Jean Eustache | 3hr 40min

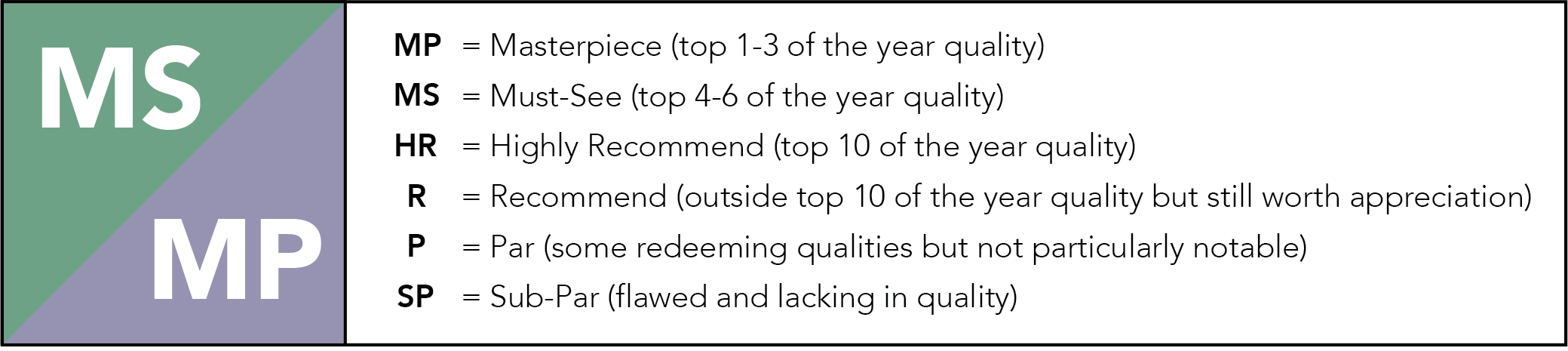

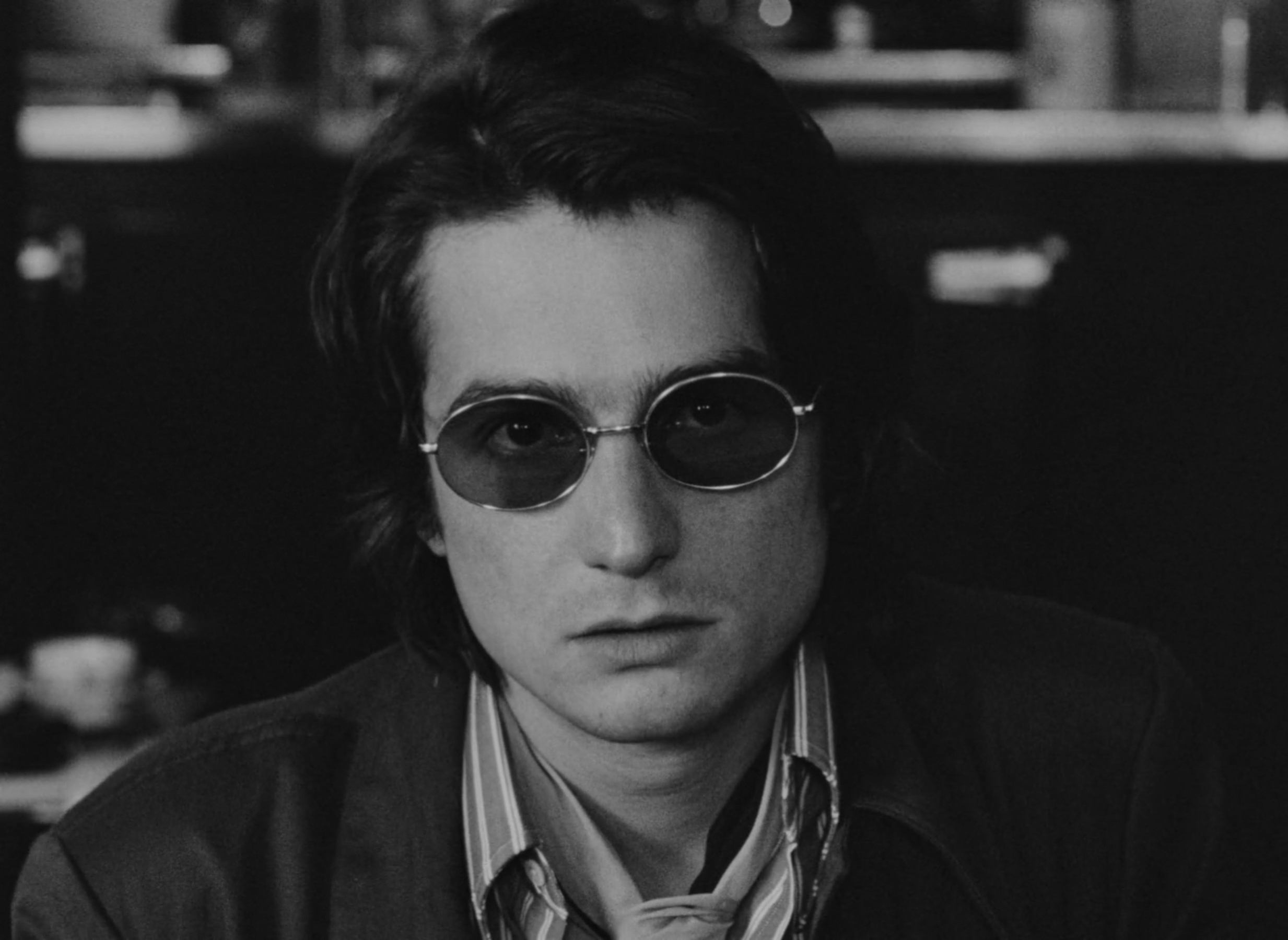

In the Les Deux Magots café where intellectuals and artists of Paris gather, Alexandre tries a little too hard to blend in with the crowd. He speaks eloquently of the May 68 protests, classic filmmakers, and the state of modern relationships, yet he never quite drops the tone of cynical self-importance, barely masking the lack of substance in his political philosophising. When invited to dance at a club, he justifies his refusal with two excuses – “It bores me, and I have no money” – though it is plain to see the self-consciousness which underlies his haughty indifference. As long as he is in control of his environment, then he can maintain the hypocritical pretence that compartmentalises his misogyny, sexuality, and desperate desire to be taken seriously – an effort which is severely threatened by the meeting of his two girlfriends.

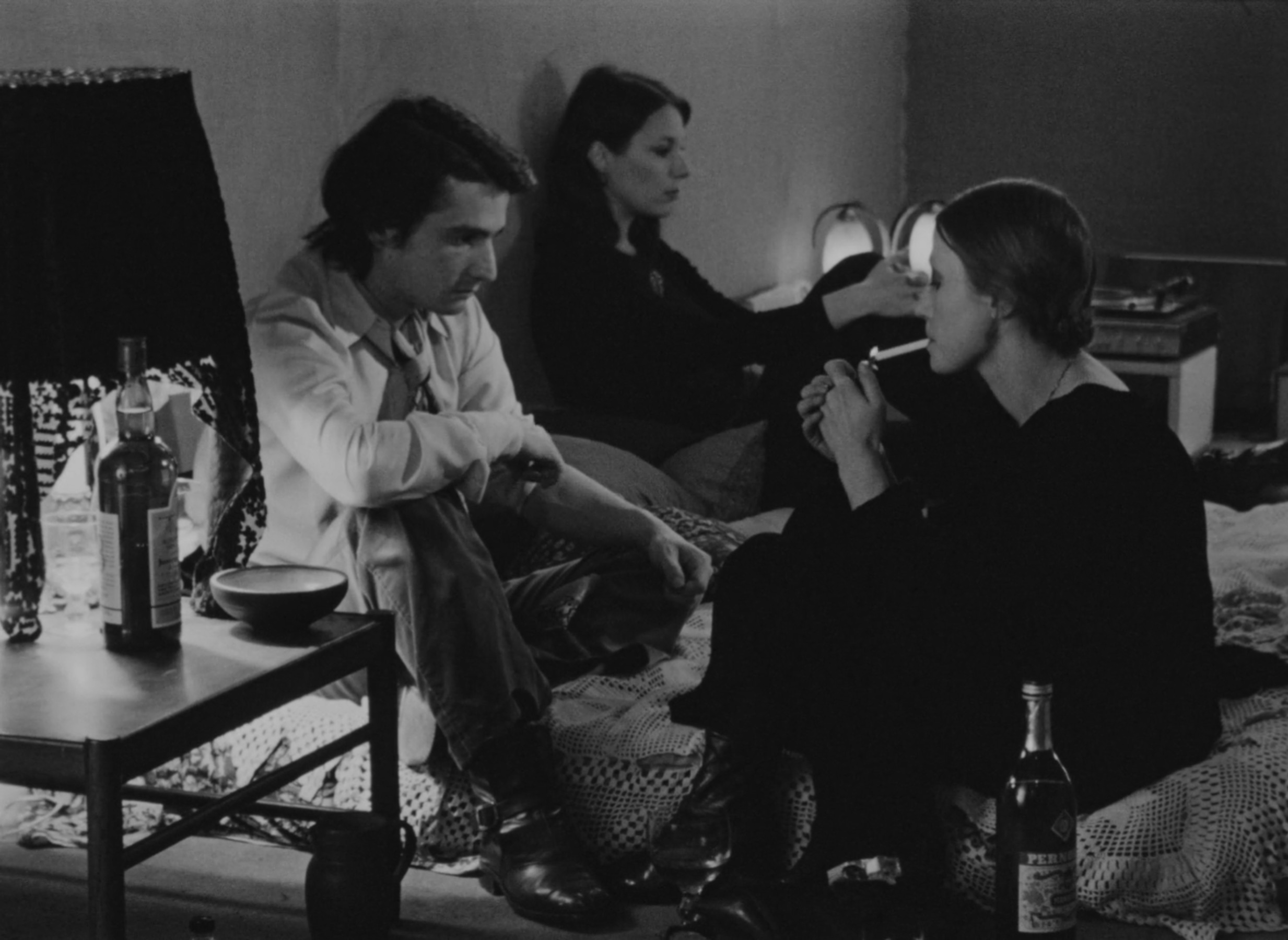

Sigmund Freud’s infamous Madonna-whore complex is baked right into the title of The Mother and the Whore, calling out the male psychological desire to pursue both love and sex, but never with the same woman. To Alexandre, Marie is the reliable caretaker who he shares a small, shabby apartment with, spitefully tolerating his affairs. Meanwhile, Veronika is the promiscuous paramour whose no-strings-attached attitude fools him into thinking she lacks any greater depth than what she presents on the surface. Where both women overlap is in Alexandre’s flattening of their identities, believing they only exist to serve his conflicting desires for stability and excitement while rendering their emotional needs inconsequential.

“You don’t love me. You love Marie. You live and sleep with her, you wash with her, you shit with her. You love a woman and fuck another.”

The extent to which the director based this character study on his own youth is clearly defined by Jean Eustache himself, who openly named the real-life people that these women were based off. Though he admitted more freely to his weaknesses than Alexandre, he nevertheless shared similar passions and anxieties, drifting around the edges of the French New Wave during its peak with featurettes and documentaries before falling victim to creative block. The concept for The Mother and the Whore struck him very suddenly in 1972, at which point there was no holding back his immense ambition for his first feature film, using its nearly four-hour runtime to apply an intensive focus to the lives of three young adults and their juvenile struggles in love.

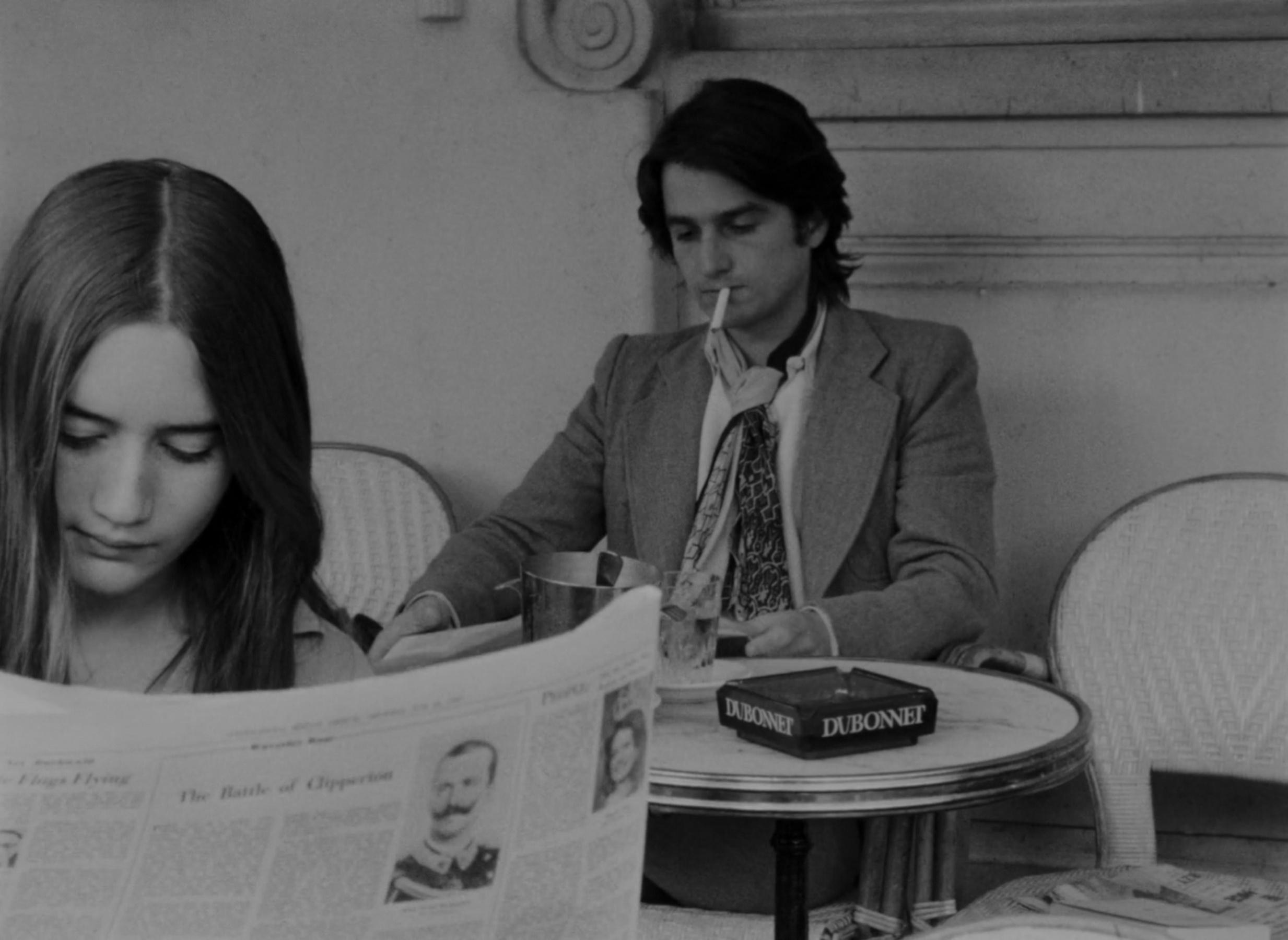

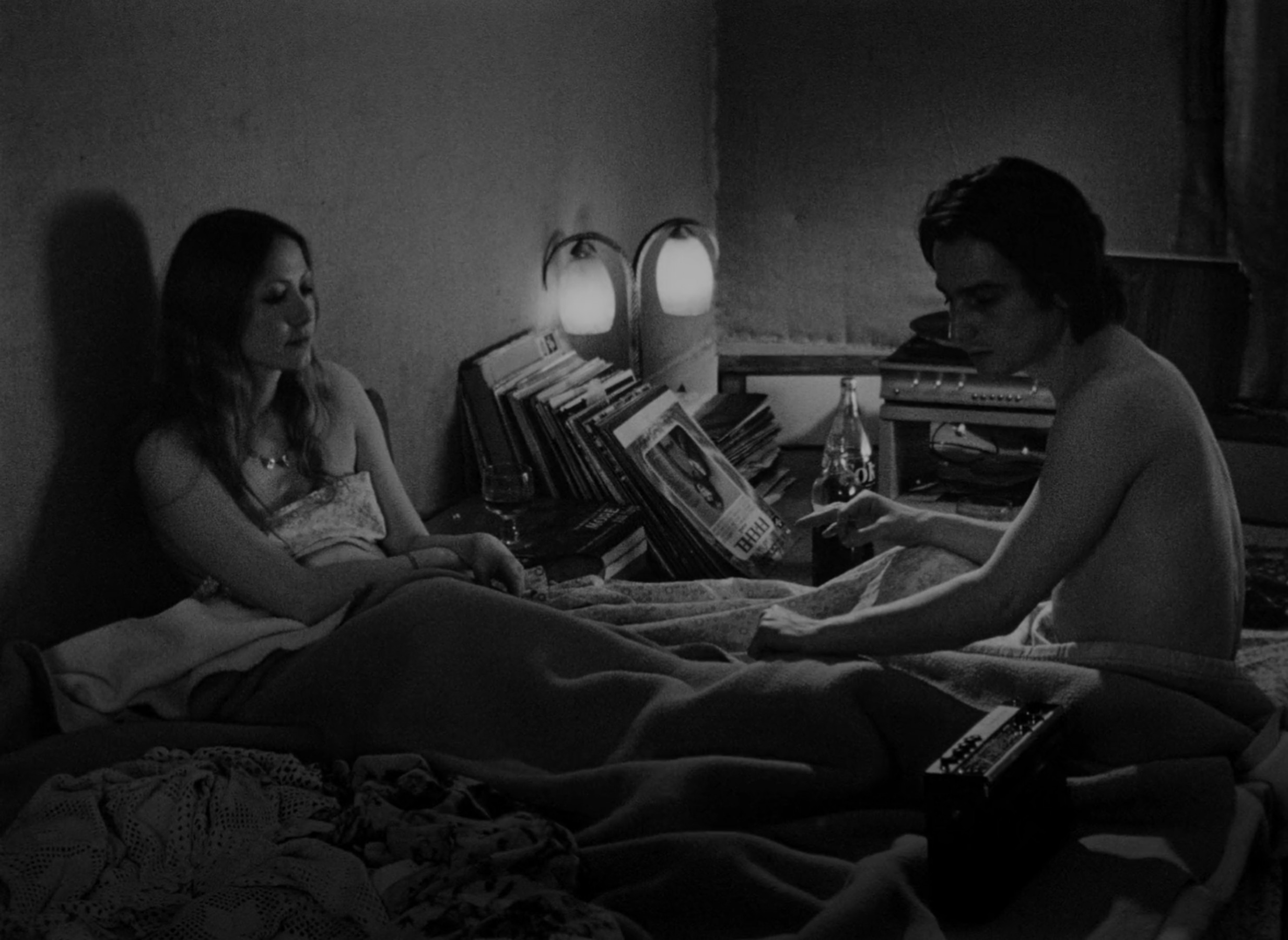

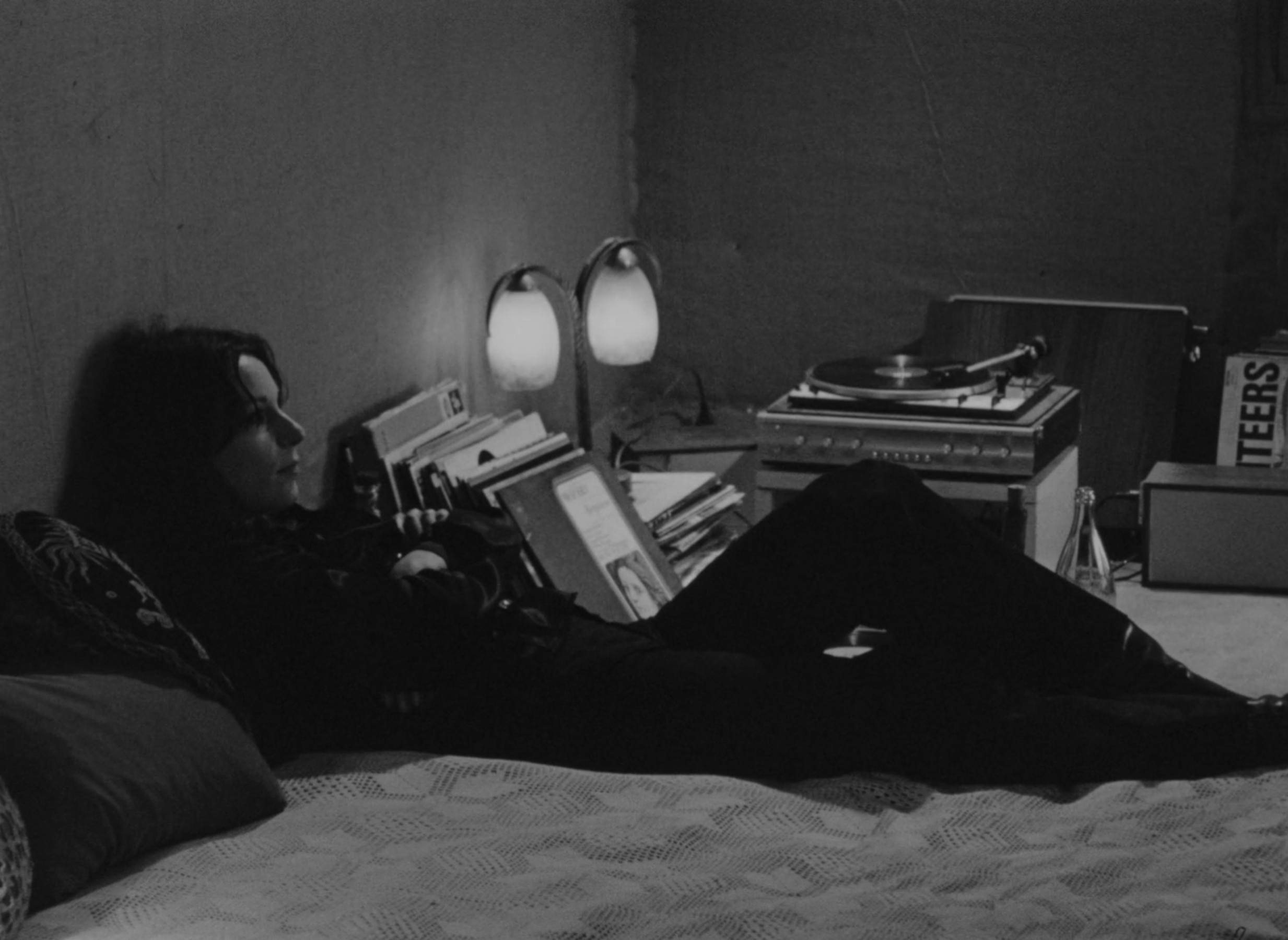

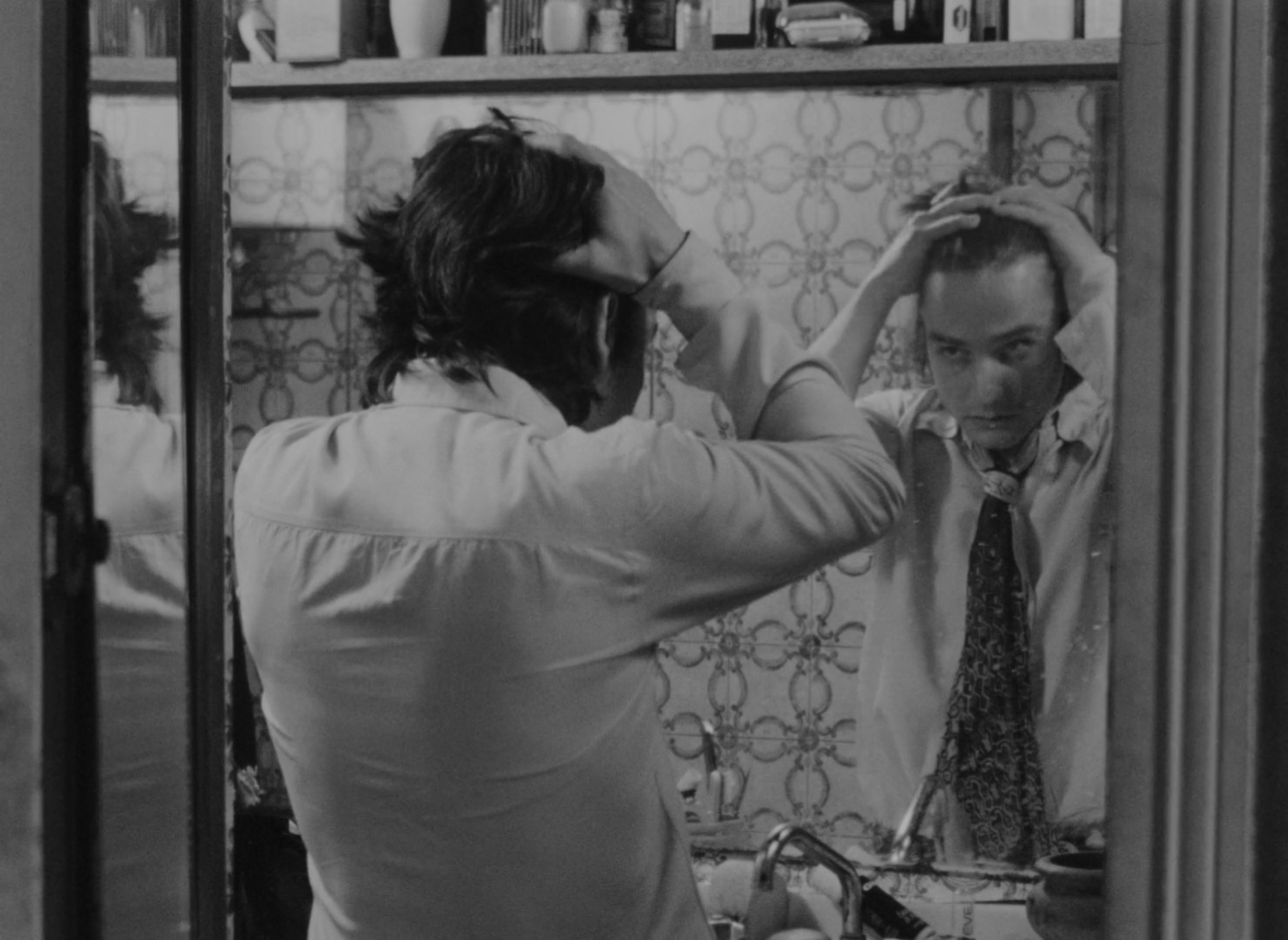

Production for Eustache’s epic drama lands firmly outside the span of time that the French New Wave covers, yet it still couldn’t be more aligned with the movement’s subversive ideals. Shot in the streets and cafés of Paris on grainy black-and-white film stock, Eustache achieves a gritty, urban naturalism in his compositions and handheld camerawork, and even lets the noise of passing cars occasionally drown out his characters’ conversations. City lights bouncing off the Seine become a muted backdrop to Alexandre and Veronika’s meeting on a bench, and their threadbare apartments are completely empty of shelves, bed frames, and decorations, leaving clutter to gather on the floors instead. Eustache’s long takes prove to be crucial in appreciating the minimalist beauty here, as well as the dedicated performances of his actors, whether it is Bernadette Lafont crying to the entirety of Edith Piaf’s song ‘Les Amants de Paris’ or Françoise Lebrun commanding a powerful close-up in Veronika’s climactic eight-minute monologue.

Ultimately though, Jean-Pierre Léaud’s thorny portrayal of our two-faced hero marks the greatest acting accomplishment in The Mother and the Whore, with his casting nodding to Eustache’s colossal influences Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. As insufferably verbose as he may be, it is telling that the only thing he listens to other than his own voice is his vinyl collection of French classics and British rock, offering those artists a respect that he never affords anyone else. When Veronika notices his fondness for music and sings a poignant love ballad in a rare moment of vulnerability, it is comical just how jarringly he changes the topic by turning on his favourite radio station, landing right in the middle of a segment railing against the laziness of modern society.

Smugness evidently goes hand-in-hand with insecurity for Alexandre, and it isn’t hard to see how his loquacious brand of intellectual pretence would later go on to shape the characters of Woody Allen and Richard Linklater films, especially considering the gaping chasm that lies between his narcissistic ego and feeble masculinity. It is much easier for him to blame women at large for his romantic struggles than to turn a critical eye inwards, as he shallowly longs for an era with old-fashioned values while remaining ignorant to the fact that he still would have been just as undesirable back then.

“I wish I had known the days when girls, in the streets of our cities, on our country roads, swooned over soldiers. The prestige of the uniform. These days they swoon over sports cars. These days, young businessmen, young executives, professionals, have replaced the military. I’m not sure we’re better off.”

The cognitive dissonance needed for a radical leftist like Alexandre to make such a conservative statement is staggering, though clearly his politics are as fickle as his choice in women. Neither Marie nor Veronika have entirely figured out who they are yet either, but at least within The Mother and the Whore they develop a self-awareness that their common boyfriend never quite finds the courage to face. When the three of them enter a polyamorous relationship, Marie and Veronica are united in a mutual understanding that leaves Alexandre deeply discomforted, helplessly watching his psychological division between love and sex slowly erode. As it turns out, these women are far more complicated than the neat boxes he has designed for them. With Marie’s façade of stability fading, she not only finds the freedom to explore her sexuality, but also unleashes a pent-up rage she had previously contained. Similarly, Veronika’s claim that she is only after sex from men completely disappears when she reveals her jealousy towards Marie and tearfully laments the emptiness of her carnal pursuits.

“If people understood, once and for all, that fucking is shit. That the only thing that’s beautiful is to fuck because you’re so in love you want to a conceive a child who looks like you, or else it’s something sordid. We should fuck only if we’re in love.”

Alexandre is lucky to have two girls who love him and like each other, Veronika declares, but still happiness eludes him. After all, if he were to accept this state of affairs then he must also relinquish control of a dynamic that preserves his simplistic world view and protects his ego. Perhaps this is why Veronika’s unplanned pregnancy spurs such a rapid, uncharacteristic change of heart, sending him impulsively running back to her apartment to propose, and hopefully reduce this complicated love triangle to a traditional two-way relationship.

Predictably, his regret is almost instantaneous. For as long as his arrogance keeps him from addressing his own inhibitions, he will never find fulfilment in romantic intimacy, especially when it is contained within an institution as rigidly traditional as marriage. As Alexandre sinks to the floor in the final seconds of The Mother and the Whore, he has no lengthy monologue or deflection to steal back control. Eustache simply concludes this film of endless verbal debate with bleak, dampened silence, cynically anticipating the birth of a dysfunctional family, and its fathering by an infantile egoist who cannot understand the fundamental virtue of selflessness.

The Mother and the Whore is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Oh wow, I always wondered how La Maman et la Putain would fare on here or Cinema Archives according to the criteria, and tbh I was excepting an HR at best and most likely an R, since it’s so purposely devoid of style and anti-cinema. More than Rohmer who already gets penalized for it. Still, there is a formal consistency on the use of close ups where people talk at the camera I suppose.

Not complaining though, masterfully written film and extremely powerful performances –even with Léaud acting very stilted and mannered, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was intentional from Eustache– Lebrun’s monologue touches Falconetti heights as far as I’m concerned.

I had to first watch it on some 480p stream of an old shitty scan, glad it’s available widely in good quality now. I’m waiting for Criterion to release that new transfer on disc.

Thanks Vaanilla, it is very much a screenplay driven film but it has really great form to it. I’ve not seen a lot of Rohmer, but the two I have watched I’ve been very impressed by, including The Green Ray which I rate much higher than Drake (although it seems he hasn’t seen that one in a while since he hasn’t given it a proper grade). I sort of see both Eustache and Rohmer in the same category as Linklater, who is given his due over there despite not being a remarkable visual stylist. It’s great to see films like this get the Criterion treatment!

This and Day For Night both premiered at the Cannes film festival in 1973 starring Leaud

Pingback: Jean Eustache: Masculinity in the Making – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green