Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 27min

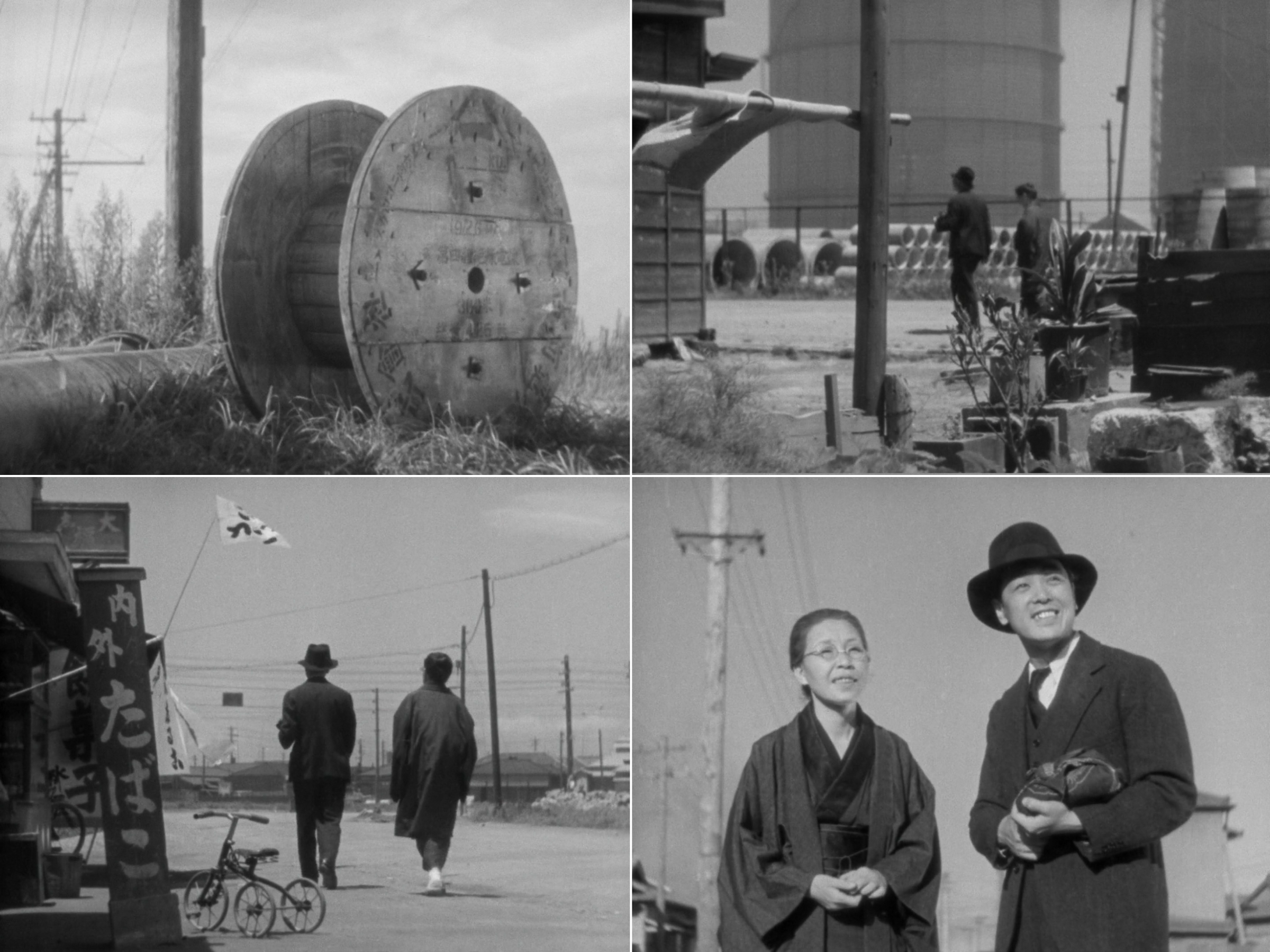

The Tokyo that Ryōsuke inhabits is not quite the bustling metropolis that his mother O-Tsune envisioned. His neighbourhood is a desolate wasteland of processing plants and garbage incinerators, raising chimneys high up above landscapes and imposing its industrial architecture upon locals. In fact, it isn’t terribly different from his rural hometown Shinshū, where O-Tsune worked hard for many years to send him to school and where she still toils away in her old age. Yasujirō Ozu regards the prospect of elevating one’s status through education with great cynicism in The Only Son, and given that the Great Depression was ravaging Japan’s working class at the time, it isn’t hard to see why.

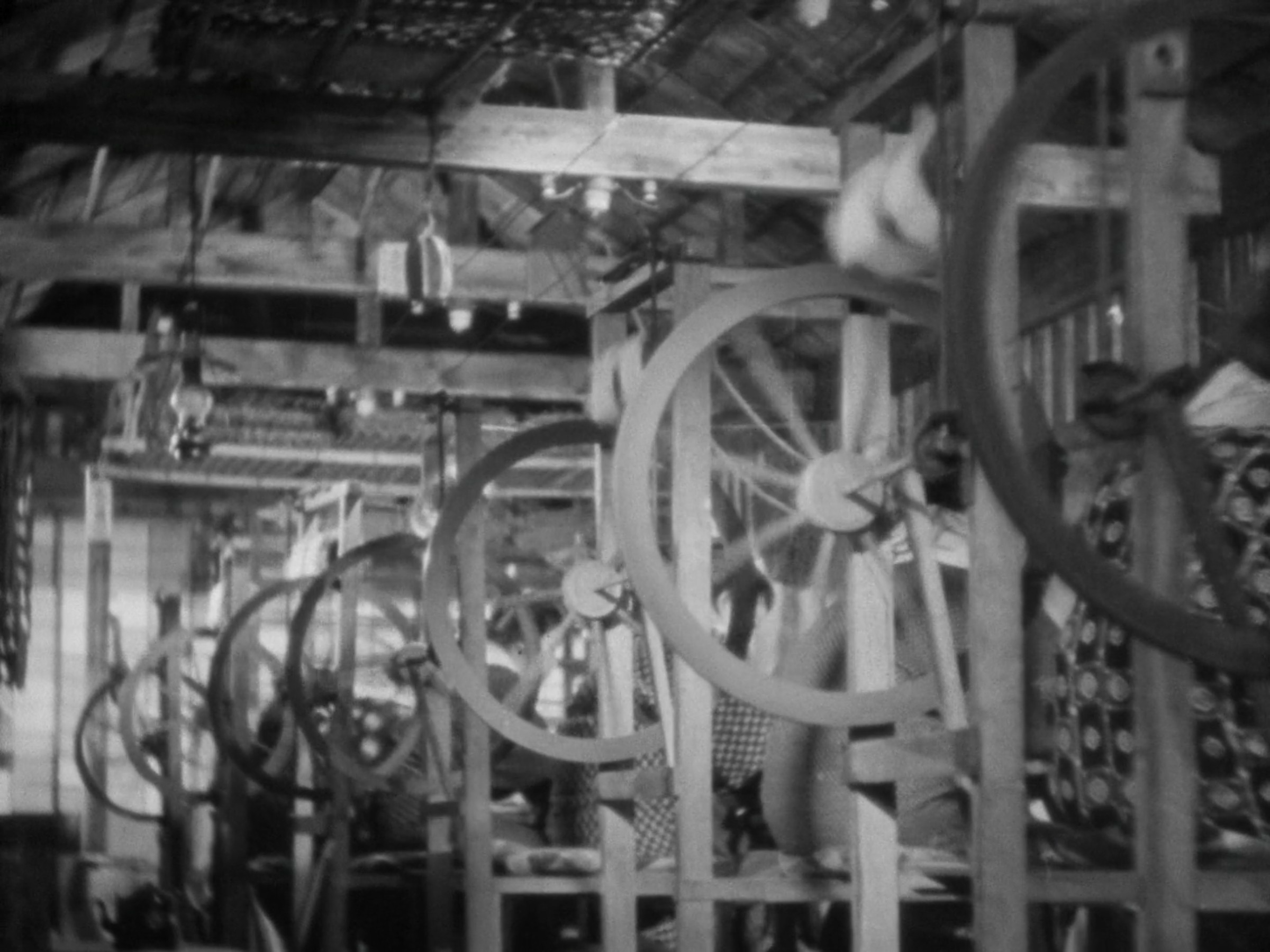

This is not to say that the destitute poverty Ozu’s characters live in lacks his typical aestheticism. His trademark pillow shots introduce us to Shinshū by way of oil lamps hanging in front of street views, and when we arrive at O-Tsune’s silk production factory, rows of spinning wheels whirl in smooth, geometric harmony. Humility begets selflessness in this quiet town, constantly grinding away to build a future for the younger generation in the naive hope that they will be granted greater privileges. After displaying immense talent in crafting the meditative melodrama of A Story of Floating Weeds, this tale of parental expectations and disappointments confirms Ozu cinematic genius, underscoring the social realities of 1930s Japan through the muted, disillusioning tension between generations.

Adding to O-Tsune’s weight of responsibility as well is her single motherhood, having been widowed shortly after Ryōsuke’s birth. Sending him to school placed a huge financial burden on her, yet thanks to advice from his elementary school teacher Ōkubo, it also seemed to guarantee him a comfortable life. When she finally visits him in Tokyo as an adult then, not only is she shocked to find that he has taken up work as a lowly night school teacher to support a wife and child, but that the once-respected Ōkubo has similarly taken a step down the social ladder and become a restaurant owner.

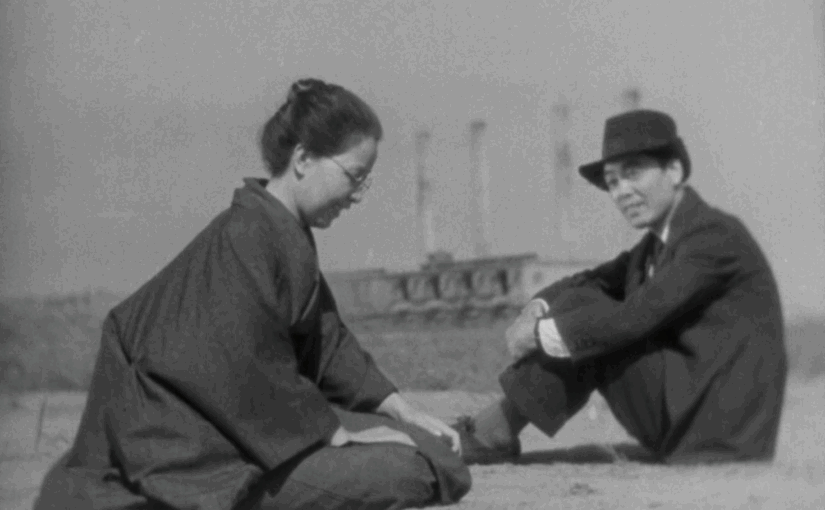

As O-Tsune and Ryōsuke sit and talk in view of Tokyo’s towering smokestacks, he is the first to admit that this was not the life he was expecting for himself. The city is simply too competitive, and he feels terrible for all his mother’s sacrifices, yet she initially remains hopeful. His life is only beginning after all, and she claims her only disappointment is in his readiness to give up – though later that evening, it becomes apparent that her regret is far more deep-seated. As Ryōsuke stands wistfully at the window of his classroom, gazing at the blinking city lights, Ozu’s mellow editing interlaces the scene with O-Tsune’s reflective, downcast expression back home. A narrow doorway confines both of them to a narrow frame as they finally meet and continue their discussion, though this time they are unable to reach as convenient a resolution.

“I worked hard because I wanted you to succeed,” O-Tsune laments, before finally coming clean that she has sold their house and mulberry fields for his education. “You’re all I have now in the world.” Ozu’s characteristic low placement of his camera proves particularly powerful here, levelling with them as their resilient facades drop for the first time to bare their bitterness and guilt. From the next room over, Ryōsuke’s wife Sugiko weeps, before O-Tsune and Ryōsuke join in. From there, Ozu sits in the lingering melancholy as it spreads through the house, cutting to their sleeping baby and an empty room. Within the stasis, Ozu imbues remnants of their sorrow, echoing pained, muffled cries while the unconscious child remains innocently unaware.

In moments such as these, the precision of Ozu’s pacing and composition become piercingly clear, as his montage seamlessly transitions to the next morning through shots of folded and hanging laundry. His characters may be wounded, yet life goes on, leaving them to pick up the pieces and keep showing the sort of love they themselves need in return. There is no long-lasting resentment on Sugiko’s behalf, as she sells her kimono to take them all out while the weather is nice, and Ryōsuke is proves his altruism as well when he instead uses this money to generously pay for his neighbour’s hospital bills. Plenty may change with the passing generations, yet the benevolence which is passed from elders to children paves the way for a redemptive union of the two. Perhaps it is good her son never became rich, O-Tsune resolves, lest he should have lost that graciousness she raised him with.

With Ryōsuke finally deciding to take one more shot at getting a licence to teach high school, it seems that O-Tsune is able to return home to Shinshū with some closure, though Ozu is not one to let his family drama subside so neatly. The enormous smile she wears back at the factory is bolstered by the pride she openly expresses in her son, and convincingly hides the sadness which emerges when she is alone. As she rests for a moment on a ledge, her forehead creases with weary dejection, revealing the impermeable regret which cannot be quelled in her old age. This factory has been her entire life, and as Ozu’s conclusive pillow shots move towards its giant, steel gate keeping her in, it is apparent that it always will be. And for what, we are left to wonder? Is one life lived in poverty worth another that is only slightly better off? Like an ellipsis at the end of a sentence, The Only Son’s final montage suspends its characters in an unshakeable discontent, striving for a prosperous, hopeful future they quietly recognise may never arrive.

The Only Son is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.