Jack Clayton | 1hr 40min

Flora and Miles may only be children, but by the time Miss Giddens meets them in the opening of The Innocents, they have already suffered more than most their age. Besides being orphaned as infants, their uncle and legal guardian prefers to keep an emotional distance, letting hired help carry the heavy load of parenting instead. The recent deaths of his valet Peter Quint and their previous governess Mary Jessel have no doubt also left them traumatised, and so it is little wonder why Miss Giddens is so concerned for their welfare when she is hired as the latter’s replacement.

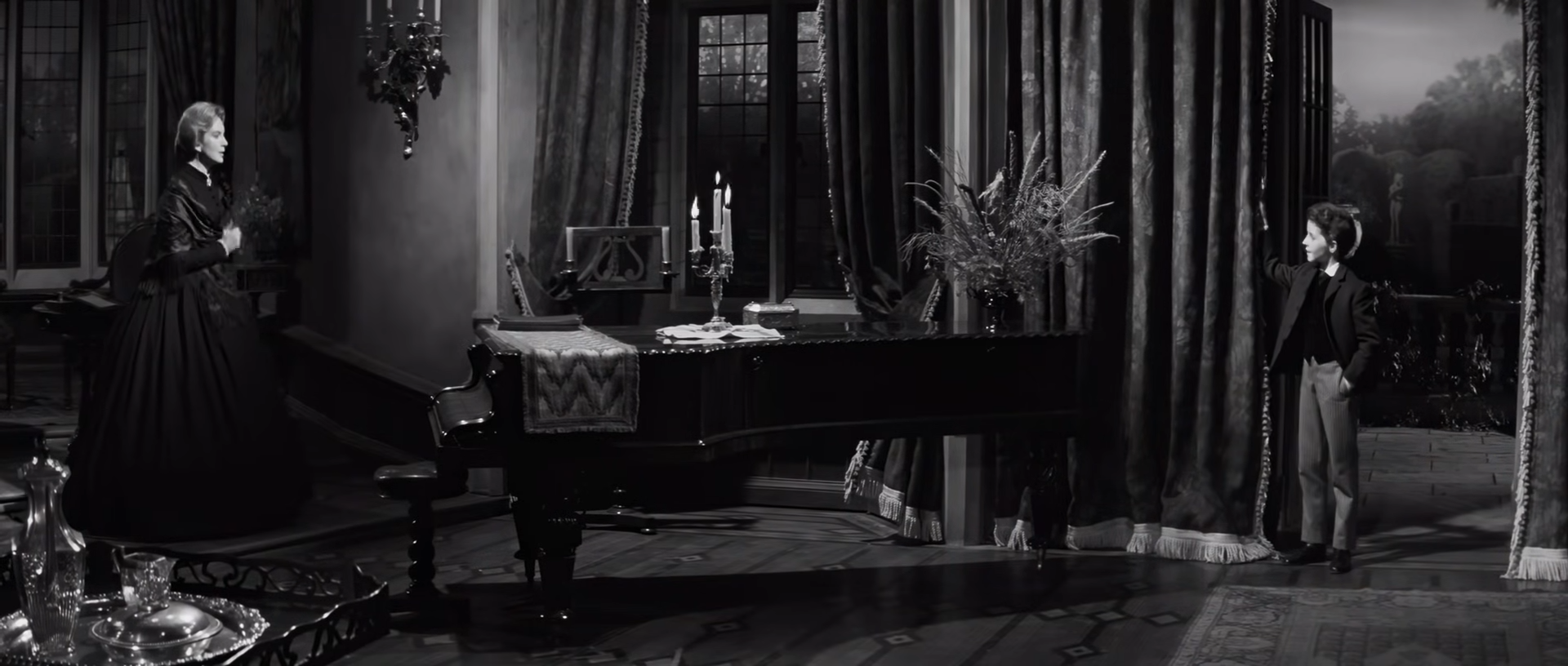

On top of all that, there seems to be another sinister influence taking hold of Bly Manor which is not so easy for her to pin down. The children’s behaviours are atypical, if not downright disturbed, especially with Flora being oddly drawn to the lake where Jessel supposedly drowned herself. Miles on the other hand acts strangely grownup for his age, unsettling Miss Giddens with inappropriately intimate gestures and hiding the dead body of one of his beloved pet pigeons beneath his pillow. Even more chilling though are the two ethereal figures flitting in and out of view, not only convincing Miss Giddens that Bly Manor is haunted by the spirits of Quint and Jessel, but that they are also possessing the children. These ghosts were lovers when they were alive, she learns from the housekeeper Mrs Grose, and now it seems that taking human vessels is the only way they can remain together.

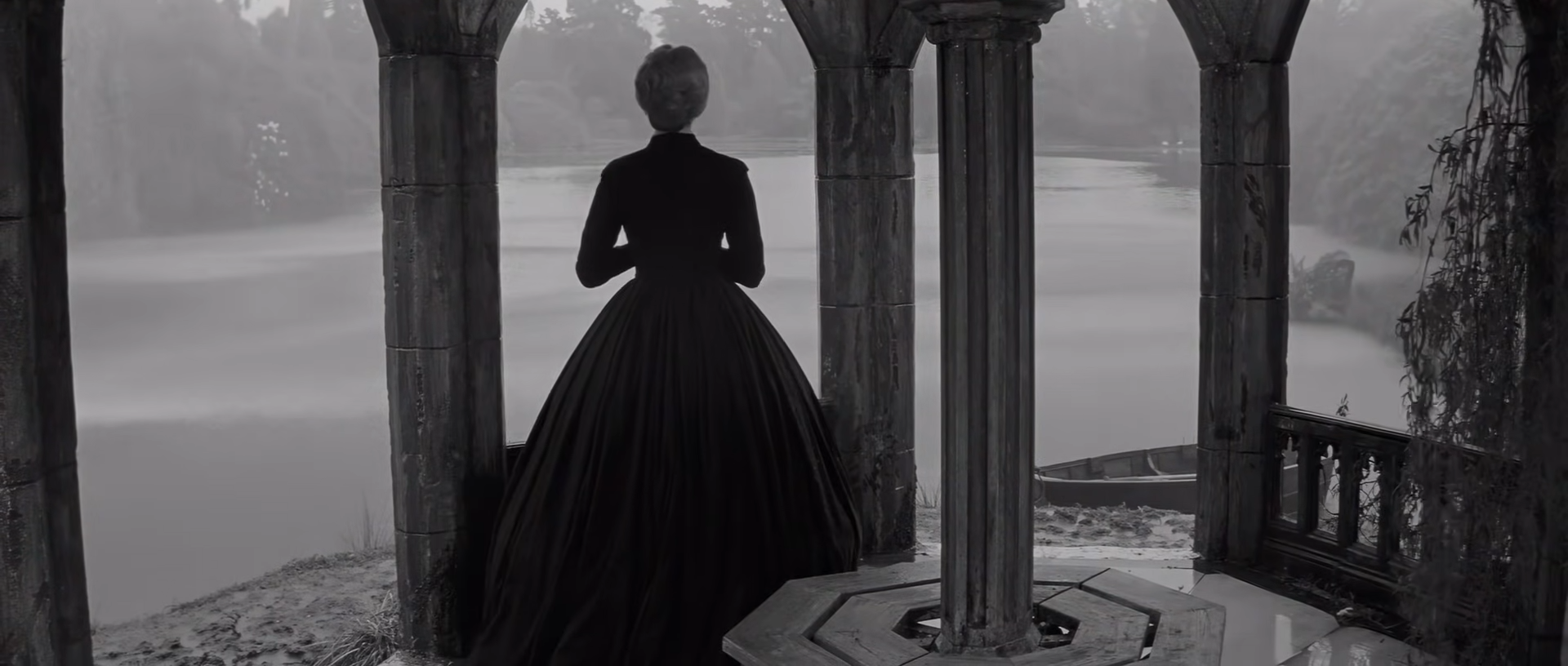

Still, the doubt which Jack Clayton infuses in this supernatural mystery is hard to shake, especially given that much of it surrounds Miss Giddens herself. Beyond Deborah Kerr’s nervous infatuation when she meets the children’s uncle in the opening scene, she also carries a general uneasiness around any hint of carnal desire, hinting at a sexual repression stemming from her own conservative youth. If she is to preserve Flora and Miles’ innocence, then she must first release them from the spirits which seek to corrupt it, exposing their true nature once and for all.

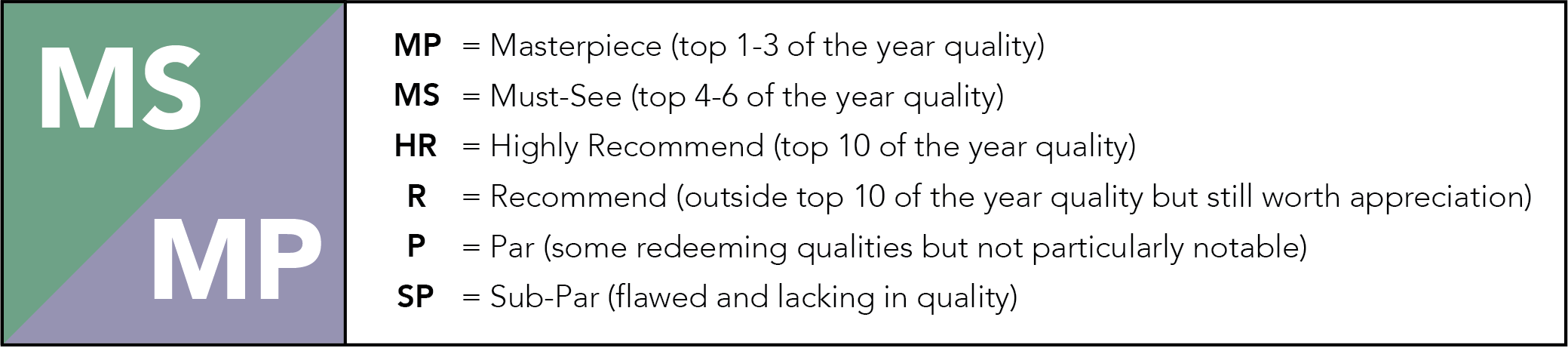

That Kerr also plays Miss Giddens with such warmth and sensitivity though only obscures our judgement of her weaknesses. She does not project the image of some deluded, Victorian relic, but rather a woman whose maternal instincts grant her empathetic insight into the lives of children and the dangers of their environment. From the moment she enters Bly Manor, she is at odds with its menacing atmosphere, blinded by the light in its picturesque gardens and absorbed into the darkness of its Gothic hallways. The sets that Clayton constructs here are remarkably detailed, filling out backgrounds with paintings, statues, and patterned wallpaper, and elsewhere framing characters within gaping archways.

Just as astounding though is also his rendering of this space through delicately subjective camerawork, quietly revealing its grim, ominous nature. Despite making excellent use of the CinemaScope format, Clayton’s cinematographer Freddie Francis chose to selectively hand-paint the edge of his lenses, slightly narrowing the wide frame and creating a claustrophobic vignette effect. The impact is understated but powerful, suggesting a pervasive darkness that closes in on Miss Giddens’ very presence. The clarity that Clayton offers us in his deep focus photography of two shots is also deceptive in its apparent objectivity, in one composition positioning her nervous expression behind Flora who curiously studies a spider devouring a butterfly. Alternately, her anxious expressions are frequently foregrounded in intimate close-ups, subtly warping her face through wide-angle lenses.

These are piercing images worthy of comparison to Orson Welles or William Wyler, and with Clayton’s surreal long dissolves, candle-lit interiors, and creeping camera movements in the mix as well, The Innocents effectively develops its own unsettling visual character. By the time Jessel and Quint fully reveal themselves to Miss Giddens, the psychological horror has already set in – though how much of this is merely the disintegration of a tortured mind remains agonisingly ambiguous. The governess is ready to save the children no matter the cost, and so after sending Flora to her uncle’s place in London with Mrs Grose, she is finally ready to directly address these ghostly disturbances with Miles one-on-one.

As the orphaned boy wanders through the greenhouse to the sound of trickling water and chirping crickets, Miss Giddens pursues him with an intensive line of questioning. “Sometimes I heard things,” he nervously confesses. “And when did you first see and hear of such things?” she pushes, only to be met with an unsatisfying reversal.

“Why, I made them up.”

Their faces grow clammy with sweat through this interrogation, and the glass panes of the greenhouse gradually fog up – though not enough to obscure the manifestation of Quint’s creepy, malicious grin pressing in from the outside. As if possessed by his wickedness, Miles launches into a brutally honest outburst, and drastically shifts away from his typically cool, sophisticated demeanour.

“You don’t fool me. I know why you keep on and on. It’s because you’re afraid, you’re afraid you might be mad. So you keep on and on. Trying to make me admit something that isn’t true. Trying to frighten me the way you frighten Flora. But I’m not Flora, I’m no baby. You think you can run to my uncle with a lot of lies. But he won’t believe you, not when I tell him what you are. A damned hussy! A damned dirty minded hag! You never fooled us. We always knew.”

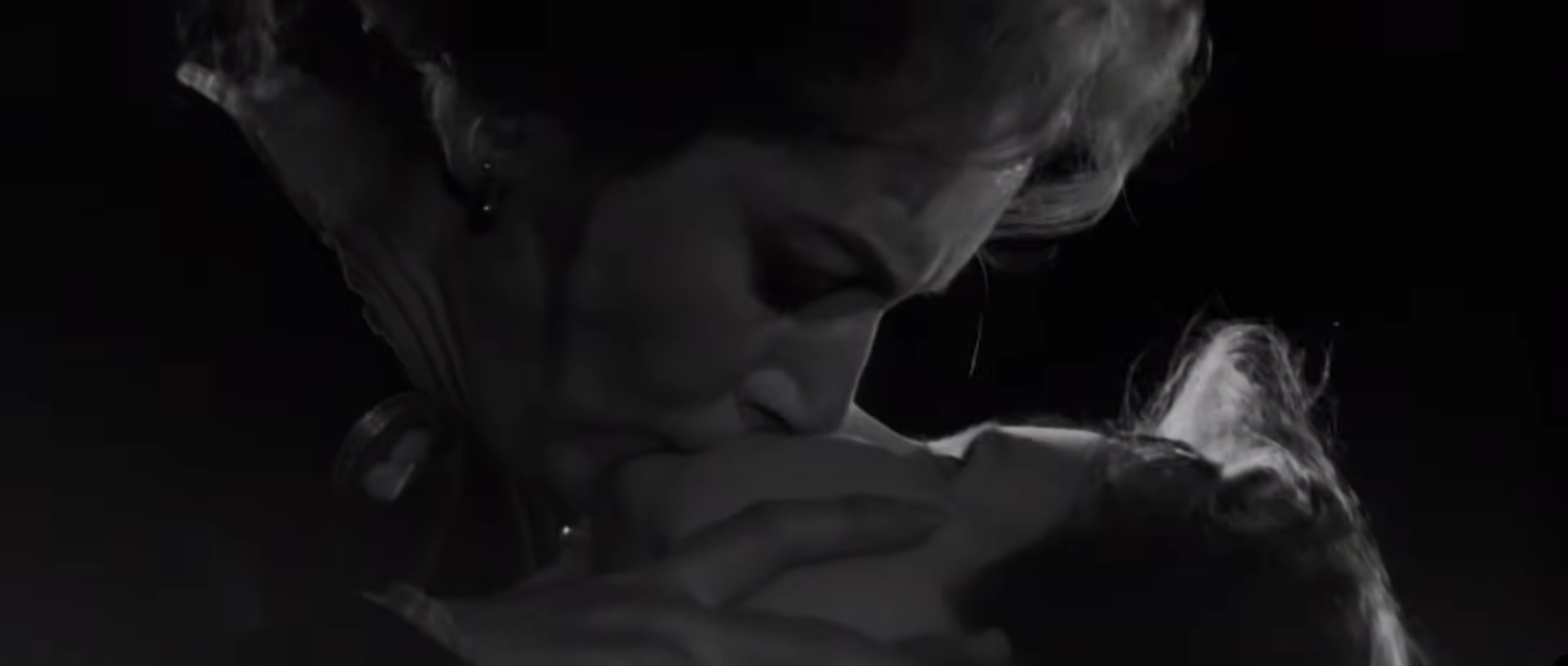

Miles and Quint maliciously cackle in unison at the terror on Miss Giddens’ face, and even after the young boy has seemingly managed to regain his senses, the malevolent spirit does not let go so easily. Gazing down from a high angle in the statue garden, Clayton’s camera suddenly adopts a new perspective for the first time in The Innocents – that of Quint himself, his hand raised in the foreground as if casting a spell over Miles. We might almost assume this to be confirmation of Miss Giddens’ supernatural suspicions were it not for Clayton’s reiteration of this same shot a few seconds later, revealing little more than a stone statue where Quint once stood. From this dizzying height, we helplessly watch as Miles falls to the ground dead, though who or what is truly responsible for his demise remains woefully unclear.

Has Miss Giddens been justified in her concern, trying to save these children from unholy evils? Are these merely ghosts of past traumas, manifesting as paranoid delusions? Does the kiss she plants on Miles’ cold lips come from her, or one of the spirits entering her body? Clayton offers few answers as this governess clasps her hands together in prayer, mirroring the image from the opening credits and sinking her into an unforgiving darkness. In their place, The Innocents simply haunts us with a stifled, neurotic madness, blurring the lines between sinful corruption and the efforts of those who obsessively seek to conquer it.

The Innocents is not currently streaming in Australia.

Have you seen Clayton’s Our Mother’s House(1967)?

I’ve not, this is my first Jack Clayton film. Worth catching?

It’s a must watch. There is nothing quite like it. And very relevant even today.

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green