Federico Fellini | 1hr 54min

Italy’s rich tradition of commedia dell’arte is given new life in La Strada’s neorealist update, summoning the stock characters of 16th century theatre into a modern landscape of heartbreaking destitution. Sold by her desperate mother as an assistant to travelling strongman Zampanò, bright-eyed idealist Gelsomina soon finds herself tragically drawn to the sensitivity beneath his toxic abuse, as well as the far more jovial stunt performer, Il Matto – or ‘The Fool’ in English. He is our good-natured Harlequin, often pulling whimsical pranks on the boastful Zampanò who might as well stand in for commedia’s Il Capitano, while offering a gentle wisdom to those who seek his comfort.

Gelsomina is not quite the sad sack that the Pierrot clown was traditionally intended to be, and yet her place as a naïve, disenfranchised victim of society between these two men strongly binds her to that theatrical archetype. Especially when she puts on her striped shirt, baggy overcoat, and face of white makeup to serve as Zampanò’s musical assistant, she transforms entirely into a bumbling comedian not unlike Charlie Chaplin, completing the look with a very familiar bowler hat. Unlike the long-suffering Little Tramp though, there is no romance or comical reversal of fortune waiting for Gelsomina at the end of La Strada. Federico Fellini may hold affection for the clowns of Italian theatre and modern cinema, but so too is he deeply engaged with the hardship that haunted a post-war Europe, extinguishing the joy and laughter that its merry entertainers sought to revive.

There is no doubt to be had that he is the master behind the camera here, astutely blocking his cast within a magnificent depth of field, and whisking them along stretches of dirt track between towns and roadside camps. In front of the camera however, it is Giulietta Masina as Gelsomina who commands our hearts with round, dark eyes that rival Marie Falconetti’s for the most expressive in cinema history, turning her face into an animated canvas of sincere emotion. Whether she is gazing in romantic awe at Il Matto’s fanciful highwire act or raising her brow in miserable surrender to her loneliness, Masina lives in silence, visually conveying the most nuanced of emotions that words could never capture. Even beyond Fellini’s close-ups though, her small stature, androgynous appearance, and bumbling movements reveal a naïve innocence that frequently attracts the company of children. In turn, she offers them comical entertainment, and relishes the simplicity of their playful interactions.

It is a special few people who sense the presence of something truly beautiful in this unassuming woman. The nuns who grant her and Zampanò shelter at their convent see much of their pious lifestyle in Gelsomina’s modesty, and it is clear the admiration goes both ways in the awed reverence she shows for a passing religious procession. Although Il Matto playfully comments on her “funny face” that looks “more like an artichoke” than a woman, he too possesses a powerful belief that everything in the universe carries a greater purpose, and that her humble existence is no exception.

This message inspires Gelsomina with enormous passion, and yet it helplessly falls on deaf ears when she tries to bring it back to Zampanò. He is a brutishly close-minded man, content with performing the same rehearsed trick of breaking chains around his torso with little creativity or variation. It is the small details of their interactions that reveal enormous differences between the two companions, such as her desire to stay longer in one location and watch her planted seeds grow, and his subsequent decision to move onto the next destination. Anything that takes time and patience to cultivate is a frivolous endeavour in his mind, as he refuses to believe in any good greater than his own survival, pleasure, and ego. It is especially the latter which drives him to take violent revenge on Il Matto for getting all three of them fired from the circus, and which leads to the strongman accidentally killing the fool in the process.

True to his neorealist roots as a writer for Roberto Rossellini, Fellini wields his tragedy with a deft hand here, destroying this narrative’s icon of hope much like the cold murder of a pregnant Anna Magnani in Rome, Open City. It is at this moment with Il Matto’s demise that we see something irreparably break inside Gelsomina. “The fool is hurt,” she catatonically repeats, consumed by a maddening cloud of grief that keeps her from performing in Zampanò’s travelling act. Just as her sister who previously served the strongman died while on the road with him, so too is Gelsomina destroyed by his brutality, establishing a pattern of suffering among those women who cycle in and out of his life.

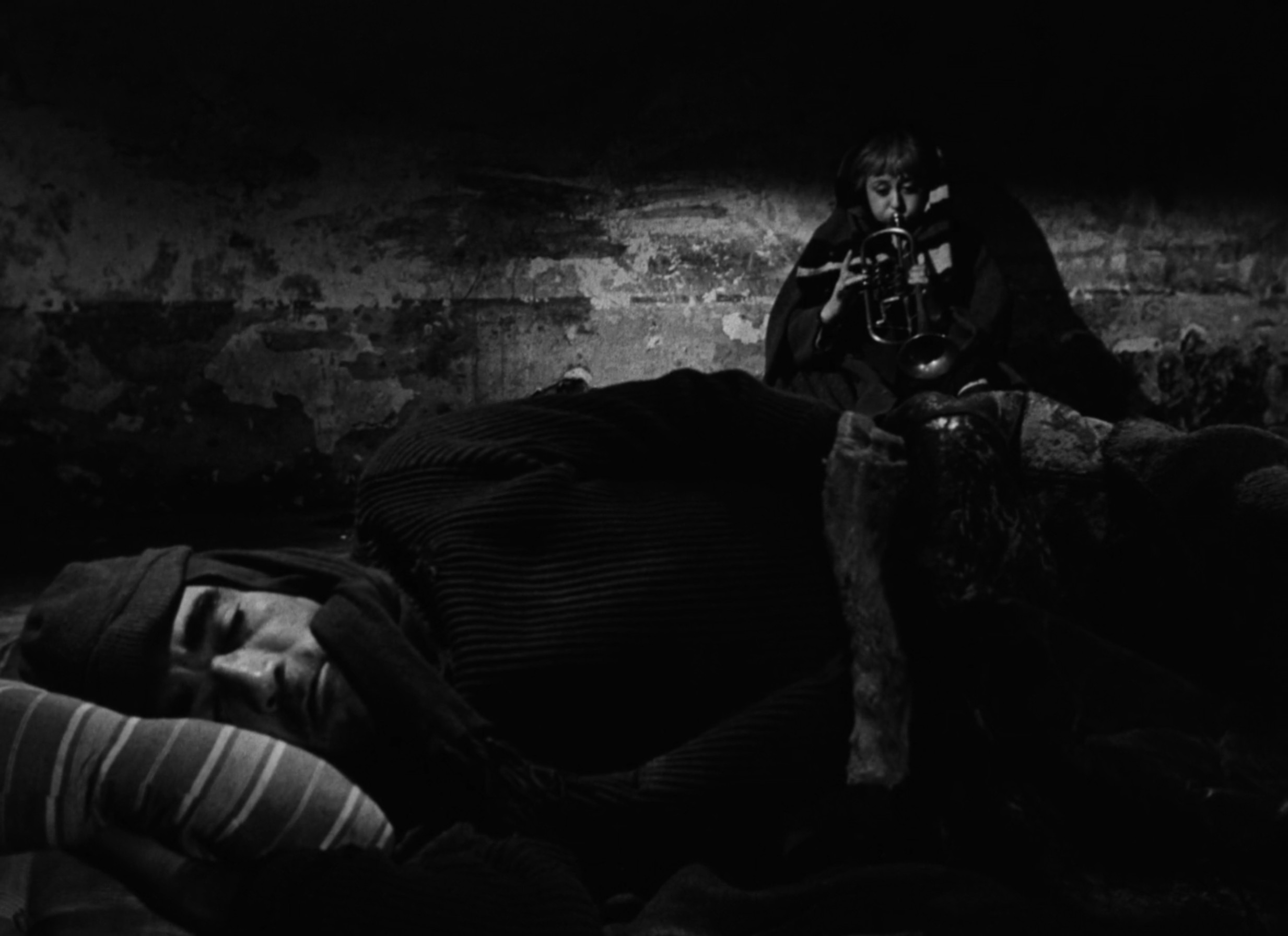

As snow settles on the barren roadside where Zampanò sets up camp with Gelsomina for the last time, he makes up his mind. She is little more than a liability in her current state, no longer of any use to him. While other neorealists were using grand European cities as illustrations of their characters psyches, Fellini’s location shooting in Italy’s countryside simply offers Gelsomina’s abandonment a harsh backdrop of frozen alps and a few crumbling stone walls as she mournfully fades away into the distance.

Still, there is a trace of her spirit that lives on in the wind. A simple musical leitmotif reworked from Antonín Dvořák’s orchestral ‘Serenade for Strings’ resonates a nostalgic longing for brighter days, and becomes an evocative piece of La Strada’s broader form. The refrain carries mystical significance for Gelsomina, fatefully luring her to Il Matto when she first hears it on his violin, and becoming a symbol of their connection as he teaches her how to play it on the trumpet. Even strangers who may be sensitively attuned to delicate artistic expressions finds themselves inexplicably moved by her lonely brass melody, subconsciously realising that they are witnessing the distillation of her soul into music, and soon even Nino Rota starts weaving it into his orchestral score.

Though Gelsomina may have never realised this in life, her motif is the mark she has left on the world, infectiously passing between characters and instruments long after her death. At least Zampanò is still around many years later to hear it sung by a woman hanging up washing in her yard. From her, he learns that Gelsomina survived his abandonment, but was entirely mute by the time this family took her in. Instead, she let this sweet melodic passage become her voice, imparting it as her final gift before passing away.

After all this time, Gelsomina’s undying tune finally touches Zampanò as well, forcing a gutting recognition of the divine innocence he has corrupted. As he drunkenly stumbles through the seaside town, Fellini formally returns to the beach for a third time in La Strada, calling back to their meeting in the film’s very first scene, and another brief stopover where she longingly dreamed of home. He wades through the shallow water, emotionally and spiritually lost, and yet echoes of Gelsomina surround him wherever he goes. Her legacy may not change the course of history, but one cannot help recalling Il Matto’s earlier words of comfort, considering the great purpose that lies within an apparently unremarkable pebble. Even after the worst of La Strada’s tragedies, life persists in the memory of those who are gone – weighing heavily on those who bear their guilty burden, and inspiring those who see the miracle of their mere existence.

La Strada is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and you can purchase the Blu-ray on Amazon.

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green