Luchino Visconti | 1hr 55min

There is a strange blend of neorealism and comedic satire in Bellissima which, at first glance, Luchino Visconti only seems half-suited to. As a forefather of the Italian movement in the 1940s, his stark, grounded direction never falters, and yet at the same time he is not a filmmaker known for his sense of humour. It is surprising then to see just how well he formally unites both in their shared inclination for social criticism, aiming them towards a mutual target – the ludicrous glorification of a cruel, exploitative entertainment industry. The rigorously blocked compositions that bring rich visual detail to his greatest films are scarce, but within the studio backlots and working-class suburbs of Rome, Visconti identifies an authentic connection between the pursuit of one effusive show mum to make her daughter a star, and her struggles of post-war poverty.

In what appears to be Anna Magnani’s effort to collect distinguished Italian directors from Rossellini to Fellini, her illustrious career intersects with Visconti’s here, ticking him off her list with a performance that swings from amusing parody to heartfelt poignancy. Maddalena is not a perfect mother, but she is deeply passionate, and when a casting call is sent out for a new film by Alessandro Blasetti, she joins the crowd of zealous parents trying to book their children a spot for the lead role. One might almost think these masses of working-class people were fighting for rations the way they elbow each other to the front, doing everything in the power to rise above the others.

It doesn’t stop there for Maddalena though – the arrival of veteran actor Tilde Spernanzoni on the scene brings promises of coaching her daughter, Maria, to the highest standard, and yet even here this coddling mother can’t help but call her own inexperienced feedback from the apartment window. When she learns from a rival parent that the character in the source material was a ballerina, she enrols her daughter in ballet classes as well. As it turns out, there’s no actual dancing required for this role, but a little girl in a tutu is too cute for movie executives to turn down. In effect, these children must be moulded into images cut for them by popular culture, as only then can they be considered successful. Visconti milks the comedy from this premise for a while too, throwing another comical obstacle into the mix when a boy mischievously cuts off Maria’s pigtails, though eventually Maddalena winds it all back, solemnly reminding us of the desperate insecurity underlying her misguided efforts.

“I want my daughter to become somebody.”

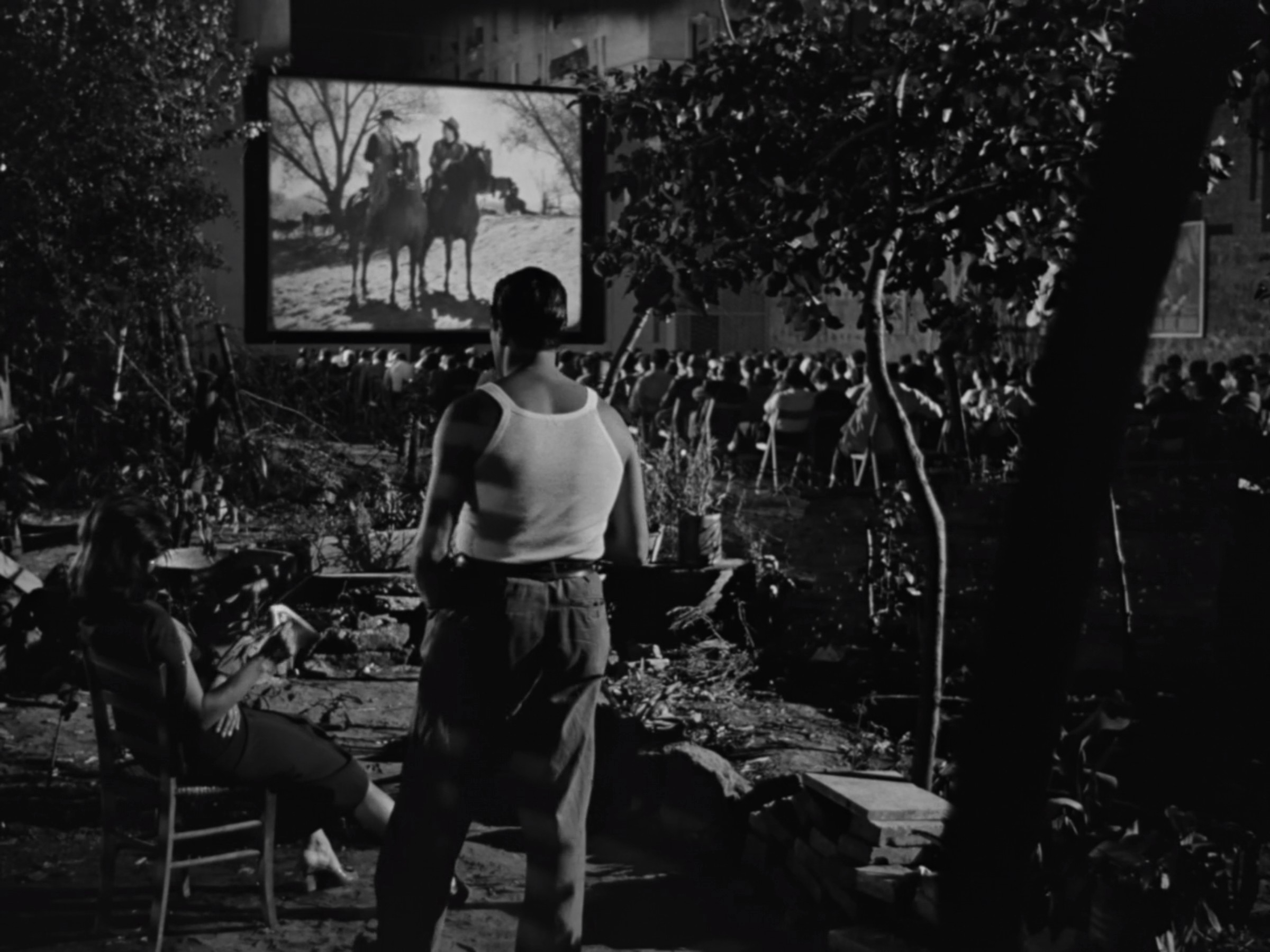

For the struggling lower classes of post-war Italy, movies represent everything they don’t have. With regular screenings in the square just outside Maddalena’s apartment building as well, they are virtually inescapable. American imports are particularly popular, as Red River projects fantasies of the Old West up in front of huge crowds, and the voice of Burt Lancaster penetrates the walls of Maddalena’s own apartment. As Visconti pans his camera around the destitute courtyards and streets surrounding her home, it is easy to see why the glamour of show business is held in such high regard here. Perhaps the only thing that would be more crushing than the state of her current life would be the realisation that her exceedingly ordinary daughter doesn’t possess that much talent after all.

Despite meeting with a film editor and former star who fell into obscurity after nabbing a few decent parts, Maddalena still refuses to recognise the cruelty and difficulty of the movie industry, leaving the heartbreak to sink in all at once when she peeks inside the screening room where casting directors watch Maria’s audition. Not only does her daughter’s incompetence as an actress become entirely apparent, but these executives don’t even try to hold back their callous laughter, calling her names without realising that her mother can hear everything. Magnani’s face crumbles in close-up as she is pulled back down to earth, finally seeing the futility of all her sacrifices.

If Visconti’s narrative disengages from reality at any point, then it is surely in the miraculous change of heart the casting directors experience upon watching Maria’s reel a second time, where they apparently discover hidden, unconventional talent. For Maddalena though, it comes too late. Her daughter needs to live on her own terms rather than those written out in exploitative contracts, and she deserves greater stability than that which the fickle movie industry can provide.

“I didn’t bring her into the world to amuse anyone.”

As the satire and naturalism of Bellissima’s narrative equally resolve, there are greater things in the world to aspire to than pure entertainment. This may be a strange mix of film conventions, and yet in its earnest consideration of parental ambition, both Visconti and Magnani prove their own impressive versatility as neorealist innovators.

Bellissima is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.