Victor Sjöström | 1hr 35min

Impoverished ingénue Letty is absolutely convinced that the Texan wasteland where she tries to plant her roots in The Wind is haunted, though not by any malevolent poltergeist or demon. High up in the sky, she envisions a ghostly white horse galloping among the clouds, stirring a gale which tears at the foundations of ranches down below. This invisible force of elemental chaos possesses no alliance to any greater good or evil, but exists of its natural accord. It is to be marvelled at, feared, and for those who are particularly susceptible to its maddening influence, hopelessly succumbed to in total resignation.

It is through this eerie visual motif that what would otherwise be a straightforward melodrama takes on dark psychological dimensions in The Wind, delivering a metaphor of profound, existential instability. Especially for a woman like Letty whose life is so consumed by turmoil, this restless tempest is a constant companion, blowing around debris just as she herself is helplessly tossed between homes and men. What she initially hopes will be a chance for a new life in Sweetwater offers little in the way of security, especially when she begins to realise how vulnerable she is at the hands of the local bachelors – not all of whom have honourable intentions.

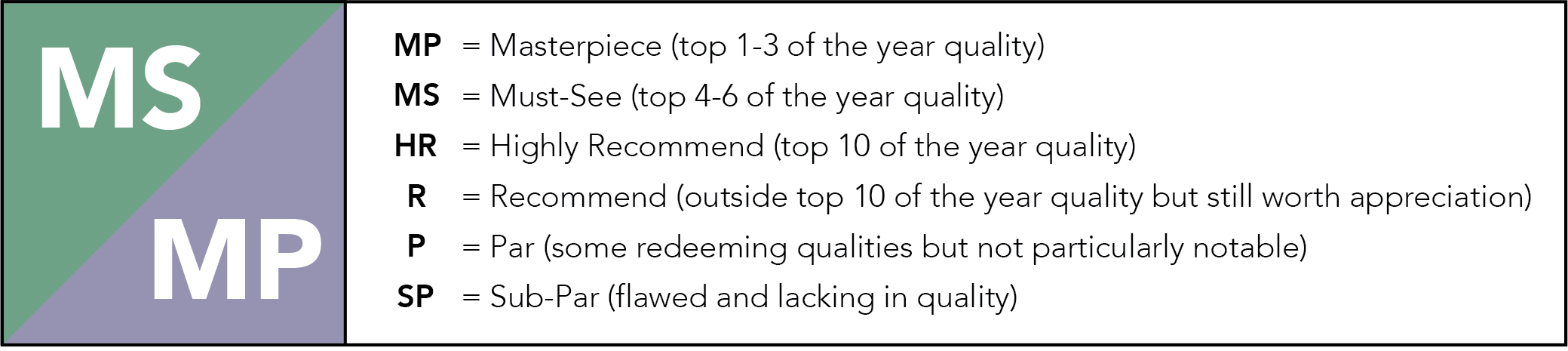

It is an uncertain, ever-changing world that she inhabits, and as an early pioneer of location shooting, Victor Sjöström is powerfully in tune with capturing its raw elements. California’s Mojave Desert effectively stands in for the Texan wilderness, and airplane propellors are cleverly situated just out of shot to simulate the titular winds, buffeting the actors’ hair and clothes. When an advancing cyclone turns a carefree party into an accelerating stampede to safety, even his blocking adopts that perpetual, unidirectional momentum. Standing amid the rush, Letty fearfully clings to her most persistent suitor Wirt, before being whisked away into an underground bunker with the other patrons. Clearly if she is to find any sort of stability, then she must hitch herself to a man, regardless of whether she finds the available options particularly appealing.

As D.W. Griffith’s muse, Lillian Gish was certainly no stranger to playing naïve, innocent women, though Sjöström makes even better use of her talents here to corrupt Hollywood’s paragon of virtue. Even when she is safe inside, her troubled gaze is constantly drawn to windows where views of the heavy gale slowly erode her sanity, and bitterness makes a home in her heart as she perseveres through a reluctant marriage to Sweetwater local Lige Hightower. Her adamant fury when he forces a kiss is strengthened by its contrast to her usually passive demeanour, and opens the door to a deeper mistrust of those men she once believed were meant to be protectors of women.

Wirt’s willingness to pursue her even after she marries Lige sets him apart as the worst of the bunch. She has already rejected him upon learning that he simply wants to make her his mistress, yet still he continues his advances, driving Letty mad with panicked terror. When he is brought to her place to recover from an injury one day, she can’t help but picture his leering eyes and creepy smile as he sleeps, rendered disconcertingly in a double exposure effect. With men like this hanging around, little can soothe her anxiety, which Sjöström soon builds to a fever pitch as the fabled North Wind plagues her home with howling, frenzied chaos.

Gish too seems possessed by this invisible force, her eyes stretching wide with terror and drooping into a hypnotic trance as she rhythmically sways with the hanging lanterns and camera. Kitchen bowls rock on shelves as if enchanted by spirits, and soon even the glass windows give in to the piercing wind, knocking over an oil lamp and setting a blanket on fire. In the sky above, that great white horse continues to whip up violent flurries, but a pounding at the door heralds an even greater peril – an opportunistic Wirt, taking advantage of Letty’s vulnerability to force himself on her.

The relative serenity of the following morning does not bring an end to Gish’s madness. She is deeply traumatised, and as she sits stiffly in a kitchen chair, the camera’s forward tracking shot directs our gaze towards the object of her attention – a pistol, lying atop a pile of debris. She seems prepared to defend herself, though later when she finally fires it into Wirt’s stomach, she can barely comprehend her own actions. Even after burying him, all she can do is watch in terror as the wind gradually re-exposes his body, convincing her that the pair of hands forcing open the front door belong to his vengeful spirit.

That it is Lige who enters cabin instead comes as a great relief to Letty, though even more reassuring are his words of comfort. “Wind’s mighty odd – if you kill a man in justice – it allers covers him up!” he proclaims, pointing out the weather’s mysterious concealment of her murder. Contrary to the rest of Sweetwater’s foreboding mythologising, this is the first suggestion that there might be some semblance of moral order in an otherwise lawless cosmos. Even more importantly, it is also the first demonstration of Lige’s selfless, forgiving love. With a steadfast certainty like this, all other doubts and insecurities fall away, and not even the winds hold the same psychological influence anymore as Letty and Lige bask in the draught of the open doorway. Worldly elements may ravage material constructs in The Wind, yet there is still peace to be found in Sjöström’s allegory of life’s erratic movements, delicately revealed in our ability to face its ravaging, mercurial turbulence.

The Wind is not currently streaming in Australia.