David Lynch | 2hr 4min

At first glance, The Elephant Man does not hold to the definition of Lynchian which the surrealist director set for himself in his debut Eraserhead and would further refine in Blue Velvet. Its biographical narrative follows traditional Hollywood convention far more closely than those obscure, psychological dreams he is famous for, each of which strip back the illusions of modernism to expose uglier truths about humanity’s corruption. When interpreted through that sociological lens though, perhaps The Elephant Man doesn’t fall so far outside David Lynch’s realm of interest after all, as the severely deformed John Merrick simply becomes another device in his arsenal to expose the true essence of our moral being.

Tying this film even closer to his usual dreamlike style is the dark thread of surrealism emerging in a series of nightmarish interludes. Slow-motion close-ups of a rearing elephant and Merrick’s terrified mother are set against dark, smoky backdrops, playing out like a childhood memory distorted by years of shame and terror. John Morris’ tinkling circus score eventually gives way to the creature’s distressed trumpeting, though with the sound design’s constant clanging it could just as well be the whine of an old factory machine. Merrick is dehumanised by many people throughout The Elephant Man, and especially from those who liken him to that enormous, lumbering animal, but the harshest judgement of all comes from his own debased self-image.

Aside from its relatively conventional narrative, the other aspect of this biopic that differs from Lynch’s usual standard is the hope it pulls from such melancholic tragedy. This is not sentimental in the way a 1950s Hollywood treatise on human kindness might be, but it rather walks a finer tonal line through the stagnant gloom of 19th century London, positioning John right at the bottom of a social ladder defined by the era’s dog-eat-dog industrialism. When surgeon Frederick Treves first meets him, Merrick’s only purpose is to serve the cruel ringmaster of a freak show, entertaining and horrifying audiences like the tortured somnambulist of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Lynch continues to evoke Robert Wiene’s expressionistic aesthetic in his design of the carnival as well, matching it to Morris’ deranged circus waltz and continuing to escalate his morbid aesthetic from there.

This is a prime visual achievement for both cinematographer Freddie Francis and production designer Stuart Craig, who under Lynch’s direction craft a monochrome Victorian dystopia with incredible period detail and a rich depth of field. The lighting especially casts its streets in a smothering, smoky haze, and conceals Merrick in shadows up until his uneasy reveal. Lynch’s camera traverses this urban Gothic scenery with an eerie elegance mirrored in Anne V. Coates’ fluid editing, as her dissolves, match cuts, and elliptical fades to black generate a dreaminess seeking to penetrate Merrick’s emotional defences.

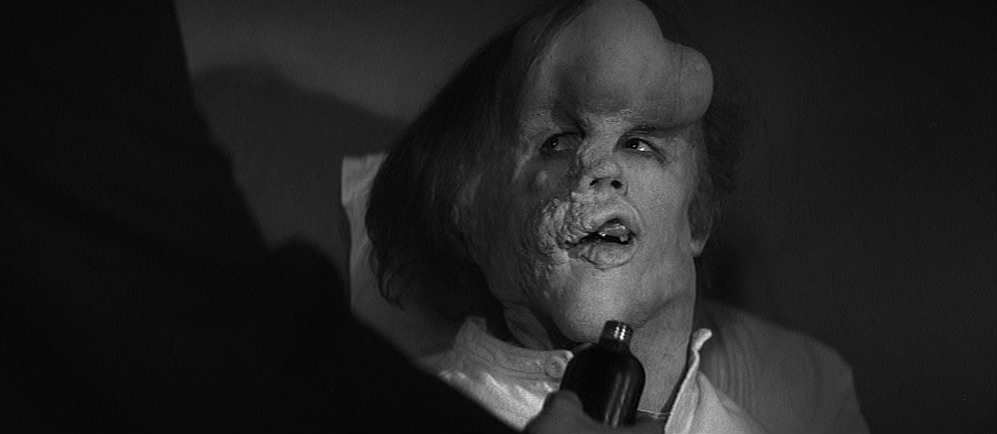

This is no simple task either given how far he has withdrawn into his own mind when Treves rescues him, unable to communicate even the most basic ideas. The white hood he wears in public also makes it difficult to read his face, and only allows him the vaguest connection to the outside world through a single, rectangular eyehole. In one scene however it becomes a portal which Lynch’s camera travels through into one of Merrick’s dreams, paralleling the blue box of Mulholland Drive a couple of decades later, and formally running The Elephant Man’s idiosyncratic surrealism up against Victorian London’s rigid cultural structures.

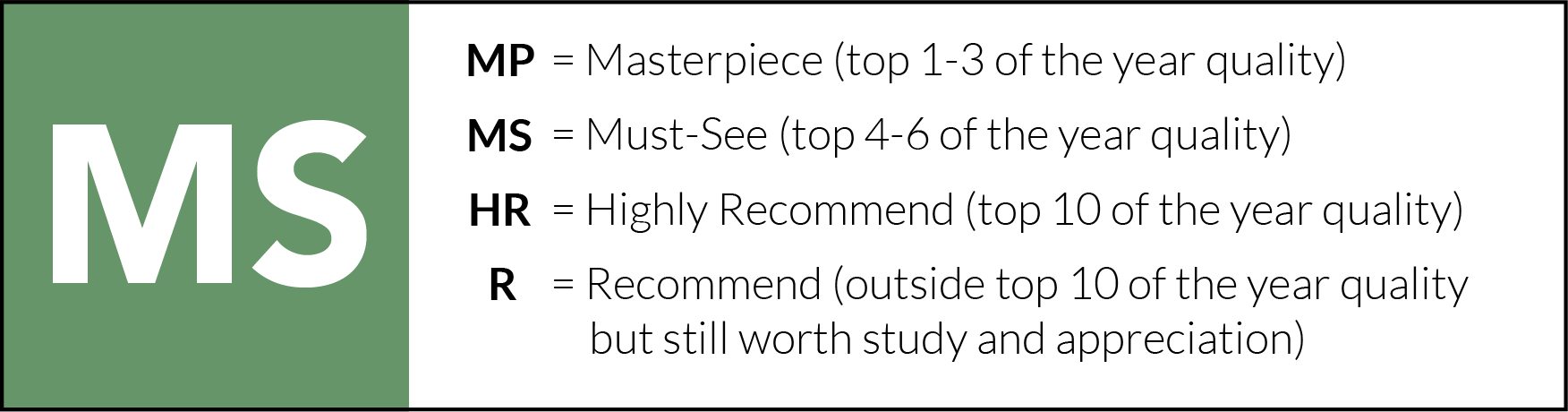

When Merrick’s mask comes off, it can often be just as hard to read his emotions given the outgrowths that impede his expression, though even beneath these layers of prosthetics John Hurt pours a great deal of sensitivity into his stammering speech. The arc that sees him transform from a carnival attraction rendered mute by his deathly fear of the world into a man who can dress in final formalwear and sit among theatre audiences is marvellously executed, centring his own self-perception as the key factor. As heart-wrenching as it is to watch him cornered by a clamouring crowd in one scene, his ability to cut their cruel shouts short with a guttural proclamation of his humanity marks a milestone in his self-acceptance.

“I am not an animal! I am a human being! A man!”

Not only is he a man, but he is wholly Christlike within the symbolic framework of Lynch’s narrative, taking on a spiritual significance in this world of corruption and exploitation. Despite his suffering, the widespread kindness he inspires is profound, breaking through the cruel pragmatism of 19th century London with a plea for compassion. There is a beautiful biblical bookend in his dialogue that reflects this too, with some of the first lines drawing from the Book of Psalms, and his last echoing Christ’s words as he hung on the cross, peacefully accepting death.

“It is finished.”

No longer is he haunted by nightmares of elephants. Now his mother speaks to him directly in his dreams, asserting that “nothing will die.” Horrifying surrealism has effectively transformed into magical whimsy, with even the play he is watching in a theatre mutates into a fantastical counterpoint, flying fairies across the stage in slow-motion and seeing his innocent imagination spring to life. Merrick’s physical limitations only hold him back so much in The Elephant Man. It is rather in the hypnotically idiosyncratic landscape of his own mind that Lynch locates the true key to an abiding, dignified happiness.

The Elephant Man is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green