Masaki Kobayashi | 3 parts (3hr 1min – 3hr 28min)

Sympathetic soldier, prisoner, and political pacifist Kaji seems to live multiple lives across the modern odyssey that Masaki Kobayashi lays out in The Human Condition trilogy. Through several years of Kaji’s time spent in World War II, he traverses virtually every inch of Manchuria in northeast China, bearing witness to experiences from all over the spectrum of life. Over time, encounters with birth, death, love, sex, culture, grief, conflict, faith, desire, and fear build towards a greater understanding of what it means to exist on Earth – and yet the wisdom Kaji is granted does not come with some enlightening inner peace. If anything, it only threatens the humanity which resides within him, as Kobayashi piles endless tests of moral endurance upon this man who strives for the betterment of society.

Few times in the history of film has a director adapted a novel with as sweeping majesty and creative invention as Masaki Kobayashi does here, rendering entire worlds of literary prose with astonishing cinematic magnitude. The Human Condition is an accomplishment of epic proportions, matched perhaps only by Gone with the Wind or The Lord of the Rings in its equal devotion to the source material and awe-inspiring spectacle. The title itself makes a promise of daunting philosophical scope which might seem more suited to an introspective drama than a war film, and yet Kobayashi’s harrowing examination of modern civilisation at its lowest manifests these abstract ideas on a pragmatically large scale. It is here in humanity’s darkest days that its most vital essence becomes both the strongest threat to widespread injustice, as well as its greatest target, turning Kaji’s soul into the last remaining battleground of moral fortitude.

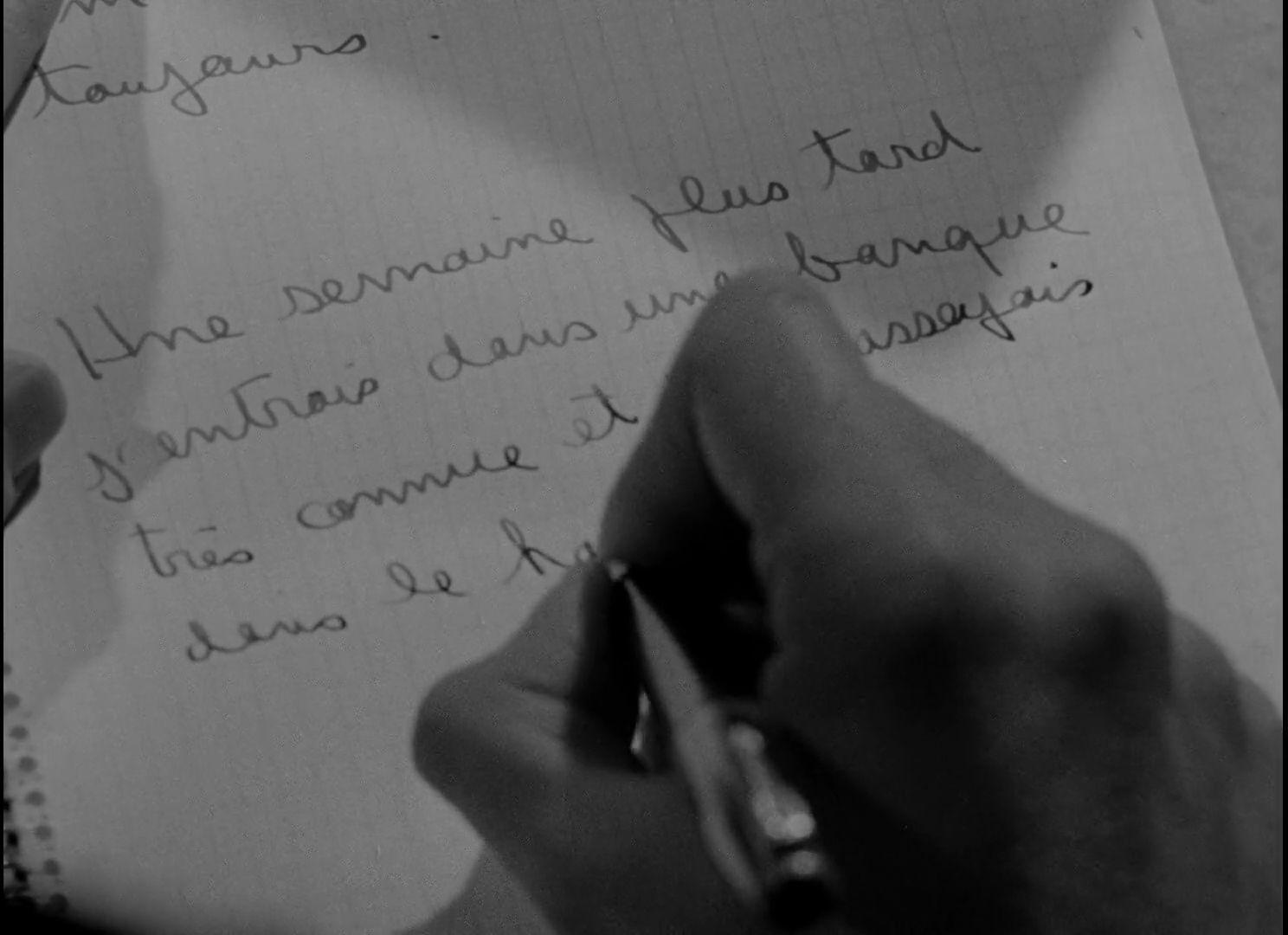

This 28-year-old idealist might not see it at the time, but these are the stakes laid out when he is first assigned to the role of supervisor at a slave-driven mining operation in Manchuria. Even the imperial Japanese authorities who place him there realise how little he is cut out for the job, and yet the report he has submitted against the exploitation of Chinese labour has nevertheless inspired them to send him off for a test of his naïve, pacifist principles. When he arrives with his newlywed wife Mochiko, he also comes with huge ambitions in tow – a revised employment system, improved working conditions, and rationing plans are just the start of it. “Take care of the men and the ore will come out,” he declares, practically bringing it all back a results-driven work ethic.

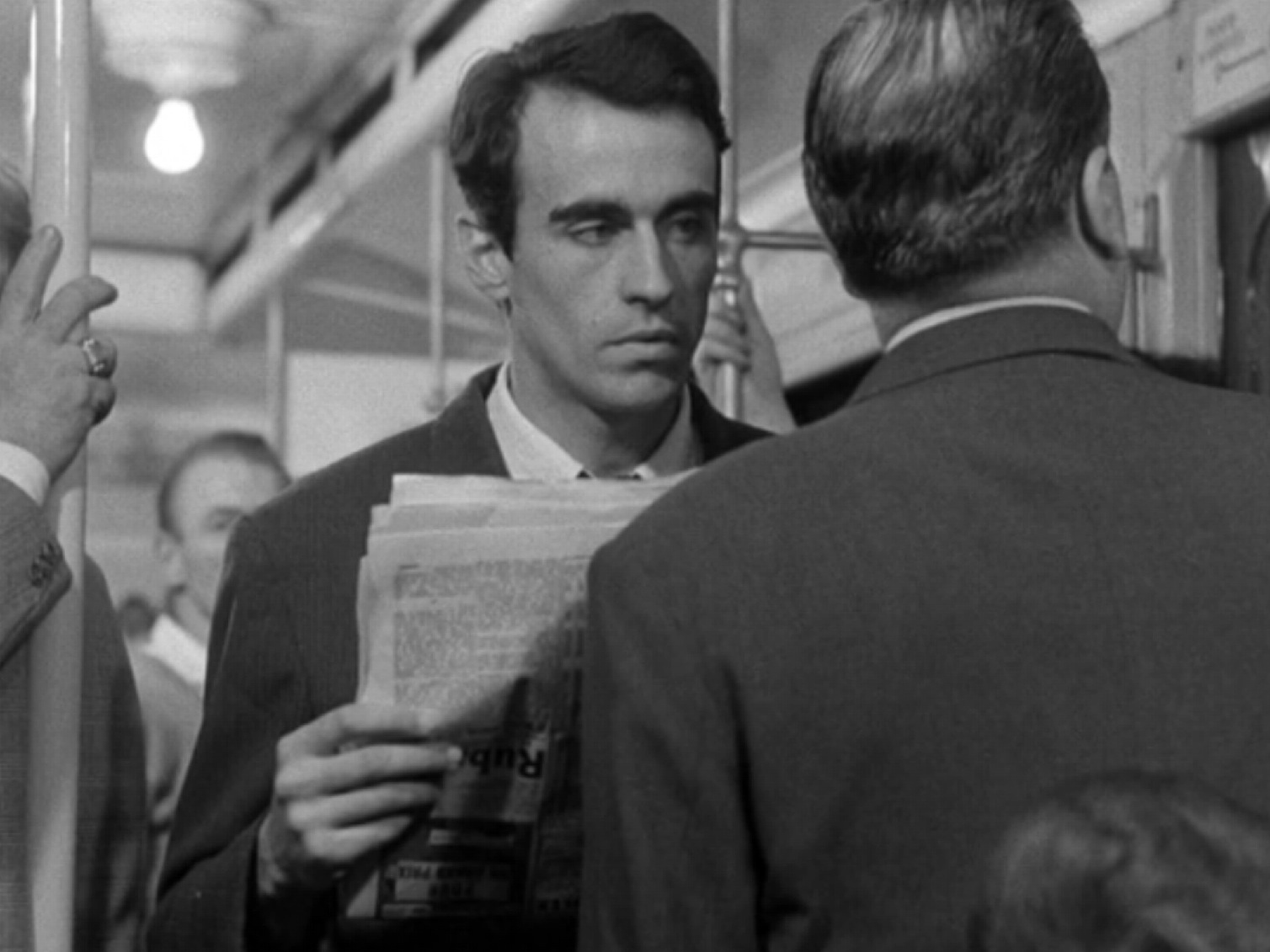

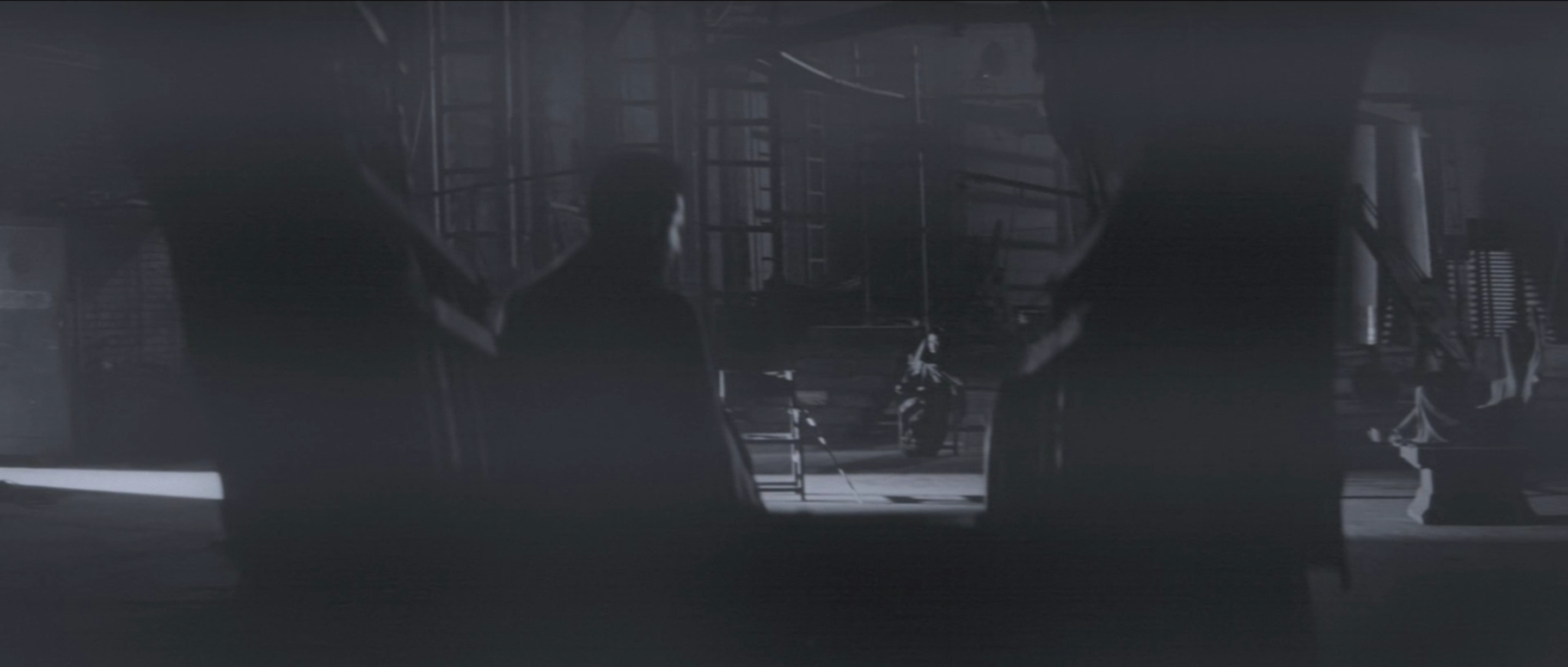

The delivery of 600 new ‘special’ workers who have been taken as prisoners-of-war becomes his first trial. The moment the train doors are unlocked, the gaunt, half-dead men come pouring out like zombies, swarming Kaji and his fellow administrators for any food or water they can get their hands on. That he is driven to violence as a means of control so early in this series immediately introduces a crushing hopelessness – if he can’t maintain peaceful leadership now, then what does this mean for him later when more pressure is inevitably applied? In the aftermath, it becomes apparent that 12 men died from overheating in the carriages, and 150 others escaped upon arrival. Failure is a companion Kaji will come to know very well in his journey.

Kobayashi has no reservations in landing us right next to him through these physical and emotional challenges either. Divided into three films respectively subtitled No Greater Love, Road to Eternity, and A Soldier’s Prayer, this ten-hour trilogy uses its length to gruelling effect, with each death and personal defeat accumulating in subtle increments towards a mountain of despair not even Kaji can bear.

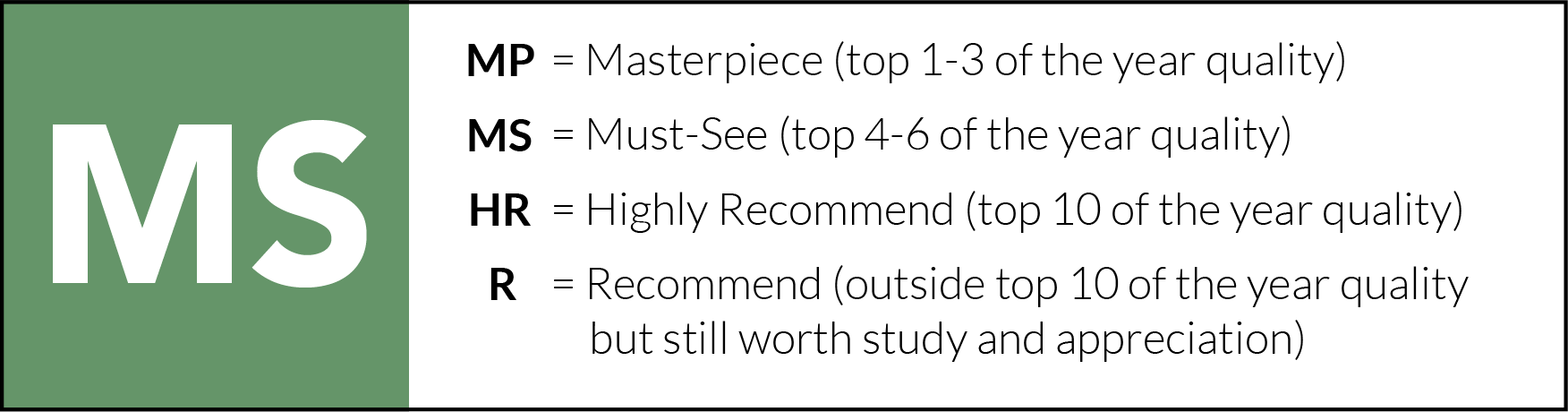

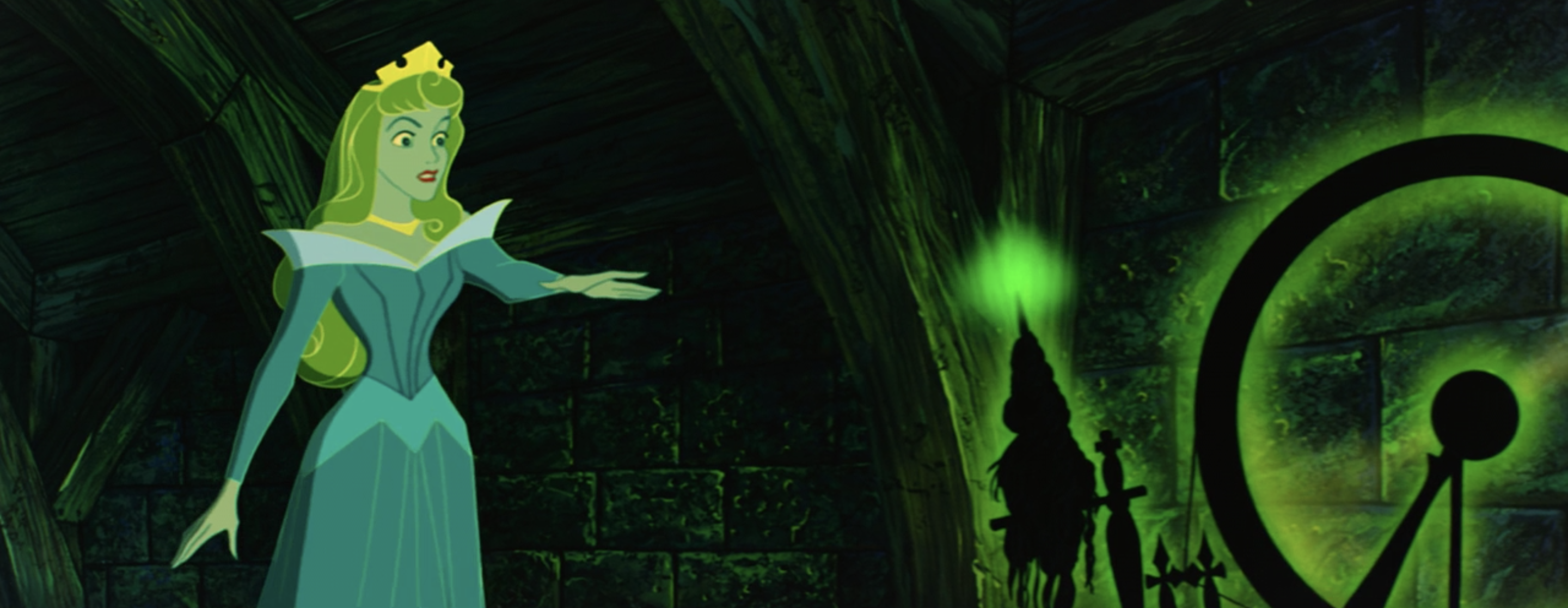

Perhaps even more crucial to the vivid experience of The Human Condition than its scale is Kobayashi’s bleak, rugged photography, advancing in stylistic virtuosity with each film. Though not as widely recognised as his Japanese contemporaries Akira Kurosawa or Yasujirō Ozu, his mastery of visual composition through blocking rivals both, even as he is largely working with stark, desolate landscapes. A total dedication to building out the background of even relatively minor scenes consistently shines through the trilogy, connecting Kaji to hostile environments and enormous crowds of extras. In the labour camp setting of the first film, watchtowers frequently loom over him in low angles as he talks through barbed wire to embittered prisoners, always keeping that constant surveillance in the back of our minds. As these men are sent off to work at the mines, Kobayashi lines hundreds of them up in zig-zag paths across rocky hilltops and valleys, and pans his camera along their enormous trail from one horizon to another in a single magnificent shot.

When Kaji departs the labour camp and is forced to serve in the Japanese army, the harshness of Kobayashi’s scenery continues to transform, pitching him against new threats within yet another corrupt institution. The depth of field present in his cinematography impresses even more when we find ourselves in army camps, its rough interiors lined with wooden bunk beds upon which soldiers are staggered across all levels of the frame. The power dynamics are evident in this staging – much like at the labour camp, Kaji is ostracised for his Communist-adjacent politics, while other recruits like the similarly rebellious Shinjo and the meek Obara also find themselves targeted by their more nationalistic peers.

This instalment, Road to Eternity, clearly sets a standard of war film which would echo through history, especially providing the inspiration for Full Metal Jacket with its bifurcated structure split between boot camp and the battlefield. The suicide of the deeply tormented Private Pyle in Stanley Kubrick’s film mirrors Obara’s here too, though this death carries a tinge of bitter irony when the rifle’s misfire inspires a renewed desire to live – “Is that a sign that I shouldn’t? Yes! After all, one can die at any time” – before incidentally killing him a few seconds later.

Kobayashi’s dark sense of humour is clearly integral to his approach of such weighty material. The cruel fate which drew Obara to his tragic end is the same which leads virtually every other character along winding roads towards their inevitable destinies. For Kaji especially, there is a circular poetry to his journey that transforms him from a supervisor of a Japanese camp to a prisoner in a Soviet camp, inflicting the same inhumane punishments against him which he once sought to combat.

Kaji’s integrity has been tested many times up to this point, even seeing him brutally murder a fellow Japanese soldier to keep his hiding spot, and yet this is the first time his Communist sympathies are directly challenged. When he tries to express them to his captors, he comes up against a language barrier that the corrupt translator ensures stays in place, and the political hypocrisy of those in charge similarly weakens his resolve. The theoretical equality of this supposedly classless ideology is nowhere to be found in this punitive, hierarchal institution, and Kaji’s impassioned monologue towards those Soviets he once expected to be allies falls on deaf ears that cannot understand his Japanese.

“In your urgency, supervision grows slack. You stick to inflexible rules. Good intentions are suppressed, and evil is tolerated. The fact that socialism is better than fascism isn’t enough to keep us alive!”

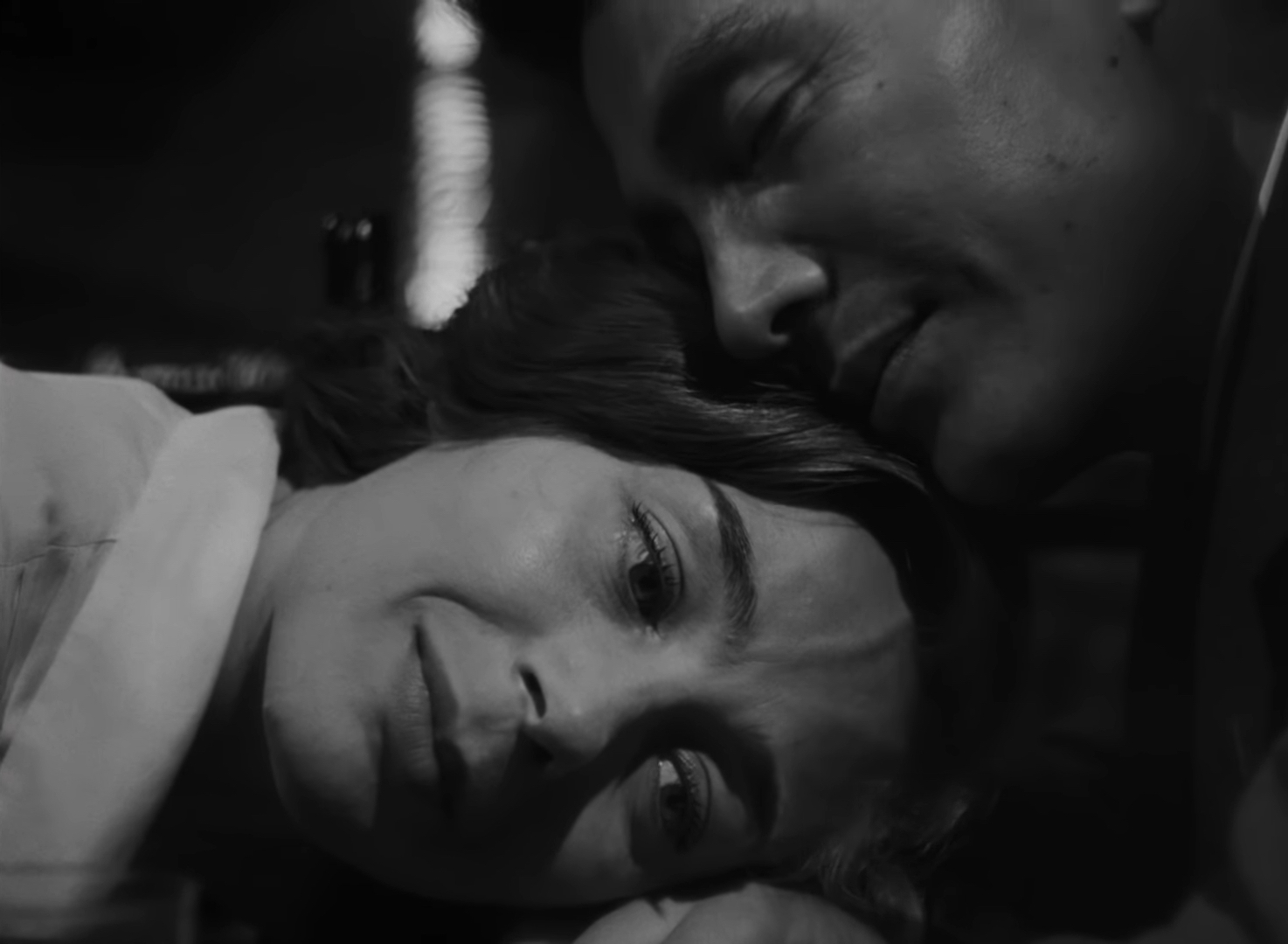

In environments as aggressive as this, even the most basic human communication cannot function, leaving those who do share some level of understanding to bond on more intimate levels than normal. Therein lies another key aspect of the ‘human condition’ – the desire to seek companionship effectively becomes a form of emotional starvation in times where common empathy is lacking. For Kaji specifically, it is his love of Mochiko which remains his core motivation when all his principles are stripped away, but even he feels the lure of extramarital attraction in her absence. A sweet but fleeting connection with a nurse in a military hospital almost develops into an affair, yet simply ends on friendly terms with him teasing the possibility that they might see each other again.

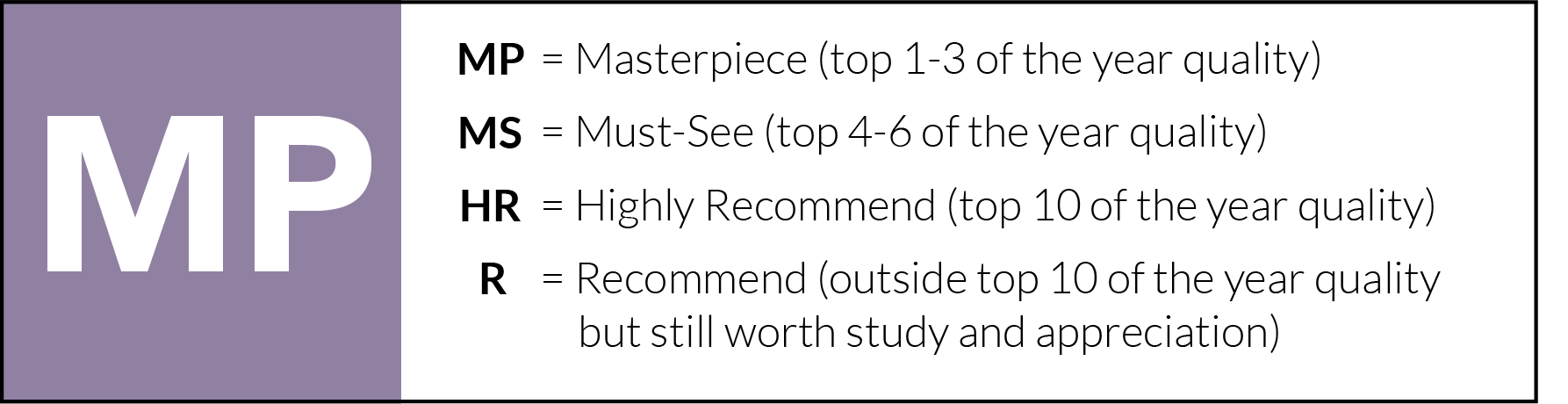

This is no romantic Jacques Demy musical though, bringing distant lovers together by whims of fate. Every scene of intimacy in The Human Condition hinges on the understanding that anyone could potentially die at any time, and that this moment of ecstasy may be all they have left. Hearing that prostitutes will be visiting the camp ignites joy in the Chinese prisoners of the first film, and the alliance built between those men and women fosters some of the strongest relationships of the entire series, with both working together on multiple escape attempts.

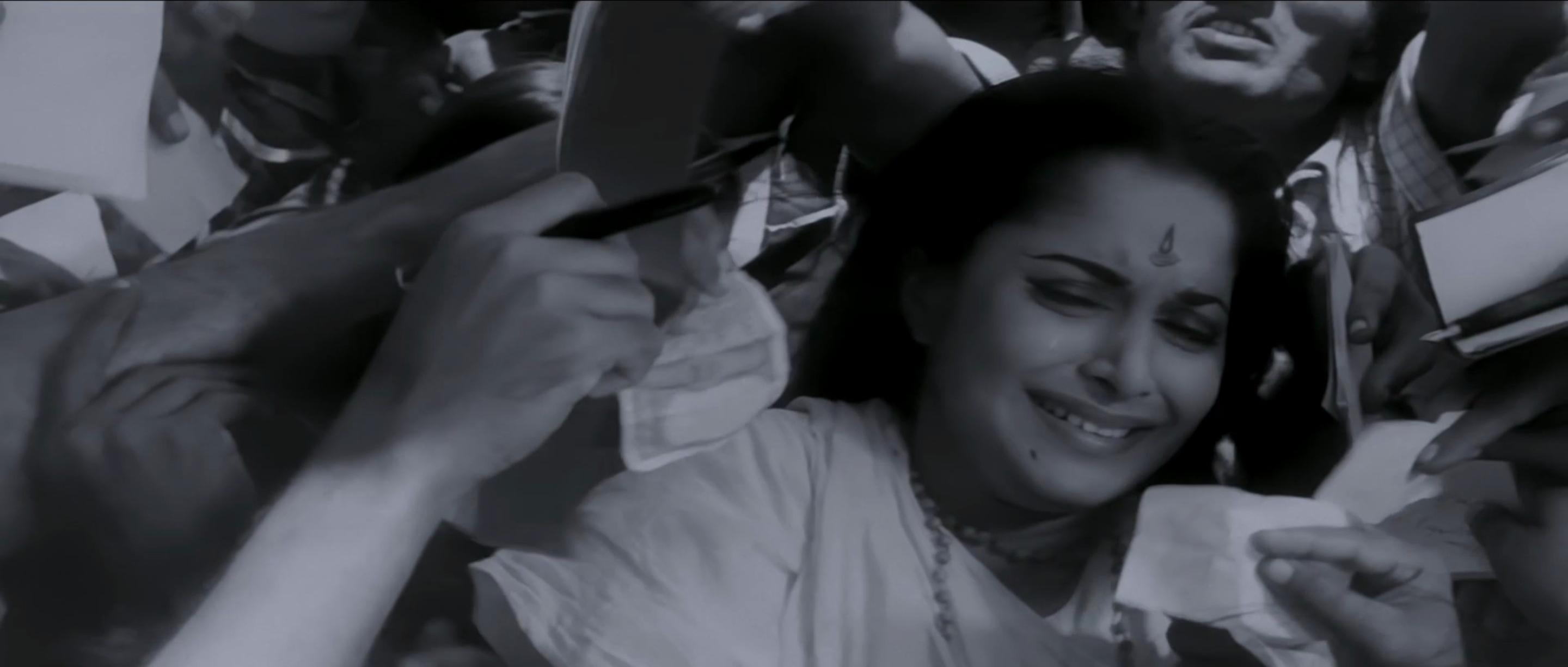

Later when Kaji abandons the army and finds himself leading Japanese refugees through dangerous forests and wastelands, Kobayashi orchestrates yet another profoundly affectionate scene between those whose lives have been destroyed. As most of the men and women make love in a farmhouse, Kaji sits by a campfire with another woman seeking warmth. Sensing his judgement of those inside who are married, she mounts a poignant defence of them, while Kobayashi sensitively dollies his camera slowly in on her face.

“Even if we get home alive, how many of us can return to our former lives? When women and soldiers spend fleeting nights together, they always talk about returning home together. When flesh meets flesh, it really seems possible. But at dawn the soldiers are strangers again. They get restless and anxious and grab their weapons and sneak off.”

At this point her monologue turns into voiceover, as Kobayashi detaches his camera from the conversation and starts moving it into the farmhouse. A single, parallel tracking shot glides across a row of beds, upon which bodies wrap around each other in sexual embrace, and yet whatever pleasure we expect to find is muted. As she mourns their collective futures, a faint sob can be heard in the background, and a montage unfolds of their distraught faces crying into each other’s arms.

“We’ll never get home. We’ll never see our loved ones again. We don’t even know how long we’ll live. We all share the same fate. We’re all ruined. We eat only to keep our strength from failing.”

For a director so dedicated to epic imagery, Kobayashi is notably skilled at depicting the psychology of his characters, entering the deepest recesses of their mind. Close-ups like those in the farmhouse offer a glimpse into emotions shared by entire communities, but within Kaji’s own story too we often get voiceovers of his immediate thoughts paired with Tatsuya Nakadai’s haunted, wide-eyed expressions. His performance is nothing less than breathtaking, especially when one considers where it starts and finishes, mapping out the erosion of every belief that defines Kaji as an individual until all he is left with is a single, primal desire to return home. Hatred gradually settles into his soul, and finally wins out in one of the trilogy’s greatest shots that smothers his face with darkness, leaving only a thin sliver of light to illuminate the bitter anger in his profile.

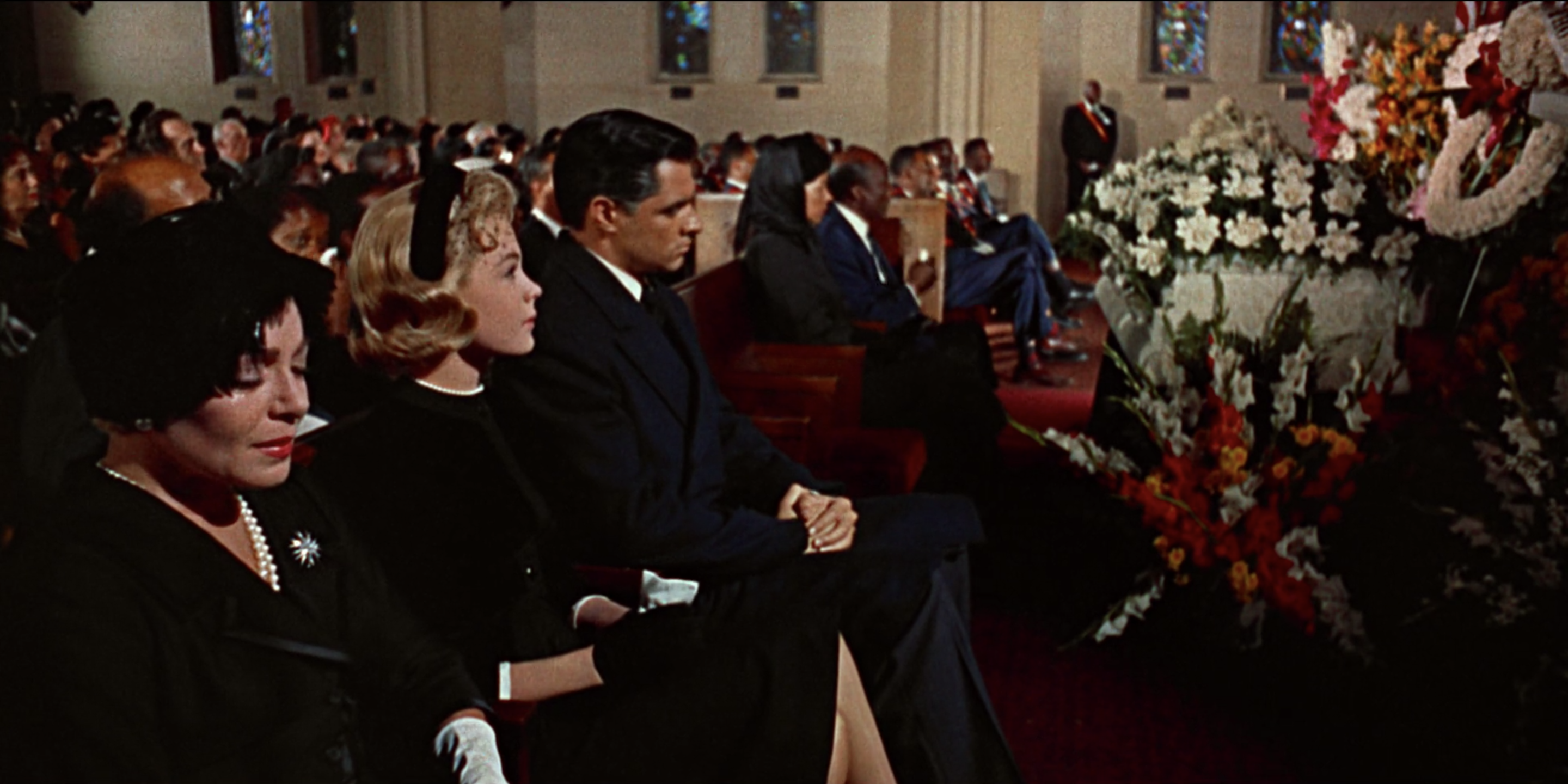

Once Kaji’s mind is infected with the madness of war, so too does Kobayashi’s cinematography throw its axis off in chaotic canted angles. After a devastating battle which unfolds like a horror film in Road to Eternity, Kaji ventures into the wilderness in A Soldier’s Prayer with a few troops by his side. For the first time he finds himself beyond the reach of any corrupt institutions, and instead bucks up against the devastating power of the natural world. Tilted tracking shots stumble with them in total exhaustion, bearing resemblance to similar visual devices innovated by Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov from around the same time, as delusional voiceovers echo through his mind.

It is an incredibly effective technique that Kobayashi touches several other times in this trilogy, most notably during the execution of Chinese prisoners-of-war after an attempted escape. Kaji’s world is totally tipped off-balance as he kneels beside them in agony and empathy, looking almost like he too is condemned to suffer his own parallel spiritual death. Kao is the only one among them to put up a fight in furious protest, and when he too eventually gives in, Kobayashi physically moves the camera to straighten out his final canted angle as if in quiet resignation. “This is your true form. The face of a man, the heart of a beast,” Kao spits at the hopeless Kaji before his demise. These words cut deep, ultimately spurring Kaji to take the moral high ground against his fellow Japanese – but for what? The purity of his own soul? His courage is admirable, but the actual change he can affect is minimal.

Then again, perhaps the inspiration expressed by a colleague upon his departure from the labour offers some justification. It is but a tiny spark of hope in a series that shows us time and time again the powerlessness of individual morality. Even as Kaji trudges through distant, snowy fields in his final days, utterly drained of those ambitions and convictions which defined him as an individual at the start of The Human Condition, he is fuelled solely by the last remaining shred of his humanity which could not be destroyed – his love for Michiko. It persists in hallucinations of her elated voice welcoming him home as Kobayashi frames his frozen, bearded face against dark, angry skies, and drives him right up to his final steps.

In the end, it is Kaji’s body which gives up before his spirit. Perhaps this is the core of the human condition, Kobayashi posits, finally distilled into its purest form – a desire for goodness persisting not for some moral high ground, or even in some false belief that it will reliably prevail over adversity, but simply because it is our most base, natural instinct. In this moment, every minute of Kobayashi’s epic, ten-hour trilogy can be viscerally felt, and we are left with nothing but the lifeless remains of humanity destroyed by the very same war it created.

The Human Condition trilogy is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.