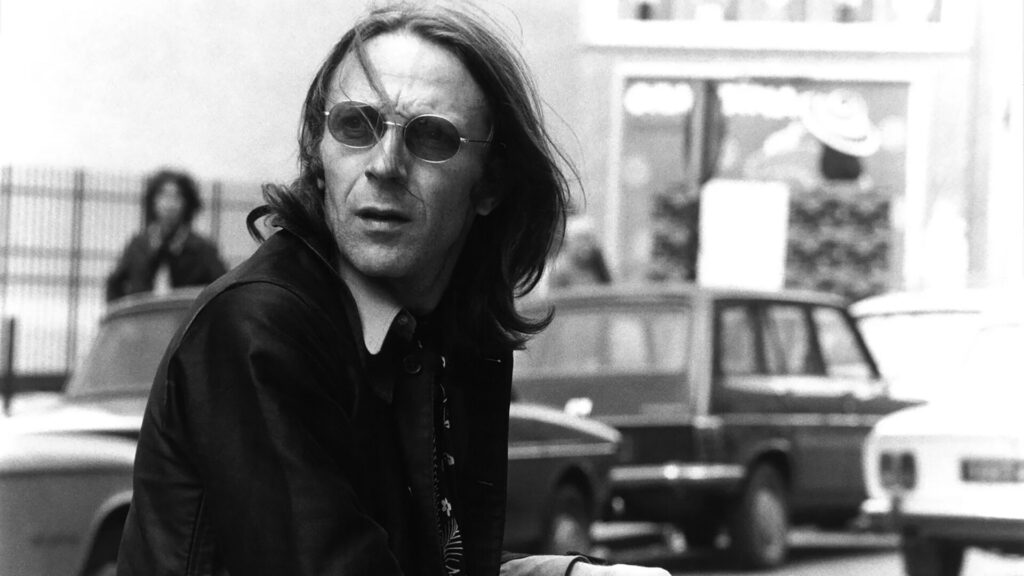

Strike (1925)

Much like factory workers uniting in organised rebellion against their exploitative managers, Sergei Eisenstein lets revolutionary formal purpose drive every editing choice in Strike, building symphonic set pieces out of montages that possess a brisk, mathematical precision.