Robert Eggers | 2hr 12min

Unlike the suave Count Dracula, there is nothing even slightly charming about the ghastly, cadaverous Count Orlok. He may have emerged as a legally dubious reimagining of the literary character in F.W. Murnau’s silent horror Nosferatu, yet he outwardly represents something far more grotesque than the seductive nobleman, bringing plague and decay to the German town of Wisborg. This is not to say that Orlok’s character is divorced from any notion of sexuality though – quite the opposite in fact, as this creature’s overtly carnal voraciousness is more heightened than ever in Robert Eggers’ handsomely chilling remake.

Gone are the murine teeth and wide-eyed gaze of Max Schreck’s ancient vampire, and in their place Bill Skarsgård delivers an acutely Slavic interpretation, sporting a heavy fur coat, bushy moustache, and deep, Eastern European accent. His commitment to this otherworldly voice by training in opera and Mongolian throat singing is astonishing, carrying the weight of character work while his face hides in shadow, and his naked physicality when latching onto victims is similarly unsettling as he pulses upon them like a pale, writhing leech.

Unlike most mainstream depictions of vampires, Eggers’ rendition of Orlok also feeds from the chest rather than the neck, remaining true to some of the oldest legends which depicted them as reanimated corpses that kill purely out of malice. It is not only a testament to the thorough research which informs Eggers’ mythologising, but such a viscerally intimate embrace also blurs the lines between intercourse and breastfeeding, underscoring the shameful, psychosexual desires which expose each character to Orlok’s disturbing pull.

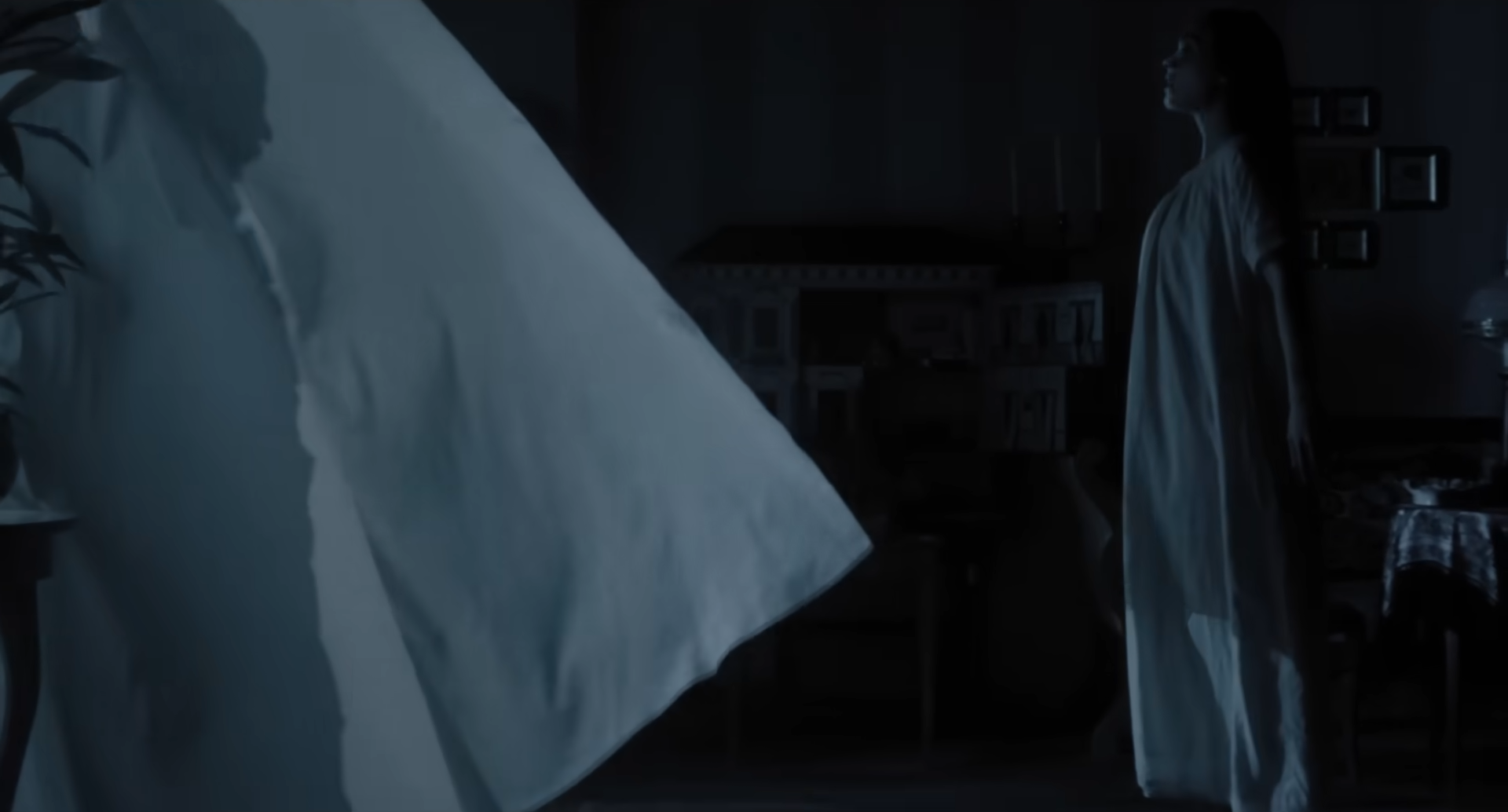

Easily the most vulnerable among these victims is Ellen Hutter, wife to real estate agent Thomas Hutter who has been tasked with securing Orlok’s purchase of a new home in Wisburg. Years ago, she made a deal with the creature which psychically bound them together, and now his influence reaches back into her life through nightmares, demonic seizures, and the orchestrations of his deranged servant, Herr Knock. There is a conflict within her that many others also suffer to some degree, whether in Thomas’ perverted arousal at her possession or her neighbour Friedrich’s depraved expression of grief through necrophilia, though she holds a unique position as the object of Orlok’s desire. He seeks to satiate his lustful obsession by entering her dreams, and while she reflects on their ethereal connection with a blissful smile, that instinctual happiness also terrifies her at the same time. Isabelle Adjani’s landmark performance in Possession bears a sizeable influence on Lily-Rose Depp’s acting here, ironically even more so than her portrayal of the equivalent role in Werner Herzog’s remake Nosferatu the Vampyre, and it is through these strong dramatic choices that Depp displays total command over Ellen’s deep-seated torment.

“He is my shame, he is my melancholy,” she confesses to Thomas, posing a metaphor that quite aptly describes this specific representation of the ancient vampire. Orlok is every disgraceful, buried secret now risen from the dead, eating away at those who guiltily try to repress them. With this in mind, Eggers’ design of the character as a ghoulish, Transylvanian nobleman who speaks the extinct Dacian language effectively connects him to a piece of long-forgotten Eastern European history, imbuing his image with a gritty, sinister authenticity. He is not some unfathomable figure beyond human comprehension – he is that part of ourselves which we hide away from the world, lest we should suffer the indignity of revealing our souls’ true corruption.

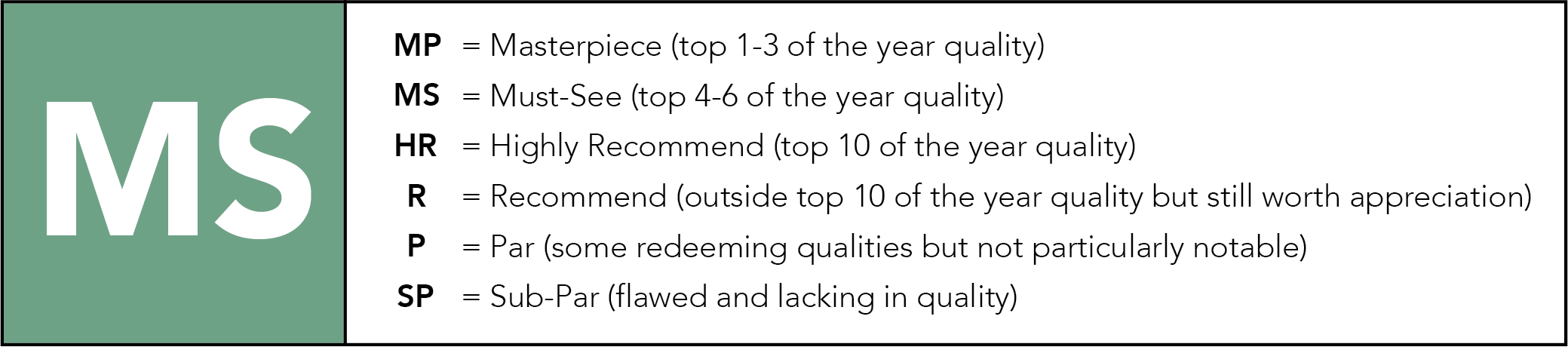

Nevertheless, these secrets cannot be hidden away forever, and the shadows they cast across Eggers’ meticulously curated sets are mighty indeed. The dark, distinctive outline of Orlok’s clawed hand wields a strange power as it reaches across bed chambers and castle corridors, often acting like a disembodied ghost detached from his physical being, and becoming a living extension of the film’s dour expressionism. Eggers’ visual style remains conscious of Murnau’s cinematic legacy here without becoming derivative, crafting imposing images from chiaroscuro lighting and eerily floating his camera with subdued dread, yet influences from silent cinema at large also leave their indelible imprint on his nightmarish designs. The driverless stagecoach which delivers Thomas to Orlok’s manor pays direct homage to Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage, while the presence of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is felt in the winding stairs, alleyways, and streets of Wisburg.

In fact, so uniform are Eggers’ colour schemes that many scenes almost appear totally monochrome, washing out landscapes in blue-grey tones beneath overcast skies and embracing fire-lit interiors that glow like hellish furnaces. It is according to these palettes that he also dedicates Nosferatu’s painstaking production design, extending his extensive folklore research into the architecture, costumes, and ornamental details of 19th century Germany, as well as Orlok’s 16th century Transylvanian castle. True to Eggers’ love of history, little is updated for contemporary audiences, and no shortcuts are taken in this devoted rendering of the past. It is rather in faithfully recreating every fan-tie corset and Gothic stone archway that he grounds the supernatural in our world, locating it close to the heart of humanity.

In Nosferatu’s screenplay as well, Eggers is not so much subverting horror conventions than executing them with poetic flair, achieving a 19th century stylisation in the dialogue which elegantly weaves macabre metaphors among other rhetoric devices. In fact, the only trace of modernisation on display may be in the freedom of its subtextual and explicit sexuality, edging us gradually closer to a full consummation of Ellen and Orlok’s sordid affair.

Unlike Dracula’s equivalent character of Mina Murray, Ellen is not depicted as the archetypal ‘pure virgin’ in Nosferatu, but rather a married, mature woman destined to play a far more active role in confronting the vampire. Additionally, this version of the famed vampire cannot be easily overcome by weapons or sheer force. Only by playing his game of seduction may he be reduced to his most vulnerable state, and so dressed in a bridal white gown and veil, Ellen chooses to make a fatal sacrifice.

If shame is a parasite which thrives in darkness, then light is anathema to its very being, exposing its feeble, pathetic decrepitude to the world. No longer does it stoke fear, but simply disgust at its pitiful existence. At the same time, accepting this monstrosity as an inextricable part of oneself may also bring death to its host, and it is here where Eggers reveals the tragedy which comes sorrowfully paired with the conquest of primitive, libidinal desire. Like all great fables, Nosferatu is straightforward in its clean divide between virtue and sin, order and chaos, life and death – yet it is through the blurred union of each in the guilty hearts of humans where this vampiric legend manifests its most familiar, archaic horror.

Nosferatu is currently streaming on Netflix and Binge, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

This is a great review, you really highlight the film’s strengths and pick out some of my favorite frames. Bill Skarsgård working with an opera singer to create that voice was well worth the effort. I love the original and Herzog versions so much, I was a little worried that my expectations might result in disappointment; they absolutely did not. I have seen it 3 times now including seeing it in theatres. Robert Eggers is a special talent

Great job with the site in general, I just started a Fritz Lang Study so I’ll check out the pages you have for his films

Pingback: 2025 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2024 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Editors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Cinematographers of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green