Brady Corbet | 3hr 35min

When Hungarian-Jewish immigrant László Tóth first arrives in the United States, it is as if we are watching a birth from inside the belly of the steamship itself. The dissonant score of plucked strings and hollow percussion blend with the chaotic din of passengers below deck, scrambling in the darkness to catch sight of their new home. The handheld camera moves in a single, disorienting take with László through the crowd, submerged in total confusion, until finally a glimpse of blinding light pierces through. It takes a few seconds for our eyes to adjust when he exits, but as we gaze up at his beaming smile, we follow his line of sight to New York’s beacon of hope. The Statue of Liberty looms proudly over the tumbling camera, and as Daniel Blumberg’s booming, four-note theme breaks through the raucous sound design with orchestral grandeur, an awe-inspiring vision of the American Dream is announced – albeit one which has been turned totally upside down.

Upon moving to Philadelphia to work for his cousin’s furniture business, still that brassy motif continues to follow László through The Brutalist, welcoming him to a land of freedom and opportunity. There, his expertise as an architect comes in handy when he is hired to renovate a wealthy industrialist’s study into a library. After Mr. Van Buren gets over his initial confusion and outrage, it is also that incredible talent which lands László in the businessman’s inner circle, where he uses his careful craftsmanship to carve a path to prosperity. Still, at no point during their affiliation does László forget that this entire arrangement is founded upon unspoken caveats. As we traverse Brady Corbet’s epic immigrant saga, László’s relationships to both the United States and his homeland are knotted together, yielding complex artistic fusions from bitter nostalgia, soured dreams, and deep-seated cultural trauma.

The void which The Brutalist fills within modern cinema is one that is only ever occupied these days by films with equal parts mass appeal, artistic ambition, and vintage nostalgia. Right from the moment the word ‘Overture’ appears on a black screen in the opening seconds, it is clear that this is a throwback to the event films of a long-gone era, complete with a lengthy run time and a much-needed intermission. Even Corbet’s decision to shoot on VistaVision, a high-resolution format that fell from popularity in the 1960s, captures that fine, grainy texture and rich colouring of Golden Age Hollywood. With a score that also merges the classical majesty of Maurice Jarre and the avant-garde stylings of Jonny Greenwood, The Brutalist thoughtfully captures László’s split mindset in this country of contradictions, positioning him as an artist caught between the Old World and the New.

Of course, that music comparison inevitably draws us to the Paul Thomas Anderson parallels. From The Master’s introspective character study, Corbet borrows a wandering, post-war existentialism, haunted by substance abuse, sexual affairs, and memories of immense suffering. László Tóth is a far more sophisticated man than Freddie Quell, yet both seek some return to normalcy after being separated from their homes and loved ones. On a visual and narrative level though, The Brutalist bears greater resemblance to There Will Be Blood, building a grand mythos around the foundations and evolution of American capitalism. Like oil baron Daniel Plainview, László erects towering monuments of human progress from the raw materials of the earth, and Corbet’s astounding long shots bask in those rugged, monolithic structures rising from the green hills of Pennsylvania.

With that said, Plainview does not possess László’s eye for aesthetic and engineer’s mind, making his closest counterpart here the business-minded Mr. Van Buren. The entrepreneur’s bizarre description of their conversations as “intellectually stimulating” and the pedestal he places László upon at opulent dinner parties transcends mere admiration. In his eyes, this immigrant architect is an object of perverse fascination, fetishised for his exotic background, ingenuity, and trauma. Repressed homoerotic attraction and jealousy stoke feelings of insecurity in Van Buren, who finally encounters a barrier that money can’t overcome. As such, the closest he can get to possessing László’s intrinsic gift is through exploiting his labour. This largely comes in the guise of generous benefaction, though when all that charm is stripped away, Corbet reveals a hideous, hateful creature who takes advantage of his subordinate in far more depraved ways as well.

Van Buren easily stands among Guy Pearce’s most compelling characters, played with a roguish allure that draws the respect of similarly powerful allies, but it is Adrien Brody who comes out even stronger in his raw, battered performance as László. He is the culmination of countless devastating experiences, each resulting in unhealthy coping mechanisms that only deepen his psychological wounds. In particular, the heroin that was commonly used to treat pain on the journey to America becomes a toxic habit, frequently used as self-medication. When he attends a club early on to get high, the camera’s energetic swinging at low angles among musicians and dancers eventually gives way to a slow, lifeless zoom in on his glazed-over expression, while the upbeat jazz music nightmarishly dissolves into discordant mayhem.

When László is hard at work on the other hand, Brody projects a supreme, self-composed confidence that seems entirely compartmentalised from his drug-fuelled breakdowns. His genius is limitless under the right conditions, taking physical form in those imposing buildings and interiors which are celebrated in Corbet’s photography. The library especially is a feat of clean, minimalist design, creating a forced perspective from the entry towards a rounded window wall where sunlight filters through translucent white drapes. The bookshelf doors which open in graceful unison make for an elegant touch here too, though it isn’t until Van Buren commissions the architect to construct a community centre that his style evolves into full-fledged brutalism.

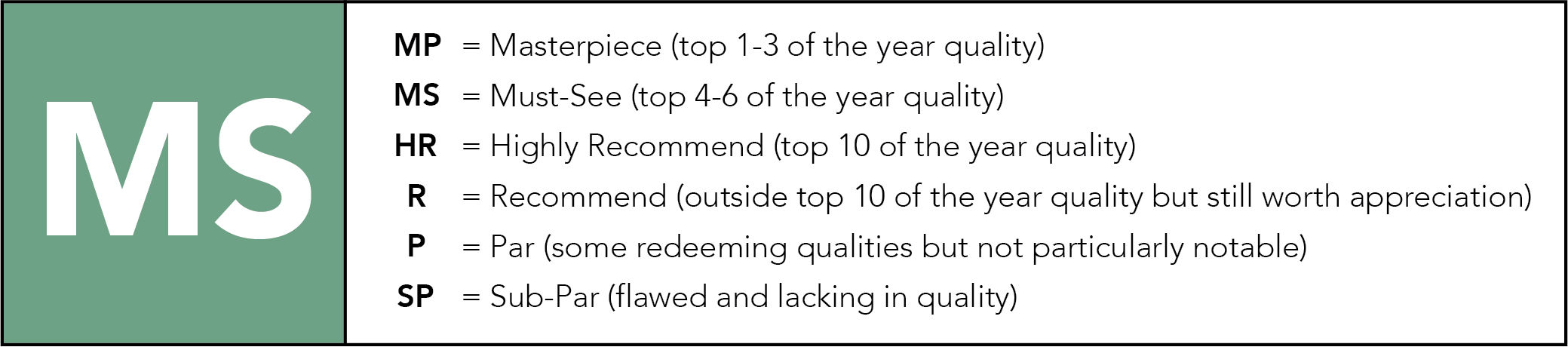

Concrete is a sturdy and cheap material, László reasons, though visually it also makes a powerful statement in its rejection of smooth, polished textures and ornamentations. From this coarse mixture of cement, water, and aggregates, his giant slabs and pillars impose a geometric simplicity upon the rolling countryside, while also expressing a creative, spiritual reverence in the cross that forms from the negative space between two towers. Timelapse photography and metric montages fuse with Blumberg’s driving score as progress is made in the construction, though even beyond László’s creations, Corbet’s camera continues to gaze in wonder at the steep terraces of Italian marble quarries and the vast, steel scaffolding of industrial sites.

After all, don’t those structures which service our basic needs for shelter, security, and community stand at the cornerstone of human civilisation? On a cultural level too, don’t their aesthetic and functionality define entire historical epochs, while also transcending time itself by nature of their permanence? With an immigrant at the centre of this story, Corbet is keenly aware of the irony here – not only was American modernism largely shaped by outsiders importing ideas from Eastern Europe, but those same innovators suffered greatly within the nation’s oppressive economic system.

Being divided cleanly into a rise and fall narrative structure, it is The Brutalist’s second act which especially traces that growing disillusionment, setting László on a steady downward slide. With the arrival of his wife Erzsébet and niece Zsófia as well, it becomes even more apparent just how emotionally stunted he is, keeping him from recovering the stable, loving relationship they shared before the war. Soon, both women join him in recognising the emptiness of America’s promises. “This whole country is rotten,” Erzsébet mournfully laments after his attempt to treat her pain with heroin goes disastrously wrong. At this point, it seems that the only way out is to begin a new chapter of their lives in Israel.

Unfortunately, it is also this latter half of the film which strays from Corbet’s tight, economical storytelling, stagnating in some plot threads while wandering down others that aren’t so cleanly integrated. As a result, the end of László’s arc comes about abruptly, with nothing but a tonally jarring epilogue to reflect on the legacy he left behind. The monologue here is overly expository, clunkily revealing layers to his artistry which link back to his experiences as a Holocaust survivor, and it is incredibly disappointing that our first proper viewing of the finished community centre comes through fuzzy video tape footage.

Instead, the most impactful conclusion to The Brutalist arrives at the end of Part 2. Corbet’s handheld camerawork and long takes have consistently imbued this epic with a primitive intimacy, and now as Erzsébet confronts Van Buren in front of his friends, both are used in a single, tremendous shot lasting several minutes. All at once, the polite civility which has long maintained the systemic injustice he has profited off crumbles, exposing a cowardly, insecure man who is nothing without the respect of his peers. Where László’s legacy is substantial and far-reaching, the haunting ambiguity of Van Buren’s own fate appropriately transforms him into a ghost of sorts, intangibly bound to that magnificent community centre and the talented architect who designed it. Such is the nature of a culture which purposefully imbalances the relationship between investor and creator though, and as this sprawling, historic fable so vividly expresses, it is often the latter who bears the true cost of progress.

The Brutalist is currently playing in theatres.

Have you seen Vox Lux (2018) ?

Not yet, but I’m intrigued. Have you?

I haven’t either. I think he has another film(his debut) with Robert Pattison called Childhood of a Leader in 2015. And was a very prominent Indie actor before that(now retired I think).

So this is a Must-See. Does that mean there are no masterpieces in 2024. The 2020s have been brutal.

There’s still a lot I have to see, and some grades could change before I put up my 2024 page – but this has been a pretty weak decade so far.

Amazing review as always, but I have to say that I do not agree with the idea that the Brutalist’s epilogue is meant to be clear cut exposition on what Laszlo wanted to do with his work, nor are we supposed to take what his niece says at face value about “it is the destination not the journey”, she’s clearly wrong and projecting her own opinion and the rest of the film reflects that. Laszlo says nothing in this epilogue, he’s not even 70 yet lost the use of his legs and his wife passed away relatively young from her illness and his “greatest work” bears the name of the man who abused,raped and discarded him. This idea that his niece imposes on his work, is in line with her character who is convinced that things will be better if they move to Israel, a positive destination that makes the horrors of the journey obsolete. But Laszlo understood that going to Israel wouldn’t just wash away the horrors he’s endured, having already faced rejection from his cousin and knows his wife to be looked down upon as “not truly Jewish”, and either way, no silver lining could ever be a destination that would make the holocaust as well as all he endured in America worth it. Laszlo’s greatest pain at being a “poor immigrant” was how he had lost his identity as a respected architect, wich fueled his obsession with completing the project, not seeing (or ignoring) how he was just seen as an exotic commodity of an artist. And in the end, he obtained a level of “prestige” being presented to the world as a immigrant architect who succeeded in America and healed from the holocaust through his work. But that is simply not true.

For me the film rates as a masterpiece, but I’d agree the 2020’s have been slooow so far. Just comparing 2020-2024 to 2010-2014 or 2000-2004 or any first 5 years of any decade before is rough.

You make a strong point, I think I would just need another watch to see how well that is set up. I do like the irony in how his achievement ultimately manifests.

Pingback: 2025 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2024 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green