Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 53min

Given how notoriously private Yasujirō Ozu was as a public figure, it is impossible to speculate with any certainty the reason why he never married. Considering that he was supposedly expelled from his boarding school for writing love letters to another boy, it is conceivable that he was a queer man living in conservative times. Alternatively, perhaps he simply valued his relationship with his mother over any romantic attachment, seeing as how he lived with her throughout his adulthood. His films never featured any surrogate characters explicitly representing him, and yet they were nevertheless a medium through which he deeply pondered those cultural Japanese traditions that he simultaneously was at odds with and adored.

With this context in mind, An Autumn Afternoon becomes all the more fascinating as Ozu’s last film in an incredibly vast career – not that he necessarily knew it would be at the time. His decline from throat cancer was sudden, seeing him pass away only a few months after his mother on his sixtieth birthday, leaving this as his final testament to the enduring purpose, duties, and conflicts of family and marriage. In its observations of a widowed father’s reluctant attempts to marry off his daughter Michiko, Late Spring’s narrative is specifically recaptured here, though the updated setting to 1960s also reveals Ozu’s complex relationship with the advance of Western modernity into Japanese civilisation.

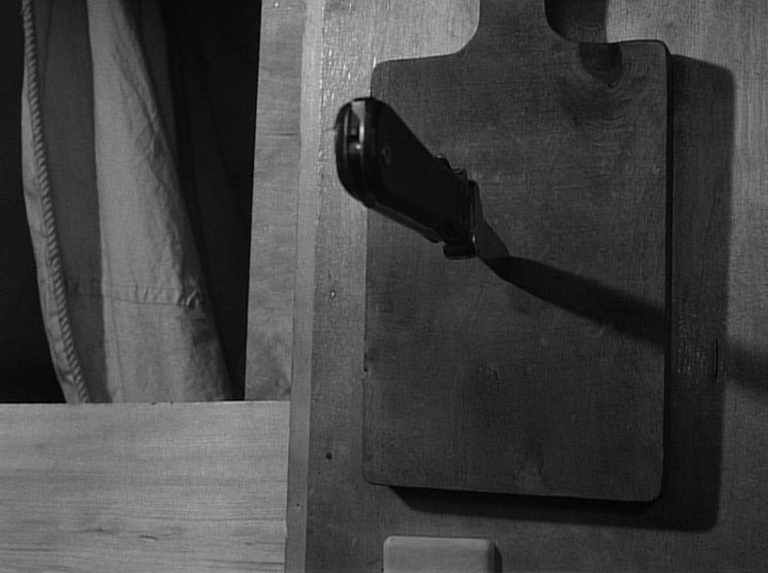

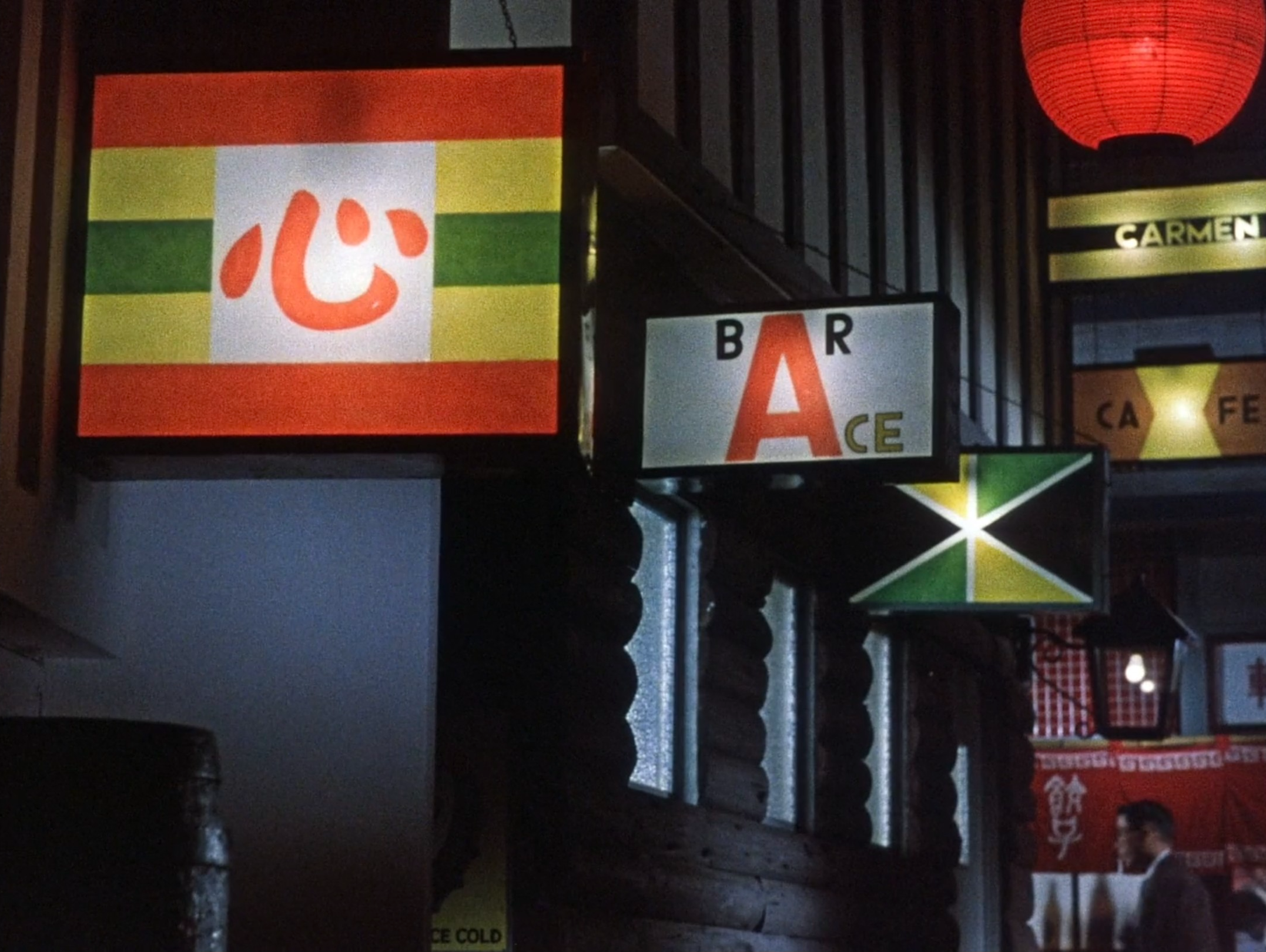

The pillow shots that herald the restaurant where Shūhei drinks with his friends consistently bathe in flashing signs and vibrant graphics that light up storefronts, poignantly recognising the shift to market capitalism that has been imported from America and Europe. Commercial indulgences are an irrevocable part of these characters’ lives, filling Shūhei’s companions with alcohol to the point of excess, and sparking arguments in his son Kōichi’s marriage over a set of golf clubs he desperately desires. Later, those same clubs are integrated into one of Ozu’s trademark hallway shots among other perfectly arranged household items, economically tying off this subplot and signalling a broader shift towards consumerism.

Above all else though, the colour cinematography which Ozu had begun using four years prior in Equinox Flower may be the strongest stylistic decision made in An Autumn Afternoon, vividly accentuating the organised patterns and contrasts that he had already mastered in black-and-white. While the interior architecture is handsomely captured with patterned wallpaper around shoji doors and geometric frames, it is more frequently the small props and ornaments which inject bursts of primary colours into his muted scenery, each set with absolute precision. At the restaurant, mid-shots of Shūhei and his friends are lined along the bottom with a full rainbow assortment of ceramic cups and saucers, while an impeccably composed wide shot leads a line of yellow bar stools towards an alleyway washed in neon red lighting. Even when there are no humans in sight, every vivid detail points to their presence, quietly littering pillow shots as beautifully simple as embroidered rugs draped over apartment balconies and empty slippers laying outside closed doors.

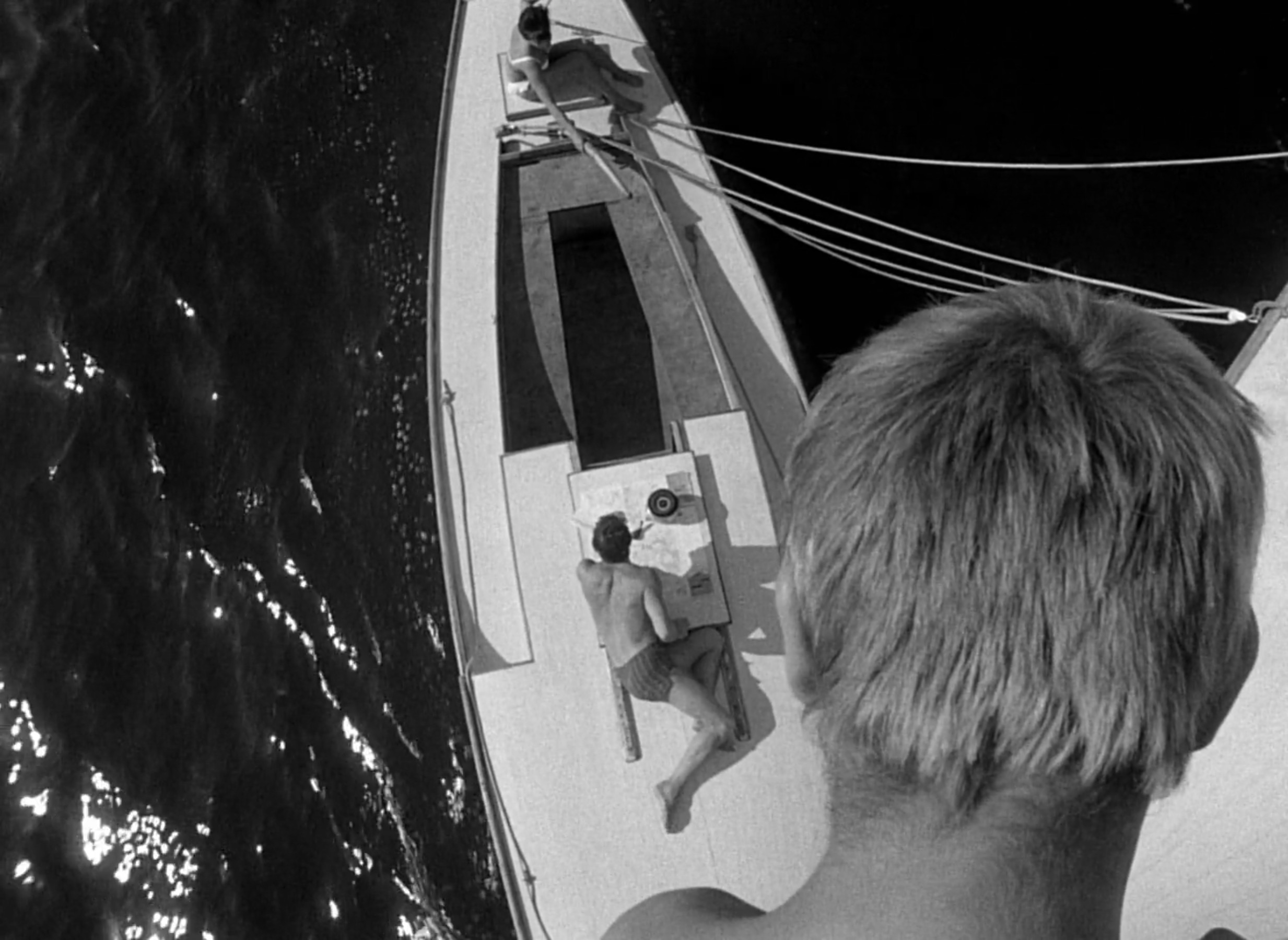

Most crucially, it is Ozu’s pairing of red and white which suggests a uniformity between Japanese tradition and industry in An Autumn Afternoon, mirrored between the striped smokestacks and steel drums of the very first shot. This palette continues to punctuate the mise-en-scène in sweaters, lanterns, and signs, before boldly arriving in Michiko’s elaborate white wedding gown and headdress accented with notes of crimson.

Visual patterns such as these are important to connecting the public and private lives of Ozu’s characters, further revealing the unity of the two in pillow shots that steadily cut between several frames associated with a new scene, and gradually edge closer to its characters. Quite significantly, this approach maintains a soothing, consistent flow in the editing, rather than falling back on the sort of establishing shots that a more conventional director might turn to. As a result, Ozu can recall these compositions as shorthand whenever he returns to a familiar location – the smokestacks viewed from Shūhei’s office window for example, or the surrounding restaurants outside Tory’s Bar.

Narratively, this formal poetry is also reflected through multiple characters who signal some shift in the status quo, underscored by the two instances of current and former naval officers mockingly sending up patriotic military anthems. Although Japan’s national spirit was broken after losing World War II and replaced with scathing cynicism among younger generations, Shūhei continues to mourn its loss, and sorrowfully responds in private with songs about floating castles guarding the Land of the Rising Sun.

Through the character of the Gourd, a respected teacher who mentored Shūhei and his friends on Chinese classics, Ozu continues to reckon with Japan’s changing culture by envisioning the future that awaits our protagonist should Michiko never marry. Not only has the Gourd’s middle-aged daughter become a lonely spinster due to his desire to keep her for himself, but his own life has also fallen into disarray by limiting her prospects, condemning him to run a cheap noodle shop and suffer humiliation every day from his customers.

The catalyst for the second half of An Autumn Afternoon’s narrative is thus set off, spurring Shūhei to secure a husband for Michiko. The fact that Ozu only dwells on the moments when her wedding finally arrives is telling of what he truly values within these cherished relationships, as a montage moves through the vacant home to dwell on a standing mirror, Venetian blinds, and a red-cushioned stool. These are domestic items that don’t hold dramatic weight on their own, yet peacefully evoke Michiko’s absence, and disappear from view as the camera cuts to a view just outside the window.

In the closing scene when Shūhei returns as an empty nester, Ozu frames him in a distant, wooden corridor of his last hallway shot, his back turned to the camera and slightly darkened by shadows. Ozu never inserted explicit representations of himself into his films, and yet Shūhei’s poignant resignation to change is one that this ageing director knows too well, having essentially spent the past thirty-five years recording Japan’s enormous cultural shifts on camera. If his life’s work is a cinematic suite testifying to the ongoing tension between tradition and progress, then An Autumn Afternoon makes for a tender final movement, resonating formal harmonies across generations to ultimately savour an undying faith in their shared humanity.

An Autumn Afternoon is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to purchase on Amazon.