Akira Kurosawa | 2hr 42min

Akira Kurosawa is no stranger to adapting Shakespeare, but the connection between King Lear and Ran was not always intentional. In its early pre-production stages, the inspiration was a parable regarding Japanese warlord Mōri Motonari, who is said to have taught his sons the value of family through demonstrating the unbreakable strength of three bundled arrows. It was only when the Shakespearean parallels started to organically emerge that Kurosawa began playing into its resonant character drama. Such rich source material is not enough on its own to ensure a successful final product though. It takes a director like Kurosawa to fully understand the full cinematic potential of a text like King Lear, balance that with dramatic power struggles between its key players, and transpose it onto a setting as alive with historical beauty as feudal Japan to create something this immense in scope and emotion.

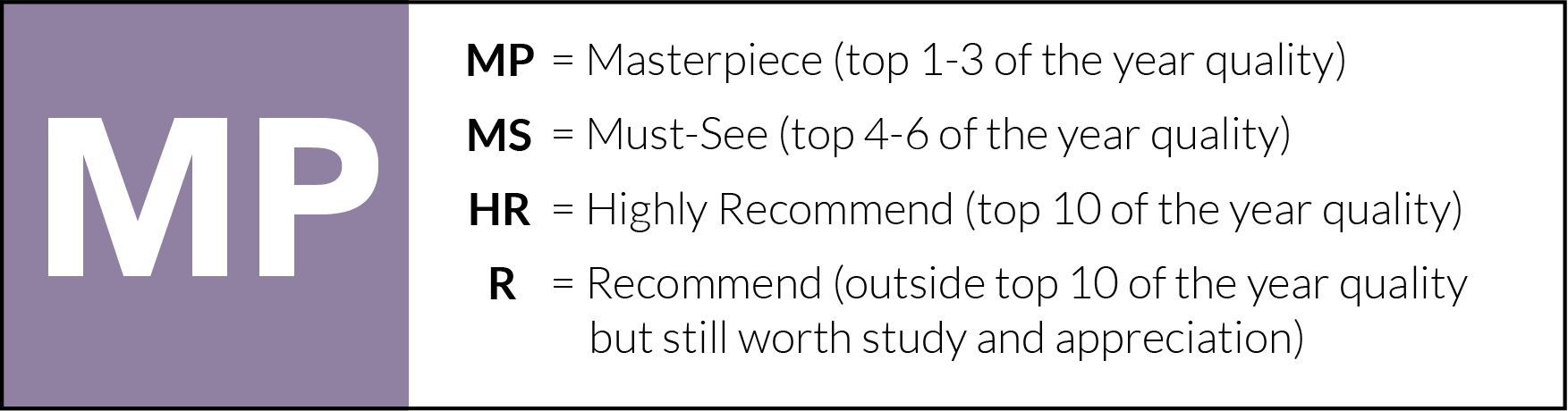

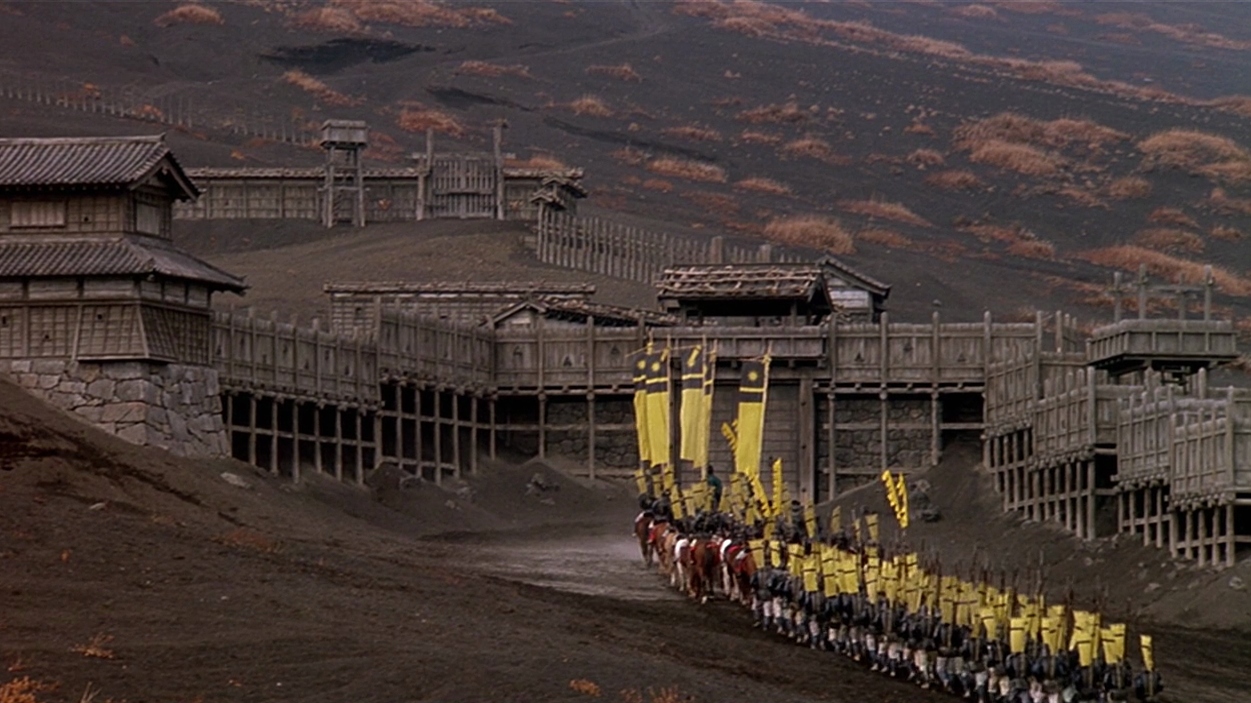

Sweeping battles are pitched against giant grey castles and rolling green hills, but it is in the thousands of costumed extras where Kurosawa lets loose with some of his most gorgeous colour compositions. The three main armies in question carry flags bearing the signature primary palettes of their leaders, charging in formations that demonstrate Kurosawa’s well-established flair for blocking and choreography on a colossal scale.

In one of the film’s most spectacular sequences, we watch in a long shot as red and yellow factions face off on either side of a burning fortress, its glowing flames complementing the heated colours below. In another, Kurosawa keeps his camera behind the galloping legs of a cavalry regiment to peer at the opposing military force firing their muskets from the remote safety of the woods, their targets falling into view right before our eyes. Few action films pay such attention to tactical warfare, but the conflicts of Ran are consistently authentic in how they are shaped by the intelligent strategising of leaders, rather than the basic, heroic actions of individuals.

It is only natural for Kurosawa to keep a distant perspective in epic battle scenes such as these, but even when he turns his camera to the unravelling family relations which have fuelled these conflicts, he still keeps his camera fairly remote in wide shots. After all, even on its most personal level Ran is still a family saga stretching over decades, and so capturing an ensemble of well-defined characters allows Kurosawa to paint out their relationships and statuses in immaculately blocked compositions.

Take two of the most fascinating players in this struggle – Hidetora Ichimonji, the elderly warlord, and Lady Kaede, his scheming daughter-in-law whose family he destroyed in his conquest for power. Though we witness few face-to-face encounters between the two, their relationship is as vividly illustrated as any of the others. Together, Tatsuya Nakadai and Mieko Harada deliver the two most outstanding performances of the film in these roles, patiently developing their characters across years of trauma and rage.

When we first meet Kaede, she has been married to Taro, Hidetoro’s eldest son, for many years. Perhaps for all this time she has been helplessly resigned to her station in life, grateful that she at least survived the massacre of her family. Perhaps she has been waiting for the day her husband will inherit the land that was stolen off her parents, so she can eventually claim it for herself. Either way, she is incredibly resourceful in her manipulations, quickly adapting to new developments by slyly attaching herself to whoever holds the most power at any given time. In the space of a single scene, we watch her threaten to kill, seduce, and then draw sympathy from Jiro, Hidetoro’s second eldest son. She has no other long-term objective than to see the downfall of the family which took everything from her, even at the expense of her own life, and this hardened sense of nihilism sticks with her right to the end.

Though Hidetora is our protagonist, he may also be considered the villain of the piece, having foolishly set in motion the sequence of events which lead to the conflict between his three sons. He is a man who built a life off of slaughtering thousands of innocents, and now in his old age he is left to powerlessly watch that empire crumble, ashamedly recognising that his own children may possess the same evil that resides within him. He is not granted a quick, easy death that might spare him the pain of life’s consequences, but instead he lives long enough for the anguish to wear away at his soul. His skin turns grey, his white hair grows long and wispy, and he mentally retreats into his past where he is haunted by the spirits of those he killed.

Within Hidetora’s perspective, Kurosawa frequently inserts formal cutaways looking up at clouds, as if searching for a sign of some divine power. When all is well in his domain, the sky is notably much lighter than when there is conflict, but with no other reassurance, Hidetora is left a lonely, raving madman, cut off from both the heavens and the earth.

The long shot that Kurosawa leaves us with ties this idea off on a particularly nihilistic note, lingering on Tsurumaru, a blind man who has only played a minor role in this narrative, but whose symbolic presence has been incredibly potent. Tapping his way across the edge of castle ruins, he stumbles and drops his precious image of Buddha to the bottom of a gorge. Viewed from a distance, Tsurumaru is but a tiny silhouette, and now without even the icon of his faith to protect him he is left with nothing. To Kurosawa, this is the entire world – ignorant to the danger which lies ahead of us, and abandoned by our gods. For all the epic battles and characters that fill out Ran’s immense, complex narrative, every single development is at its core motivated by a simple, seething bitterness towards humanity’s existential isolation.

Ran is currently available to rent or buy on iTunes and YouTube.

8 thoughts on “Ran (1985)”