Pier Paolo Pasolini | 1hr 38min

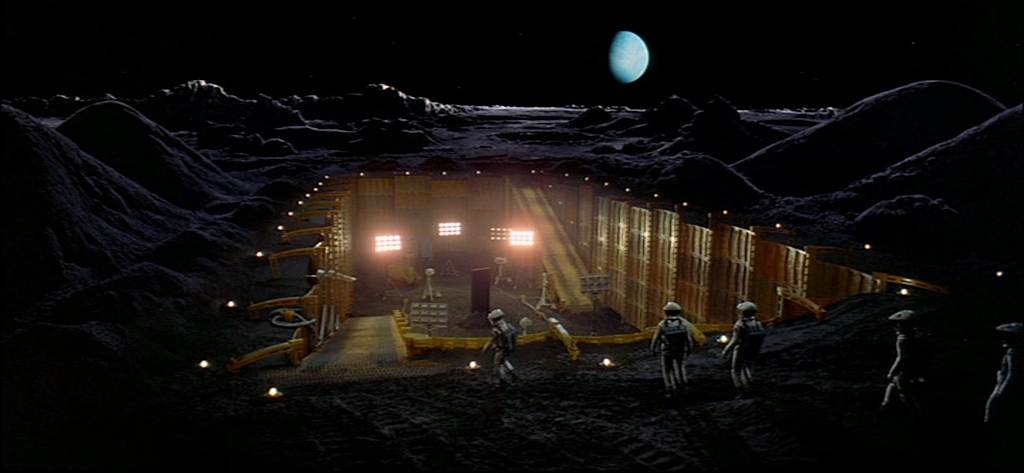

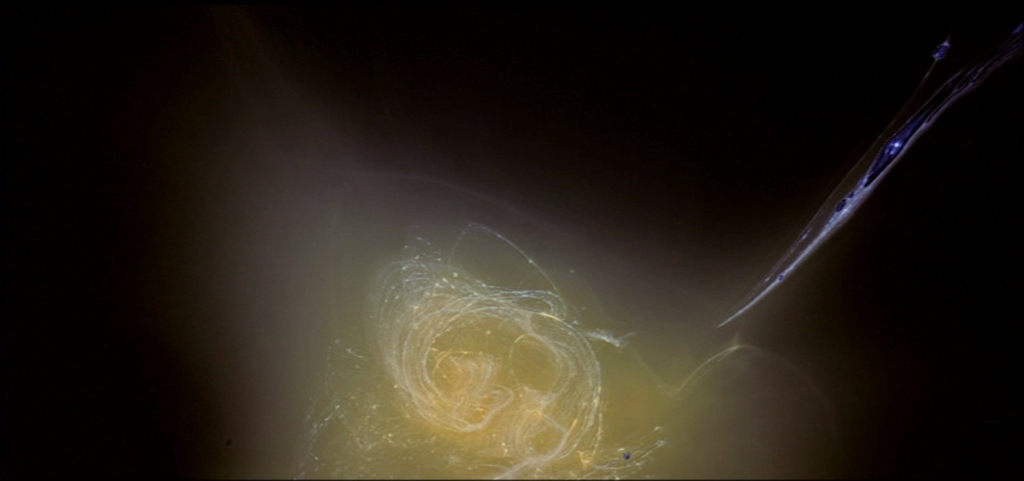

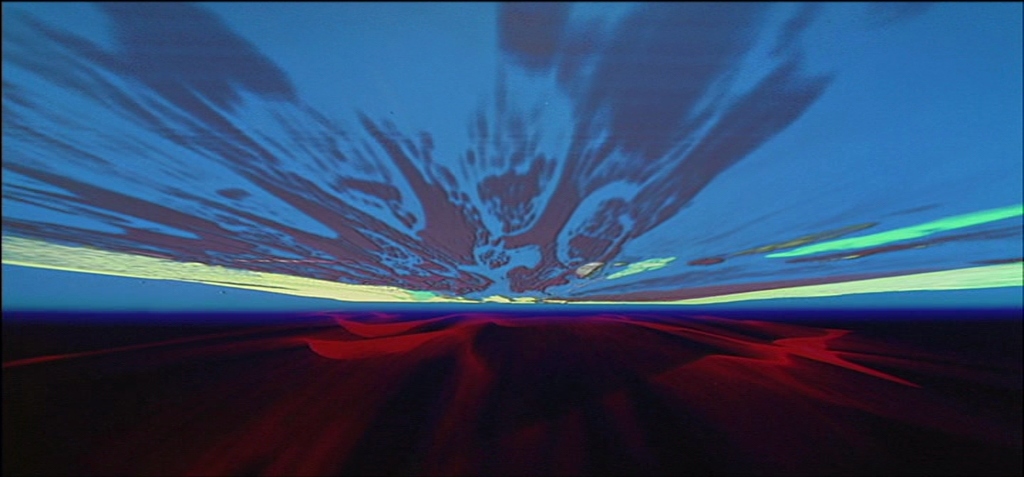

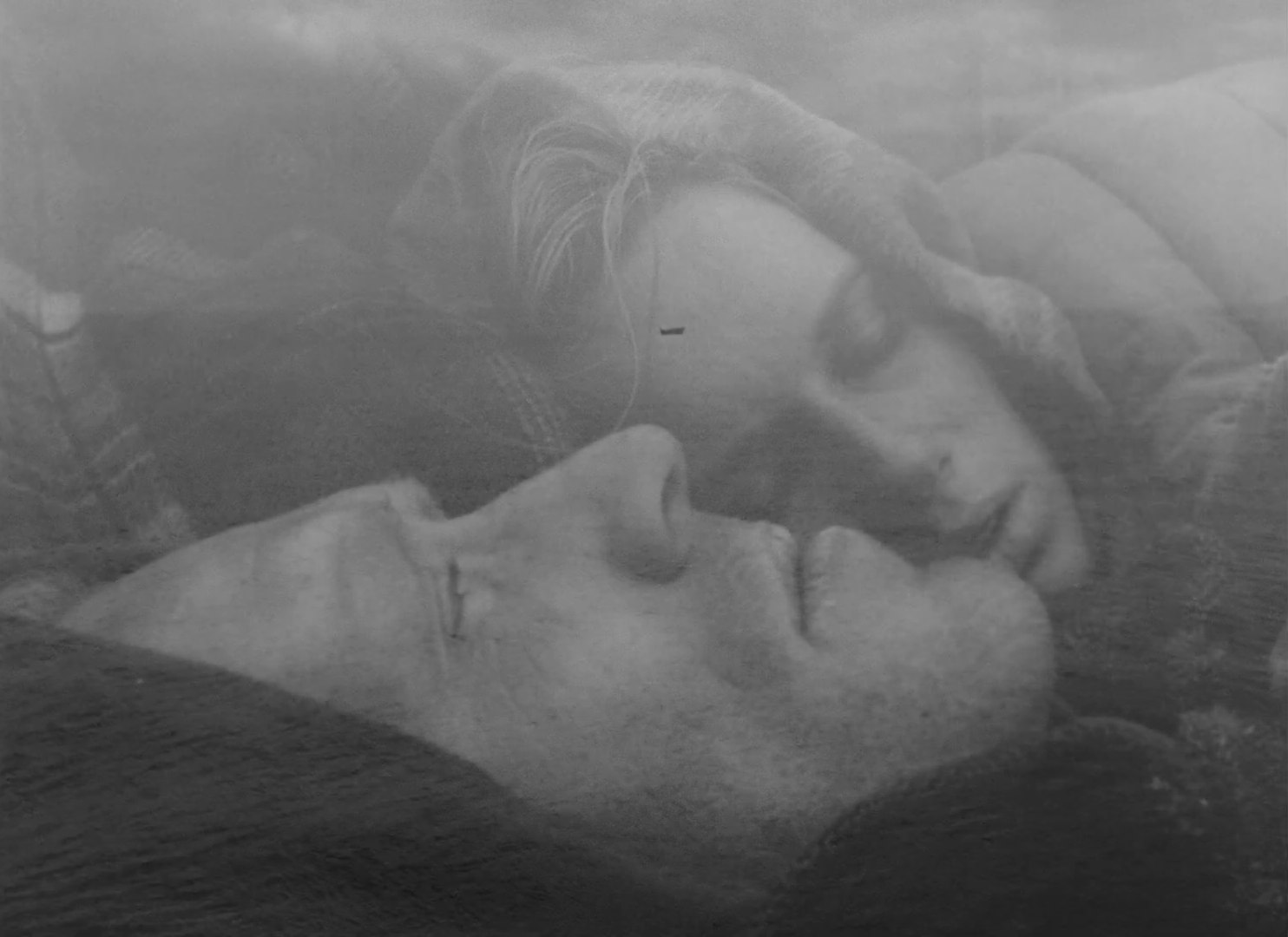

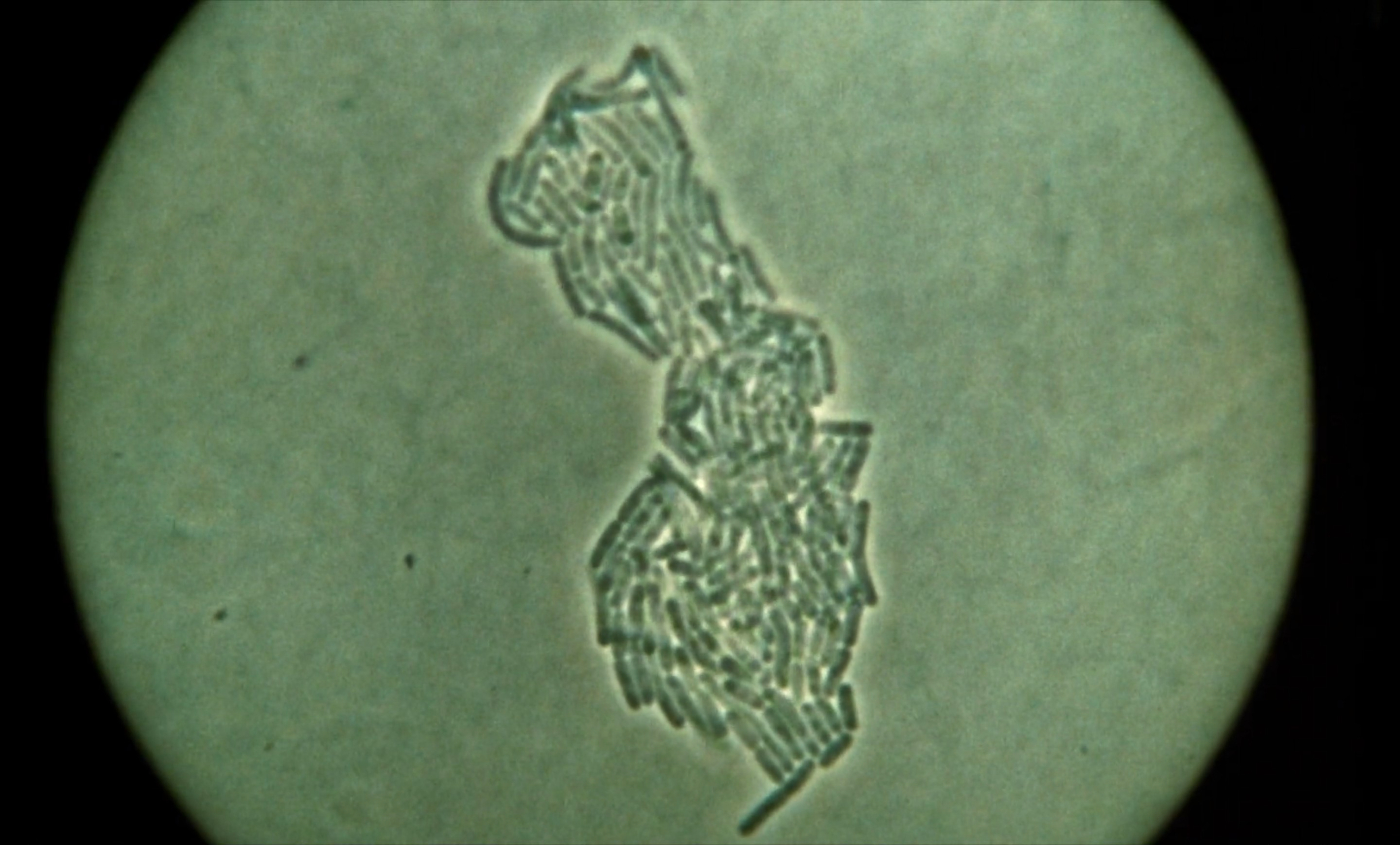

Though Pier Paolo Pasolini imbues Teorema’s structure with the same rigidity as the bourgeoisie’s arbitrary social conventions, his fleeting cutaways to Mt Etna’s chaotic, elemental landscapes are never far away. The volcano is a natural catalyst of transformation and destruction, with its fissures blowing sulphurous steam across slopes of black dust and threatening to erase any semblance of social order within its reach. It wreaks turmoil and madness, both predating and outlasting the entire span of time that humans have lived on Earth. When a mortal being truly grasps a force as primordially unfathomable as this, the effects are wildly unpredictable, though the entropic family portrait that Pasolini paints here captures the complexity of such a world-shifting spiritual experience with mystifying acuity.

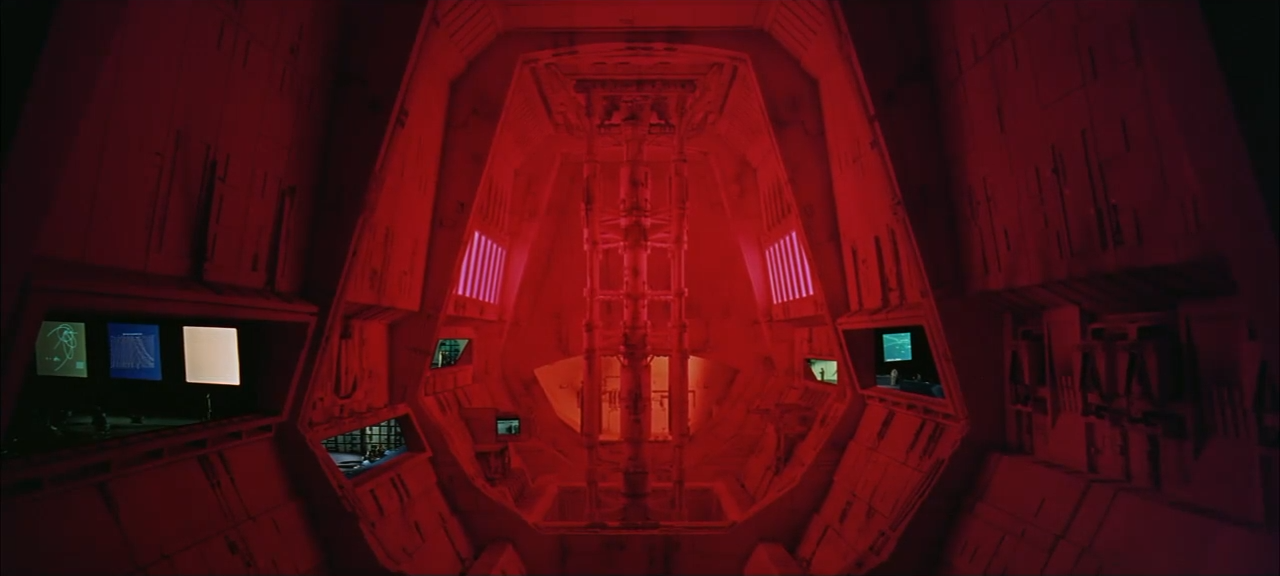

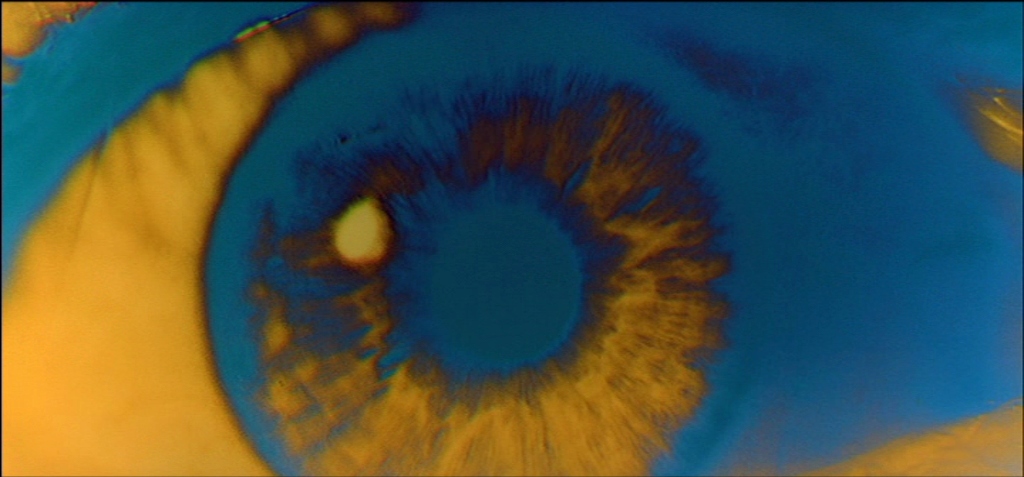

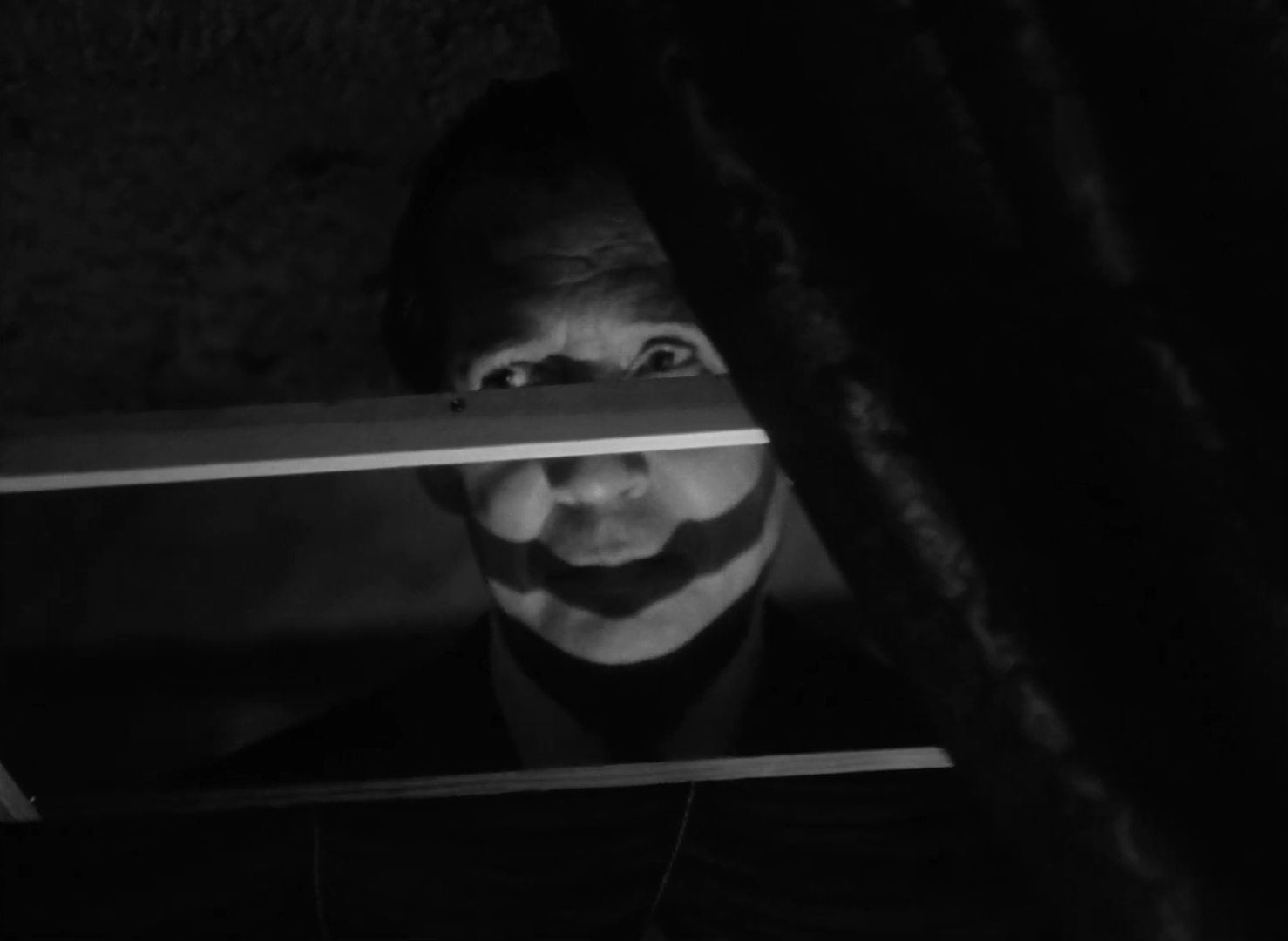

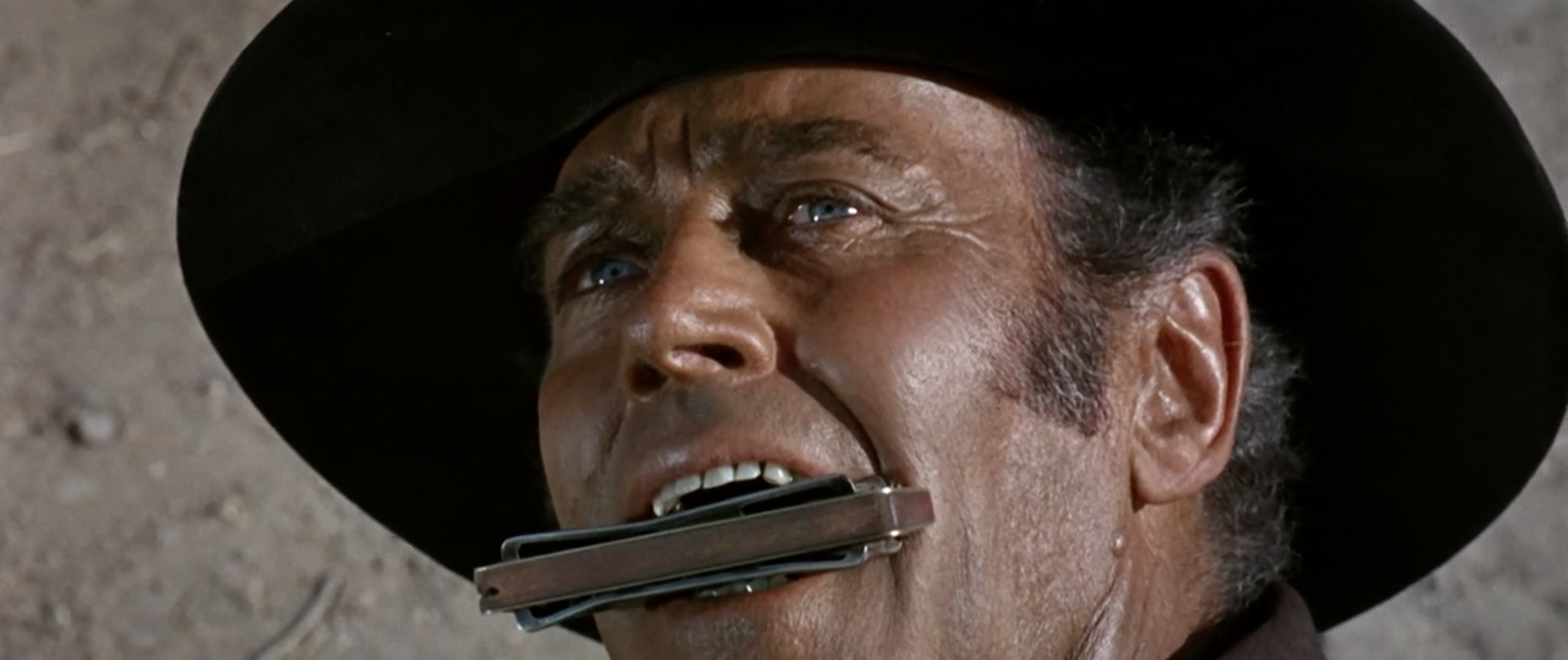

In the case of Teorema’s lonely aristocrats, it is not the secrets of God’s earthly creation which they must grapple with, but rather a mysterious figure who seems to come from another realm altogether. The Visitor’s eyes are a bright blue that seems to pierce the defences of whoever gazes into them, and at times he is even accompanied by a blinding sunlight forming a halo behind his head. The ease with which he falls into the family’s life is surprisingly intimate, but also offers them a strange emotional healing from their private insecurities.

When Emilia the maid attempts suicide with a gas hose, the Visitor rescues and consoles her. As Pietro the son lies in bed at night, his new roommate soothes his fears. Outside on the grass, he approaches the sexually frustrated mother Lucia sunbathing in the nude and wraps her in his arms. The immature young daughter Odetta invites him into her virginal white room, opening herself up to new experiences. And finally, the ailing father Paolo finds a comforting peace in his guest’s presence, as both walk along a misty river and talk among wild, overgrown bushes.

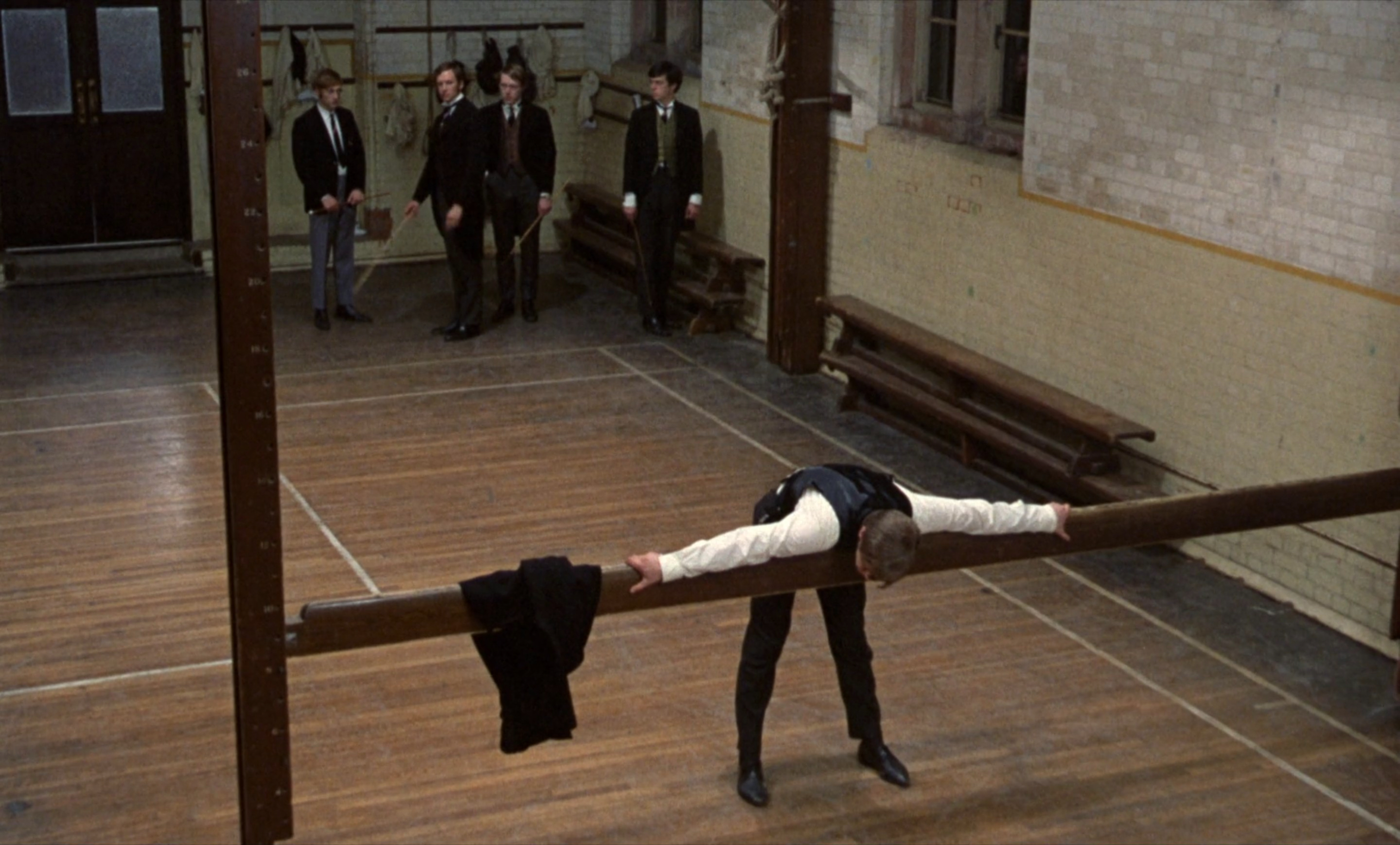

These are not merely innocent encounters, but Pasolini connects these characters’ spiritual awakenings to physical self-discoveries through explicit sexual seductions. As a result, each family member is individually bound to parallel journeys, methodically unfolding in the same, formulaic sequence established in the first act, and referenced in the film’s title Teorema – or ‘theorem’ in English.

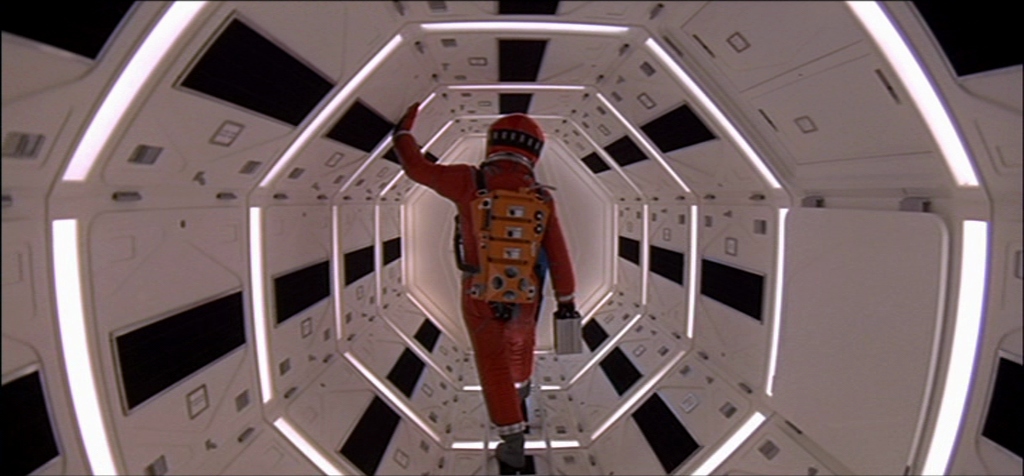

Following the announcement of the Visitor’s imminent departure, it is according to this order that Pasolini subsequently moves through their confessions in their respective locations. They have all faced the transmutation of their own souls, and now all they can do is contemplate the irrelevance of their old lives, and the uncertainty of their futures. “I no longer even recognise myself,” Pietro reflects in his bedroom. “I was like everyone else, with many faults, perhaps, mine and those of the world around me. You made me different by taking me out of the natural order of things.”

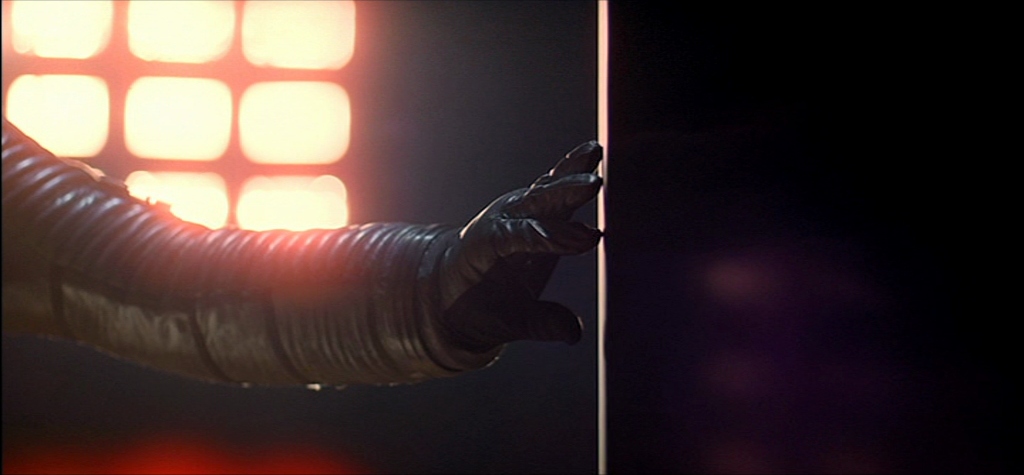

Out on the lawn, Lucia reveals the “real and total interest” the Visitor filled her life with during his stay, and inside Odetta expresses thanks for helping her grow up and explore her sexuality. As for Paolo, who has always believed “in order, in the future, and above all in ownership,” this guest has destroyed everything he understands about himself and the world. The only way he can imagine rebuilding his identity would be through “a scandal tantamount to social suicide,” separating himself from the materialism and ego of the modern world to seek a deeper truth in his existence.

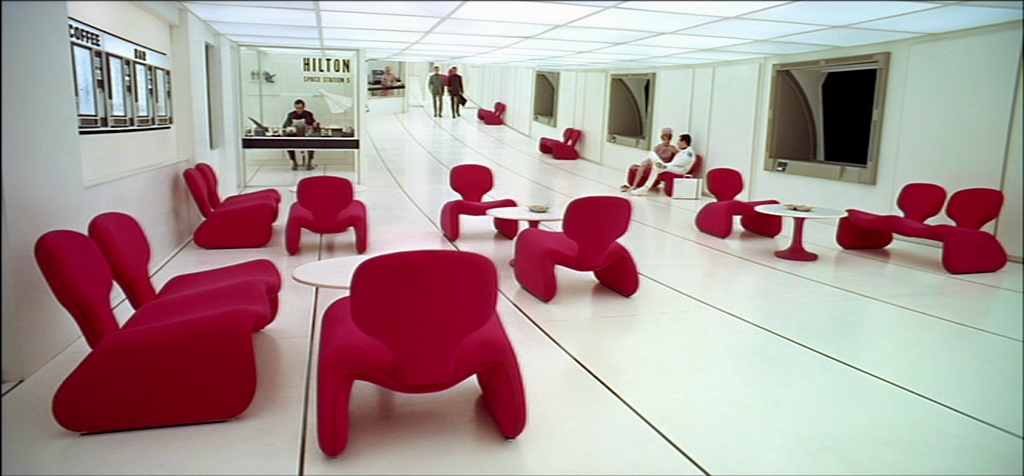

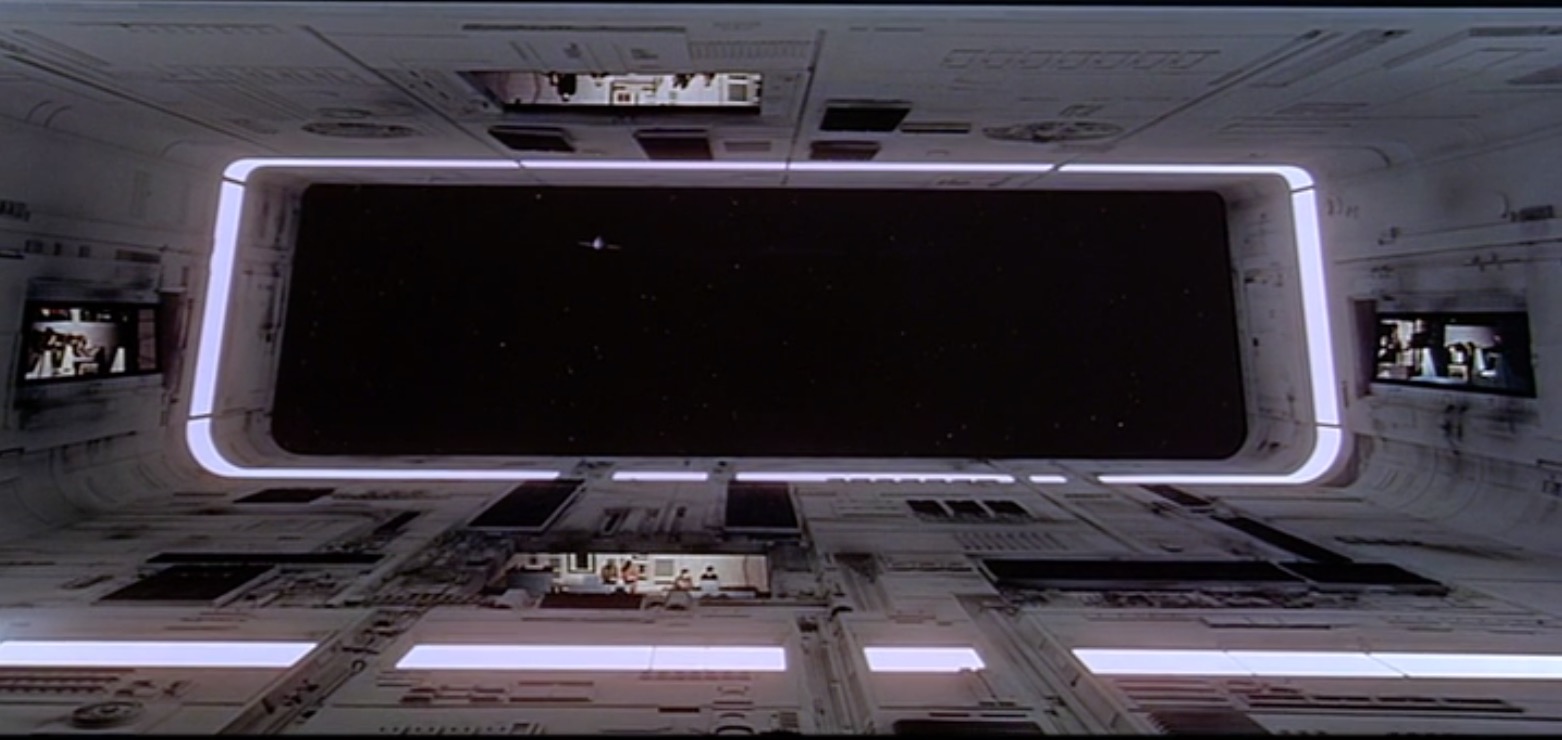

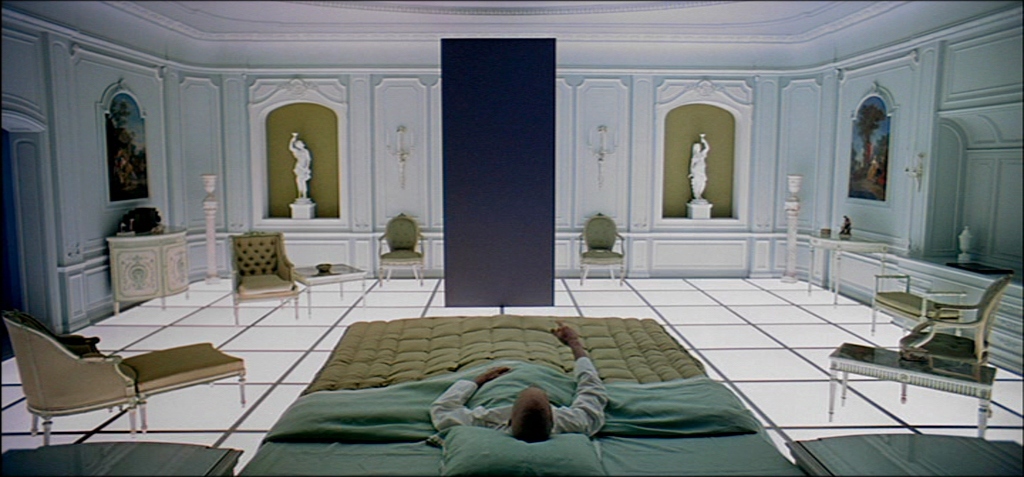

As for Pasolini’s stance on the sanity of it all, he approaches the matter with both delicate consideration and savage criticism. This wealthy family have been living a superficial lie for many years, consumed by worldly distractions and capitalist privilege, and so cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini infuses these scenes at their Milanese estate with a pristine fragility. Characters are blocked in rigorous arrangements worthy of paintings as they lounge on the lawn and seat themselves symmetrically around the dinner table, though these meticulous visuals carry a strange tension with Pasolini’s naturalistic, handheld camerawork. The stylistic contrast is unsettling, subtly detaching the family from the reality of the working class witnessed in the opening scene’s documentary footage, while containing them within a dream of sepia filters and ethereal green hues weaved through the mansion’s gates, lawn, cars, and décor.

Not that the extremity of their spiritual conversion is any less insane than the absurdity of their bloated privilege. Pasolini heavily implies that these nobles are so emotionally repressed they may simply be confusing the ecstasy of intercourse for divine revelation, further suggesting that the only two forces capable of tearing down oppressive class structures are sex and God – or at least, the unadulterated belief in them. Theological art and texts thus become ornamental in Teorema’s satire, displacing Ennio Morricone’s gloomy jazz score with Mozart’s haunting Requiem, and pondering Bible verses in contemplative voiceovers. Even here though, Pasolini is quoting the Book of Jeremiah to consider religion’s erasure of identity through sexual metaphors.

“You have seduced me, O Lord, and I have let myself be seduced. You have taken me by force, and you have prevailed. I have become an object of daily derision, and all mock me.”

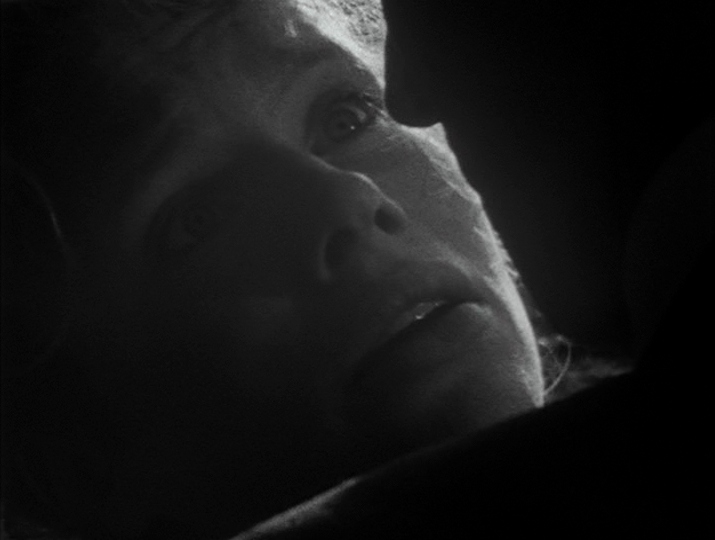

On one level, Pasolini is adopting the transcendent awe of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s films, gazing at impossible miracles of fasting, healing, and levitation performed by Emilia when she returns to her hometown. As the only main character here who belongs to the working class, she alone has the capacity to truly perceive and absorb the sacred, being unattached to the bourgeoisie’s material lifestyle. Her eventual sacrifice through live burial and self-immolation is even shot with an astounding beauty against the orange Italian sunset, capturing a glimpse of the sacred as she humbly resigns her body to the Earth.

Pasolini’s rigorous blocking of the family around Odetta’s catatonic state also visually alludes to the tragic funeral of a devoted believer in Dreyer’s Ordet, but there is no profound resurrection to be found here. The rest of this newly inspired family is as lost as ever, seeing Lucia aimlessly search for fulfilment through affairs with younger men, and Pietro express his lustrous longing for the absent Visitor through abstract painting. Art may be elevated in the eyes of upper-class society, but the son’s internal self-worth is thoroughly degraded as he recognises the lowliness and misery of any honest creator.

“Nobody must realise that the artist is a poor, trembling idiot, a second-rate hack who lives by taking chances and risks, like a disgraced child, his life reduced to the absurd melancholy of one who lives debased by the feeling of something lost forever.”

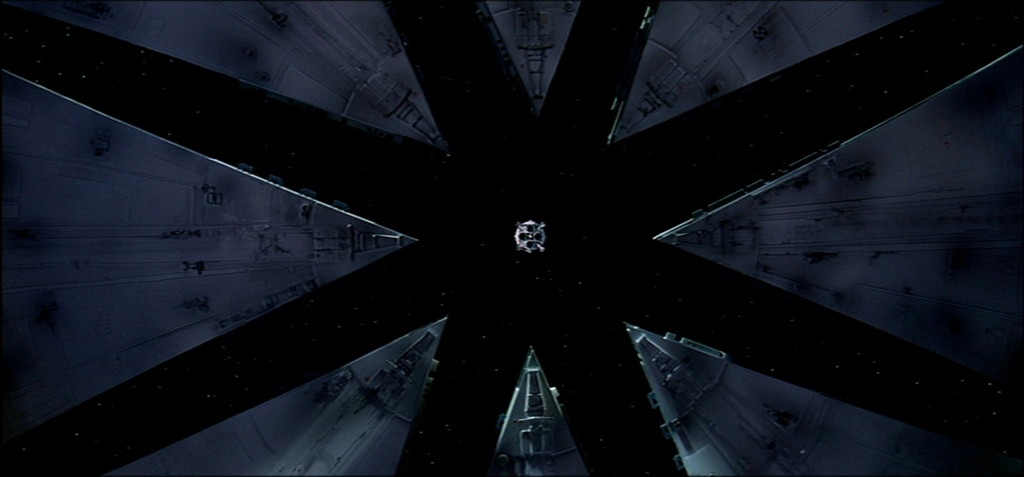

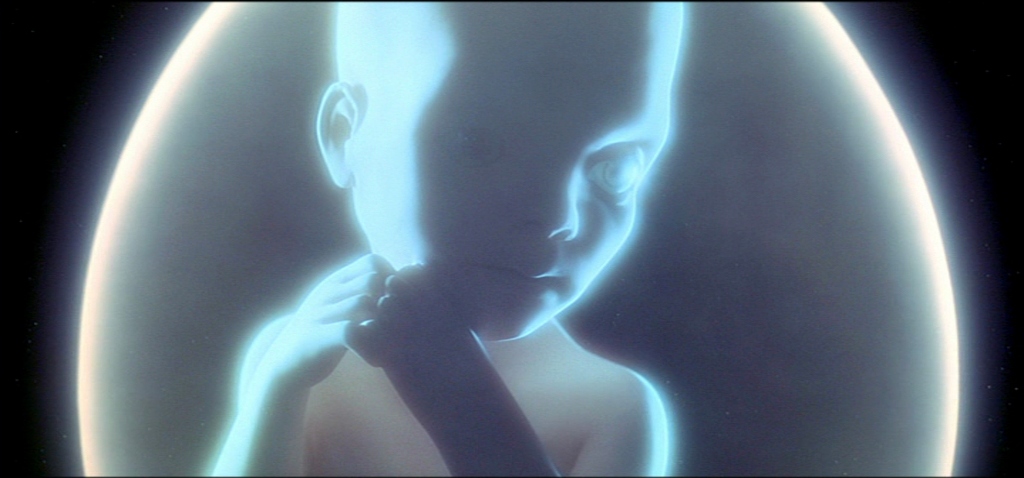

This extends further to the other members of this family who now spend their lives searching for an irrecoverable connection to a higher purpose, though perhaps Paolo understands the insanity of it more than anyone. Driven mad by his own empty existence, he enters a train station and strips himself completely nude, before handing the entire factory over to his workers. A victory is secured for Pasolini’s Marxist politics, returning the means of production to the industrial proletariat, while the black, desolate dunes of Mt Etna which have appeared intermittently throughout Teorema beckon a demented Paolo away from civilisation.

Unfortunately, whatever secrets the ancient volcano holds are inaccessible to this former capitalist, whose renunciation of all material possessions has only exposed his own hollowness. He runs through these landscapes in agony, as if trying to find some justification for his total sacrifice, but there is no power great enough to heal those souls eroded by pride and entitlement. Finally seeing themselves for what they are, all the bourgeoisie of Teorema can do is scream into a void that even God dare not touch, devolving into a state of repulsive, primal desperation that Pasolini knows can never be fulfilled.

Teorema is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the DVD and Blu-ray is available to purchase on Amazon.