Howard Hawks | 1hr 42min

From the moment that the scatter-brained Susan throws David’s golf game into chaos at their very first encounter in Bringing Up Baby, unruly forces of nature seem to conspire against the perfectly ordered life he has built for himself. A leopard called Baby sent from Brazil unexpectedly falls into their care, wreaking havoc on his plans to complete a giant Brontosaurus skeleton at his museum, and marry his fiancée Miss Swallow the next day. A troublesome dog named George interferes too, running off with the final bone needed for his project, and a second, dangerously untamed leopard complicates the ordeal even further when it is freed from a local circus.

These mischievous creatures represent more than just the breakdown of structure in David’s life though, wearing away at his patience until he surrenders to the mayhem. Howard Hawks’ animalistic subtext is ridden with sexual innuendo at every turn, comically undercutting the seriousness of David’s mounting stress with reminders of his vulnerability and repressed, primal desire.

With the Production Code’s censorship at its peak in 1938, Hawks and his screenwriters could have never been so explicit with their gags even if they wanted to, yet the underhanded subtlety of their perpetual double entendres speaks even more acutely to David and Susan’s simmering romance than any brazen statement of their attraction. Besides, David’s just not that sort of man to speak so plainly of such personal matters. Only when he is forced to beg Susan to return his balls, goes searching for his “precious” bone, and becomes a surrogate parent to Baby is he able to admit to his innate animalistic impulses.

If Baby the leopard effectively becomes David’s child with Susan, driving them mad with frustration, then that giant dinosaur skeleton which he is working on with Miss Swallow is theirs, and she virtually says as much herself. “This will be our child,” she proclaims, gesturing at this dry, dead beast. “I see our marriage purely as a dedication to your work.” Not even she is saved from Hawks’ sexual innuendos, with him poking fun at the connotations of her suggestive name, and humorously implying the sterility of their relationship as David ponders where his new bone goes.

“You tried in the tail yesterday and it didn’t fit.”

With jokes this sly being thrown out at such a breakneck pace by Hawks’ talented ensemble, we are often left catching up on several punchlines at a time. This propulsive narrative power and madcap energy isn’t atypical of 1930s screwball comedies, but Bringing Up Baby reaches near-perfection in the hands of a genre master like Hawks, orchestrating an amusingly tense dynamic between his actors that lands each comic beat with razor sharp timing. Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde no doubt deserve credit for penning one of Hollywood’s finest comedies too, but at the same time this is just the springboard for two career-defining performances – Katharine Hepburn taking control of scenes with her rhythmic dialogue and clipped intonations, and a sarcastic Cary Grant nervously stammering through the confusion.

“Now it isn’t that I don’t like you Susan, because after all in moments of quiet I’m strangely drawn to you. But, well, there haven’t been any quiet moments.”

With actors, writers, and director working at the top of their game, Bringing Up Baby is about as flawless as any piece of cinema can get with such little dedication to any distinct aesthetic. Hawks’ physical gags may be hilariously inventive, at one point seeing Grant awkwardly hide the back of Hepburn’s ripped gown by trailing behind her a little too closely, but this is not the sort of visual comedy innovated by Buster Keaton which relied heavily on framing and composition. Almost the entirety of the comedy here is driven by the eccentric screwball antics, leading a pair of opposites towards a more fulfilling romantic union than either of them previously knew existed, as well as the erotic subtext that lies just beneath its surface.

Hawks formally signposts the disruptive transgression of this relationship virtually all the way through the film too, with Susan implicating David in a few minor crimes at the start, and later stopping to note the unlikely friendship that forms between Baby the leopard and George the dog. Most prominent of all though is the gender subversion that Hawks wields such a deft hand over, dressing the low-voiced Hepburn in traditionally masculine outfits and positioning her as the more dominant figure, while Grant is forced to dress in a fluffy negligee upon realising his clothes have been stolen. On one level, his improvisation when he suddenly meets Susan’s Aunt Elizabeth while wearing this outfit is simply an exasperated resignation to the ludicrousness of the situation without even trying to explain himself, though on another he is sardonically pushing the boundaries of his own apparent queerness even further.

Elizabeth: You look perfectly idiotic in those clothes.

David: These aren’t my clothes.

Elizabeth: Well, where are your clothes?

David: I’ve lost my clothes!

Elizabeth: But why are you wearing these clothes?

David: Because I just went GAY all of a sudden!

It’s too bad for him that this Aunt Elizabeth also happens to be the multimillionaire who has offered a large donation to his museum, should he prove to be a suitable enough candidate. The rest of the evening doesn’t exactly prove her first impressions wrong either, especially with Susan still drawing him into her hijinks. Mistakenly believing he is a zoologist, and later lying to her aunt that he is a big-game hunter, she is constantly landing David in awkward positions that assume he possesses some dominance over the animal kingdom, only to expose his total ineptness. No matter how hard he tries to coax Baby off rooftops with hilariously desperate renditions of ‘I Can’t Give You Anything But Love’, he is not a man who controls nature, but is tormented by its unpredictability and lack of order.

In short, Susan embodies all of David’s most embarrassing weaknesses, continuing to radiate her aura of chaos out into the lives of strangers and drawing them to a jailhouse in Hawks’ climactic comedic set piece. The farce which binds them, Miss Swallow, Aunt Elizabeth, her lawyer, her housemaid, a big-game hunter, a circus crew, and a pair of daft policemen together within a series of misunderstandings only continues to disintegrate the bureaucratic structures which hold society together, until everyone is cut down to the same humiliating level.

As Susan unwittingly leads a dangerous leopard right into the middle of this crowd and sends them climbing the prison cell bars, it is clear that no one is safe around her, but perhaps David is the only one who can see the joy in such maddening volatility. Once the dust has settled, he barely seems fazed when Miss Swallow curtly breaks off their engagement back at his museum, and even when Susan accidentally sends his prized brontosaurus skeleton tumbling to the ground, he quickly moves past the loss of his life’s work. After all, that dinosaur was the child of a relationship he now realises was uncompromisingly rigid and exceedingly inauthentic. The dead belongs to the past, Hawks symbolically asserts, while life in all its impulsive uncertainties should be embraced, delivering an amusingly peculiar logic in the romantic union of two incongruent yet totally compatible opposites.

Bringing Up Baby is not currently available to stream in Australia.

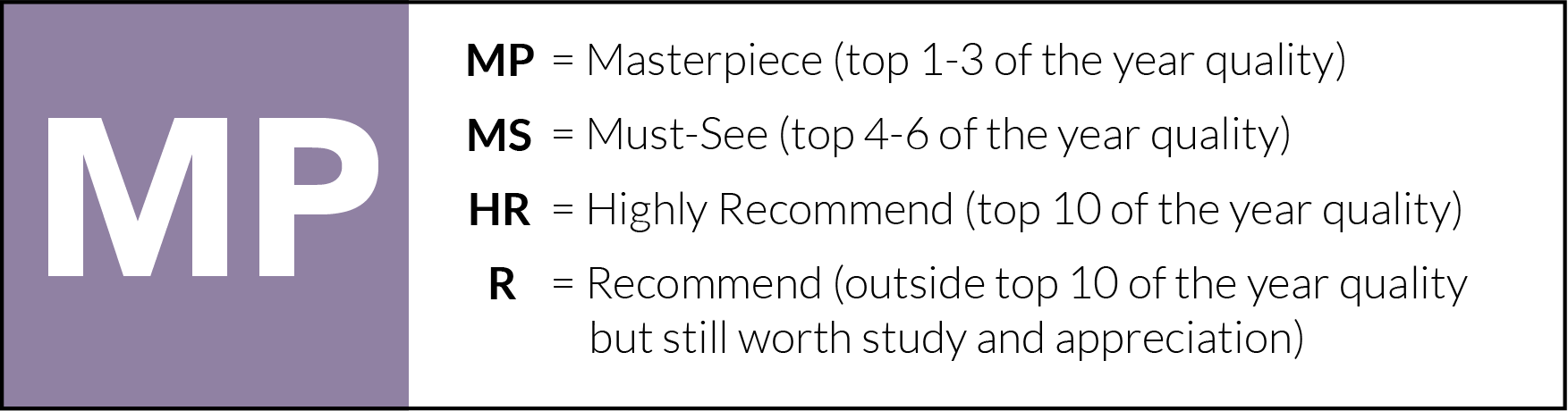

I want to ask what exactly makes it a masterpiece? Is it a masterpiece of formal, screenplay brilliance just like Annie Hall.

Its screenplay and performances are tremendous, but I think it is the form that just pushes it over the line. It’s not as experimental (or strong) as Annie Hall, but impressive nonetheless.