Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 46min

When the rock at the centre of the Toda family is lost, there is little that remains to hold its fragments together – though the enthusiastic attendance of Shintarō’s 69th birthday celebrations might originally suggest otherwise. Surely his children would loyally support each other after his passing, and they would certainly never try to palm off their now-homeless mother and youngest sister Setsuko, effectively washing their hands of responsibility. For those who comfortably belong to Japan’s upper-class though, family ties are diminished by their lack of interdependence, and Yasujirō Ozu’s filmic foray into the stratosphere of the elite exposes the true weakness in their relationships.

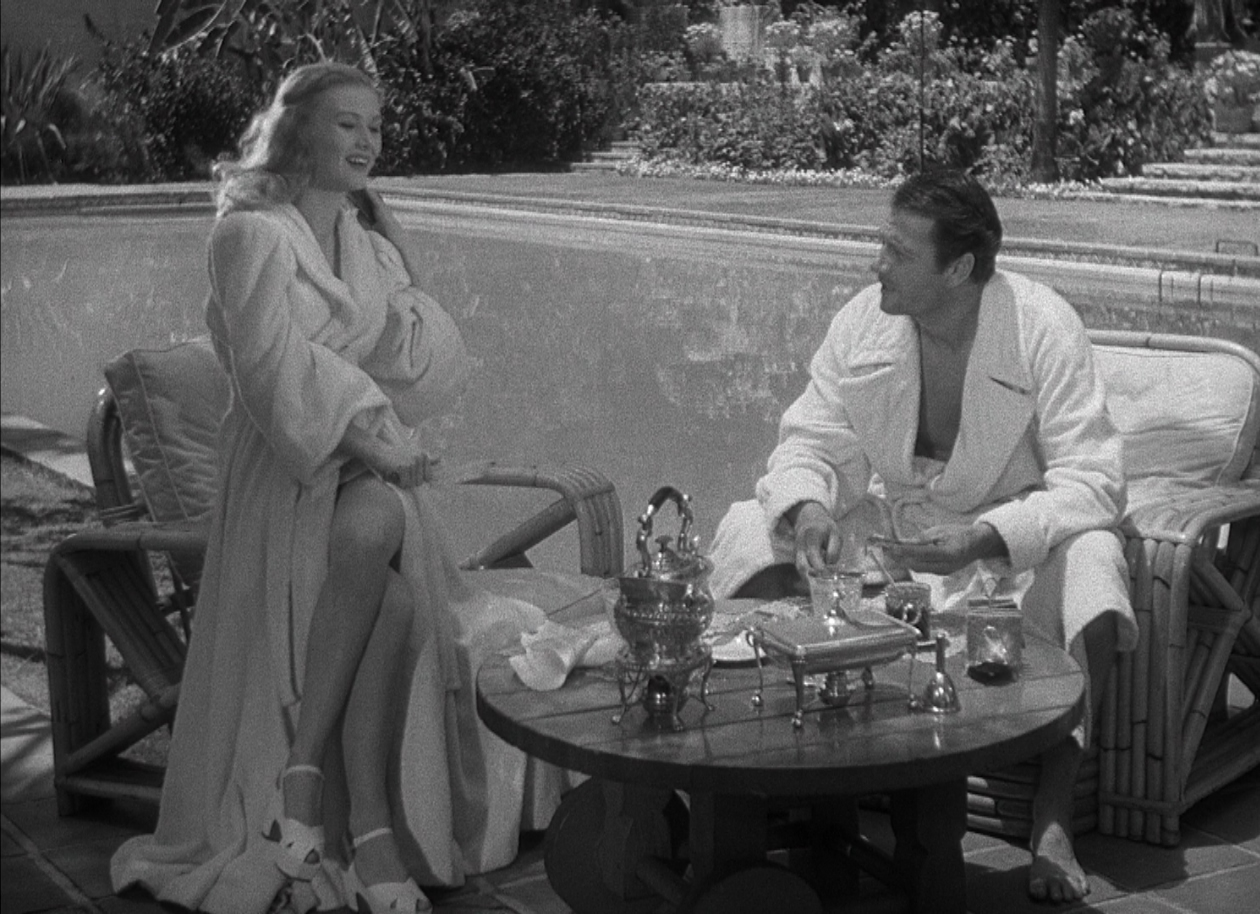

With his focus shifting away from society’s disenfranchised, the personal conflicts in Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family stem more apathy than the insecurity of Ozu’s previous characters, marking a notable departure from the industrial wastelands of The Only Son or the provincial streets of A Story of Floating Weeds. Perhaps this break from rundown locations is partly why its visuals are a little more muted, but it’s tough to criticise his mise-en-scène too much when it still bears the markings of his carefully set interiors. Here, patterned wallpaper forms delicate frames around doorways, while abundant flowers densely crowd out compositions at Shintarō’s funeral, commemorating his life through immoderate displays of wealth.

It is at Shintarō’s birthday party though where we get our first taste of this family’s decay, revealed in pillow shots which follow his initial collapse and move into an empty doctor’s office. There, a grandfather clock rhythmically swings its pendulum with the repetitive, ringing telephone, marking the first of several instances that Ozu calls upon this symbol of time and mortality – not that the Toda children necessarily consider the weight that either bear on their lives. Apparently the cultural tradition of honouring one’s elders only applies to the underprivileged who continue to lean on them, and even after being wracked by Shintarō’s post-mortem debts, still these siblings dedicate the bare minimum to looking after their mother.

When Mrs. Toda and Setsuko move in with the eldest brother Shin’ichiro, disharmony finds fertile ground, eventually sprouting into a confrontation between his wife Kazuko and Setsuko. Quarrels in Ozu films are rarely impassioned, yet resentment simmers in glacial accusations, beginning with Setsuk’s simple request that Kazuko avoid playing piano while she and her mother are sleeping. Kazuko is seemingly happy to oblige, but not without questioning why they didn’t greet the guest they had earlier that day, openly laying out her disdain for all to see.

Perhaps then peace will be found living with the eldest sister Chizuko, but when Setsuko expresses her desire to get a job, she is chastised for even considering the disgraceful notion of joining the working class. Elsewhere in this household, Chizuko’s resistance to disciplining her rebellious son sparks a clash with her mother, and ends in Chizuko sharing perhaps the harshest words of the film.

“Just stay away from my son.”

With this arrangement failing as well, Ayako is next to reluctantly offer her home, so she is relieved indeed when a frustrated Mrs. Toda resolves instead to reside in the family’s only remaining property – a rundown house by the sea. If there is any redemption to be found among the Toda siblings, then it is through the final sibling Shōjirō, whose move to China shortly after his father’s death has largely insulated him from these affairs. Upon his return for the one-year anniversary of Shintarō’s passing, he effectively becomes Ozu’s mouthpiece, scolding each of his siblings for neglecting their gracious mother. His home in China is not ideal given its distance, but it is nevertheless a safe place for his mother to relax and Setsuko to find work, free from judgement.

Rarely does Ozu take so firm a stance on the tension between tradition and modernity as he does in Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family. Shin’ichiro, Chizuko, and Ayako may not be villains, but the shallowness with which they approach their personal responsibilities brands them hypocrites in his eyes, holding the foundations of their privilege in little esteem. Prosperity is evidently not the measure of family bonds in this cutting class critique. Through grief and adversity, the hollowness of their affluence is laid bare, and reverent devotion for one’s roots holds on by a single, resilient thread.

Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.