Jonathan Glazer | 1hr 46min

The great evil that takes centre stage in The Zone of Interest is not often seen alone in historical records. Being married to Auschwitz’s longest-serving commandant, Hedwig’s name is virtually always attached to her husband’s, Rudolph Höss. Perhaps rightly so too. After all, wasn’t the great horror of the Holocaust perpetrated by the highest Nazi authorities, more than the families who never once stepped foot inside a concentration camp? It is not as if Hedwig Höss had any power of her own to halt the momentum of Hitler’s Master Plan, and so where is the harm in enjoying her position of privilege attained through her husband’s line of work?

Still, there is a chillingly blasé attitude here that is evident early in the film when she dons a fur coat from a pile of prisoners’ belongings, tries on the lipstick she finds in the pocket, and vainly admires herself in the mirror. If we are to judge evil based on one’s own moral conscience rather than the tangible impact of their actions, then the self-centred, apathetic woman that Jonathan Glazer depicts in The Zone of Interest may harbour an even darker soul than those who perpetrate the horror themselves. It quite evidently takes a special sort of inhuman cruelty to live in such close proximity to largescale genocide, profit off its spoils, and continue each day as if thousands of people weren’t being routinely murdered just beyond the garden wall.

By the time Rudolph is offered a new job and Hedwig is given an opportunity to move her family elsewhere, it is impossible to excuse her anymore. It isn’t that she is ignorant to the atrocities, nor that she is reluctantly trapped in uncomfortable circumstances. The self-dubbed “Queen of Auschwitz” lovesher home and garden with a vile passion, and will do anything to hold onto this luxurious lifestyle without a shred of care for its appalling foundations.

Purely in terms of genre, The Zone of Interest’s historical fiction couldn’t be further from the science-fiction premise of Glazer’s previous film Under the Skin, and yet the two make for fascinating companion pieces in the realm of sinister, minimalist cinema. If Under the Skin finds the vulnerable humanity in a monster, then The Zone of Interest exposes the monstrosity that resides in a seemingly mundane human, all while Glazer keep us at a chilling distance from both.

Long, static shots especially dominate the aesthetic of the latter, dispassionately setting the camera back at high angles that occasionally lifts into distorted birds-eye views, but more often letting us observe scenes of domestic life bound by that vast, grey wall persistently standing in the background. It serves its purpose well as a physical boundary for the concentration camp, and yet from the other side it fails to completely conceal the terrible truth betrayed by the guard towers, barbed wire, smokestacks, and trains peeking over the top. In sheer contrast, the flowers and vegetables that Hedwig proudly nurtures in her backyard are ironically thriving only a few metres from Auschwitz’s gas chambers, forming a lush, twisted image of Eden that she calls her “garden paradise.”

It is often in scenes set around this visual disparity where the most compelling character work is accomplished, denying Glazer’s characters the sympathy of close-ups, and forcibly associating them with Auschwitz through wide shots. Rudolph may try to block it out when he lights a cigarette and turns his back to the fiery smoke pouring from the gas chamber chimneys behind him, but the camera stoically captures it all, denying him anywhere to hide in the frame. Even when Glazer’s compositions aren’t so visually arresting, the formal rigour of this icy detachment is powerful, evoking the severe, psychological cinema of Stanley Kubrick and Michael Haneke. When it comes to the interiors of the Höss household though, the flat colours, crisp depth of field, and use of background doorways as frames makes Roy Andersson an even stronger comparison, seeing Glazer deploy a similarly dry, dark humour with discerning judgement to underscore the setting’s sheer incongruency.

The few times the camera is taken off its tripod, it travels in steady parallel motions, but otherwise it is through the rhythmic repetition of familiar shots that we track the banal routines of the Höss family. On this level, Glazer’s poetic visual beats and editing cadences reveal Yasujirō Ozu to be another unexpected influence, even if The Zone of Interest never quite touches the heights of the Japanese director’s masterpieces. The few times he diverges from his rigid formal structure with misplaced negative exposure shots and a single fade to red also weakens the similarities somewhat, and yet these flaws are little more than minor distractions from an otherwise relentless portrait of historic fascism, loaded with magnificently subtle worldbuilding.

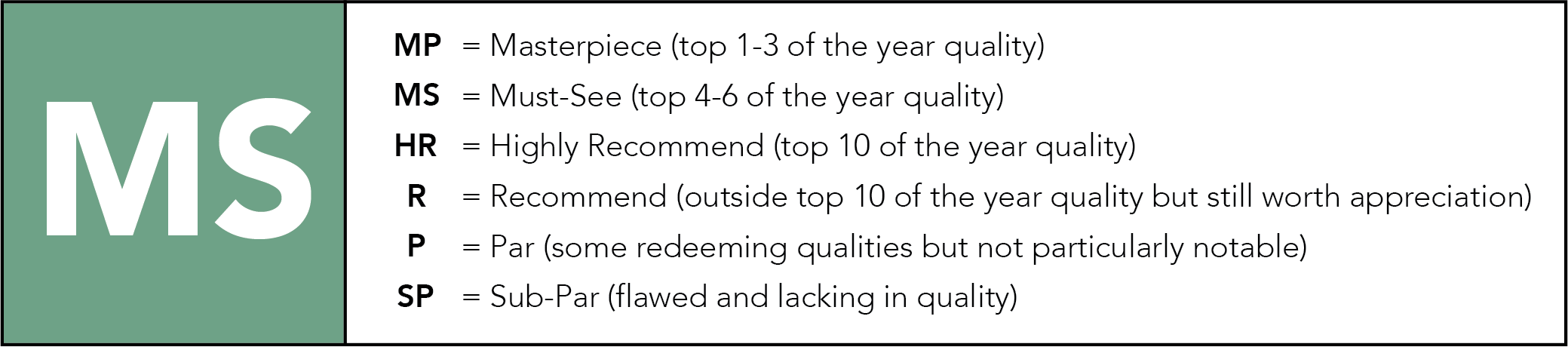

Because as a disquieting immersion into the outskirts of Auschwitz, The Zone of Interest is just as concerned with the stifled remnants of horror lingering in the haunting sound design as it is with its visual details. Distant gunshots interrupt Hedwig’s quiet life, but she gives them as little attention as does the shouting guards, crying babies, and tortured screams that fill the air. Mica Levi’s sparse score intermittently lets out deep, guttural groans that could very well come from some demonic engine, and it too blends eerily well in with the mechanical grinding of machinery that can be heard whenever a new train of prisoners arrives, or when the gas chambers are set to work. The only time that Glazer amplifies this horrendous soundscape is also the only instance that his camera cuts to a close-up, letting us deduce from the audio alone that we have crossed the threshold into Auschwitz, and are currently standing in the middle of the concentration camp.

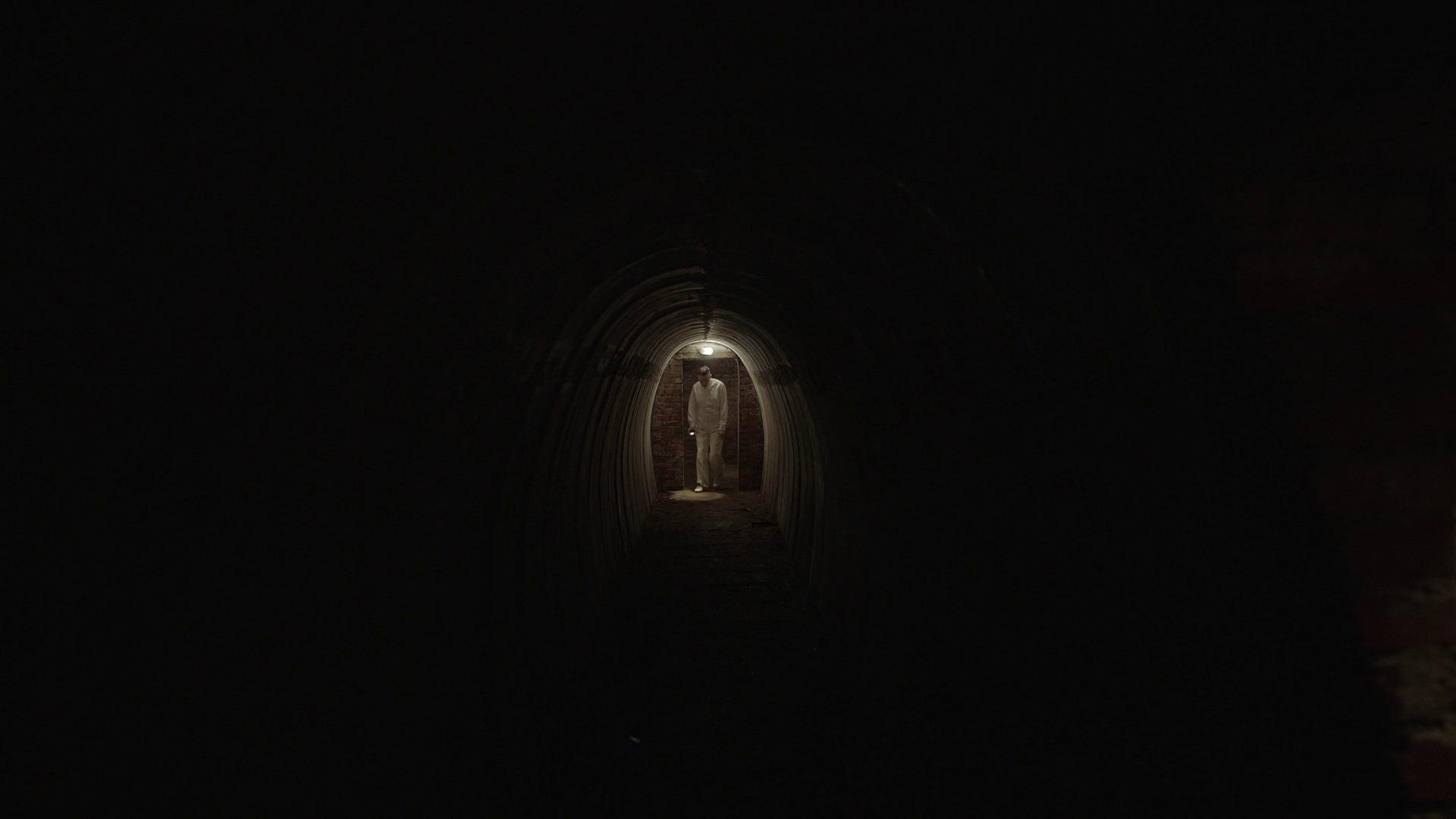

For the most part though, this sound design is quietly hypnotic, lulling us into the same state of helpless submission that each character must face and which exposes the true nature of their soul. Nowhere is this reckoning illustrated so vividly as when Hedwig’s mother visits the villa and tries to sleep, only to be confronted with blazes of fire from the gas chambers lighting up her bedroom. All she can do to shut it out is draw the curtains, but not even that can silence the hellish blasts that continue to keep her up. In the middle of this sequence, Glazer meanwhile cuts to Hedwig, who couldn’t be sleeping more soundly.

The profound, emotional unrest that moves her mother to leave without warning the following day is not one the Queen of Auschwitz would ever understand. In fact, Hedwig alone may be the only significant character in The Zone of Interest to never even display the tiniest shred of guilt buried deep in her mind. At least her husband Rudolph is forced to gaze upon Nazi Germany’s vile operations every day when he goes to work, thus grasping on some instinctual level the inhuman barbarity that he is perpetrating – not that this absolves him. His hypocrisy is extremely evident when he evacuates his children from a river upon discovering human remains floating by, attempting to shield them from the consequences of his own actions, though his psychological compartmentalisation is never clearer than in the very final minutes of Glazer’s film.

Rudolph initially receives the news that his name is to be given to a key operation in Auschwitz’s success with excitement, most of all because of what it means for their family’s security and comfort. Still, as he departs his office and begins his journey down several flights of stairs, some visceral disgust erupts from within. He pauses, heaves, and dry retches, before descending another storey – only to uncontrollably give into that primal urge again.

At first, the following flashforward to images of present-day Auschwitz appears formally unjustified, like some clumsy attempt to strip the film’s message of its poetry. Cleaners sweep empty gas chambers and sanitise the furnaces, while the camera observes the mountains of shoes preserved behind windows as historical artefacts. A touch of Alain Resnais’ documentary Night and Fog can be felt here too as Glazer’s camera solemnly beholds the lifeless remains of this great historical tragedy, but then just as we are expecting the film to end, it cuts back to Rudolph.

Call it a premonition, or simply a sudden, unexplainable feeling that his name will forever be attached to one of humanity’s greatest injustices, but whatever shame Rudolph feels in this moment doesn’t halt his descent into darkness. This is how fascism survives, Glazer gravely laments. Not through the destruction wrought by torture, murder, and genocide, but through the passive denial of reality by those who reap its rewards and swallow their nauseating self-hatred as they go. As for those like Hedwig Höss who betray no such remorse for their exploitative privilege, and who are even given the benefit of Glazer’s judicious camera to peel back the layers around their empty soul – perhaps they stand alone at the top as the greatest evil of all.

The Zone of Interest is currently playing in theatres.

Great page – even without including some of my favourite shots here (the meeting near the end). In general when putting together a page do you focus on images that add context to your own words or showing off the best the film has to offer…. or a mix?

I mostly aim for the best images, and then try to match them up with my writing. Sometimes I’ll include a striking image just for the sake of it, even if it isn’t strictly relevant. But in this case I was limited to screenshots from the trailer, which is unfortunately the case with many new releases. I did go looking for more memorable shots, but I don’t think the trailer really showed them off.

Have you ever used FilmGrab? They have a page full of shots for Zone of Interest:

https://film-grab.com/2024/03/11/the-zone-of-interest/

I use filmgrab all the time, but it looks like that page was put up only a day ago, which was after I put my own together haha. I may update it at some point with images from there.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Why did you find the negative image scenes misplaced? I thought they were stunningly powerful – and I’ve seen other reviews where the reviewers didn’t understand what they represented. What did you think they were supposed to represent, and why did you think they were a mistake to show in the film?

I suppose it must be a failing if so many people missed the meaning behind those scenes, but I’d love to know why you felt that and put it in your review.

I saw what it was depicting as a small rebellion in the middle of incredible horror. My issue is more to do with how it breaks from the film’s broader patterns at play, particularly since this film is so rigorously built on its patterns. I see that it is trying to strike a contrast, especially aesthetically, but I would have liked to have seen it woven in a little more evenly. From what I can remember (though correct me if I’m wrong), it comes up twice – perhaps if it was a more consistent motif this idea would have been developed more thoroughly.

Ah, great. Yes, I had seen a review that thought it was some abstract dream sequence, and I was shocked they didnt understand it was the daughter in a moment of real humanity trying to feed the prisoners. Her fear and desparation is palpable in the scene, and heightened by the night-vision goggles and soundtrack, which I thought was very effective.

I think it is a common feature in Glazer’s films to put a visual break in his films (think the underworld in Under the Skin or the rabbit pacing in the grave in Sexy Beast), so I was almost expecting it. Note that it occurs in both cases with Hoss reading stories over the soundtrack – him trying to give his girls lessons in bedtime stories, while the daughter in the NVG scenes is the only moral character in the family. I feel like the style of the scenes is important – in such stark visual and sonic contrast with the rest of the family because her actions are so opposite, so contrasting with the inhuman action of her parents and cowardice of her grandmother.

That’s how I was seeing it anyway. Thanks for the reply.

I like your reading of it, my thoughts on it could always change on future viewings as well.

Imo, the look of this film is way too clean and neat.

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Cinematographers of the Last Decade – Scene by Green