Sergei Eisenstein | 1hr 22min

Much like the factory workers uniting against their exploitative managers in Strike, Sergei Eisenstein walks a very narrow line between anarchy and order. There is the temptation in both political and artistic rebellion to throw caution to the wind, tearing down traditional institutions with reckless indignation, and yet revolution for revolution’s sake is no way to pave a path for the future. As furiously impassioned as these Bolsheviks may be, unity requires discipline and willpower, ensuring every action is driven by ideological principles rather than emotional instinct.

So too does a rigorous formal purpose underlie every visual and editorial choice that Eisenstein makes in Strike, pragmatically applying the ‘methods of montage’ that he had innovated as a young film theorist. In approaching his craft with such mathematical precision, he effectively set the stage for the Hitchcocks and Kubricks of the future, understanding the compositional details from which profound sensory experiences of art are born. More specifically, it was the ability to cut from one image to another which he identified as cinema’s distinguishing feature, separating it from theatre, literature, and painting as a radical mode of creative expression for the twentieth century. By connecting two individual shots in this manner, a third idea is born which is not contained in either, but is rather delivered through the sum of both.

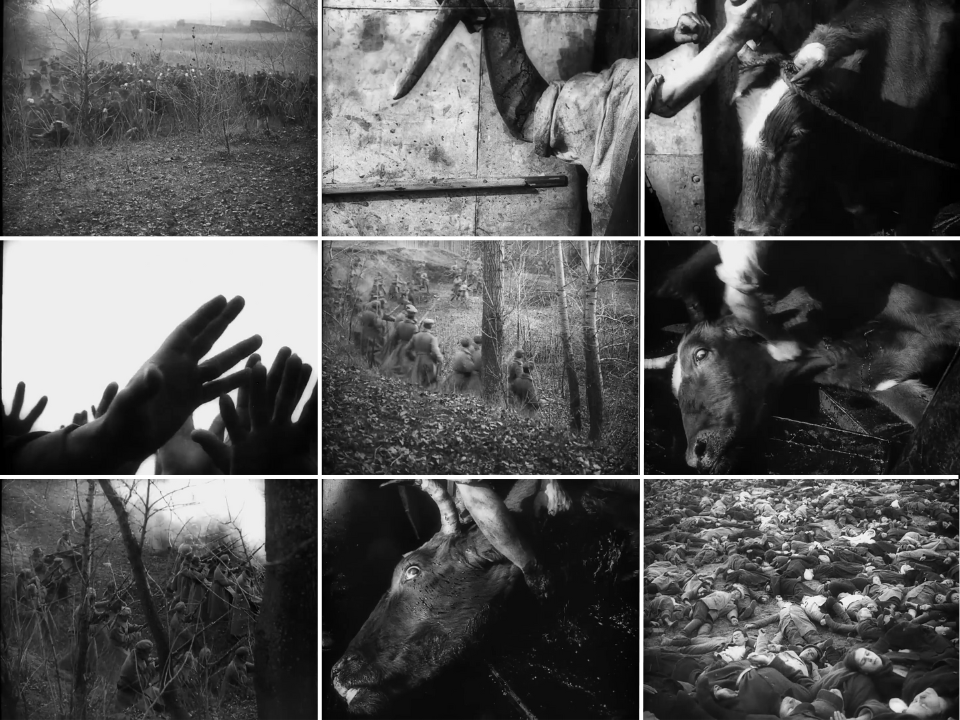

Eisenstein was not the only filmmaker of the 1920s to be experimenting in this arena, yet Strike was among the first features to demonstrate the enormous potential of Soviet Montage Theory, wielding cinema as a tool of propaganda. Set in pre-Revolution Russia, its narrative raises up the working class as their own heroes, planning to instigate a mutiny at their factory before the suicide of one labourer prematurely lights the spark. Close-ups on Yurik’s hands fastening his belt into a loop, a stepladder being kicked over, and the belt suddenly tightening around a metal beam tell his story through visual inferences, and from there Eisenstein executes a fervent set piece unlike any other that came before.

The length of the average shot in Strike sits a brisk 2.5 seconds, half that of the typical Hollywood film, though within this sequence it is even shorter. Machines are halted, feet run by, and tools are thrown into a pile, not to be picked up again until concessions are made. Quite unusually, there are no main characters here who stand above the fray. In true socialist fashion, strength instead lies in the masses, and as such Eisenstein dedicates many wide shots to his magnificent staging of their movements in powerful unison. The visuals are frantic, but never uncontrolled, propelling the scene forward as loose rocks are thrown through the foundry windows and the office gates are forced open. With nowhere left to hide, two unfortunate managers are carted out in wheelbarrows and tossed into a filthy river, at which point the temporarily satisfied crowd heads home.

Cinema is clearly more than just a narrative vehicle for Eisenstein, as this first day closes with an image that serves only to reinforce the strength of the movement – three labourers folding their arms and directing stern gazes at the camera, while a spinning wheel is projected over the top of them. Equally though, this double exposure technique is also later used to dissolve the image of a clawed hand over the strikers drawing up demands, threatening to crush their aspirations of justice. Their stipulations are nothing outrageous by modern standards – an eight-hour workday, 30% pay increase, civil treatment by management – but their momentary peace is nevertheless interrupted by troops seeking to disperse them.

Through Eisenstein’s parallel editing, their sit-down protest makes for a compelling contrast against the small group of wealthy shareholders gathering in a dark office, puffing cigars and using their demand letter to mop up a spill. There, the image of a lemon being juiced in a squeezer underscores the visceral brutality of the police’s attempted crackdown, once again pulverising the proletariats in the hands of their superiors.

When it comes to orchestrating cinematic collages such as these, Eisenstein is in a league of his own, calculating the length, placement, and type of each cut according to the needs of the scene. Dissolves do not necessarily indicate the passage of time, but are woven organically into montages like a legato musical phrase, while close-ups of incensed faces are alternately played with rapid staccato. Even lively flourishes of style are integrated here in the visual blending of undercover agents with animals, noting their shared features and mannerisms. As we examine their frozen images in a photo book, these spies suddenly spring to life with comical glee, tipping their hats at the camera before promptly leaving their individual frames.

If these editorial rhythms liken Strike to a symphony, then Eisenstein is its maestro, merging every cinematic element in orchestral harmony. Despite his aesthetic perfectionism extending to his mise-en-scène and camerawork as well though, it is an unfortunate consequence of the film’s brisk pacing that many critics also underrate the strength of its individual shot compositions, which deftly build out the expansive world of this factory and its surroundings. The industrial architecture of glass and metal juts out at geometric angles, weaves through machinery, and frames bodies that are always in motion, particularly in those recurring tracking shots past rows of men at work. There is rich detail to be gauged from the camera’s tighter framing of people and objects as well, gazing at an upside-down, spherical refraction of the town’s streets through a glass orb in a shop, quite literally turning society on its head as the strike drags painfully on.

The junkyard of half-buried barrels marks another superb set piece as well when the crooked King of Thieves is introduced, seeking five unscrupulous types to loot and set fire to a liquor store. Crawling out from the ground like worms, his ragtag followers set out to do his bidding, instigating a riot as gathering masses cheer on the violence. “They’re trying to incite us! Don’t give in to these provocations!” the wiser proletariats among them shout, though the authorities need little justification to enforce their own oppressive rule of law. Rather than turning their high-pressure hoses on the blaze, the firemen cruelly blast the crowd, with the military arriving sooner after to capitalise on this moment of vulnerability.

This is the unchecked influence of capitalists in a corrupt system, Eisenstein demonstrates, enforcing their own rule through the arms of the state. All throughout Strike, the first line of Vladimir Lenin’s epigraph declaring that “The strength of the working class is in its organisation” has proven consistently true, though now as their unity fractures, the relevance of its second part begins to surface as well.

“Without the organisation of the masses, the proletariat is nothing.”

The devastation which follows is unrelenting. It does not carry the bittersweet tragedy of Hollywood melodramas, nor the haunting ambiguity of German Expressionism, but this conclusive downbeat rather reflects the gut-wrenching national trauma which eventually drove the Bolsheviks to revolt in 1917. A child is tossed over the edge of a balcony, hands reach to the sky in desperation, and as these labourers and their families are rounded up like animals into a field, Eisenstein intercuts their massacre with the slaughter of a bull. It is a symbolic and editorial device that Francis Ford Coppola would later use in the final minutes of Apocalypse Now, though where that signified the death of a madman, here we mourn and rage at the murder of innocence.

We are right to feel disgust. Eisenstein would not have used such dehumanising imagery if he did not agree that the physical desecration of a living creature is a deeply disturbing sight to behold, yet only in witnessing this bold artistic statement might we experience a fraction of the repulsion the Russian people held towards their oppressors. While cinema was still young, few people understood its immense power in shaping political thought, and even fewer mastered this skill through a dextrous, virtuosic command of moving images as Eisenstein does here in Strike.

Strike is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

I intend to use Eisenstein as a bludgeon against a movie I think is terrible overrated. Eisenstein combined his images into various patterns: metrical, rhythmic, tonal, overtonal, and intellectual, often multiple at once. Nolan does not. It is inaccurate to describe Oppenheimer as a “3-hour montage” – the only montage features are superficial (rapid cutting and jumps in time). There is no meter, no rhythm, and rarely any tonal or intellectual association between shots. Oppenheimer is a conventionally edited continuity film, that just happens to be cut very fast, with an omnipresent score and many jump cuts. There is no structure or geometry to the scenes, like there is in Eisenstein.

And besides, there is no contest in visual beauty between Eisenstein’s compositions and Nolan’s.

Since you mentioned the channel “Moviewise” before, are you aware he has several videos wherein he talks about Oppenheimer? He praises the script (mostly), but criticizes bad directing, and Cillian Murphy’s performance.

Using Eisenstein as a yardstick for editing seems a little unfair – he is right there at the top and mastered the art of editing in a way so few others have. It seems a bit like arguing Fincher falls short because his visual perfectionism isn’t on the level of Kubrick. Eisenstein’s methods are incredibly effective, but they are still just a single theory – there were disagreements and variations even within filmmakers of the Soviet Montage movement.

I’ve seen those videos on Oppenheimer, but I do feel that one of the channel’s biggest flaws is a bias towards classical film language and writing (I still love that recognition though because it is very underrated in most other places). You especially see this when he misses on more neorealist films.

I wouldn’t argue that Nolan has as strong an eye for composition as Eisenstein, but I don’t believe that’s the only way to be a good director either. I’d be far more likely to defend Nolan’s editing over his mise-en-scene. Saying that he’s just all about fast cutting seems like a vast over-simplification – the way he uses parallel editing across multiple timelines in Oppenheimer, Dunkirk, Inception etc absolutely has structure to it.

Nolan’s large scale parallel editing has structure, and Moviewise even praises him in the screenwriting video for exactly that. But the design of local scenes often feels pretty random, without any shape or geometry, which undermines the effectiveness of the large scale editing.

I don’t know if I’d agree Moviewise is biased towards classical film. I think he has more experience and interest in those films, but he praised:

I think his criticism of Cillian Murphy is very apt. And what about the sloppy camera movements Moviewise points out?

My perspective is, that Nolan’s large scale cross cutting is very effective, but it’s undermined by formless and overly aggressive local editing.

Pingback: Sergei Eisenstein: Symphonies of Soviet Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green