“Shame on those who, during their puberty, murdered the person they might have become.”

Jean Vigo

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. L’Atalante | 1934 |

| 2. Zero for Conduct | 1933 |

Best Film: L’Atalante

L’Atalante is a fable of ruptured innocence, jealousy, and temptation, tugging at the seams of a fragile relationship between a skipper and his newlywed wife Juliette. It is a seminal early work of France’s poetic realism, showcasing the sort of cluttered mise-en-scène that Josef von Sternberg was similarly innovating in the early 1930s, as well as gorgeous location shooting around the industrial docks of Paris. Jean Vigo’s storytelling is classical, but his fondness for the avant-garde also reveals itself in the surreal, underwater visions of Juliette, romantically escaping the cinematic conventions of the era.

Most Overrated – L’Atalante

L’Atalante is rightfully beloved by many cinephiles, but not quite the 20th best film of all time as the TSPDT consensus would have us believe. Its grand ambitions in mise-en-scène, editing, and characterisation can be appreciated without placing it upon such a high pedestal, still giving Jean Vigo his due as a pioneer of French cinema in the 1930s. Perhaps 300 spots lower would suit it just fine, treading the border between Must-See and Masterpiece range.

Most Underrated – Nothing

Zero for Conduct is also a little overrated at #219 on TSPDT, so there are no real candidates here. For a man whose filmography is so short, Jean Vigo’s reputation in the cinephile community is extraordinary – and perhaps slightly inflated.

Gem to Spotlight – Zero for Conduct

At 43 minutes, Zero for Conduct achieves far more than most feature films do in two hours. It isn’t too difficult to imagine how Jean Vigo might have flourished during the French New Wave some 30 years later, though given the impact that Zero for Conduct bears upon François Truffaut, perhaps this would also defeat the point of its influence. The young director is evidently far ahead of his time, crafting a coming-of-age tale which revels in its carefree naturalism and youthful outlook. Vigo is economical indeed with his nonchalant pacing, smoothly shifting between vignettes that progressively mount a rising disenchantment among a cohort of schoolboys plotting to overthrow their tyrannical teachers.

Key Collaborator – Boris Kaufman

The cinematographer who later shot towering Hollywood classics such as 12 Angry Men and On the Waterfront got his start here with Jean Vigo, filming everything from his short documentaries to his narrative features. The two were virtually inseparable, experimenting in tracking shots, crowded mise-en-scène, location shooting, and dramatic camera angles right up until Vigo’s untimely death at age 29.

Key Influence – Sergei Eisenstein

Jean Vigo possesses a clear affinity for Eisenstein’s socialist ideals as a filmmaker, seeking to break free of artistic constraints by similarly liberating his characters from their own metaphoric chains. This is clearest in the schoolyard revolution of Zero for Conduct, emphasising cohesive units over individuals in what Eisenstein labelled a ‘monistic ensemble’ – a sense of group identity achieved through complete visual unity. He was not quite operating at the same level as the trailblazing Soviet montagist, but when his editing turned towards the abstract, his crafty manipulations in the cutting room moulded the flow of time itself.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

The story of Jean Vigo’s career as a director is tragically brief. Two short documentaries, a featurette, and a feature film make up his entire resume, and as mentioned before, L’Atalante does the heavy lifting for his critical reputation. He was an early pioneer of poetic realism, though where his contemporaries were concerned with notions of fate and morality, his films were pervaded by a revolutionary sensibility – no great surprise for the child of a militant anarchist.

Vigo established his sympathies for the downtrodden right from the start in À propos de Nice, creatively documenting the social inequalities among the people of Nice. It wasn’t until his featurette Zero for Conduct though that he found the narrative tools to give this theme cinematic form, turning a schoolboy rebellion into a scaled-down French Revolution. There is a tension between order and chaos in his blocking, often captured in high angles that frame the ensemble’s synchronised formations, and which would soon prove to be his trademark shot.

The revolt in Vigo’s final film L’Atalante is quieter and more psychological, with married couple of Jean and Juliette rejecting bourgeois ideals in favour of emotional authenticity and personal freedom. The boat which they turn into their home is a strong metaphor here, drifting along the canals of France without being anchored to any single port. The accomplishment of mise-en-scène is also a step up, making for crowded, claustrophobic interiors that deny these characters any chance of privacy, though at the same time Vigo possesses an almost utopian faith in the community they entail. L’Atalante is far more lyrical than it is playful, but this hymn to love’s endurance is just as impassioned as Zero for Conduct’s celebration of youth.

Both these films are lean, yet expansive in feeling. Vigo avoids redundancy, favouring vignettes and emotionally resonant beats that accumulate meaning rather than deliver it through exposition. As children tease each other in Zero for Conduct, the film itself becomes a prank on authority, while the eccentric antics of Père Jules in L’Atalante imbues its romance with whimsical comic relief.

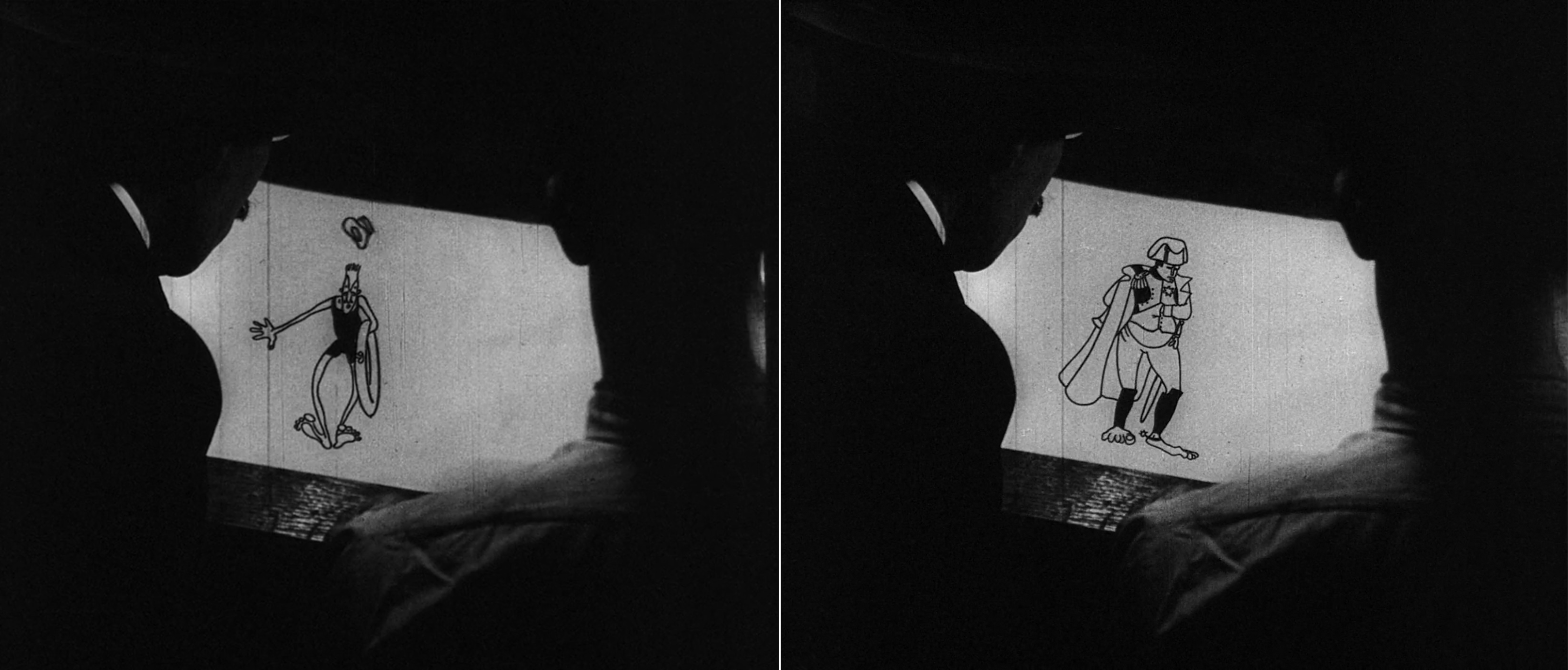

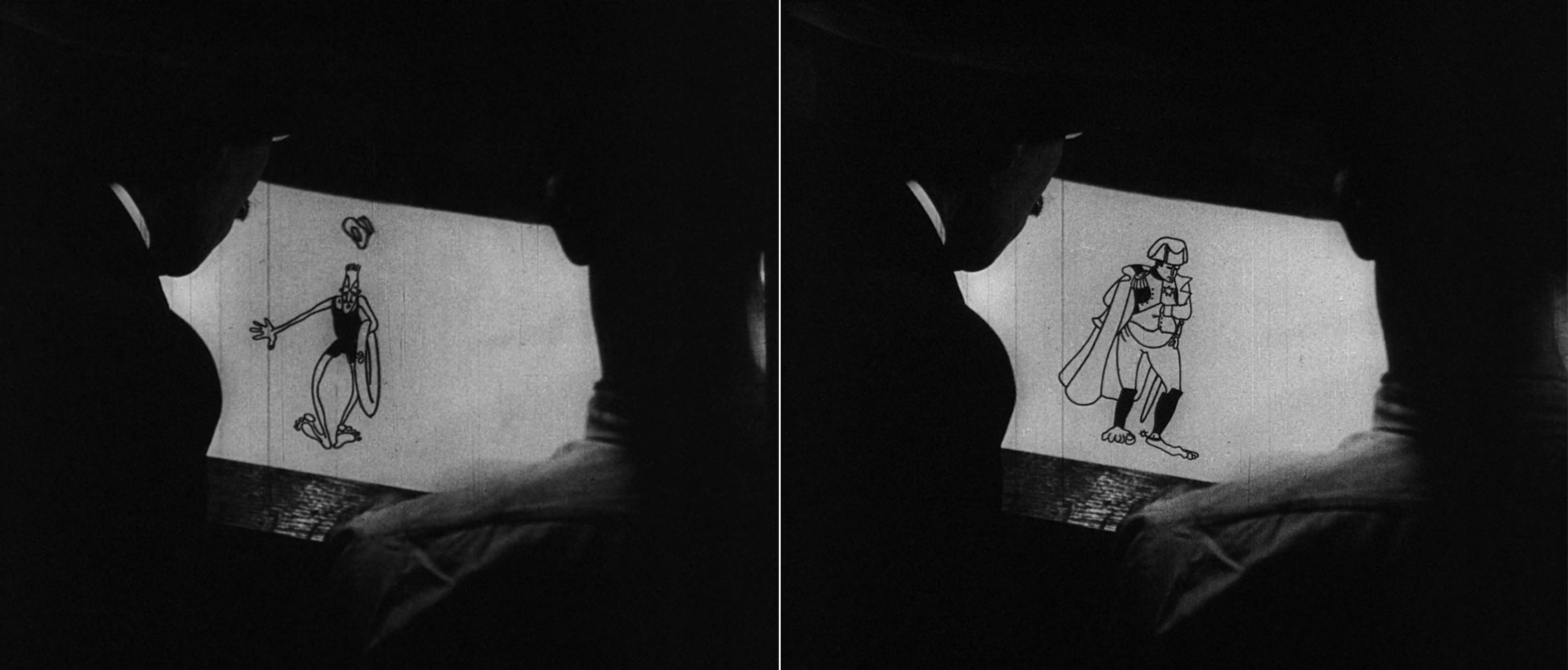

Vigo often takes his spirited, formal experimentation a step further though, paving the path to freedom through brief moments of transcension when reality gives way to surrealism. Animated caricatures leap to life with form-shattering irreverence in Zero for Conduct, and at its most awe-inspiring, the schoolboys’ joyous mutiny revels in one of cinema’s earliest displays of slow-motion. Meanwhile, L’Atalante conjures underwater visions of love through surreal dissolves and double exposure effects, sinking us into Jean’s aching, disorientated mind as he dives beneath the Seine.

With Zero for Conduct facing censorship issues and the final edit of L’Atalante escaping his artistic control, Vigo never reaped the financial reward for his films. At age 29, he died of tuberculosis, a mere month after L’Atalante’s release. Nevertheless, his cinematic legacy was already cemented, romantically liberating cinema from convention in pursuit of emotional and political truth.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1931 | À propos de Nice | Unrated (documentary) |

| 1933 | Zero for Conduct | MS |

| 1934 | L’Atalante | MS/MP |