Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 31min

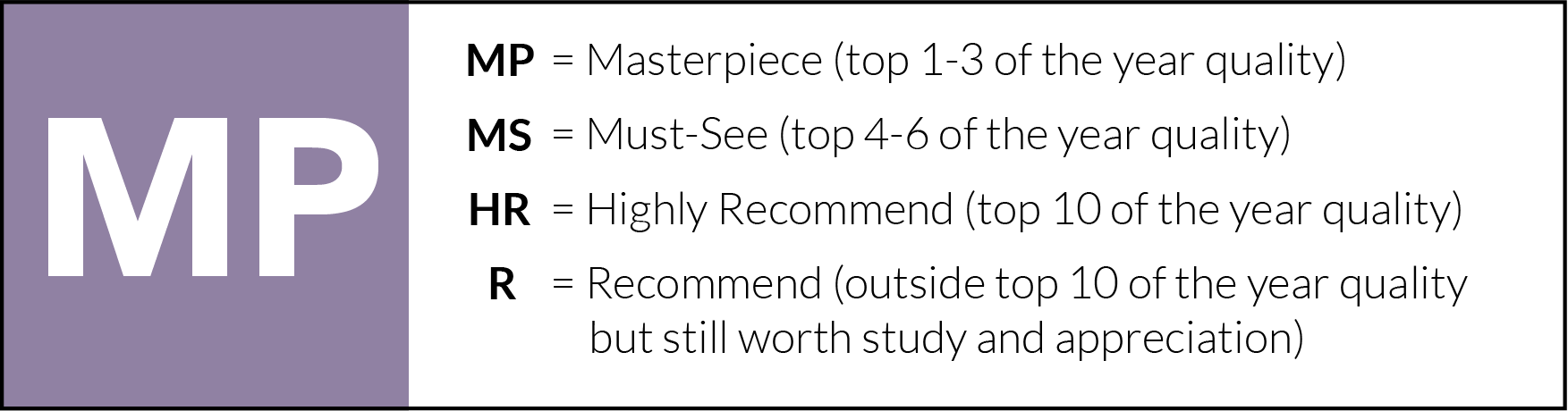

Merely describing the vibrant colour palette that consumes the four women of Cries and Whispers as red wouldn’t quite do its richness justice. Its carpets, furniture, and drapes are shaded a deep, vibrant crimson, bleeding an arresting sensuality throughout the 19th-century Swedish manor which most of its inhabitants are incapable of expressing themselves. This is the colour of the human soul, Ingmar Bergman rationalises in his screenplay, but it also represents blood and passion, drawing this family household to the edge of its sanity where an almost fantastical dream state takes over.

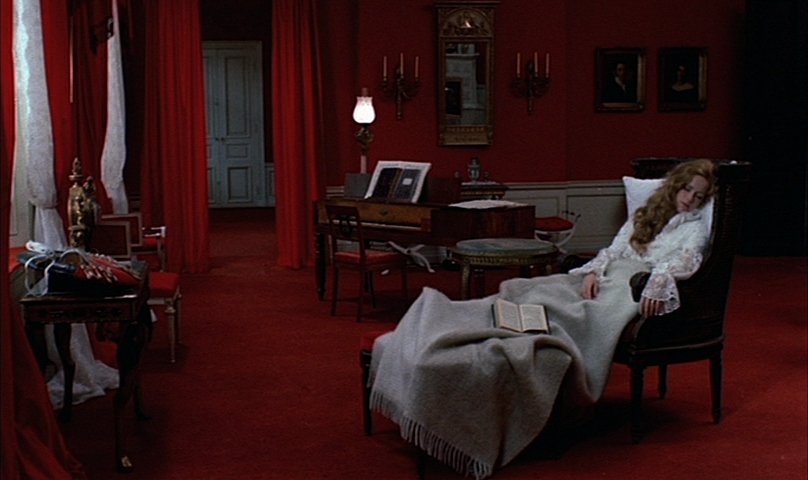

The white and black tones which puncture Bergman’s neatly curated interiors offer a stylistic counterpoint to these saturated reds, though they too confine characters within a rigorous dichotomy, presenting purity and life on one side while grief and death beckon from the other. Neither Karin’s cold severity nor Maria’s flighty temperament can offer the solace that their dying sister Agnes needs in her final days, and so the spiritual strength that their housemaid Anna finds to escape this scarlet membrane brings a redemptive grace to her mortal suffering.

The Madonna and Christ allegory which Bergman draws so delicately in his imagery is especially apparent in this relationship between Anna and Agnes, seeing the latter abandoned by all her loved ones save for a single mother figure. Through her cries and screams, she expresses the pain that others would much rather stifle in a “web of lies,” while finding maternal nourishment in Anna’s warm embrace. It isn’t hard to see where this nurturing compassion comes from either – early on we find Anna praying for her deceased daughter, simultaneously mourning her lost innocence and demonstrating an unconditional faith in God. As she bears her breast and reads from a storybook, Bergman nestles her face against Agnes’ in a tightly framed composition of profound intimacy, filling in the void that each feel in their respective losses of a biological mother and child.

It is a wonder that this love abides in a household of such glacial friction, distilled so hauntingly in one dream sequence following Agnes’ death. Both she and Anna’s daughter are effectively resurrected here with Christlike parallels, as it is the sound of a young girl’s crying which leads Anna through the mansion’s red corridors to the bedroom where Agnes lies. Outside, Karin and Maria stand frozen. Agnes’ face is barely seen as she speaks to each of them, disembodying her voice as she invites them inside. “I want nothing to do with your death,” Karin cruelly asserts before exiting, while Maria’s show of affection crumbles into fear the moment her sister reaches out and grasps her hand. Only Anna is there to nurse Agnes’ frail body through the pain, as Bergman arranges them in an extraordinary tableau evoking the Pietà – the theological icon of Mary cradling Christ’s body after his descent from the cross. This is also one of the few shots in Cries and Whispers which sees Bergman relinquish his crimson palette to clean, white tones, bathing both women in a sea of spiritual purity.

Even beyond this explicitly surreal sequence, there is an atmosphere of otherworldly detachment that persists in the narrative’s quiet, languid flow, echoing Bergman’s previous film The Silence. “I hear only the wind and the ticking of clocks,” Anna remarks at one point, reflecting on the subtle, dialogue-free sound design, representing the “wind” as Agnes’ rattling gasps for air. Together, these rhythmically embody what editor Ken Dancyger describes as “the continuity of time and life,” and merge with formal cutaways to swinging pendulums and moving minute hands. The mystical pull of mortality is felt on every level of Bergman’s direction, luring us into the uneasy mind of each sister and empathising with their emotional disconnection.

“I sometimes wander through this childhood home of ours, where everything is both strange and familiar… and I feel like I’m in a dream, and some event of great importance lies in store for us.”

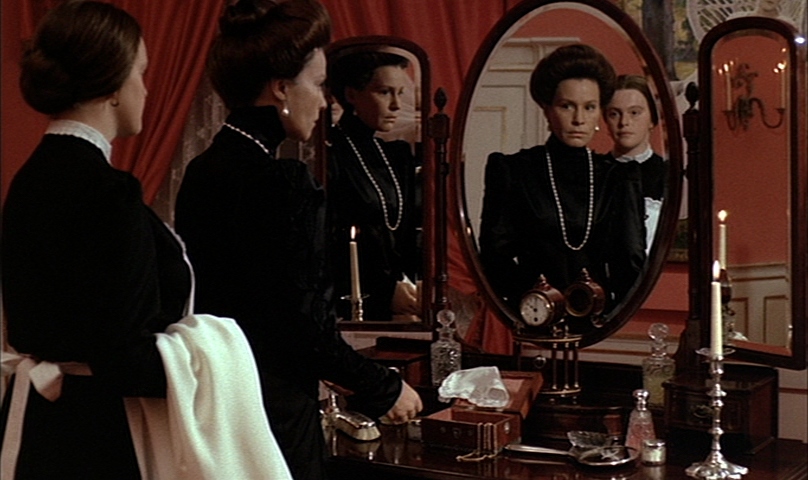

Key to Bergman’s construction of this reverie are those scarlet fades which elliptically bridge one scene to the next, lifting us outside the passage of time altogether. They also formally mark our escapes into his characters’ minds, pairing with close-ups of each woman’s face half-obscured in shadow and drenching them in his bloodred hue, before entering the deeper levels of their subconscious. While Anna’s thoughts manifests as a dream, Agnes, Karin, and Maria’s backstories emerge in flashbacks, blurring fantasy and memories in a magical realist style presaging Fanny and Alexander.

This is also where Ingrid Thulin and Liv Ullmann excel in further developing the prickly weaknesses of their characters, seeing both distance themselves from their husbands to violent results. While Maria’s affair with a visiting doctor drives Joakim to feebly attempt suicide via seppuku, Karin turns a shard of shattered glass on herself in a self-mutilating display of hatred. After cutting her genitals in front of Fredrik, she smears the blood across her face with a contemptuous smile, simultaneously absorbing the red palette of her surroundings and destroying any means of sexual connection.

In the present, both continue to live with the consequences of their selfishness and hatred. Karin recoils at the slightest touch of affection, paradoxically rejecting the kindness of her sister even as she craves it, and Maria is still a slave to her own fickle desire for pleasure and attention. When the doctor returns, her attempt to rekindle their affair meets nothing more than a cold description of how her appearance has festered with her apathy, and of course Bergman plays the entire monologue out in a single close-up studying every detail of Ullmann’s silent reaction.

“Look in the mirror. You’re beautiful. Perhaps even more than when we were together. But you’ve changed and I want you to see how. Now your eyes cast quick, calculating, side glances. You used to look ahead straightforwardly, openly, without disguise. Your mouth has a slightly hungry, dissatisfied expression. It used to be so soft. Your complexion is pale now. You wear makeup. Your fine, wide brow has four lines above each eye now. You can’t see them in this light, but you can in the bright of day. You know what caused those lines? Indifference. And this fine contour from your ear to your chin is no longer so finely drawn – the result of too much comfort and laziness. And there, by the bridge of your nose. Why do you sneer so often? You see that? You sneer too often. You see it? And look under your eyes. The sharp, scarcely noticeable wrinkles from your boredom and impatience.”

When we consider how favoured Maria was by her mother above her sisters, the psychological roots of her shallow vanity and strained family relations become evident. It is a clever formal touch from Bergman to double cast Ullmann as the mother as well in Agnes’ childhood flashbacks, suggesting that the two characters she plays are not so different, and sensitising us even further to the subjective nature of these sisters’ memories.

Within this ensemble, only Agnes seems to treat these recollections with some self-awareness, so it is fair to reason that this is why her recollections eliminate those dreamy red fades and instead play out with the pensive voiceover of her diary. Though her mother could be a “playfully cruel” paradox at times, Agnes also confesses that she understands her much better with age, empathising with “her boredom, her impatience, her longing, and her loneliness.”

Given how walled off Karin and Maria are from their own spiritual conscience, the redemptive peace that their sister discovers in her suffering is not one that either can grasp at this point in their troubled lives. For Agnes at least, salvation can be found just beyond the red walls of her physical confinement, as Bergman ends Cries and Whispers on a memory that is entirely free of that radiant hue. Only when we look to a happier past can we venture outside this oppressive manor and into bright, sunny gardens, as she walks with her Karin, Maria, and Anna in white dresses. In the triad of tones which form Bergman’s dominant palette, it is that colour which represents grace that lives on in Agnes’ legacy, illustrating her profound gratitude for life.

“Thus, the cries and whispers fall silent,” Bergman’s epitaph reads, drawing spiritual peace from humanity’s emotional and physical anguish. His wrestling with matters of faith has never been so vividly illustrated as it is here in a film that stands among the greatest uses of colour in cinema, untangling the stunted relationships and regretful insecurities of these four women through their surreal, tortured dreams.

Cries and Whispers is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1970s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green