Jean Renoir | 1hr 50min

The social conventions that govern the lives of Jean Renoir’s ensemble in The Rules of the Game may be binding laws within a certain stratosphere of French aristocracy, but they are to be taken with a grain of salt. These are arbitrary customs, designed to create the façade of honour and dignity, rather than truly encouraging the adoption of such lofty ideals. “I can’t run off with the wife of a host who calls me friend and shakes my hand without an explanation,” Andre explains to Christine, despite him spending much of the film prior to their conversation doing exactly this. “There are still rules.”

Perhaps then the most significant rule of all is one that is entirely unspoken – as long as the adultery and back-stabbing takes place away from the eyes of others, then this behaviour is perfectly acceptable. Renoir’s critique of such hypocrisy has a sharp edge to it, undercutting the egos that entangle themselves in a web of affairs over one weekend at the country estate La Colinière, owned by the Marquis de la Chesnaye, Robert. The irony that he himself is cheating with his mistress Geneviève is lost on him when he discovers hints of a romance between his wife, Christine, and his friend, Andre. Complicating matters further is the parallel drama unfolding among the servants of the estate, with Christine’s maid Lisette being sought after by both her jealous husband, Schumacher, and the newest worker to join the fray, Marceau.

Any pretensions that the upstairs folk of this estate are somehow more refined than those downstairs are thoroughly eroded in Renoir’s formal comparison. His deep focus serves an economic purpose here in shots that play out Christine’s drama in the foreground, while men squabble over Lisette’s heart in the background, drawing a hard line between the two social classes that should never romantically intermingle. Even when Robert eventually makes up with Andre, he confesses his relief that it was his friend who should almost steal his wife’s heart rather than anyone lower down, or else he may have suffered an even greater humiliation.

“I’m glad it’s with someone from our set.”

There is another more comedic purpose served by Renoir’s rich depth of field too though, underscoring the dramatic irony of his characters’ limited perspectives. As Schumacher furiously plots his victory over his wife’s new suitor, Lisette quietly beckons at a hidden Marceau to sneak out of the room. He tiptoes behind an oblivious Schumacher, nervously jumping at his indirect threats, though his stealthy efforts are for nothing when he inadvertently sends a bench of crockery crashing to the ground. Just as Renoir refuses to cut from his wide shot of the following chase weaving in and out of rooms, neither does he shift his frames of long hallways that diminish his characters into tiny figures, or the doorway which frames a frantic Robert pass by a trigger-happy Schumacher and amusingly fail to note the similarities in their circumstances.

“Corneille, put an end to this farce!”

“Which one, your lordship?”

Interactions such as these are played at a cool distance, letting us join fellow guests who observe the manic drama with bemusement, though it is also a rare occasion that the camera is so static. The most dominant stylistic feature of The Rules of the Game, Renoir’s artistic innovations, and poetic realism as an entire film movement is that fluid camerawork floating around sets in long takes, sensitively soaking in the intricacies of their environments. In Renoir’s case, it is through this device that we appreciate the absurd wealth on display, as we traverse lavish halls of chandeliers, statues, and mirrors, and push through frame obstructions of drapes and flowers.

Renoir’s floating camera does not simply immerse us in these characters’ opulent theatrics though, but there is also enormous economy in its navigation of their dynamics, connecting multiple narrative threads as it detaches from one conversation and joins another. As the servants sit down for dinner in one scene, he coordinates an incredible tracking shot that constantly shifts between Schumacher, Lisette, Marceau, and the grumbling chef, each of whom enter and exit at different points while cooks move through the background. When scenes expand to fit almost the entire cast within them, Renoir’s long takes emphasise how little distance there is between both ends of the social spectrum. Petty grievances drive men to violently lash out, and women form phoney alliances with their enemies, stifling any genuine affection among friends or lovers with narcissistic compulsions to protect their own egos. The camera’s pace may accelerate with their movements, especially during tracking Schumacher’s armed rampage throughout the manor, but Renoir’s perfect, controlled elegance never wavers.

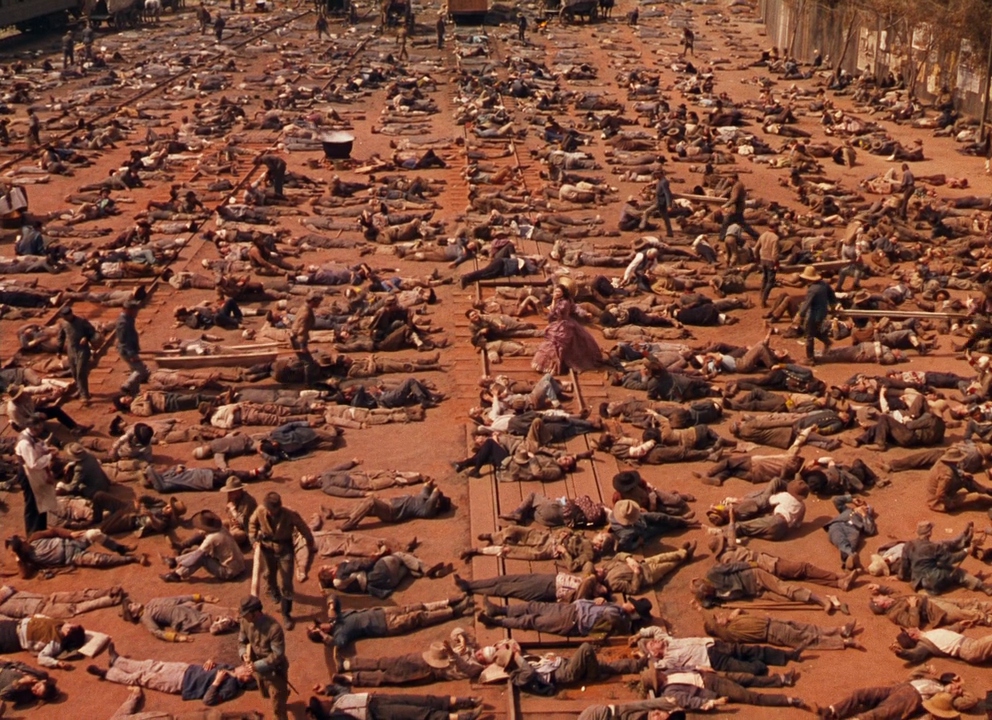

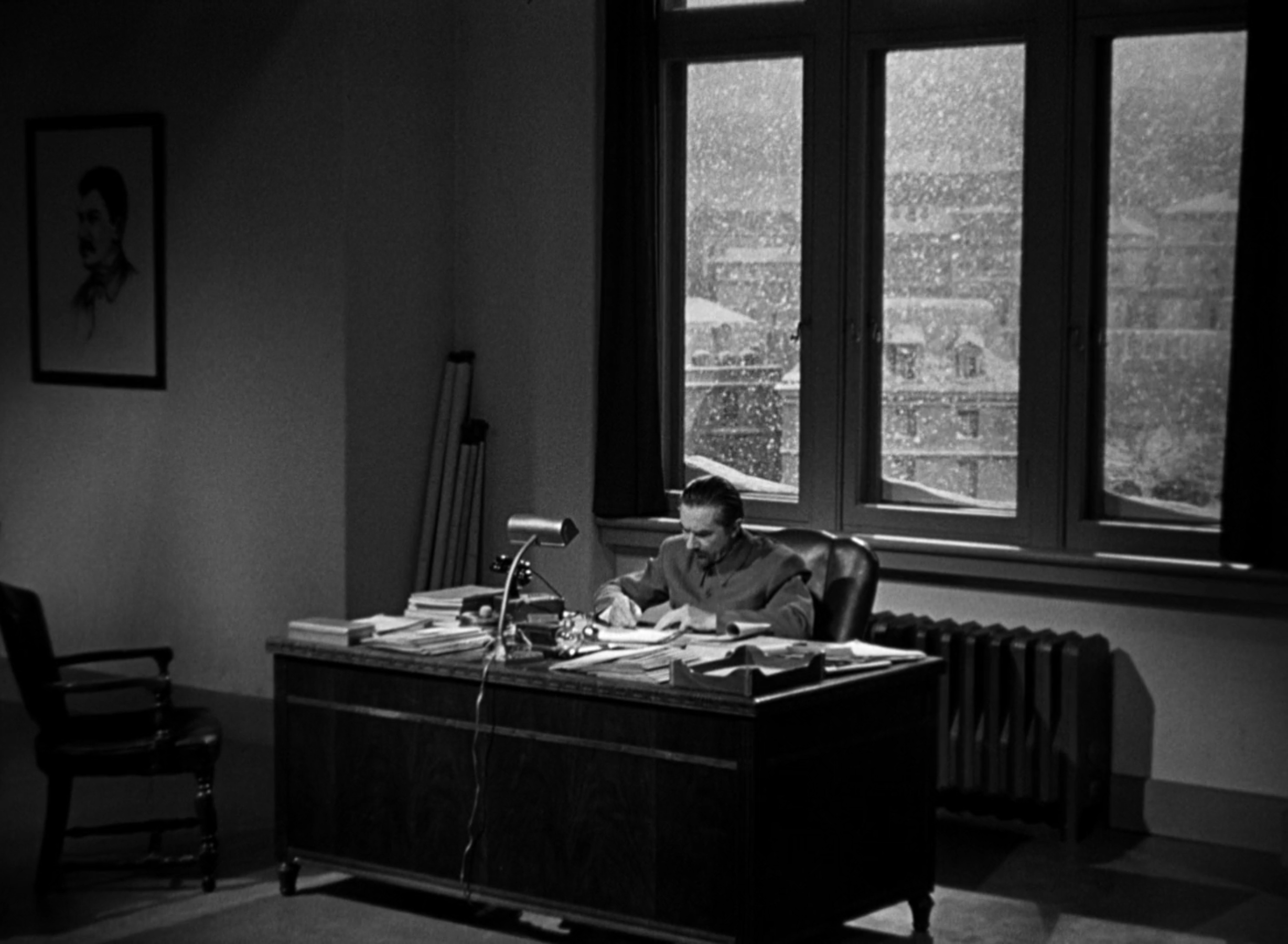

At least, that is the case within the boundaries of these sumptuous interiors, encasing them in worlds of superficial affluence. As guests and servants venture outside one fine morning to hunt wild game, Renoir exposes a more insidious evil that quietly resides within the bourgeoisie, and formally disrupts the fluid camerawork that pervades the rest of the film. Within the dense forest of thin, white trees that sits on the edge of Robert’s estate, we find a paradise of woodland creatures, exuding a far greater peace than the forced niceties of La Colinière. The camera nervously floats close to the ground as Schumacher and his men advance through this territory, banging their sticks and blowing their horns to draw out their prey, while Robert and company disperse themselves around the edge of the forest, rifles at the ready.

Suddenly, a cacophony of gunshots erupts, and Renoir launches into a truly aggressive display of montage editing – pheasants fall from the sky, rabbits collapse mid-run, and hunters coldly shift their aim from one target to the next, taking perverse pride in their domination of the animal kingdom. Afterwards as they collect the carcasses, a pair of them even argue over the etiquette of the sport, imposing the arbitrary rules of high society on the natural world and consequently laying claim to that too. Renoir may shatter the illusion of bourgeoisie sophistication to the viewer, yet still these aristocrats continue living in denial of their own repressed, violent impulses. It is no great ordeal living with a bit of blood on one’s hands after all when such sacrifices to class pride are framed as necessary traditions.

Renoir’s foreshadowing is thus laid out for the crushing tragedy that punctuates the final minutes of his film. He orchestrates here a masterful tonal shift here, preceding it with a farcical series of misunderstandings and mistaken identities that throw us off far off the scent of the imminent murder. The first sees Schumacher spy on Christine wearing her maid’s cape, confusing her for Lisette as she walks with the newest man to catch her eye – Andre’s relatively poor friend, Octave. The second sees Schumacher pursue a man he believes is Octave, yet is actually Andre wearing his friend’s cape. Driven mad with jealousy, and fully investing in a self-fabricated lie, Schumacher takes aim at the man he believes is Octave and shoots.

In effect, Andre is punished for the wrong crime by the wrong man who picked the wrong target, yet there is a fatalistic irony in the fact that he, much like Octave, is absolutely guilty of fooling around with Christine. Not even Schumacher had considered that separate classes might have romantically intermingled, seeing an upstairs woman fall into the arms of a downstairs man, yet it is this transgression of the rules which inadvertently leads to such tragedy. No one is quite sure how to make sense of this disaster, nor do they want to, should their illusions of order and security reveal weak foundations.

“He dropped like an animal in the hunt,” Marceau later recounts, and when Andre’s death is covered up as a hunting accident, the young aviator indeed becomes just another sacrifice to the status quo. There is no great fuss cleaning up the incidental bloodshed. Everyone is simply relieved that it wasn’t them who had the misfortune of wearing Octave’s cape, but the irony here does not escape Renoir’s pointed social satire. Today it was Andre, and tomorrow the unpredictable whims of their own volatile egos could put them on the wrong end of another reckless fool’s rifle. As long as this tacit danger continues to preserve their status and wealth though, then these self-centred aristocrats are content living with a constant mistrust of their own friends and lovers, and continue giving credit to the arbitrary rules of their empty game.

The Rules of the Game is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.