Federico Fellini | 2hr 19min

The outlandish matriarchal society that middle-aged philanderer Snàporaz wanders through in City of Women is not quite the grand feminist statement that one might expect, but rather a self-deprecating cinematic tool for Federico Fellini to pick at his own masculine insecurities. The women who occupy this secluded region of Italy are militant caricatures, calling the missionary position a “sociocultural oppression” and claiming wrinkles are a male invention, though they are specifically the type of radicals that one might invent as a straw man for the sake of ridicule and derision. As Fellini reveals in its closing scene, they are little more than figments of Snàporaz’s unconscious mind as he naps on a long-distance train journey, pieced together from real women travelling with him in true The Wizard of Oz-style.

Still, every so often, a sharp blade of truth slices through Snàporaz’s uneasy fantasy. He has smirked at and talked down to the attendees of the feminist convention that he has stumbled across, but he can only remain hidden in the crowd for so long. The speaker to draw him into the spotlight is the woman who he followed into this mysterious city, and now as she addresses her audience, she eloquently raises him upon a pedestal of judgement.

“Our efforts here have been useless, sisters. The eyes of that man, presently among us with that look of feigned respectability, of one who desires to know us, understand us because he insists it can better our relationship. We are only a pretext for another of his crude animalistic fables. Another neurotic song and dance act. We’re his chorus, his hula hula girls, his fiends. We enhance his show with our passion, with our suffering.”

If Marcello Mastroianni is once again performing the role of Fellini’s surrogate here, then it is plain to see the self-criticism in this passage. As a filmmaker, he recognises his own tendency towards the objectifying male gaze, while as a husband, the guilt of his affairs weighs enormously on his conscience. Only someone who has been inside his mind could design a nightmare so specifically targeted to these doubts, and only Fellini could do so with the edge of dark, chaotic surrealism present in Snàporaz’s emasculating journey through City of Women.

The visual magnificence which once guided us through the absurd dreamscapes of Satyricon and Casanova is far more inconsistent here than we are used to with Fellini, though his most familiar stylistic trademarks still make an impact. The zooming, panning, and drifting camera movements through crowds of people are stifling, while imposing set designs totally consume Snàporaz, defining each episode in this narrative with renewed visions of Kafkaesque madness and self-reflection. As he slowly descends a giant slide in a lonely amusement park, he watches memories of his childhood crushes pass by in strange exhibitions, and in a miserable, grey courtyard of portraits and candles he finds himself speechless before a panel of female judges.

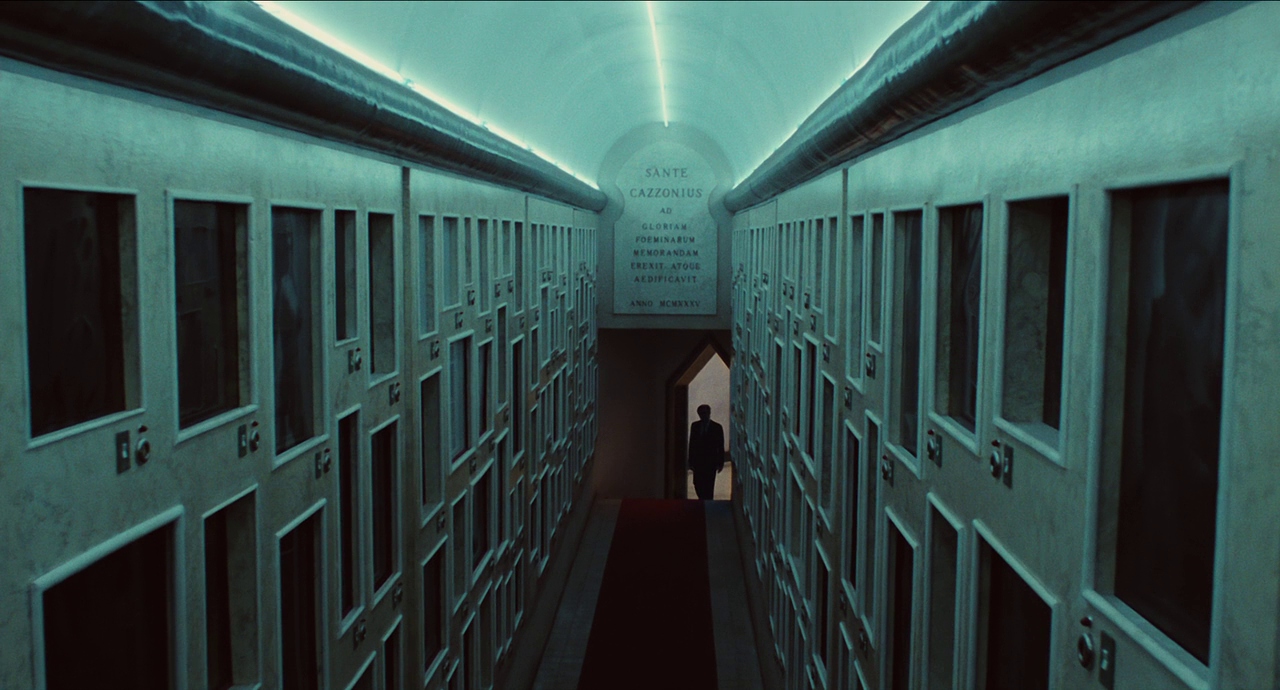

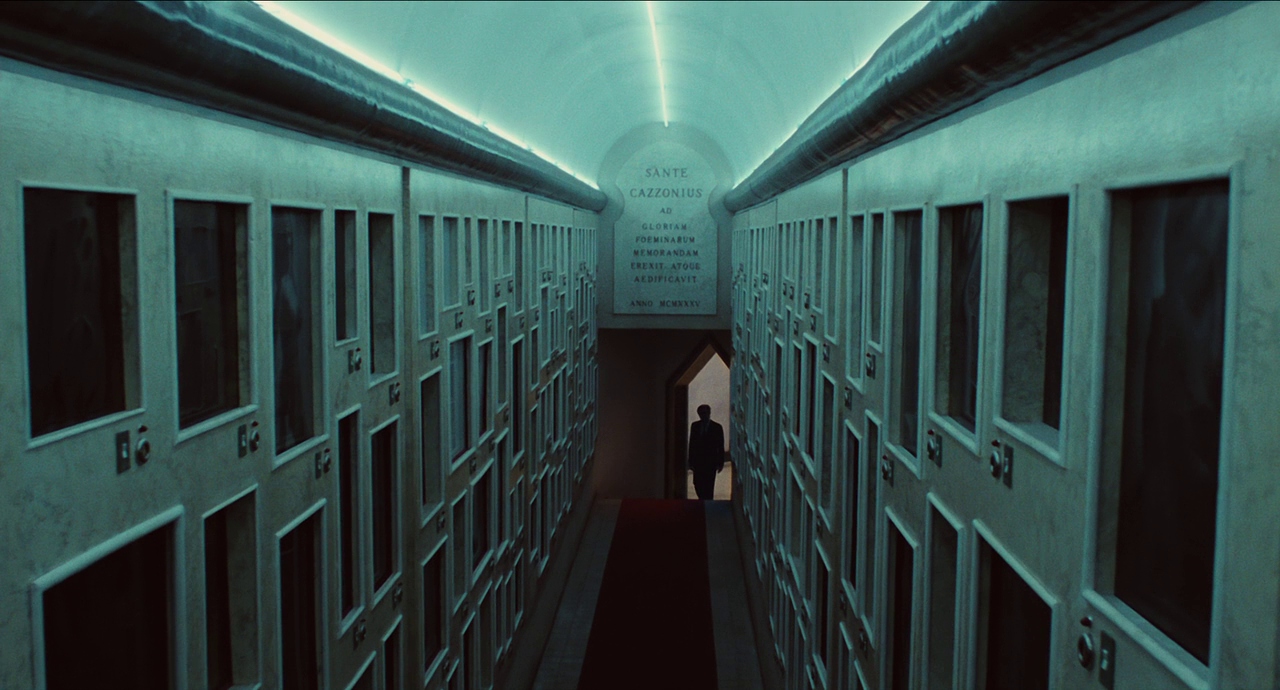

The manor of Dr. Xavier Katzone where Snàporaz seeks refuge is the set piece where Fellini’s absurd spectacle lifts off though, encompassing the bewildered outsider in an eclectic mix of patterns, textiles, and phallic sculptures. Even the spires on the fence outside were designed with that resemblance in mind, the doctor explains, consciously rebelling against his matriarchal rulers. Among the more peculiar displays here too is the long, arched corridor lined with photos of every woman he has slept with, each individually lighting up and playing explicit audio of their encounters.

In effect, Snàporaz’s vanity takes physical form in Dr. Katzone, whose manor is essentially a shrine dedicated to himself. True to his ostentatious arrogance, the doctor even hosts a celebration of his ten thousandth sexual conquest that evening, complete with a giant cake and enough candles to burn down the entire building. Fellini continues ramping up the absurdity through this sequence, lingering on one guest’s party trick of sucking up coins into her vagina aided by some reverse photography, but once again the insanity comes to a halt when Snàporaz comes face-to-face with his own shortcomings – this time manifesting as his ex-wife, Elena. The bitterness in their quarrel is only drowned by a shared sorrow over their festered love, as she leaves him to wonder whether there may be some possibility of redemption in his future.

“There may still be a chance, if you wanted. Or are we too old to be young again, you and I?”

Perhaps this is why when Snàporaz is eventually put on trial for his masculinity and dismissed to go free, he nevertheless chooses to face his mysterious punishment anyway, following a corridor into a boxing ring with a giant, stone tower in the centre. “Shake her, break her, find her, lose her, open her, close her, love her, kill her, remember her, forget her,” the crowd of women chant, encouraging him to climb it and make love to the supposedly ideal woman at the top. Halfway up the ladder though, he is not so certain that this is necessarily what he desires.

“If you existed, would you be my reward or punishment? Please, let me go. Have mercy. Get me out of this mess. What good am I to you? I don’t need you, and vice versa. Could it be we’ve already met but that I don’t recognise you? My first love? No, you must be somebody new, someone born out me.”

At the top he finds only Donatella, the sole woman to have shown him kindness in this city, and a hot air balloon that has taken her form. Perhaps this is his escape then, Snàporaz half-correctly presumes, before she loads a machine gun and sends him plummeting to his death.

Back on the train, he jolts awake. “You’ve been mumbling and moaning for two hours,” the woman he previously followed off elucidates. The reveal would almost seem like a copout if the seeds of this journey were not so evidently planted within Snàporaz’s subconscious, sprouting into deliberations that he may either disregard as pesky nightmares or carry with him into the real world. As the train hurtles into a tunnel though, Mastroianni does not grant such clear answers, leaving us with an expression that could be either peaceful acceptance or smug complacency. Clearly the layers of insecurity and madness which City of Women is founded upon are slippery for any man as conceited as Snàporaz or even Fellini himself to grasp, composing an imperfect yet compelling portrait of masculinity threatened only by its haughty, self-destructive hubris.

City of Women can be purchased on Amazon.