Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 43min

Marriage within the Kohayagawa family takes on multiple meanings throughout The End of Summer, always dependent on the individual in question. For younger daughter Noriko it is an aspiration hindered by her sweetheart Teramoto’s decision to move away for work, while her elder sister Fumiko performs her duty loyally, raising a son with her husband Hisao. The pressure for their widowed sister-in-law Akiko to remarry is also quietly mounting, even as she quietly resists with the sincere acknowledgement that her youth is long gone – not that patriarch Manbei sees this as an issue when he controversially tries to reconnect with his old mistress. A widower of his age should not be considering the prospect of marriage, his family proclaims, lest he should embarrass them all.

As is the case in most Yasujirō Ozu films, Japanese tradition is at the forefront here, merging The End of Summer’s rigorous form, style, and content into a gentle meditation on those longstanding cultural values that have ensured stability across generations. Where his penultimate film sets itself apart is in the astounding elegance of the execution, even by his own standards. In terms of pure visual storytelling, this competes with only a handful of his greatest works, while pushing his geometrically precise style forward through rejuvenating colour photography.

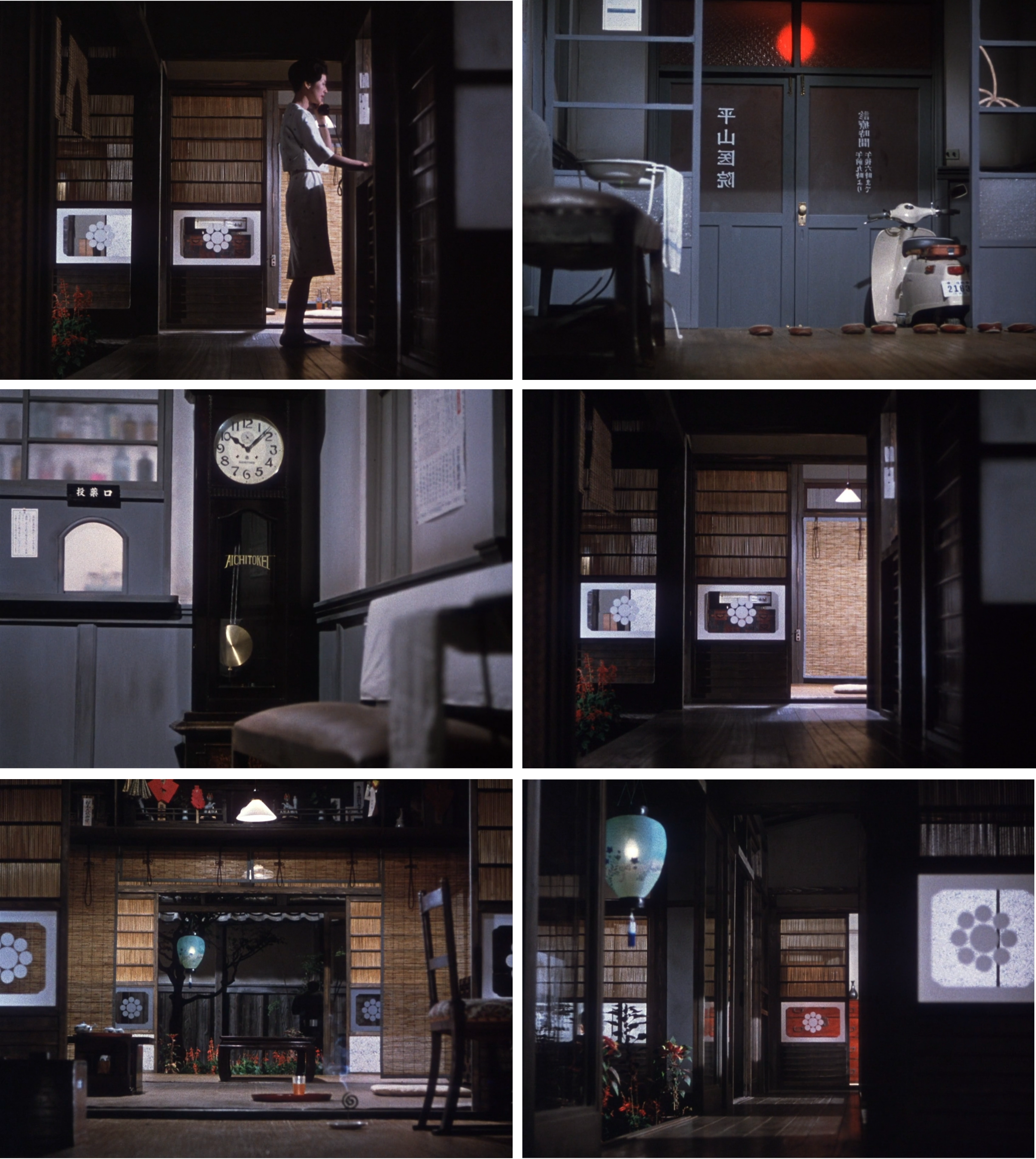

Ozu’s layering of frames through corridors and doorways remains one of his most potent visual devices here, often containing his characters within the spaces of work, leisure, and domestic duty which define their day-to-day routines. There is often an extraordinary graphic harmony between people and their surrounding décor, symmetrically dividing a table at one of Noriko’s work lunches by gender, while running a pattern of brightly coloured bottles beneath them parallel to their staging.

The End of Summer’s mise-en-scène also transcends conventional blocking choices, often suggesting the presence of specific characters despite their physical absence. When we transition into a scene with Akiko at an art gallery for instance, Ozu gently delivers a montage of floral paintings in an art gallery, while on a broader level he represents the entire Kohayagawa family through the brown, earthy tones that encompass them. Within their home, dark wooden flooring, furniture, and panelling are the dominant aesthetic, complementing their light bamboo drapes and striking an extraordinary contrast against their exquisitely patterned wallpaper and textiles.

As for Manbei himself, his personality and power are most strongly signified in the family sake brewery, often seen with barrels leaning obliquely against its wall in Ozu’s pillow shots. Their contents are the foundation of his small business, though in this modern era its future is looking frighteningly uncertain, as the need to merge into a larger corporation seems more inevitable with each passing week.

When Manbei suffers a heart attack, these shots consequently draw a parallel between the health of his body and his company. As Noriko rushes to call an ambulance, Ozu cuts through a series of familiar locations in their home that are now gloomily dimmed and emptied, before returning to the brewery’s exterior where the absence of barrels is poignantly noted. The graveyard shot that is additionally inserted here isn’t to be passed over either – Ozu’s careful editing weaves a mournful foreboding in the wake of this sudden illness, quietly hinting at the tragedy that has already taken the family’s beloved mother, and which will soon claim their patriarch and business as well.

Throughout Ozu’s career, the encroachment of the modern world into traditional Japanese spaces has steadily become more central to his narrative conflicts, even as he maintains a nuanced standpoint on the issue. With a piece of the Kohayagawa family’s identity at stake, the threat of post-war industrialism is felt especially deeply here, yet at the same time Ozu savours the incongruence of this cultural clash. The blinking neon lights of Kyoto’s cityscapes are searingly beautiful, while views of temples through Venetian blinds and pagodas peeking over tiled roofs further develop the uneasy interactions between Japan’s past and present.

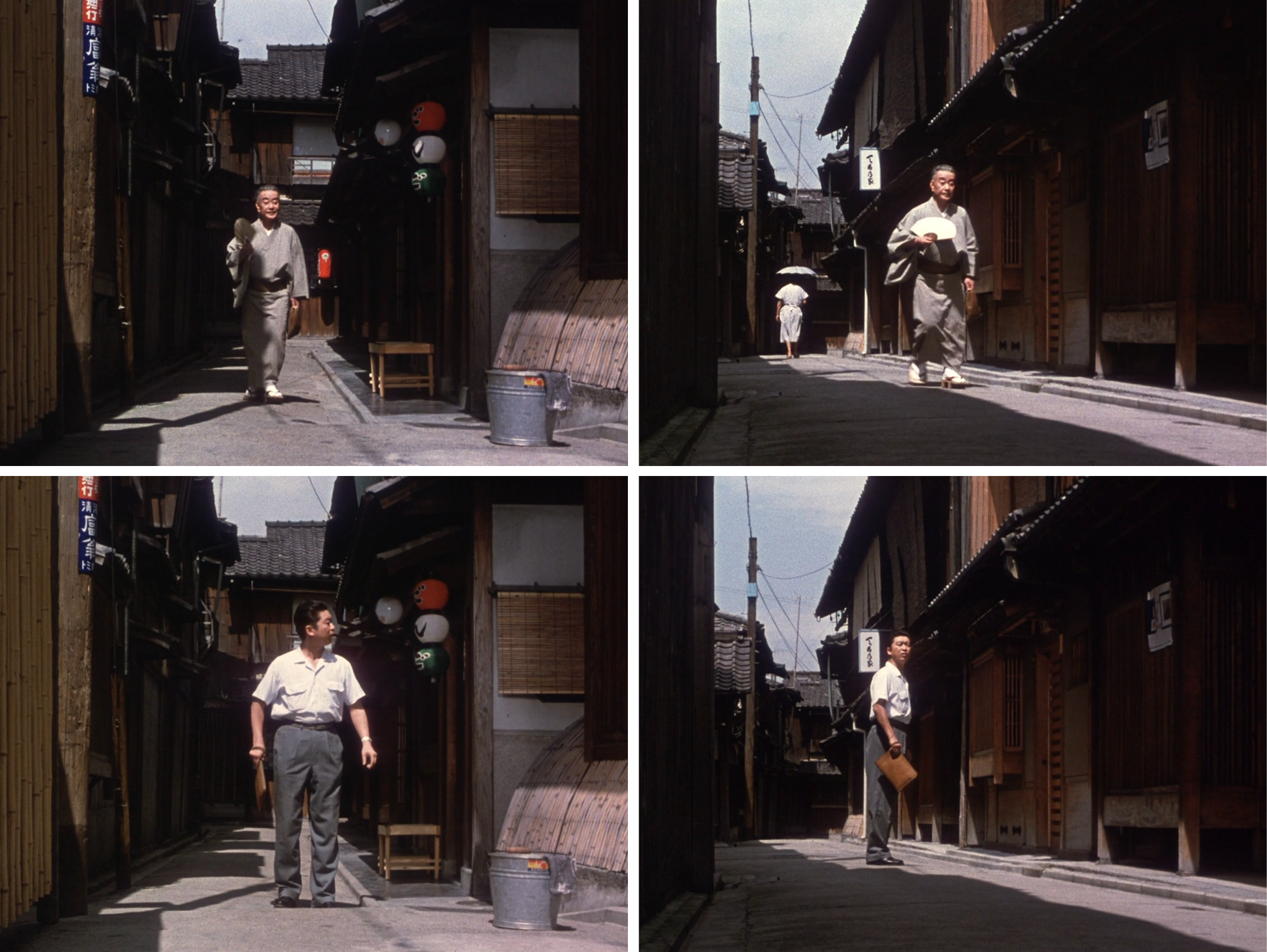

Quite unusually though, it is not just the younger generations subverting cultural customs in The End of Summer, but even Manbei himself. Every so often Ozu dismisses his characters’ polite reservations with glimpses of spirited humour, watching the elderly sake brewer play hide and seek with his grandchild, and elsewhere try to shake his employee’s tail while running off to his mistress’ home. His children’s concerns about this rekindled romance are understandable given its history, though now that their mother has passed, so too can we understand Manbei’s renewed desire for companionship.

It is obvious upon meeting Tsune that we realise she is no wily seductress, but just another lonely parent seeking love, and ultimately proving her dedication to Manbei as she nurses him through his sickness. Happiness and fulfilment can clearly be found outside the family unit in The End of Summer, even if certain relationships are left ambiguous, such as the question of whether he fathered her daughter Yuriko. The rebellious streak that he and Yuriko both share only supports this speculation, particularly manifesting in her as a rejection of Japanese culture and adoption of a heavily Westernised lifestyle. Rather than the loose-fitting and slimming garb worn by Manbei’s daughters, she wears bright, eye-catching dresses that accentuate her curved figure, and her dating life primarily revolves around white American men.

The two sequences where Ozu takes the Kohayagawa family outside the city and into the countryside thus mark a reprieve from this modern cultural conflict, even if it is exchanged for profound mourning in both instances. In the first instance, they hold a memorial service for their late mother in Arashiyama, where Ozu’s pillow shots turn their focus to forests and hills that have barely been touched by human civilisation. The second time they venture beyond their home though, the grief is far more potent, commemorating the passing of their beloved father.

The small appearance of Ozu regular Chishû Ryû as a farmer observing the crematorium chimney with his wife is notable here, despite there being no direct interaction between them and our main characters. Judging by the crows gathering along the river where they work, they surmise that someone has died, and soon their suspicions are confirmed when smoke from that giant pillar begins rising into the air. “It’s not a big deal if an elderly person were to have died, but it would be tragic if it were somebody young,” the woman ponders, while the man takes a more positive spin on her indifference.

“Yes, but no matter how many die, new lives will be born to take their place.”

It is merely the cycle of life, his wife acknowledges – a comforting assertion given the confirmation in these final scenes that the Kohayagawa brewery will indeed be sold off, ending an era in this family’s history. No longer do these adult children wear light colours and delicate patterns, but instead exchange them for pitch-black, funereal garments. Even after they leave the graveyard, the severe imprints they cast against the pale blue sky poetically resonate into Ozu’s sombre final shot, revealing two crows cawing upon a pair of headstones. They are the grief of the living that lingers with the deceased, but so too are they the souls of husband and wife joined in death, marking the resting spot where their bodies lay. Perhaps the celebrated traditions of marriage and family can secure a longstanding stability through this loss, yet The End of Summer does not underestimate the sorrow that it entails, composing wistful lamentations of life’s transient, bittersweet joys.

The End of Summer is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Did you catch that they were singing to the beat of “Oh, my Darling Clementine” at the coworker party ? Neat little easter egg to further the commentary on Western culture seeping through modern Japan.

Great detail there!

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green