Wes Anderson | 1hr 45min

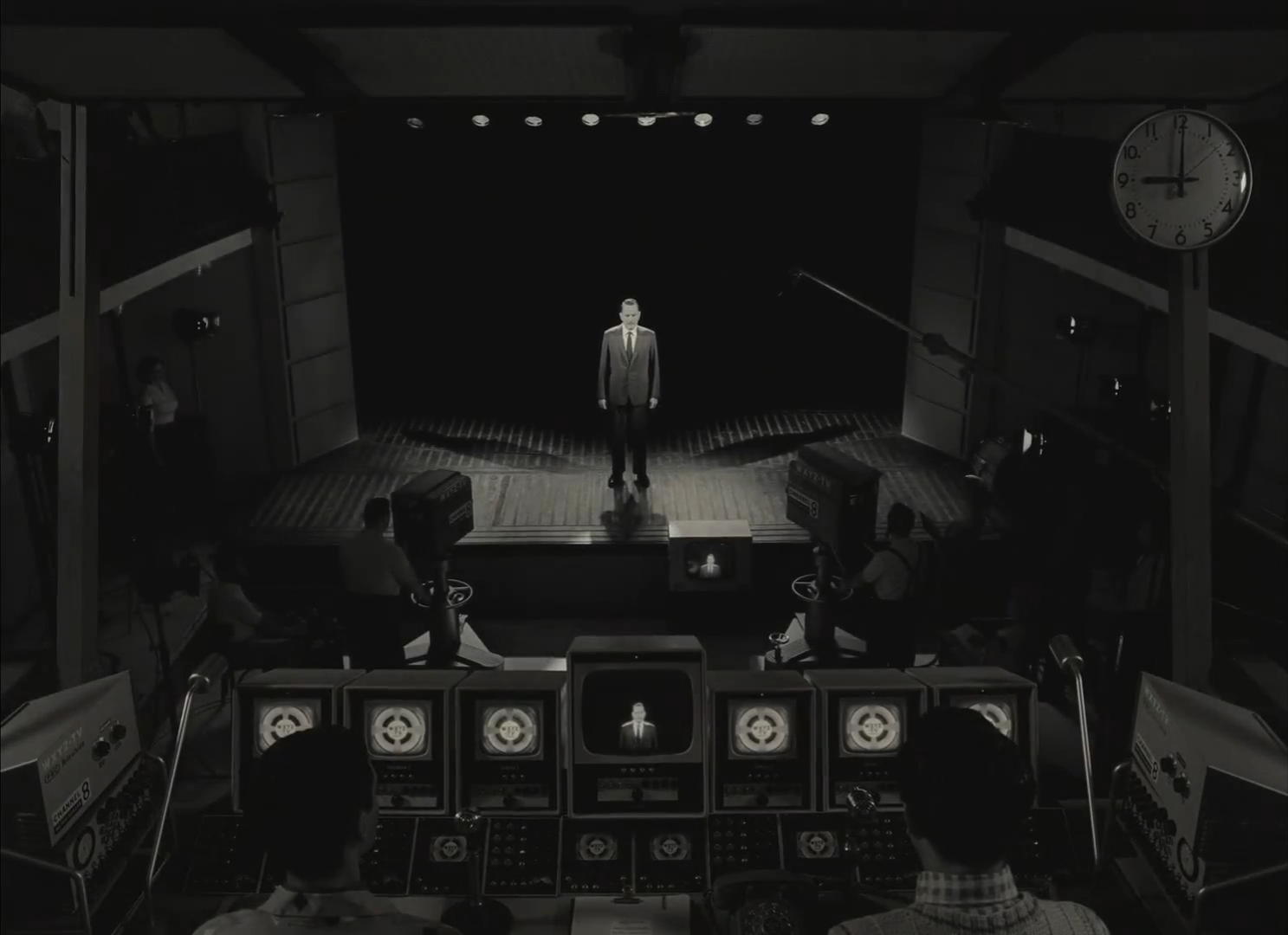

Buried beneath the deadpan line readings and self-aware framing devices of Asteroid City, there is a quiet, repressed grief, fighting to reach the surface. The story of the youth astronomy convention visited by extra-terrestrials is only the innermost layer of its narrative, framed within a fictional play which in turn is being featured on an exclusive behind-the-scenes 1950s television program. This nesting doll structure isn’t unusual for Wes Anderson, whose cinematic storytelling has always relished mimicking traditional forms of media, but the boundaries between his fictional layers here are far looser and more perplexing than we have seen before.

Augie Steenbeck is the widowed father of four who has been waiting for this family road trip to tell his children of their mother’s passing three weeks ago, while Jones Hall is the actor who plays him. Co-starring next to him is world-weary actress Mercedes Ford playing the equally jaded actress Midge Campbell, who has similarly been drawn to Asteroid City for her daughter’s participation in the astronomy convention. It takes us a few seconds to recognise when either actor breaks character, remarking on the greasepaint used for a black eye or an unexpected commitment to burning one’s hand on a hot griddle. In fact, the lines between performers and their fictional identities become more obscure the deeper we get, as Anderson gradually blurs them until they essentially become one.

There is an underlying logic to these fourth wall breaks in the metacontext of the television production, though they also heavily suggest a personal dissociation that lets these characters step back and question their own actions. “Why does Augie burn his hand on the Quicky-Griddle? I still don’t understand the play,” Jones questions at the chaotic climax of Asteroid City, before heading backstage to chat with the director.

“He’s such a wounded guy. I feel like my heart is getting broken, my own personal heart, every night.”

“Good.”

“Do I just keep doing it?”

“Yes.”

“Without knowing anything?”

“Yes.”

The exchange almost sounds like a man speaking to his own conscience, spurring him on to conquer the inhibitions that keep him from understanding the logic of the universe, as well as his own soul. It doesn’t matter if can’t intellectually comprehend the deep grief of the man he is playing, he is told. “You just keep telling the story. You’re doing him right.”

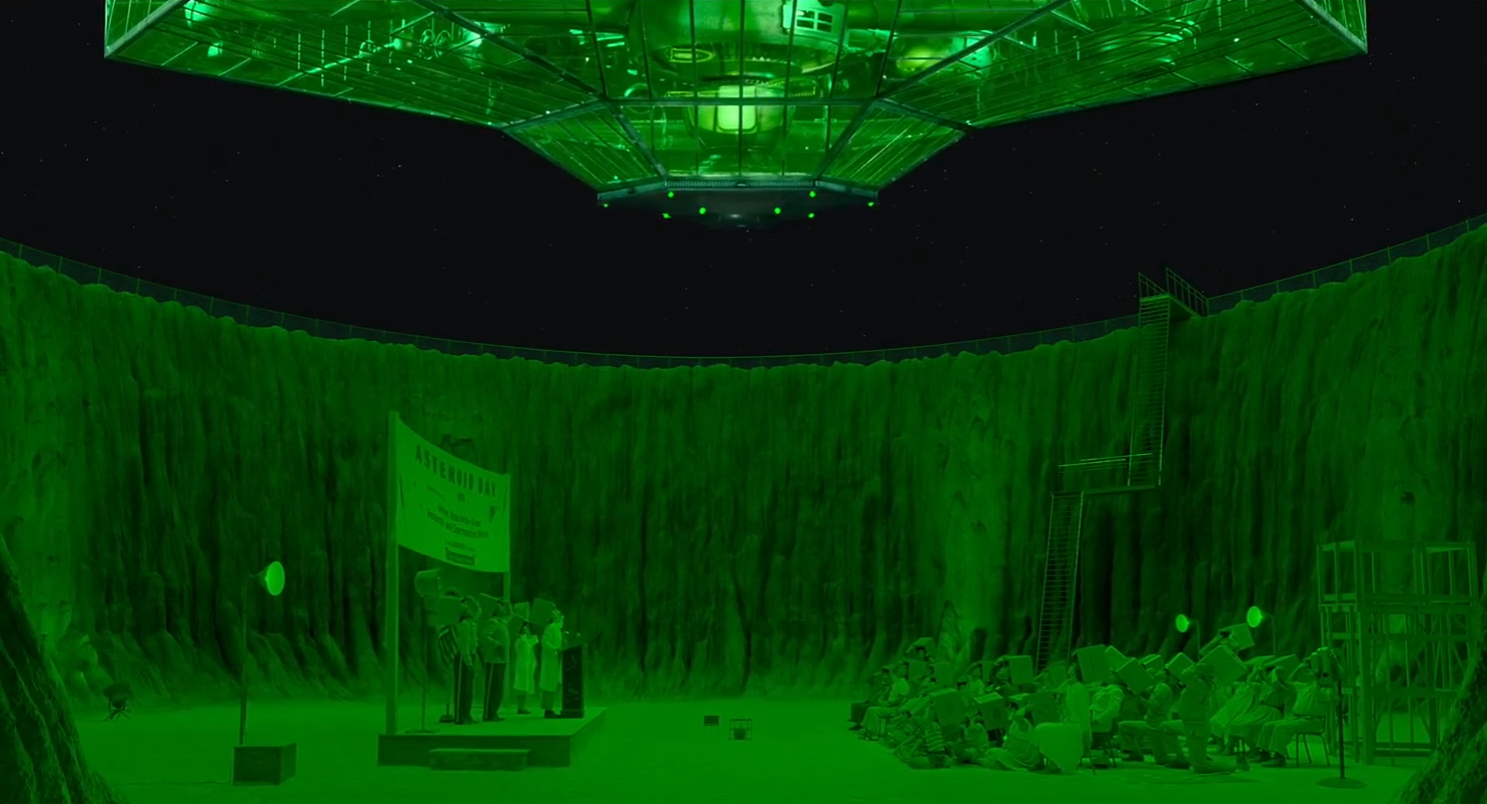

Anderson’s trademark self-awareness may be reaching a peak here with the metanarrative of Asteroid City. It is almost impossible to escape the confines of theatrical or televised media here, through which authentic emotions are filtered until we reach enough of a distance to consider their purpose, thereby letting us emerge out the other side as more conscious beings. That is certainly at least the experience that Jones undergoes as he sees parts of himself in Augie, and it is at the core of the enigmatic mantra chanted by the play’s cast in one surreal, unsettling dream sequence.

“You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.”

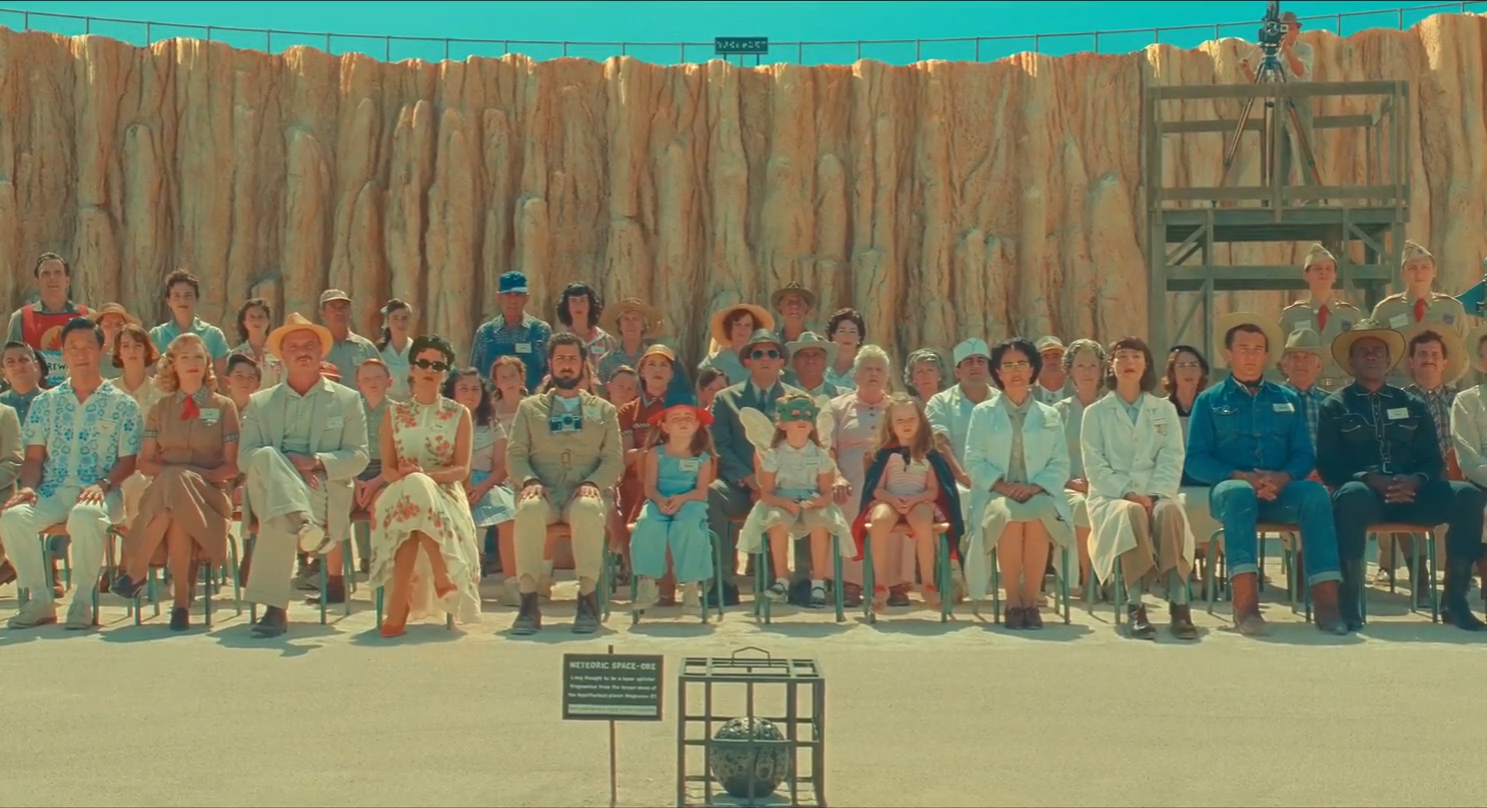

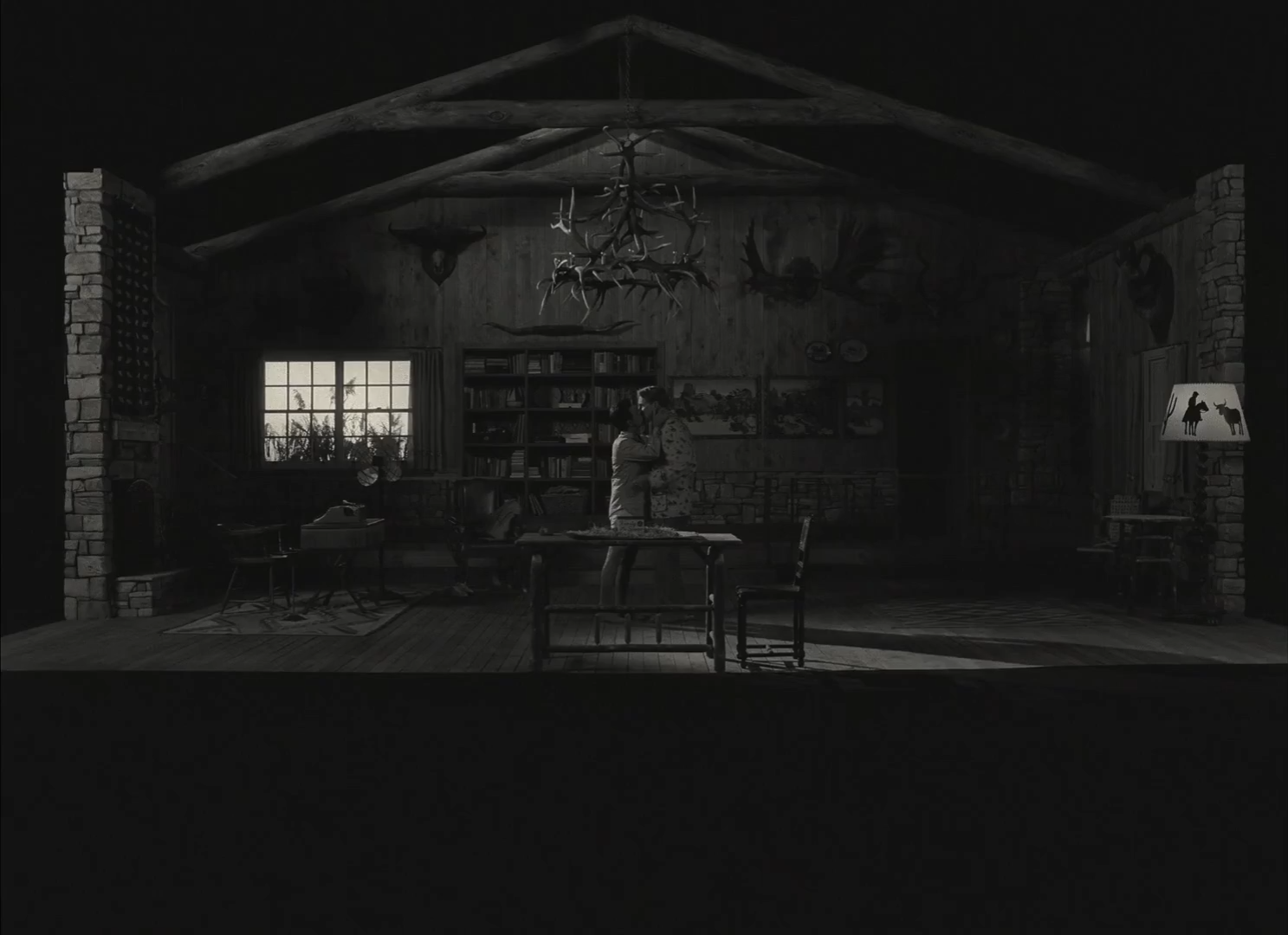

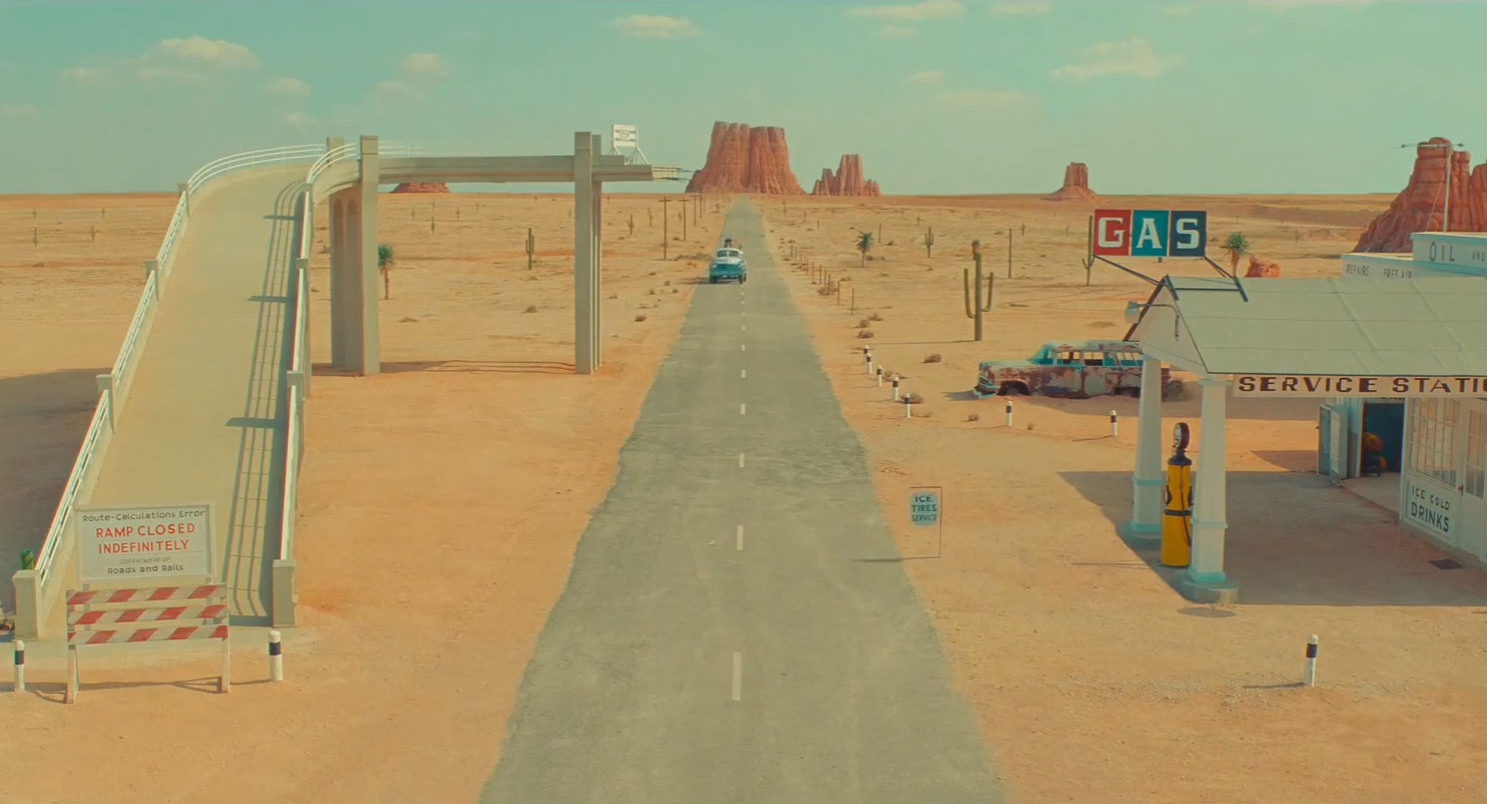

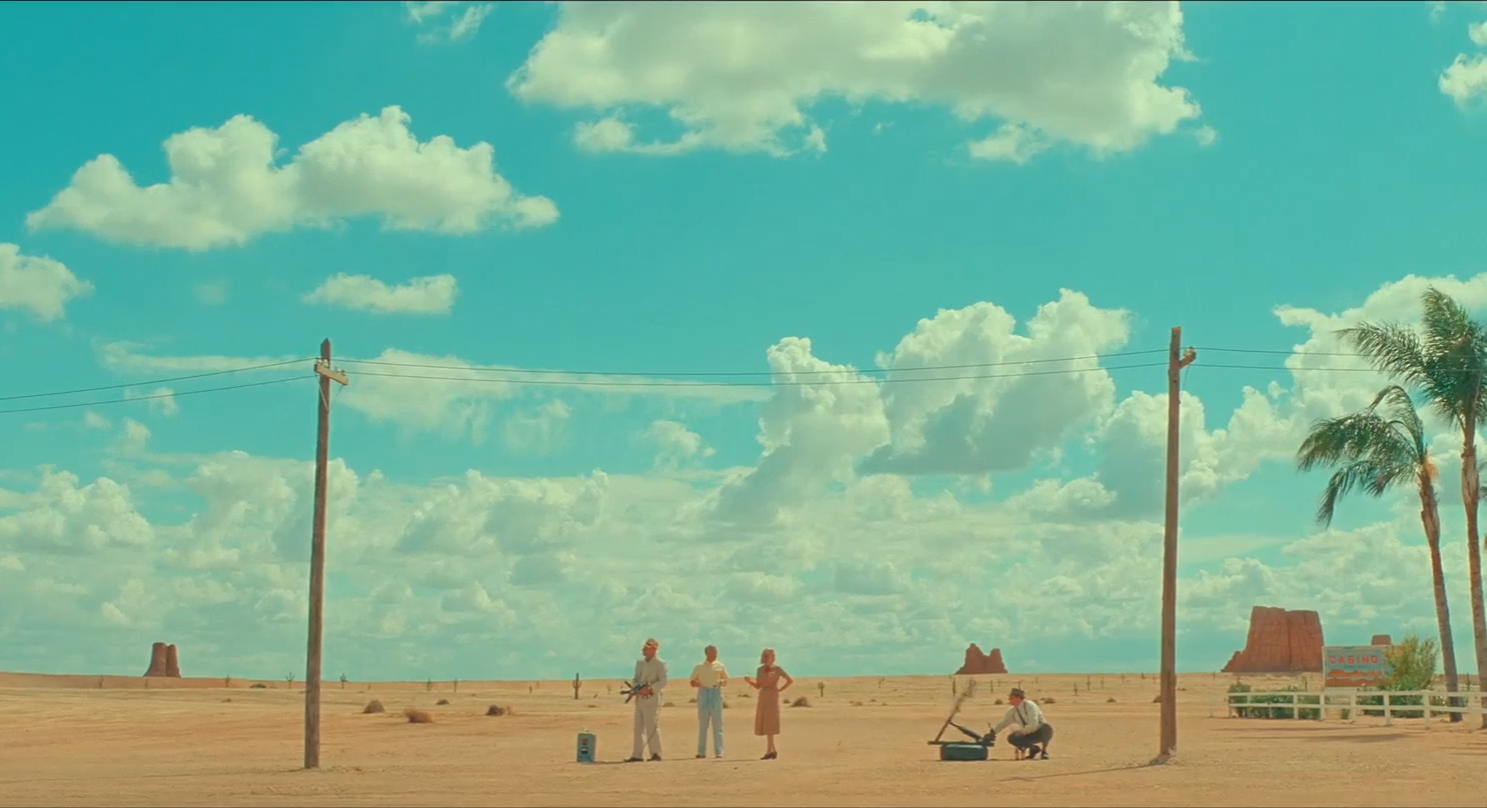

Indeed, much of Asteroid City feels as if we are watching one of Anderson’s own dreams of eccentric characters and quaint visual designs, only to be woken up every now and again to recognise its artifice. The fictional play escapes into a world entirely distinct from the boxy aspect ratio and black-and-white cinematography of the television segments, even while Anderson’s crisp depth of field, symmetrical framing, and rigorous blocking are carried across both. In fact, it even transcends the limits of any Broadway theatre as well, unfolding across expansive desert sets saturated with faded pastel blues and yellows. The seams where the floor meets the matte paintings in the background are conspicuous, as is the theatrically curated design of those train and building miniatures that populate its dry, rural landscape.

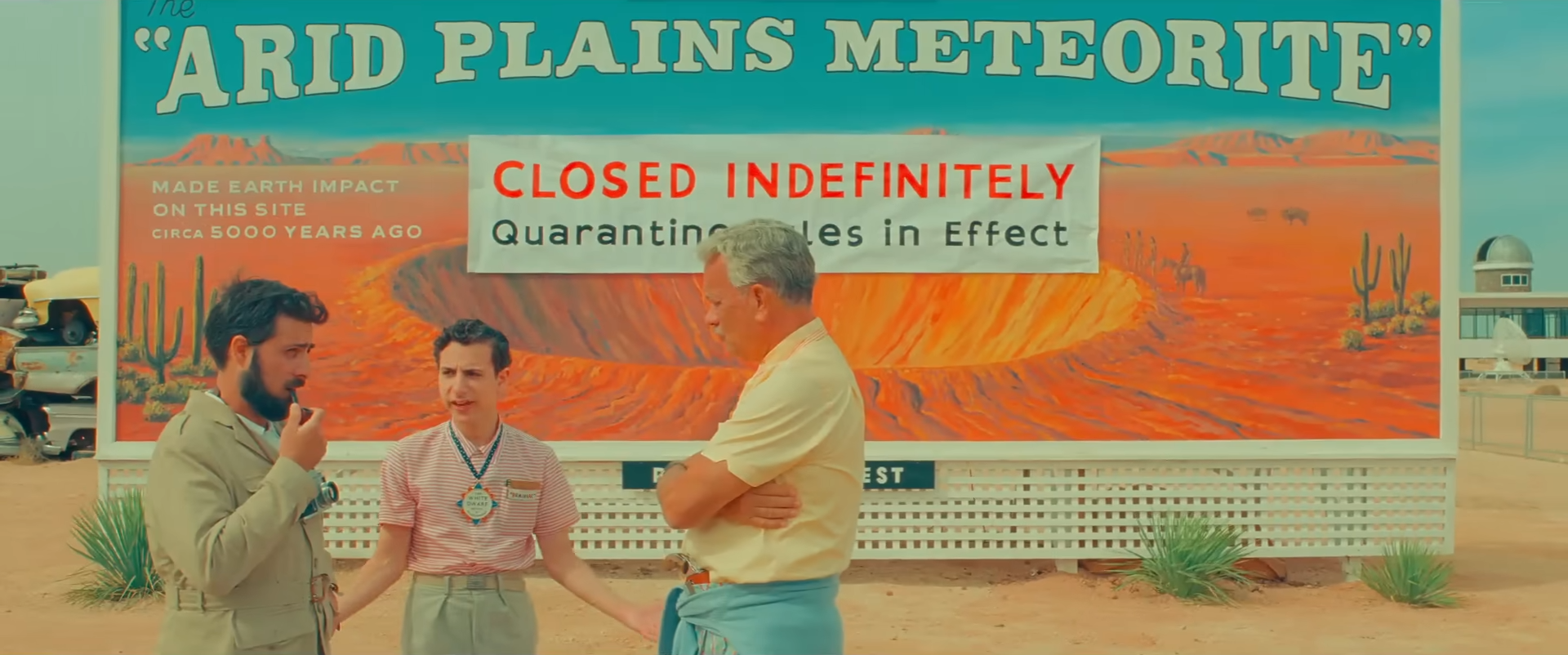

Anderson’s camerawork matches the geometric precision of his mise-en-scène as well, travelling in parallel tracking shots, tilts, and pans whenever he breaks free of his static tableaux. These devices make up the entirety of the long take which first introduces us to Asteroid City before the convention guests arrive, noting its sparse features – a diner, a motel, a half-constructed overpass, and of course the giant crater which gives the town its lofty name. In the distance, atomic bomb tests occasionally disrupt the flat horizon, though these are of little concern to the locals who mainly consist of small business owners and astronomers. They are proud of their town’s small claim to fame, and don’t hesitate in capitalising on their national media coverage when they are unexpectedly visited by aliens.

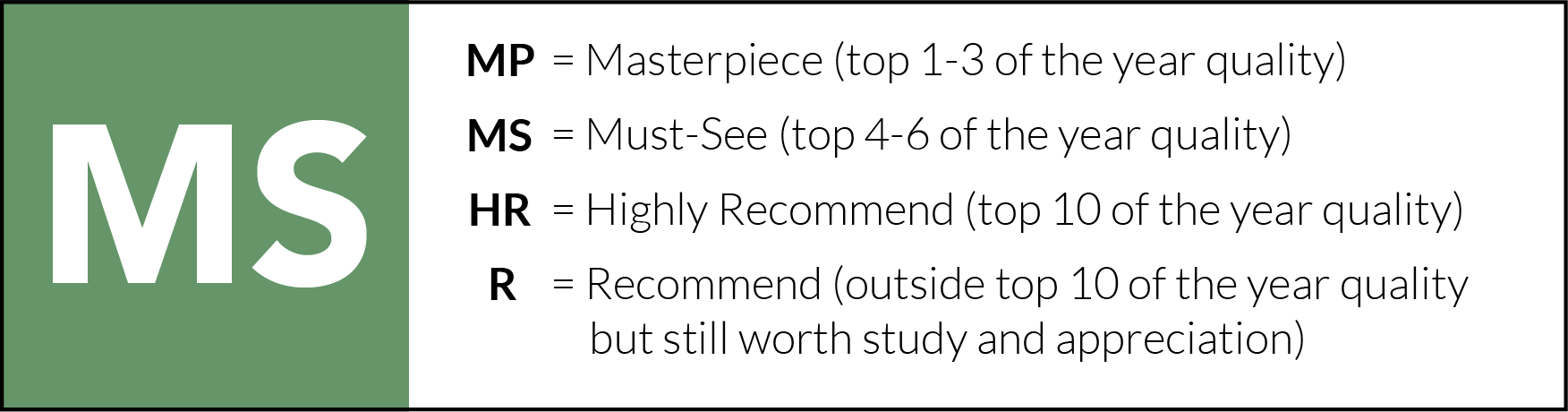

From the long shots of the town’s 1950s architecture to the throwaway visual gag of the real estate vending machine, there is a thorough dedication to world building all through Anderson’s mise-en-scène, but it is also in his sprawling cast that he develops the rustic southwestern culture of the community. Steve Carrell, Matt Dillon, and Tilda Swinton are among a handful of residents with small-town mannerisms, while Tom Hanks, Liv Schreiber, and Jeffrey Wright fill in the roles of its curious outsiders. Another layer out, we find Edward Norton, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Margot Robbie, and Jeff Goldblum backstage at the theatre, and Bryan Cranston hosting the television program itself, though the most substantial roles are reserved for those two esteemed actors playing Augie and Midge.

Within this enormous ensemble of A-list actors, Jason Schwartzman and Scarlett Johansson are the centre upon which Anderson’s deadpan drama pivots. Beneath their mannered affects is a mutual fatigue and sorrow, shared in conversations between their neighbouring cabins. The small windows in the side of each hem them into claustrophobic frames, effectively isolating them in their respective worlds, but even so there is a tenderness to their connection that promises a chance to break free of their emotional constraints. If only they had more time for them to explore this further.

It is hard not to see the parallels Anderson is drawing to the global pandemic lockdowns with the arrival of an alien that sends the entire Junior Stargazers convention into quarantine. He is not so much interested in what this “bewildering and dazzling celestial mystery”represents though than the repercussions it leaves in its wake, breaking up the milieu of these characters’ lives and offering them the time to re-examine their relationships. In effect, this is another layer of dreaming which cuts them off from reality, yet which opens new possibilities as romances are forged, school students befriend a travelling cowboy band, and Tom Hanks’ wealthy retiree finds a new respect for his son-in-law. Sleep is not a state of passive inactivity, Anderson posits, but rather renews our connection to the world when we eventually return to it.

This is crucial to Jones’ and Mercedes’ development as they sink into the fictional roles of Augie and Midge, only to find mirrored versions of themselves. Mercedes’ disillusionment with the industry is shown early in Asteroid City when she almost quits the play right before opening night, while the source of Jones’ heartache isn’t revealed until the end, though both emerge in their characters as Augie helps Midge to rehearse for an upcoming project. “Use your grief,” she instructs him after a lacklustre performance, and not only do we see Augie’s pain surface in the following line delivery, but Jones’ as well. In an even more obscure fourth wall break that could be spoken by either Mercedes or Midge, they finally realise what binds all four of them together.

“I think I see how I see us. I mean I think I know now what I realise we are. Two catastrophically wounded people who don’t express the depths of their pain because we don’t want to. That’s our connection. Do you agree?”

When Jones randomly encounters the actress who played Augie’s deceased wife before her scene was cut, he finds an even sweeter catharsis to his emotional turmoil, as they recall the lines that they might have shared together in a dream scene. After leaving one stage show, she has simply taken on a part in another, though there is no sorrow to be found in that departure – just new beginnings.

In Anderson’s grand metaphor for life and death, everyone is constantly performing roles that they may not fully understand how to play, whether it be as a father, a widower, or professional actor. These are not lies, but rather parts through which humans may understand their truest selves, should they fully submit to these alternate identities and emotionally reconcile them with each other. It is fitting too that a filmmaker so often accused of inauthenticity should find the sincerity in such artifice, and attach such a great spiritual significance to it. Through the union of dreams and reality in Asteroid City, Anderson crafts a cinematic model of this self-realisation, and reverberates a sweet, formal harmony across its sprawling layers of truth.

Asteroid City is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2020s Decade (so far) – Scene by Green

We watched an agonizing hour of this exquistely BORING show!!!!! How anyone thought it was great is crazy. If you think it seems bad in the first ten minutes, here’s a warning- It doesn’t get any better.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green