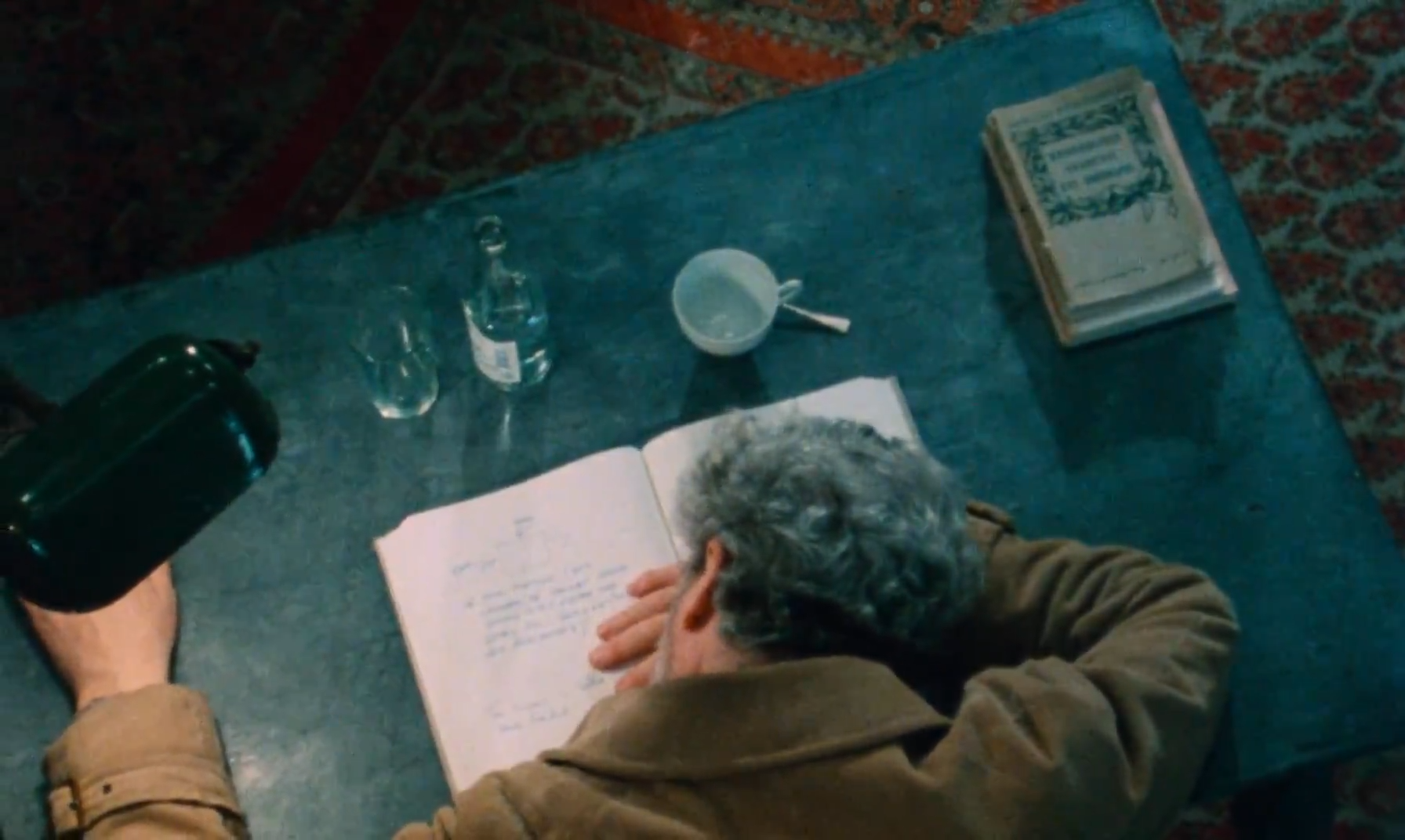

The Rules of the Game (1939)

The self-centred bourgeoisie of The Rules of the Game are content living with a constant mistrust of their own peers if it means preserving their status and wealth, becoming the targets of Jean Renoir’s biting social satire as he comically undercuts the egos entangling themselves in an intricate web of affairs over one weekend at a country estate.