Grant Singer | 2hr 16min

There is nothing remotely suspicious about the lifestyles of real estate power couple Will and Summer. Nor is there any visible reason why anyone would want to take Summer’s life, leaving her body in a home that they had been showing to potential customers. The two certainly have their enemies, including a few former landowners whose properties they had forcibly bought, but then what wealthy professionals haven’t antagonised a few people on their way up the ladder of success?

Under Grant Singer’s methodical direction, the following investigation carefully unravels a simple murder into a conspiracy that sprawls across the Maine property market, through its illegal drug trade, and into the heart of the police force. Truth is slippery in this moody procedural, as suspects and detectives alike chillingly shed their skins to reveal their true natures, giving metaphoric significance to the title Reptile.

Besides Will’s discovery of Summer’s brutalised corpse in the opening minutes, Singer chooses to filter much of his narrative through the perspective of Detective Tom Nichols, played with haunted cynicism by Benicio del Toro. It isn’t uncommon in his precinct for police officers to casually joke about abusing their power, and even he barely blinks when such remarks are made. Only when he is awarded the Medal of Valor and a large sum of money for inadvertently killing a seemingly guilty suspect that the strings of corruption start to become visible, tempting him to look upward and determine who is in control.

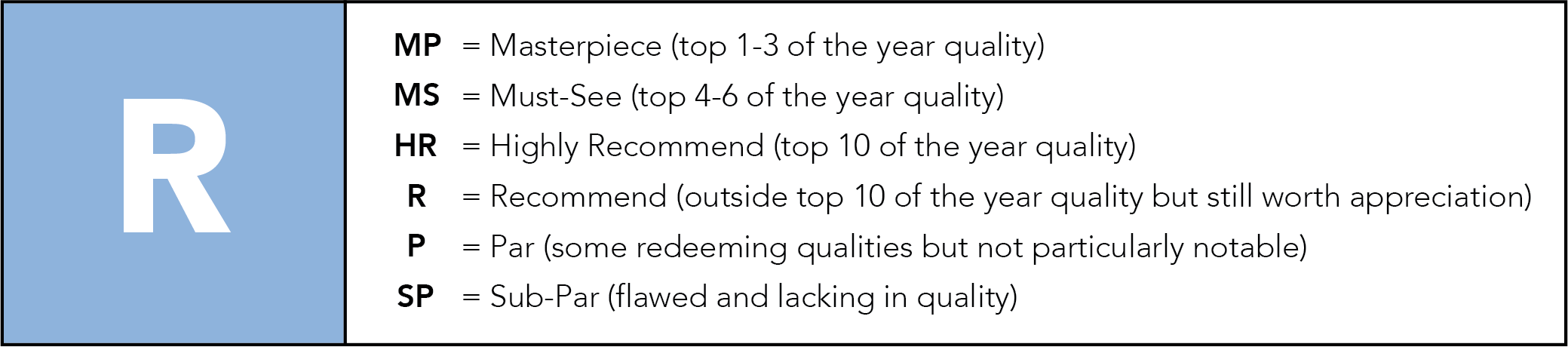

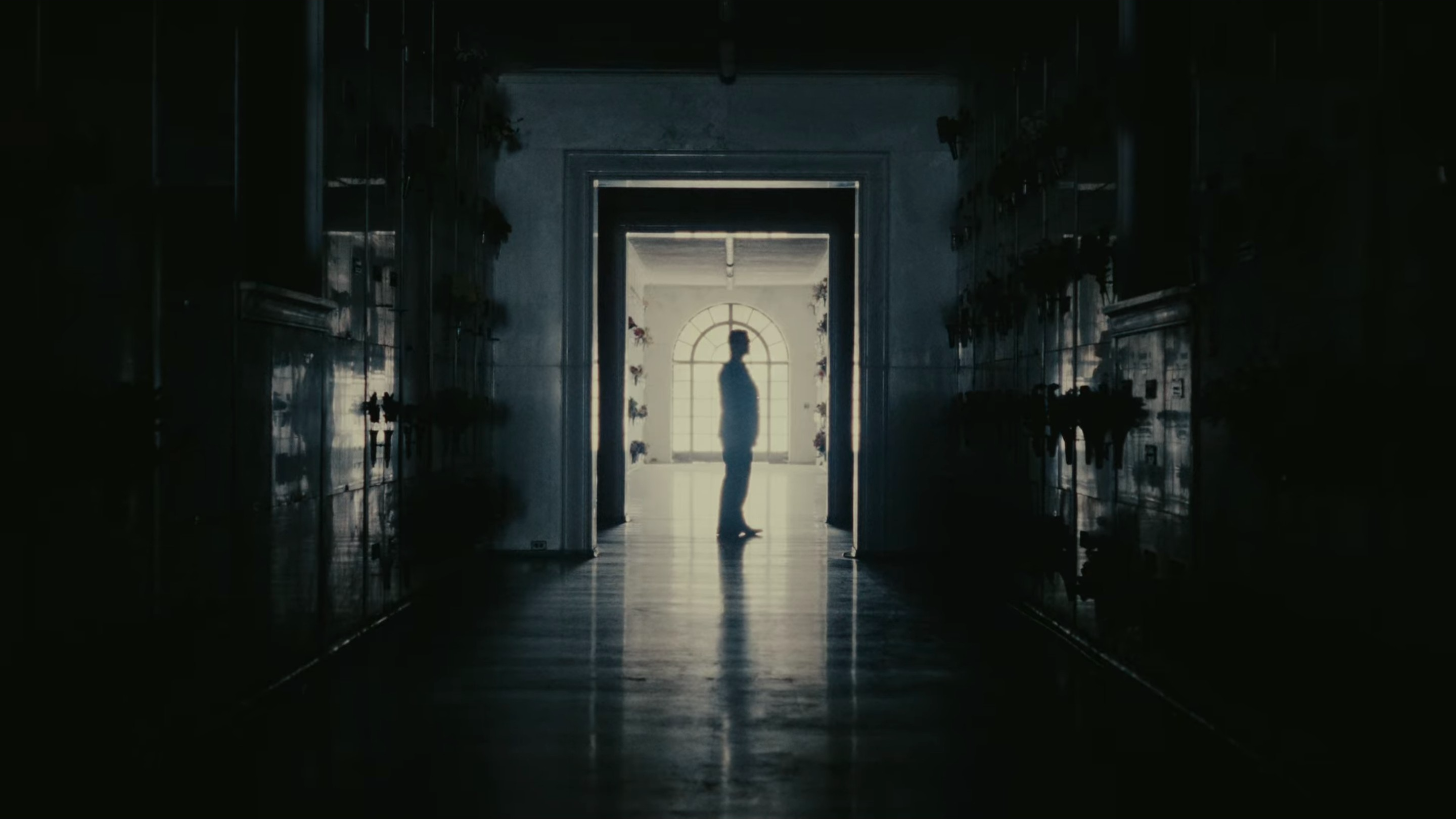

Everywhere we look in Reptile, humanity’s malevolent disregard of life is effectively institutionalised through both private and public enterprises, pointing to a significant narrative influence from David Fincher’s like-minded crime films. The comparison is only reinforced by the echoes of his moody visual style in Singer’s dim yellow lighting, dark silhouettes, and meticulous framing through corridors and doorways, binding grimy downtown bars and upmarket houses together in a shady atmosphere of pervasive mistrust. The camera pans and dollies through these spaces with cautious anticipation too, subtly mounting the tension of Tom’s investigation, and patiently waiting for some cathartic release that we are often denied.

Even by the end of Reptile, many of the puzzle pieces we are handed don’t slot so neatly into the broader picture. Instead, Singer urges a certain level of detective work from the viewer to determine mysteries such as the strand of blonde hair found at the crime scene, which apparently comes from a wig, and the guilt of Summer’s ex-husband Sam whose semen was found in her body. The ambiguity that surrounds the case makes it all too easy to suspect the scorned, lower-class people who Will and Summer have manipulated, and yet it is difficult to ignore the chilling aloofness of those whose souls we assume to be as spotless as their reputations. Like some cold-blooded creature of deceit, anyone who can afford a front of respectability in Reptile also has the ability to emotionally detach from their malicious actions, giving us very good reason to question the motives of anyone privileged enough to have plenty to lose.

Reptile is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Great review. I hadn’t even thought about the Fincher connection, despite being a big fan. Really enjoyed Reptile

Glad to hear it, it’s been fascinating seeing how many newer filmmakers have been influenced by Fincher.

It really has. The man is a legend, although wasn’t hugely keen on The Killer but loved Mindhunter

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green