Terry Gilliam | 2hr 12min

Describing a piece of fiction as Orwellian has become some sort of vague platitude to acknowledge a scathing attack on totalitarianism, yet few films fit the descriptor better than Brazil. The very concept of a man and a woman escaping an authoritarian government, making love, and falling right back into the government’s clutches is no doubt a familiar narrative to those familiar with ‘1984’. Where George Orwell’s Airstrip One was ruled by the indomitable force of Big Brother though, Terry Gilliam’s dystopian city envisioned in Brazil is a hilariously incompetent bureaucracy, far too caught up in its own procedures and trivialities to run a functioning society.

Jonathan Pryce’s protagonist Sam Lowry is introduced via his own dream as a winged knight, soaring through clouds and seeing visions of a mysterious woman. Later, he dreams of monsters roaming city streets, and a large robot used to subdue citizens. These fantasies may suggest an imaginative man out of step with his surroundings, yet their manifestations in reality also suggest something more surreal at work. Is Sam prophesising the future? Do his dreams actually have power to shape reality? Perhaps if this city could put its mind to something other than blunt commercialism and nonsensical data he might actually get answers.

The machines that this society has built to assist humans in their quest for rigidity are barely efficient themselves. Sam’s coffee machine swings around wildly, pouring boiling water over his toast. The elevator at his work malfunctions at the worst possible time. Even the catalyst for Brazil‘s entire plot stems from a fly falling into a teleprinter, causing it to stamp an incorrect name on a form. Few people are able to look past this clerical error and see the truth. Whatever is printed on a form becomes law.

Nothing signifies the distortion of something meaningful into a consumerist spending spree like the birth of Jesus Christ, and Gilliam is all too aware of the implications in setting this story at Christmastime. Tinsels, trees, and fairy lights are pathetically scattered around this depressingly grey city, and even a sign that hilariously reads “Consumers for Christ” mocks a society that has become stupidly aware of its own vapidity.

Of course, everything is constructed as one giant distraction though, and the utter disconnection between citizens and the social issues that surround them are milked for all their comedic value. There are terrorists on the loose, yet their explosive activities are nothing more than background noise to restaurant patrons who continue chatting away. As a string trio play a rendition of Hava Nagila, emergency responders gather quickly to put out the fire and rescue the wounded, and all the restaurant manager can do to maintain the feeble illusion of normalcy is place a partition between the his customers and the surrounding fuss.

This absurdist comedy was perfected by the Monty Python troupe, but Terry Gilliam simply extends on that in Brazil with his audacious visual gags and maximalist production design. In cluttering his frames with clunky machines, metallic pillars, and ducts, he traps Sam behind these enormous constructs, making him a prisoner of his own life.

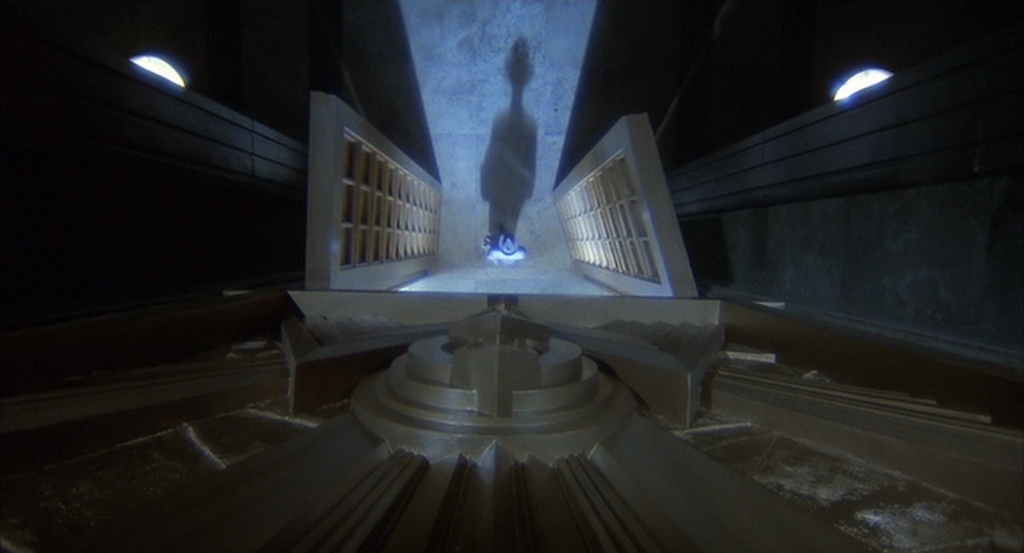

With the urban scenes in particular marking a tremendous feat of sci-fi world building, Brazil very much seems be Britain’s response to Blade Runner, building on its cyberpunk noir aesthetic with a heavy dose of surrealism and comedy. So convincingly detailed are the square block miniatures of this futuristic civilisation, it is easy to forget that these skyscrapers aren’t hundreds of metres tall – at least until Gilliam plays his own trick on the audience by pulling the camera back, amusingly revealing the falsity of one such miniature.

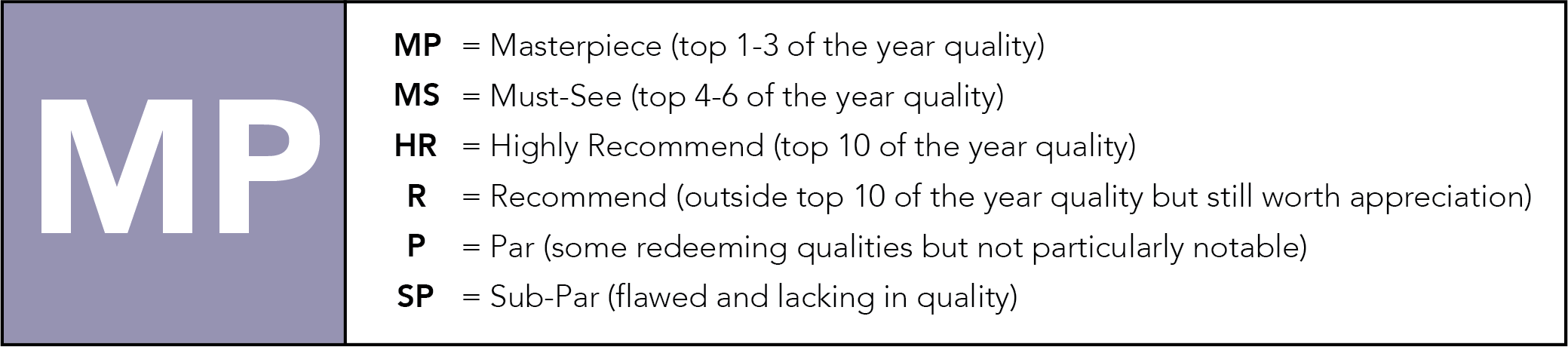

Most impressive of all Gilliam’s maddening set pieces though is the torture room – a large, cylindrical space that drops down into jagged, metal spokes fanning out from the centre. To lift this lunacy into the realm of complete insanity, Gilliam’s wide-angle lens distorts everything that little bit more. Jonathan Pryce’s face is the perfect canvas for these warped, low-angle close-ups too, as everything around him seems to spread outwards from his bulging eyes.

From here on, Brazil descends further into chaotic surrealism, with Sam making his eventual escape to live a content life in the countryside with Jill. It is suspiciously rushed and unearned, though everything falls into place with the crushing reveal that this entire sequence has only unfolded in his lobotomised dream state. As witless as the state is, their blunt power more than makes up for their incompetence, leaving Sam to happily indulge in his own imagination. Terry Gilliam’s construction of a futuristic Britain is visually daunting, but Brazil never shies away from the dark comedy of a government desperately out of touch with reality.

Brazil is currently available to stream on Mubi Australia, and to buy or rent on iTunes and YouTube.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green