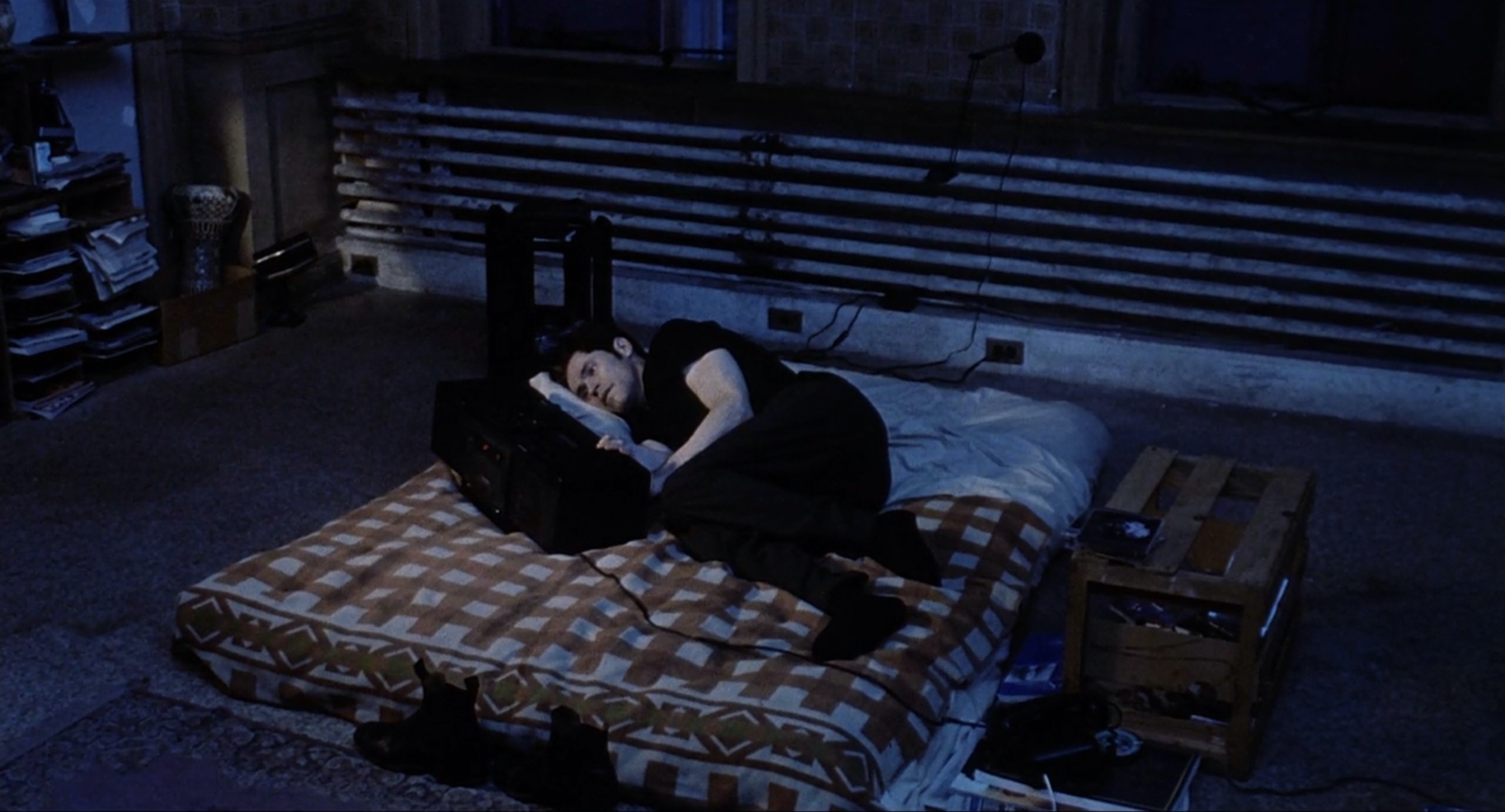

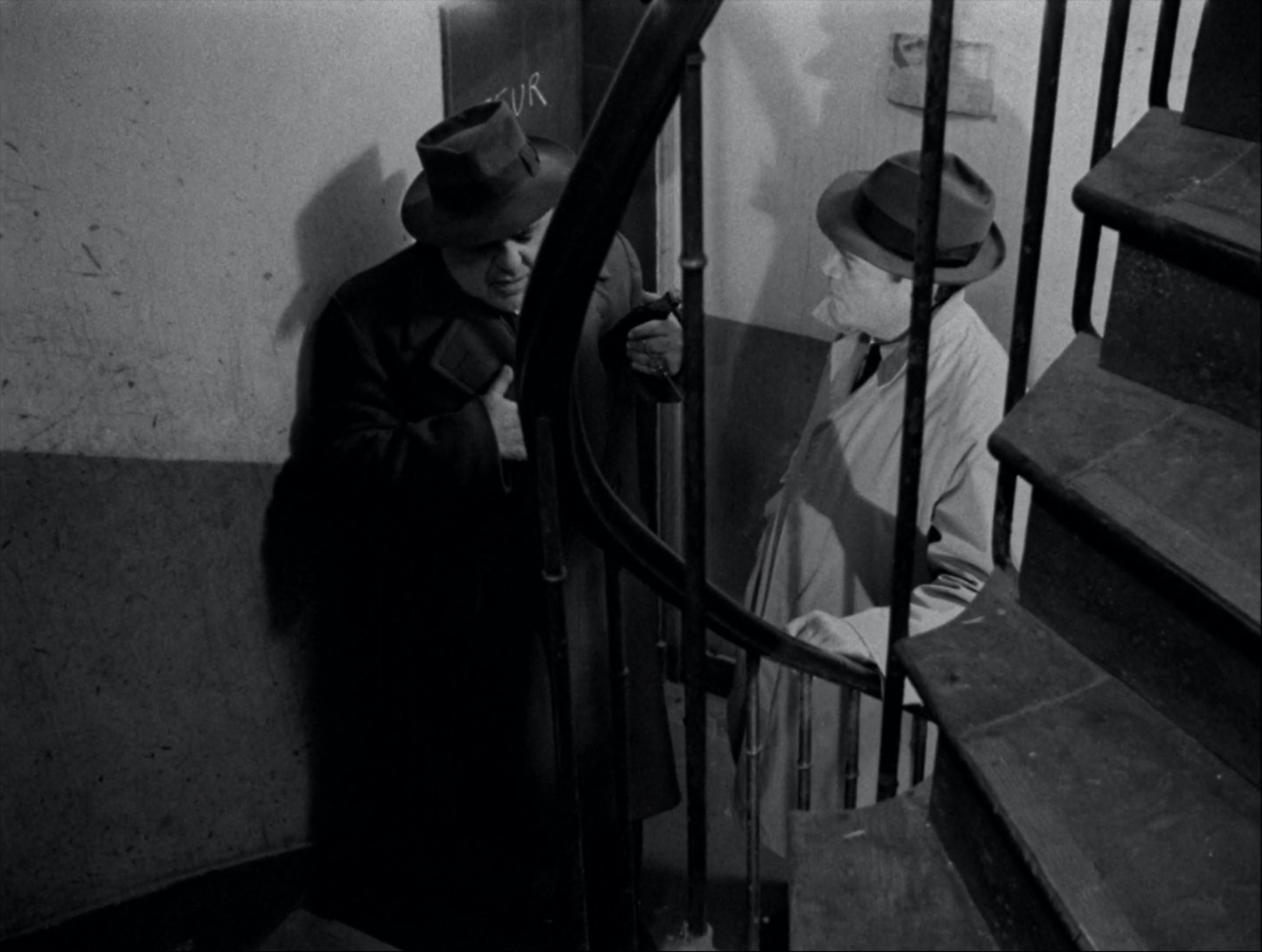

Eastern Promises (2007)

Even as David Cronenberg drifts away from explicit body horror and towards suspenseful crime drama in Eastern Promises, his camera never wavers from bloody acts of carnal violence, nor does it falter in its study of those symbolic tattoos which mark the skin of gangsters with their personal histories, mutilating their identities to fit the cultural traditions of a shady, soulless underworld.