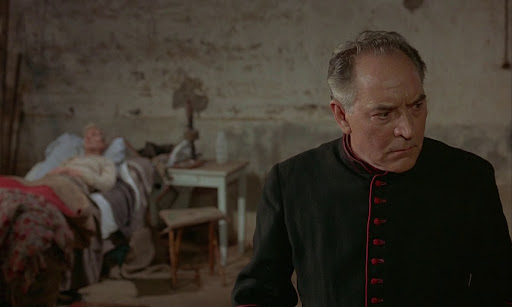

There is certainly no denying the excruciating vividness of such an introspective study either, prodding at open wounds in Paul’s psyche that refuse to heal and provoke guttural manifestations of inner torment. While Brando sordidly adopts an almost bestial physicality in these moments of primal release, he also displays an eloquent vulnerability through his monologues, delivering one of his finest scenes at the viewing of Rosa’s body. It is impossible for him to separate the love, grief, and vitriolic anger that he harbours, and so here they all chaotically burst out at once, pouring slurs, tears, and apologies over her open casket.

“Our marriage was nothing more than a foxhole for you. And all it took for you to get out was a 35-cent razor and a tub full of water. You cheap goddamn fucking godforsaken whore, I hope you rot in hell. You’re worse than the dirtiest street pig anybody could ever find anywhere.”

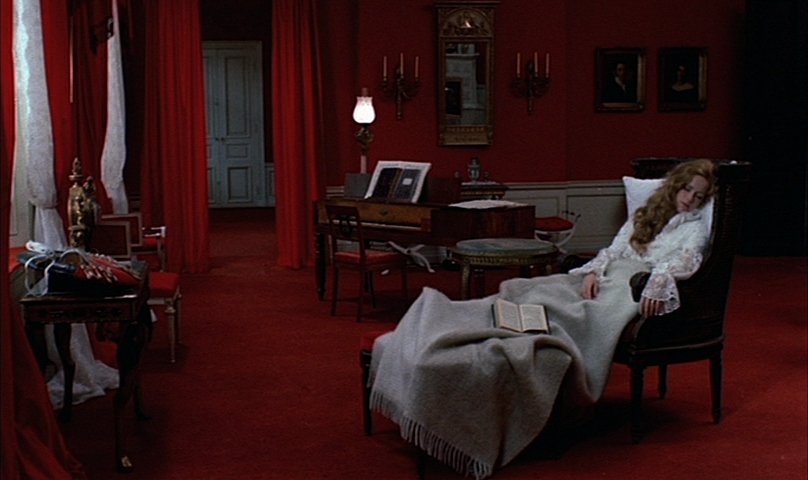

As such, it makes sense that Jeanne represents a blank beacon of innocence who he can map Rosa’s identity onto, as well as a target of his overbearing love and abuse who doesn’t ask for explanations. Reduced to this state of vulnerability, she claims to feel like a child again in his arms, and the two exhibit a light playfulness when they make up gibberish names for themselves. Even the apartment that hosts their affair and which Paul never quite finishes moving into embodies this nondescript purity, forcing them to lounge around on the floor in the absence of furniture.

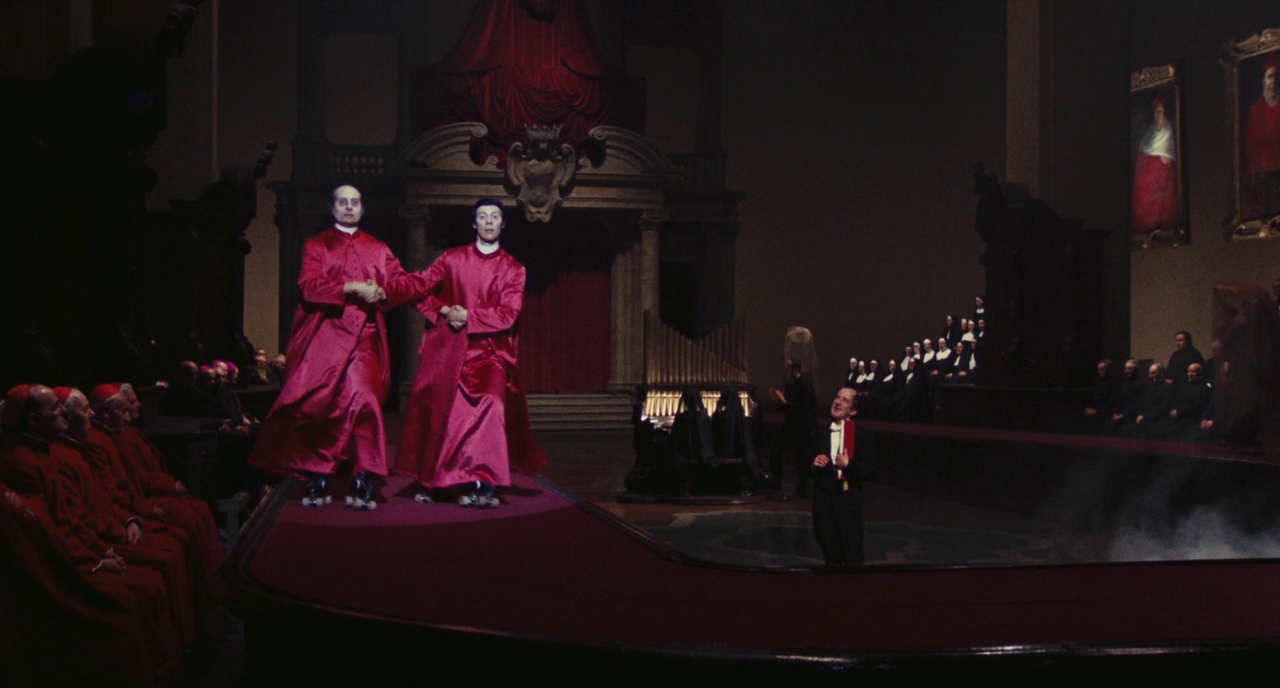

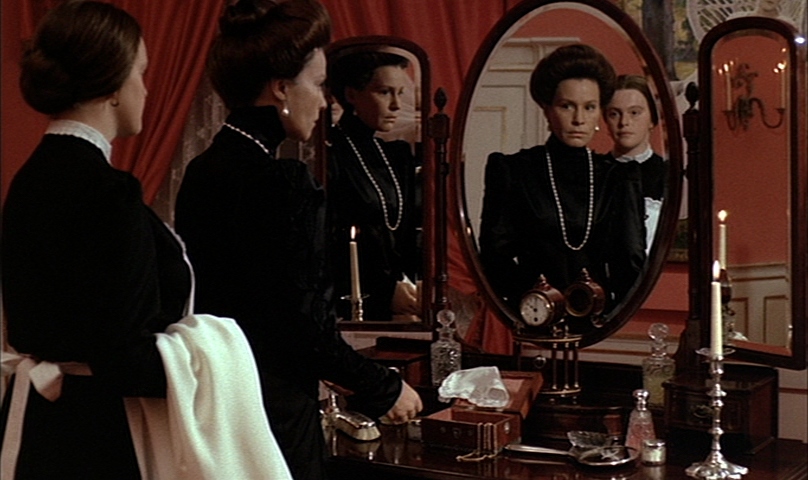

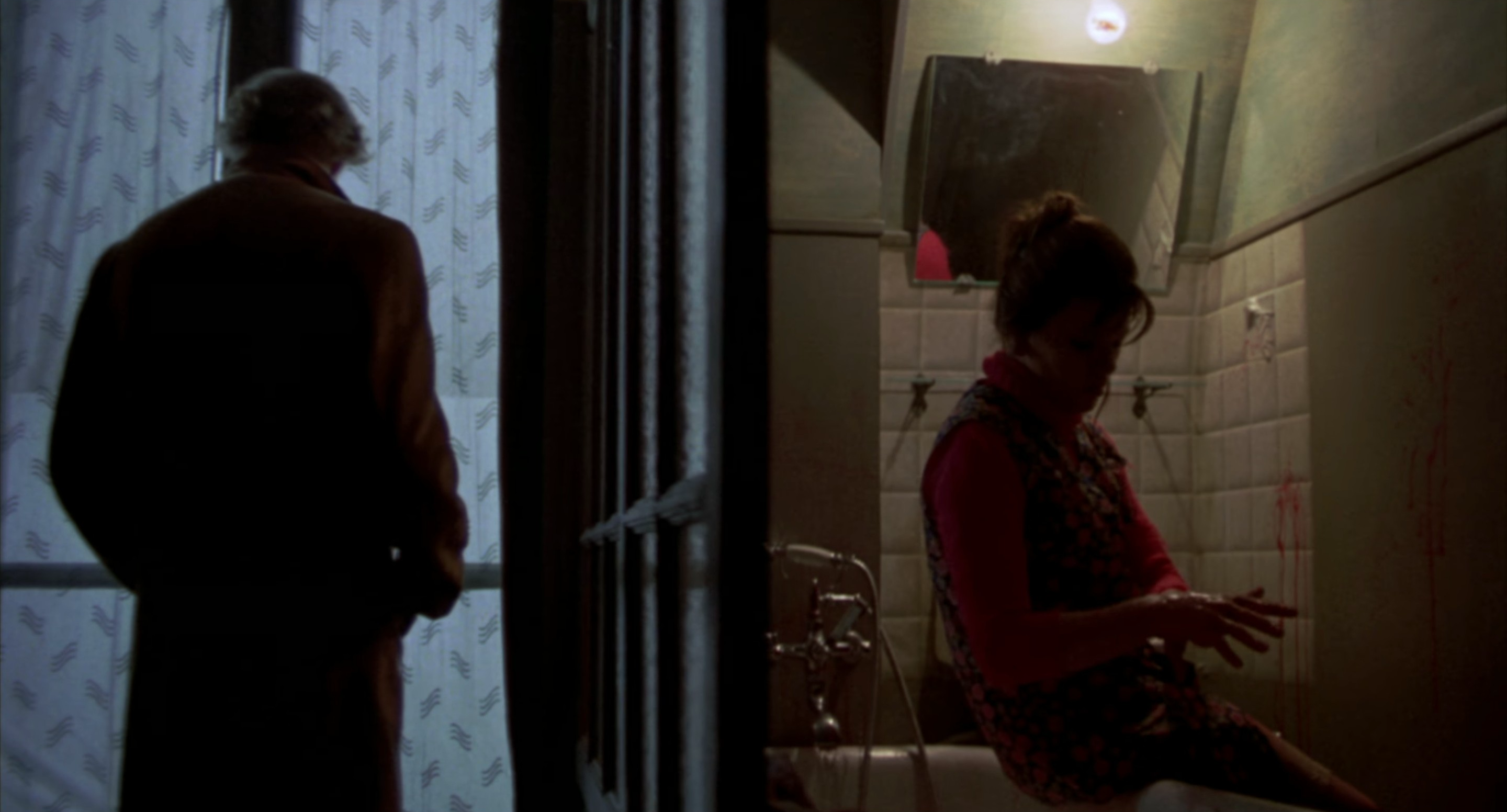

Nevertheless, Bertolucci works stylistic wonders with such a sparsely decorated setting, drawing on cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s talents to insulate these lovers within their own private world. When they aren’t wrapped up in a tangle of limbs, doorways and windows often become visual dividers, physically separating them within the shared space. The full-length mirror that lazily leans against the wall also makes for some superb compositions, splitting them between isolated frames, while the frosted glass of the reception area underscores their mutual anonymity by blurring their faces into impressionistic watercolours.

There is no doubt a romantic warmth to Storaro’s lighting of the apartment as well, filtering in through the white, translucent drapes hanging from the windows, yet it never quite escapes the melancholy of its soft brown hues and shadows. As much as Paul seeks to separate the outlet for his emotions from the source, the two are deeply intertwined, and eventually drive Jeanne away altogether as she begins to grasp the true depravity of their arrangement.

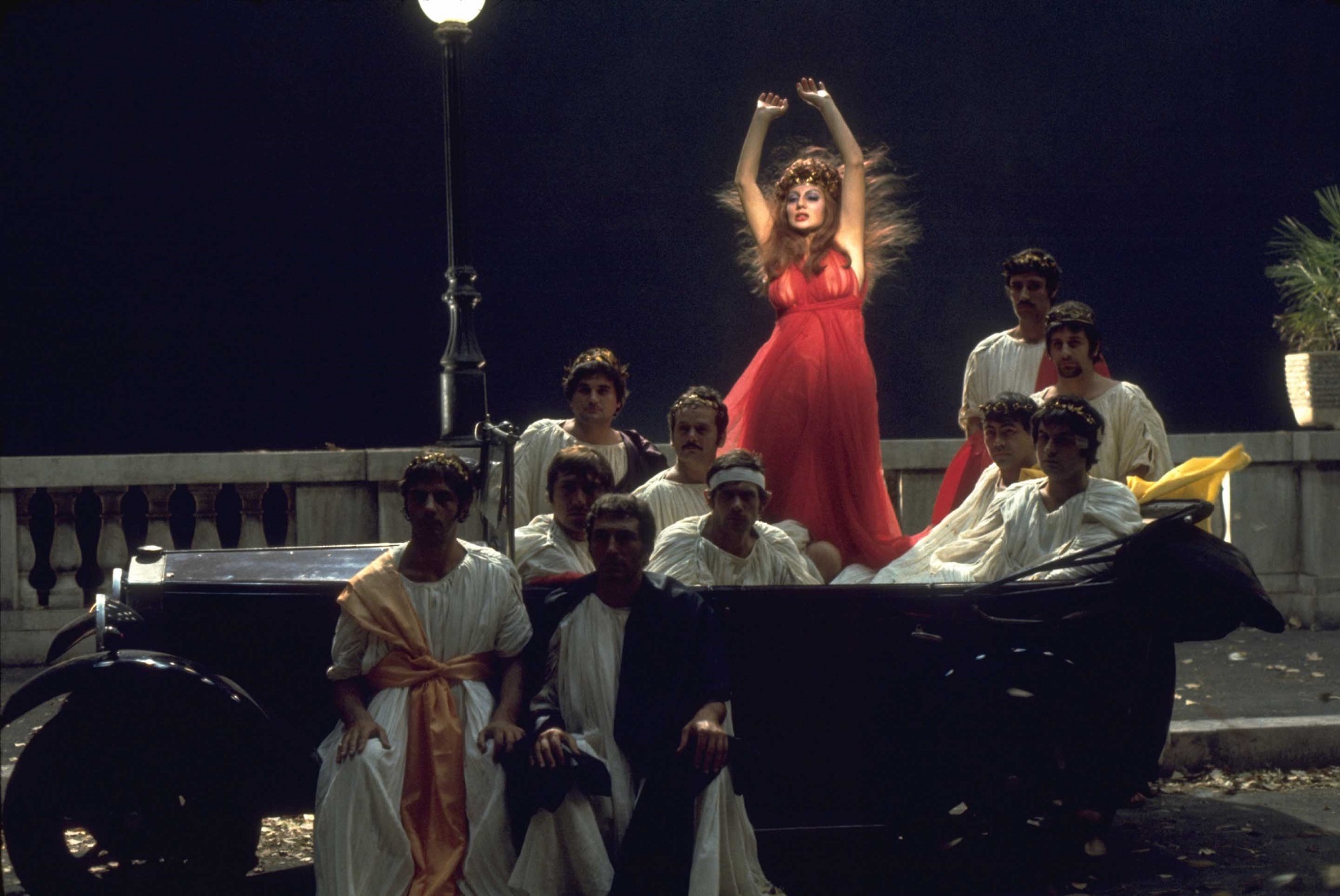

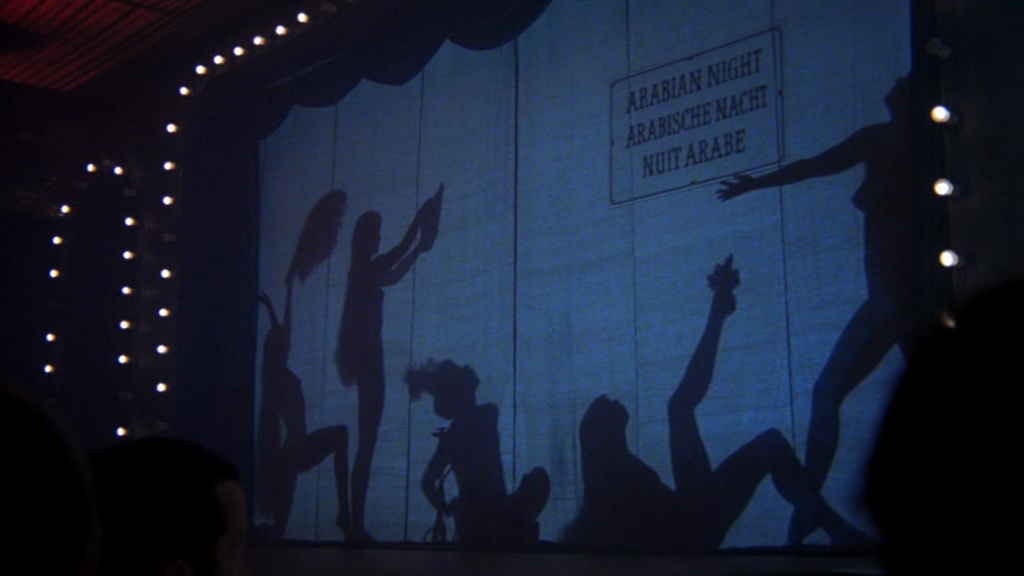

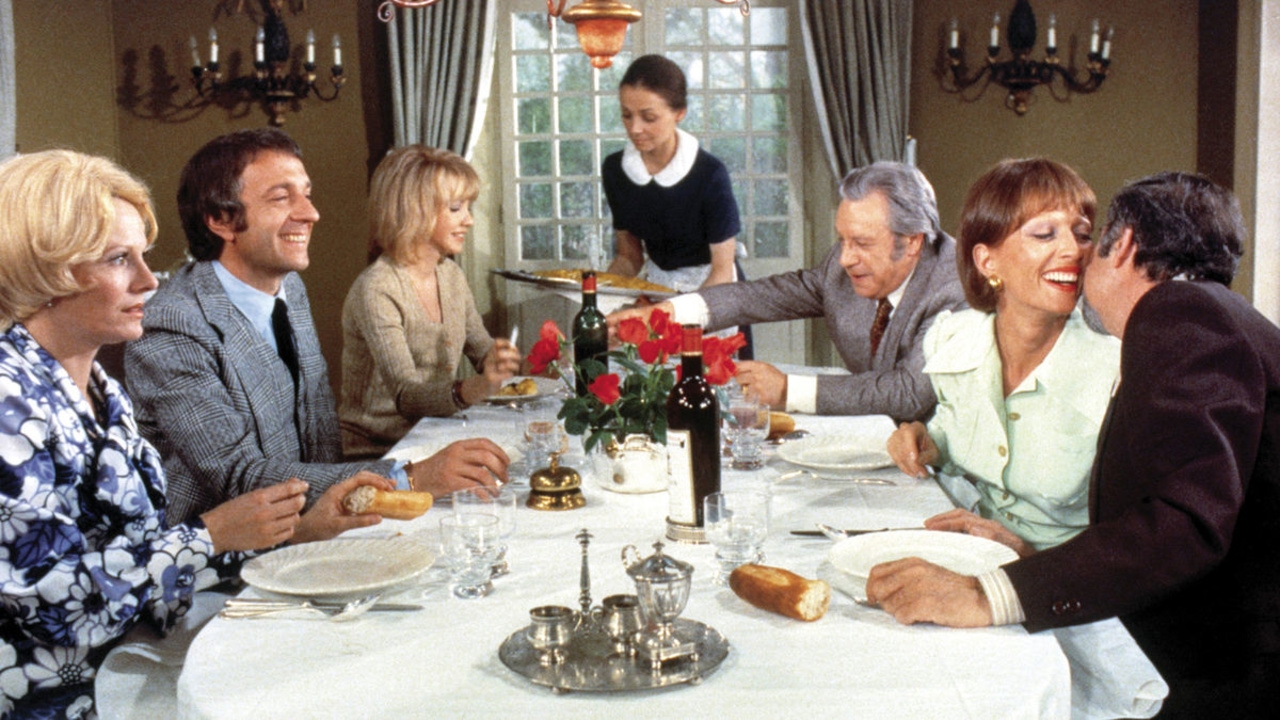

Not that this deters Paul from trying to win her back, and even give up the mask of anonymity which he once so passionately preserved. Quite fittingly, he does not seek to lure her back to his apartment where privacy is guaranteed, but instead sets a public tango bar as the location for their attempted reconciliation. There, Bertolucci’s camera floats across the dance floor where a competition is underway, illuminated by spherical lights hanging from the ceiling and forming a starry backdrop to Paul’s confession of love – not that Jeanne is necessarily ready to start a relationship with this man who she is only really getting to know now.

The push and pull of conflicting emotions in this exchange is symbolically mirrored in the tango it is intercut with, seeing feet sweep in long arches and stamp on short, staccato beats. Perhaps an even more authentic reflection of Paul and Jeanne’s relationship though arrives when they decide to spontaneously join in, horrifying their fellow patrons with an obscene, rhythmless dance of twisting, flopping, and strutting around. In essence, this act is simply another unfiltered eruption of emotions not unlike their lovemaking, though one which they can finally perform in the open without shame.

Still, just because two people have bared their souls to each other does not mean that they are compatible. Where the much-younger Jeanne is ready to leave this part of her life in the past and marry Thomas, Paul clings desperately to what he believes is a sustainable love, even chasing her down the street and back to her apartment. “I want to know your name,” he begs as he strokes her hair, though Jeanne’s response is double-edged, coinciding her verbal answer with a gunshot to his chest.

Maybe Paul genuinely thought he had a chance of starting a new life with Jeanne, though going by the resigned expression on his face as he stumbles out onto the balcony, it seems more likely that he always expected an early grave next to his wife. We do not witness the exact moment that life leaves him, but instead Bertolucci slowly tracks backwards from the city view to reveal his crumpled body, and further into the apartment where a dazed Jeanne begins rehearsing her lines for the police.

“I don’t know who he is. He followed me in the street. He tried to rape me. He’s a lunatic. I don’t know what he’s called. I don’t know his name.”

No one alive knows Paul like Jeanne does, and yet at the same time she isn’t entirely lying. Paul was unknowable, not only to her, but even to himself. To cast damning judgements on others is easy, but as Bertolucci so eloquently illustrates in the warped power dynamic of Last Tango in Paris, examining one’s own psychological torment is a far more dangerously frightening undertaking.

Last Tango in Paris is currently available to rent or buy on YouTube.