Philip Barantini | 4 episodes (51 – 65 min)

In a small English police station, 13-year-old Jamie Miller is charged with the murder of his classmate, Katie Leonard. Back at school, an entire community is left reeling with confusion and grief over what has unfolded. In a youth detention centre, Jamie’s motives are uncovered by a forensic psychologist, and some months later his family continue to grapple with the long-term consequences in their own home. Four snapshots across thirteen months are all that Philip Barantini needs to uncover the humanity in the horror of Adolescence, plunge into its despairing depths, and lift this crime beyond the sort of freak occurrence that most people are fortunate enough to only ever see in news headlines.

Where a lesser series would thinly spread its sprawling drama across dozens of episodes, Adolescence weaves the fragmented nature of television into its very structure, dedicating an hour at a time to its characters’ messy lives. It is not an anthology of self-contained stories, but neither does it maintain the straightforward continuity that we often expect from serial dramas, letting us fill in the days and months that separate episodes. As such, its narrative economy is remarkably efficient, unravelling four vignettes in real time while intertwining the movements of police officers, students, and relatives.

Barantini’s stylistic conceit of playing out each episode in single, continuous takes must be credited for our immersion in this harrowing study of modern-age masculinity. Right from the in media res opening of episode 1, we are launched into the police force’s raid of the Miller residence, sharing in the same shock as Jamie’s panicked family as he is arrested. The handheld camerawork keeps us in Barantini’s tight grip, disorientating us as we move with Jamie from the house into the police van where we finally get a moment to collect ourselves. In the absence of cuts, we sombrely sit with him for several minutes during his transportation to the police station, tuning out the adults’ muffled speech while a tense, ticking score takes over. The sheer length of sequences like these only deepens our discomfort in Adolescence, growing our dread throughout this first episode.

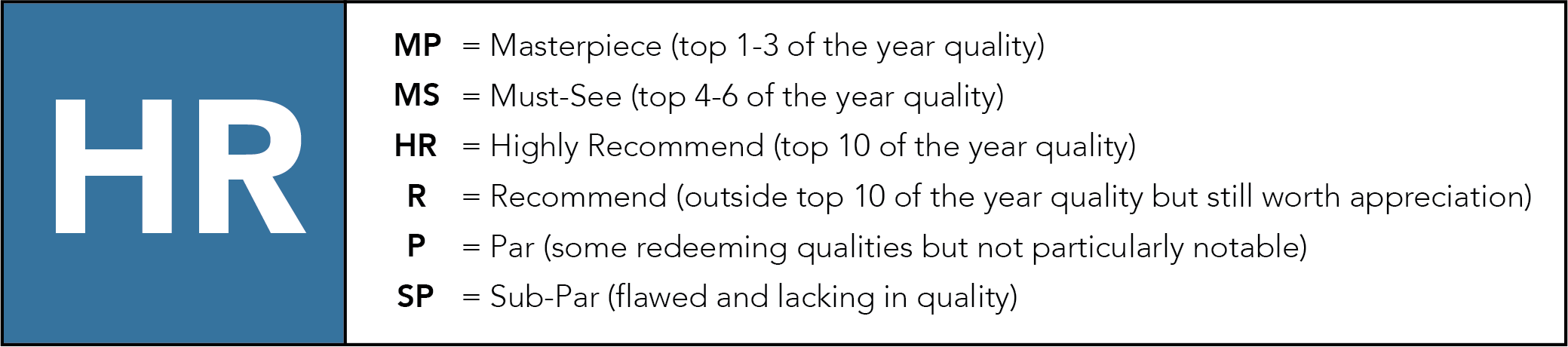

When Jamie’s mug shot and fingerprints are taken, again we hang on the unspoken guilt written across his face, while the agonising humiliation suffered by his father Eddie is given an agonising close-up during the young teen’s strip search. In the consultation room, Jamie’s blue jumper blends in with the muted, melancholy tones of the walls around him, where the camera tentatively circles the emergence of truth. Jamie was caught on CCTV footage stabbing Katie to death in a parking lot the previous night, we eventually learn, effectively rupturing the innocence of a community which never believed such a barbaric act could be committed by one of their own – and least of all by a child.

Episode 2 is set only a couple of days later, though it delivers an impressive sense of scale by widening its focus to the staff and students at Jamie’s school, many of whom become witnesses in DI Luke Bascombe’s investigation. With his son Adam only a few years above Jamie, his personal life is not entirely removed from this case, and in their emotionally estranged relationship we begin to see patterns emerge between the fathers and sons of Adolescence. Here, Barantini locks onto the social influences which slyly insinuated themselves in Jamie’s life, mixing a lethal Gen Z cocktail of cyberbullying and incel propaganda with the sort of male insecurities even older generations would recognise.

This episode features what may be Barantini’s singularly most ambitious shot, traversing the school grounds, classrooms, and offices to reveal the interconnectedness of the local community. The camera often hitches onto characters as they move from one location to the next, linking conflicting accounts of Jamie and Katie’s relationship to a secret emoji language, and the missing murder weapon to Jamie’s friends. During its final minutes, Barantini even seamlessly lifts the camera into a drone shot flying over the entire neighbourhood to a choral rendition of ‘Fragile’, echoing its mournful lyrics as it eventually descends to witness a mournful Eddie laying flowers at the site of Katie’s murder.

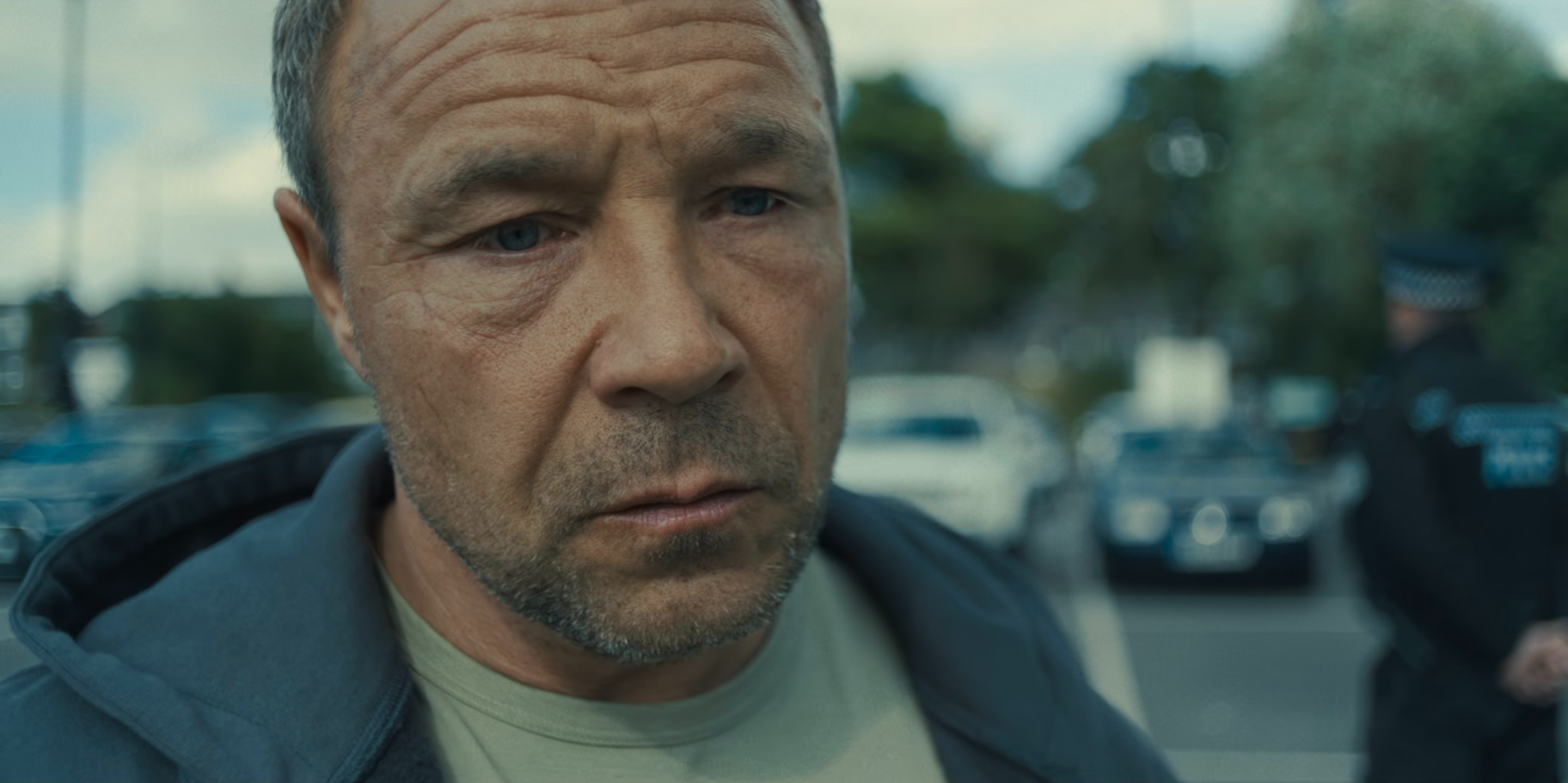

With all this said, the greatest hindrance to Barantini’s long takes are Adolescence’s lengthy dialogue scenes, often leaving the camera to wander without aim or purpose. Within these moments, its ambitions fall far behind other one-take films such as Birdman or Victoria, and this especially becomes restrictive in the single room setting of episode 3. The staging in Jamie’s detention centre is more akin to a play than anything else, focusing on his examination by forensic psychologist Briony Ariston, though in exchange young actor Owen Cooper is given a platform to deliver some of the most outstanding acting of the series.

In Jamie’s frustration at Briony’s line of questioning, we see a teenage boy who can’t quite grasp his own emotions, resisting any attempt to probe deeper in fear of what he may find. “Are you allowed to talk about this?” he uneasily asks about half a dozen times when the topic turns to sex, repeating the phrase almost as often as his baseless claim – “I didn’t do it.” Unable to reconcile his guilt and dignity, he desperately tries to convince himself of his innocence, denying the traumatic reality of his actions. When this cognitive dissonance is threatened, he falls back on intimidation tactics to retake control from Briony, throwing insults and even a chair in bitter anger. She is perturbed, yet actress Erin Doherty holds a steel nerve against his torment, only ever revealing how deeply this experience cuts away from his judgemental eyes.

In Jamie’s quieter moments too, Cooper’s angsty performance remains strong, unassumingly being coaxed into contemplating his relationship with his father. When he asked if he is loving, Jamie’s responds is dismissive – “No, that’s weird” – and as Adolescence moves into episode 4, Barantini allows this regretful man to take the final word on the matter. Thirteen months after the murder, the Miller family wrestles with the long-term ramifications of Jamie’s actions which have singled them out in their community as pariahs. Glimmers of healing emerge during their drive to the local hardware store, looking for paint to cover up the graffiti left on Eddie’s van, but even this simple outing cannot escape the cruel taunts of teenagers or conspiracy theorists chillingly advocating for Jamie’s innocence.

Finally exhausting his patience, Eddie throws his fresh tin of paint all over the van, and in this moment we see flashes of the boy who only last episode tossed a chair in anger. Retreating to Jamie’s room with his wife Manda, Eddie ponders where it all went wrong, at which point the dialogue begins spell out its themes a little too directly. The screenplay weakens here, exchanging subtext for literalism, yet Barantini nevertheless succeeds in bringing Jamie’s story full circle back to his biggest influence.

Eddie’s failure isn’t as simple as him being a bad father – that much is clear from the anguished guilt of Stephen Graham’s performance. “If my dad made me, how did I make that?” he laments, beginning to recognise how deeply entrenched his worst habits are in his own childhood and parenting. As he cries into Jamie’s bed, the blues we observed in the police station return in darker shades to envelop him in a familiar sorrow, yet this time allowing an honest outpouring of suppressed emotions. It is a catharsis that we have eagerly awaited in Adolescence, and one that is especially earned through the cumulative weight of Barantini’s long, restrained takes, pushing a quiet form of insistence – not only that we bear witness to this teenager’s shattering crime, but to the raw, fragmented, and unresolved mess left behind.

Adolescence is currently streaming on Netflix.