Max Ophüls | 1hr 45min

French noblewoman Louise regularly visits the local Catholic church in The Earrings of Madame de… to pray for prosperity, though the tenets of her faith do not fall in so neatly with the Christian doctrine of 19th century Europe. The intended recipient of her invocations is not necessarily God, but rather a fatalistic universe which has already miraculously proven itself to be on her side, whether by chance or providence. As for the sacred charm which she venerates as an icon of good fortune, one needs to look no further than those precious diamond earrings which she had previously tried to part with to pay off her enormous debts, and yet have since returned through pure happenstance. This of course can’t just be coincidence, she decides, and thus these pieces of jewellery are imbued with a mystical sentimentality that she alone has conceived of in her mind.

If destiny does exist within The Earrings of Madame de… though, then it isn’t one that can be influenced simply through prayers, wishes, or talismans. It is cold and indifferent, guaranteeing that whether it is Louise’s husband André or her paramour Fabrizio who ultimately wins their contest, she will be left heartbroken by the loss of the other. Max Ophüls may have been German-born, and yet these lyrical contemplations of fate’s ironic passages position him as perhaps the greatest inheritor of France’s poetic realism in the 1950s. Moreover, this lofty status is only strengthened by his use of Jean Renoir’s favoured cinematographer Christian Matras, crafting long, elegant tracking shots that carry the legacy of his cinematic forefathers.

There are few visual devices that match so gracefully to the film’s predeterministic perspective as this, seeing the camera trace the winding paths of objects and people before settling on extraordinary frames that Ophüls has perfectly arranged as the camera’s destination. Right from the very first shot, he is already laying the groundwork for this overarching aesthetic in a 2-and-a-half minute long take that begins on those fateful earrings, follows the movement of Louise’s hands through dressers and armoires, and finally catches her reflection trying them on in a small, oval mirror. As a result, she is immediately introduced as a woman defined by her abundantly lavish possessions rather than her innate qualities or relationships.

Ophüls is not one to cut corners on his production design either, consuming Louise in a cluttered opulence that evokes Josef von Sternberg’s busy mise-en-scène, yet without the harsh angles of his expressionism. Hanging around the edges of her bed are thin gauze drapes patterned with floral emblems, often framing her face or lightly obscuring it as the camera peers into her intimate domain, while elsewhere dining tables laden with candelabras, glassware, and bottles obstruct our view from low camera angles. Behind the seated guests, a giant mirror stretching the length of the wall turns the ballroom dancers into a lively backdrop, surrounding Louise with upper-class splendour on every side. Even when she grows depressed, she remains totally consumed by this material lifestyle, as Ophüls sinks her body into a large armchair that leaves only her head visible at the bottom of the frame. Just as exorbitant wealth incites Louise’s romantic interest, so too does it stifle relationships, including her marriage to André whose large bed sits in the same room far away from her own. Though she has taken his surname, Ophüls underscores its complete irrelevance to her identity all throughout The Earrings of Madame de…, frequently censoring it with diegetic interruptions and convenient camera placements.

That the earrings which Louise decides to sell were a wedding gift from André speaks even more to her disinterest in their marriage, motivating her pretend to lose them during a night out at the theatre, before actually pawning them off to local jeweller Mr Rémy. At least her husband returns the sentiment, or lack thereof, as once Mr Rémy secretly sells them back to him, he presents them as a farewell gift to his mistress Lola before she leaves for Constantinople. During her travels, they are again used to pay off personal debts, winding up in the hands of another jeweller who in turn sells them to a passing traveller – handsome middle-aged gentleman, Fabrizio. That he should later run into Louise twice in the span of two weeks and eventually fall in love with her seems too strange of a coincidence, and when he unassumingly gifts her the earrings that she once owned, she too recognises the remarkable journey they took to return home.

Within this web of affairs though, André is no fool. He indulges Louise’s pretence of losing her treasured earrings for some time despite knowing the truth through Mr Rémy, and his observations of her apparently platonic relationship with Fabrizio stoke suspicions. From his position of power and knowledge, he maliciously toys with her, and even forces her to give the earrings to his niece who has recently given birth. Quite remarkably though, Ophüls sees them sold to cover debts for a third time in his narrative, and thus Louise is given the chance to buy them back from Rémy much to her husband’s dismay. After all, no longer do they represent their matrimonial union, but rather her relationship with Fabrizio which has reliably conquered the stacked odds against it.

With Ophüls’ dextrous camera manoeuvring the ups and downs of this affair, it isn’t hard to fall prey to Louise’s romantic idealism either. The coordination of his cranes and dollies through scenes with multiple actors become a delicate dance of blocking – quite literally too in a montage that breezes through several weeks of illicit encounters at balls. As Louise and Fabrizio waltz through large crowds, the camera delicately weaves with them, drifting further and closer to their quiet conversations in rhythmic patterns. With each individual dalliance being linked by long dissolves, Ophüls creates the impression of one long, uninterrupted dance, blissfully contained inside a dream that Louise will keep prolonging for as long as destiny wills it to live.

As far is Louise is concerned though, this is barely an obstacle. “Will we meet again?” Fabrizio asks on their second chance run-in, to which she replies with absolute confidence, “Fate is on our side.” Of course, this faith rests on flimsy foundations, imbuing material objects with arbitrary meaning in much the same way her friend applies clairvoyant readings to ordinary cards. Ophüls’ formal construction of this character through multiple belief systems is impeccable, eventually rolling them into one when she returns to the shrine of St. Genevieve in the closing minutes of the film, and leaves behind her earrings as an offering to whichever God may be listening.

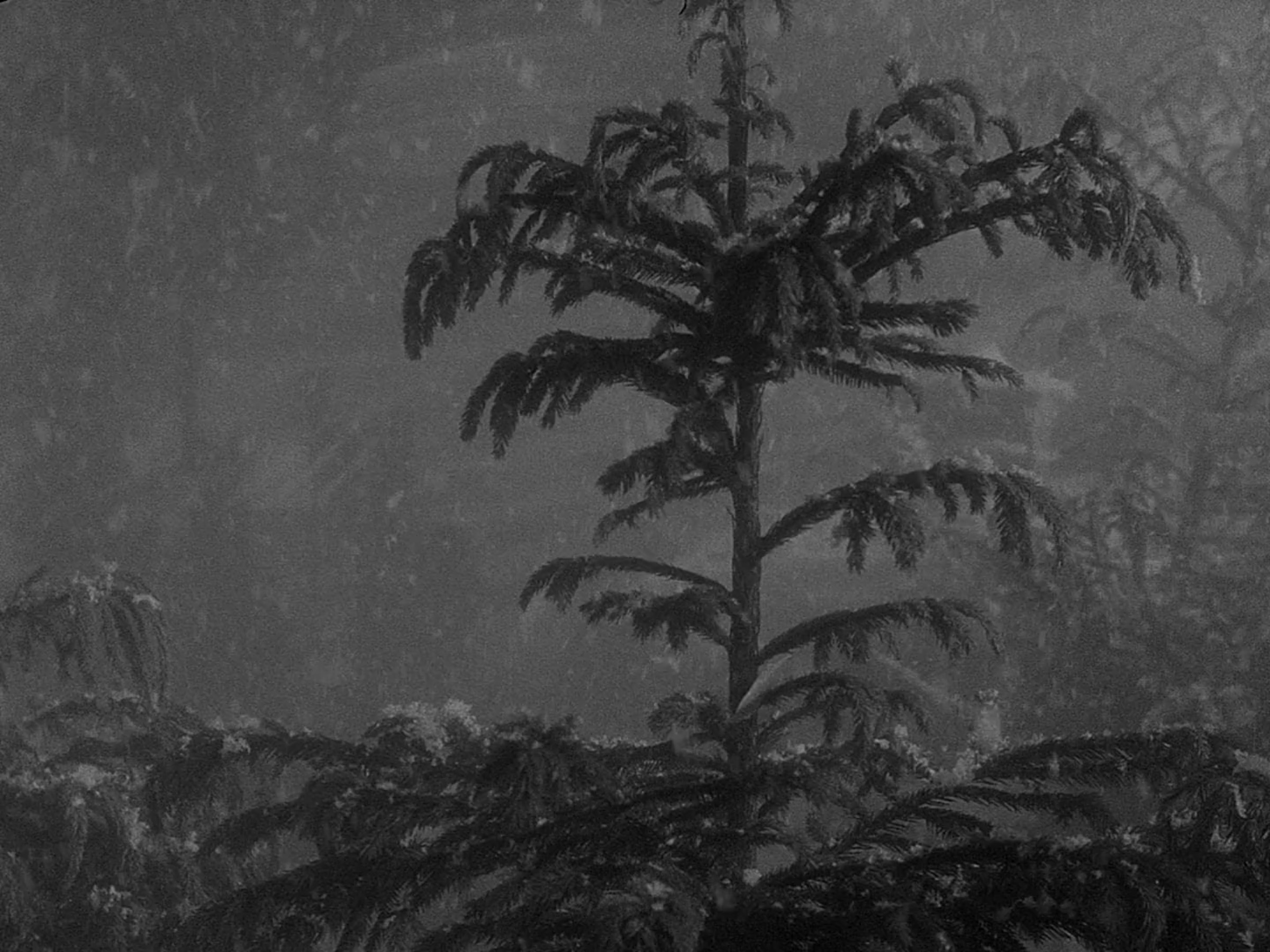

Is it fate then which coincides Fabrizio’s death with her relinquishing of these jewels, or was this merely the random winds of chance delivering a long overdue tragedy to a woman who has never known true heartbreak? Perhaps this vast, erratic cosmos does not care so much for the life of any one individual after all, with the only meaning in it being imprinted by those actively seeking out patterns. Imposing formal structure upon chaos may very well be Ophüls’ job too as a storyteller, but in what is likely the strongest shot of The Earrings of Madame de… he also recognises the human soul’s slow fade into insignificance with romantic poignancy, watching the scattered shreds of a torn-up love letter blow out a train window and join a flurry of snow. Just as it is impossible to find any meaningful configuration in their singular paths, their destinations are similarly unknowable, and yet to follow their journey upon gusts and breezes in this beautiful, fleeting moment is to truly comprehend the inscrutability of life’s unpredictable paths.

The Earrings of Madame de… is streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green