Steven Zaillian | 8 episodes (44 – 76 minutes)

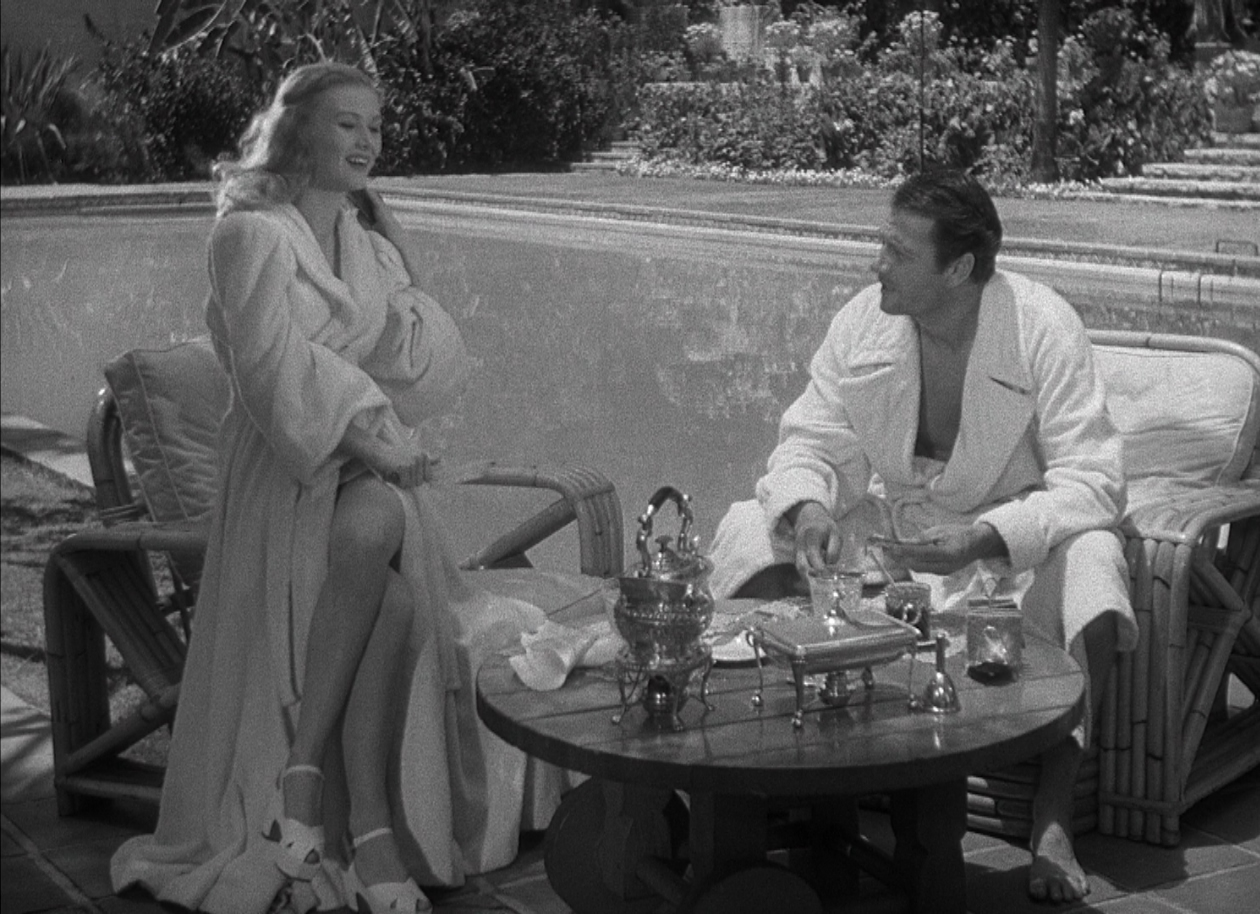

When spoiled heir Dickie Greenleaf catches Tom Ripley trying on his expensive clothing, the assumption that his new friend might be gay is only half-correct. Queer readings of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley are nothing new, and Steven Zaillian is not ignorant to them in his television adaptation, though the icy contempt and admiration that are wrapped up in Tom’s repression also paint a far more complex image of class envy. Tom does not wish to be with Dickie, but to become him, and the depths to which he is willing to sink in this mission reveal a moral depravity only matched by his patience, diligence, and cunning.

Of all the qualities that vex Tom about Dickie, it is his complete lack of personal merit that is most maddening, deeming him unworthy of the lavish lifestyle funded by his wealthy father. While Dickie admires the cubism of Picasso and even proudly owns his artworks, his attempts at recreating that distinctive, abstract style fall short, just as his girlfriend Marge displays little talent in her writing and his friend Freddie is no great playwright. Money might buy the bourgeoisie false praise, yet no amount of riches can endow upon them the ingenious intuition that history’s greatest artists naturally possess, and which Tom nefariously manipulates to earn what he views as his unassailable right.

It takes the sharp, opportunistic mind of a con artist to conduct a scam as multifaceted as that which Tom executes here, murdering and stealing Dickie’s identity while carefully navigating the ensuing police investigations. Though Tom adopts his victim’s appreciation of Picasso for this ploy, Zaillian also introduces another historic painter as an even greater subject of fascination in Ripley. The spiritual affinity that Tom feels for Baroque artist Caravaggio is deepened in the parallels between their stories, both being men who commit murder, go on the run, and express a transgressive attraction towards men. Though living three centuries apart, these highly intelligent outcasts are mirrors of each other – one being an artist with a criminal background, and the other a criminal with a fondness for art.

At the root of this comparison though, perhaps Tom’s appreciation may simply stem from the aesthetic and formal qualities of Caravaggio’s paintings, portraying biblical struggles with an intense, dramatic realism that was considered groundbreaking in Italy’s late Renaissance. When Tom gazes upon three companion pieces depicting St. Matthew at the grandiose San Luigi dei Francesi cathedral in Rome, they seem to come alive with the sounds of distant, tortured screaming, blurring the thin boundary between art and observer. With this in mind, Zaillian’s primary inspiration behind Ripley also comes into focus, skilfully weaving light and shadow through his introspective staging of an epic moral battle as Caravaggio did four hundred years ago.

Though the rise of cinematic television in recent years has seen film directors take their eye for photography to the small screen, one can hardly call Zaillian an auteur. This is not to take away from his impressive writing credits such as Schindler’s List, Gangs of New York, and The Irishman, but the spectacular command of visual storytelling in Ripley is rare to behold from a filmmaker whose directing has often been the least notable parts of his career.

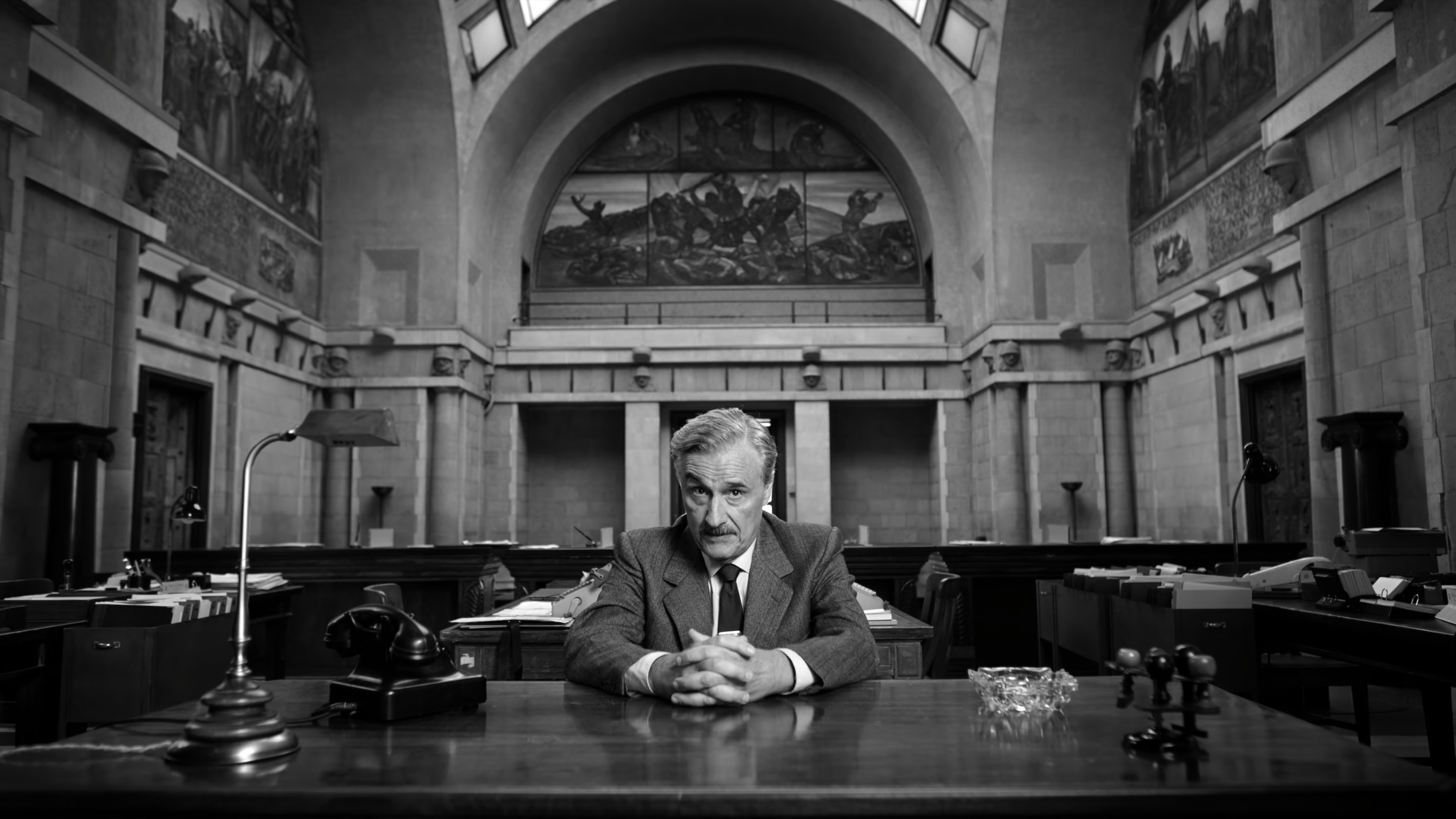

Robert Elswit’s high-contrast, monochrome cinematography of course plays in an integral role here, rivalling his work on Paul Thomas Anderson’s films with superb chiaroscuro lighting and a strong depth of field that basks in Italy’s historic architecture. Elswit and Zaillian’s mise-en-scène earn a comparison to Michelangelo Antonioni’s tremendous use of manmade structures here, aptly using the negative space of vast walls to impede on his characters, while detailing the intricate, uneven textures of their surroundings with the keen eye of a photographer. The attention paid to this weathered stonework tells the story of a nation whose past is built upon grand ambition, yet which has eroded over many centuries, tarnishing surfaces with discoloured stains and exposing the rough bedrock beneath worn exteriors.

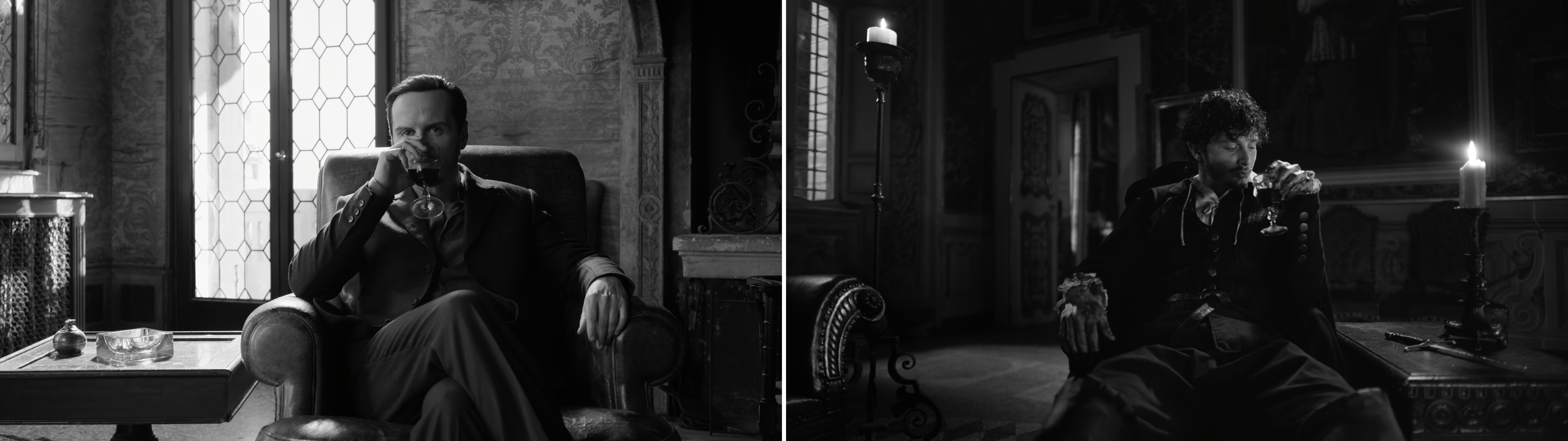

Conversely, the interiors of the villas, palazzi, and hotels where Tom often takes up residence couldn’t be more luxurious, revelling in the fine Baroque furniture and decorative wallpaper that only an aristocrat could afford. The camera takes a largely detached perspective in its static wide shots, though when it does move it is usually in short panning and tracking motions, following him through gorgeous sets tainted by his corrosive moral darkness.

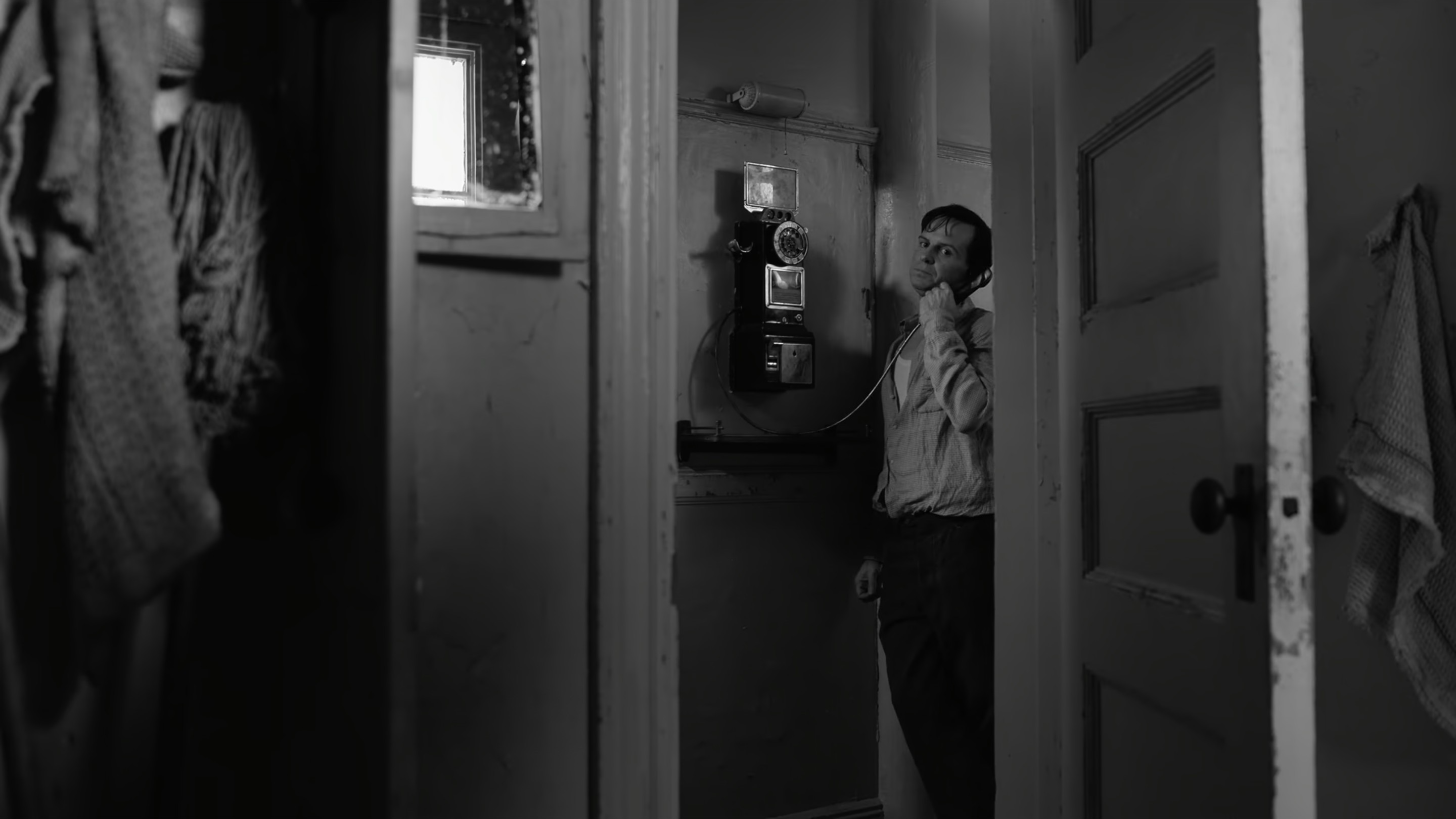

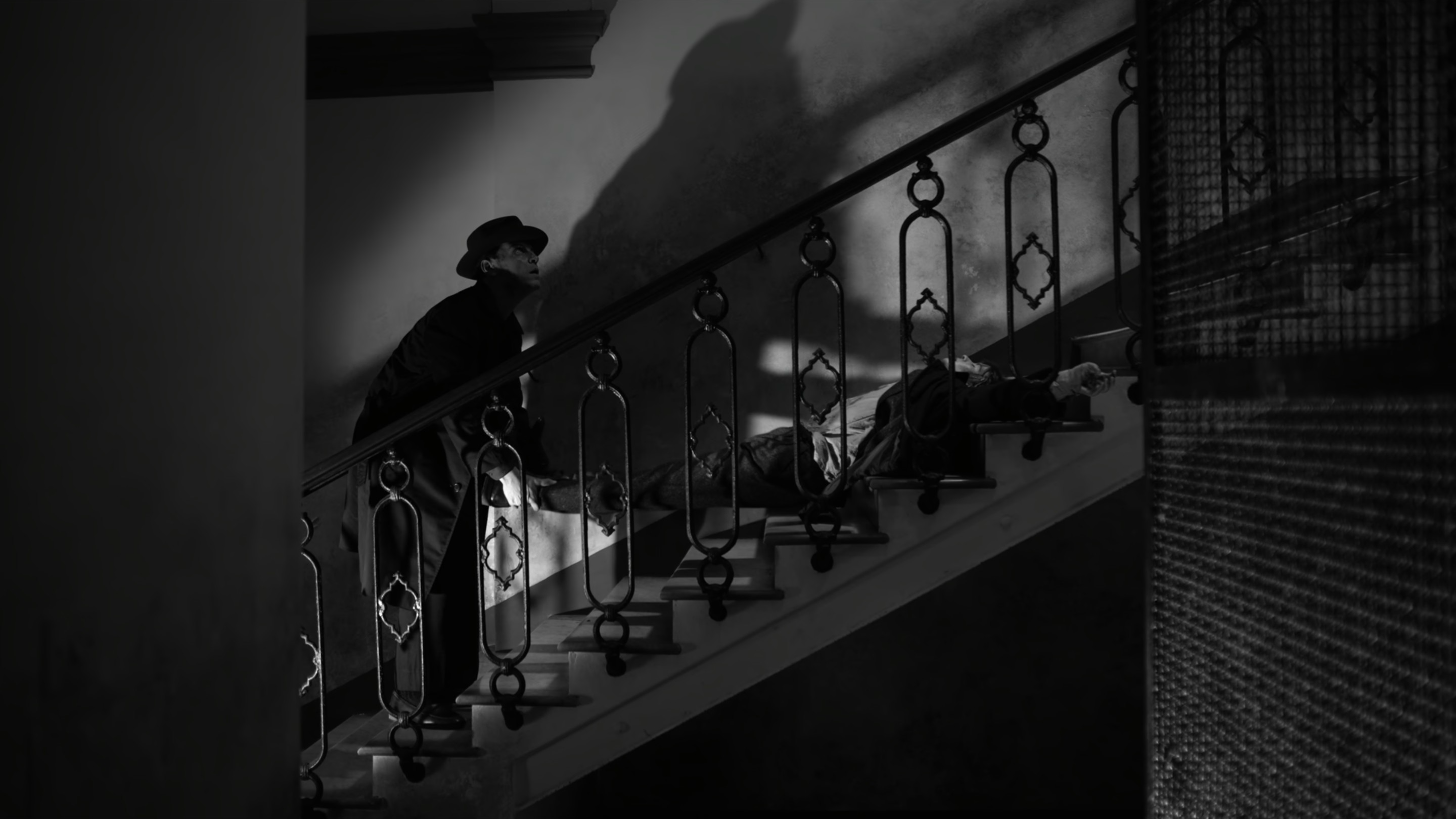

In effect, Ripley crafts a labyrinth out of its environments, beginning in the grimy, cramped apartment buildings of New York City and winding through the bright streets and alleys of Italy. Zaillian’s recurring shots of stairways often evoke Vertigo in their dizzying high and low angles, with even the flash-forward that opens the series hinting at the gloomy descent to come as Tom drags Freddie’s body down a flight of steps. Elsewhere, narrow frames confine characters to tiny rectangles, while those religious sculptures clinging to buildings around Italy direct their unblinking gazes towards Tom, casting divine judgement upon his actions.

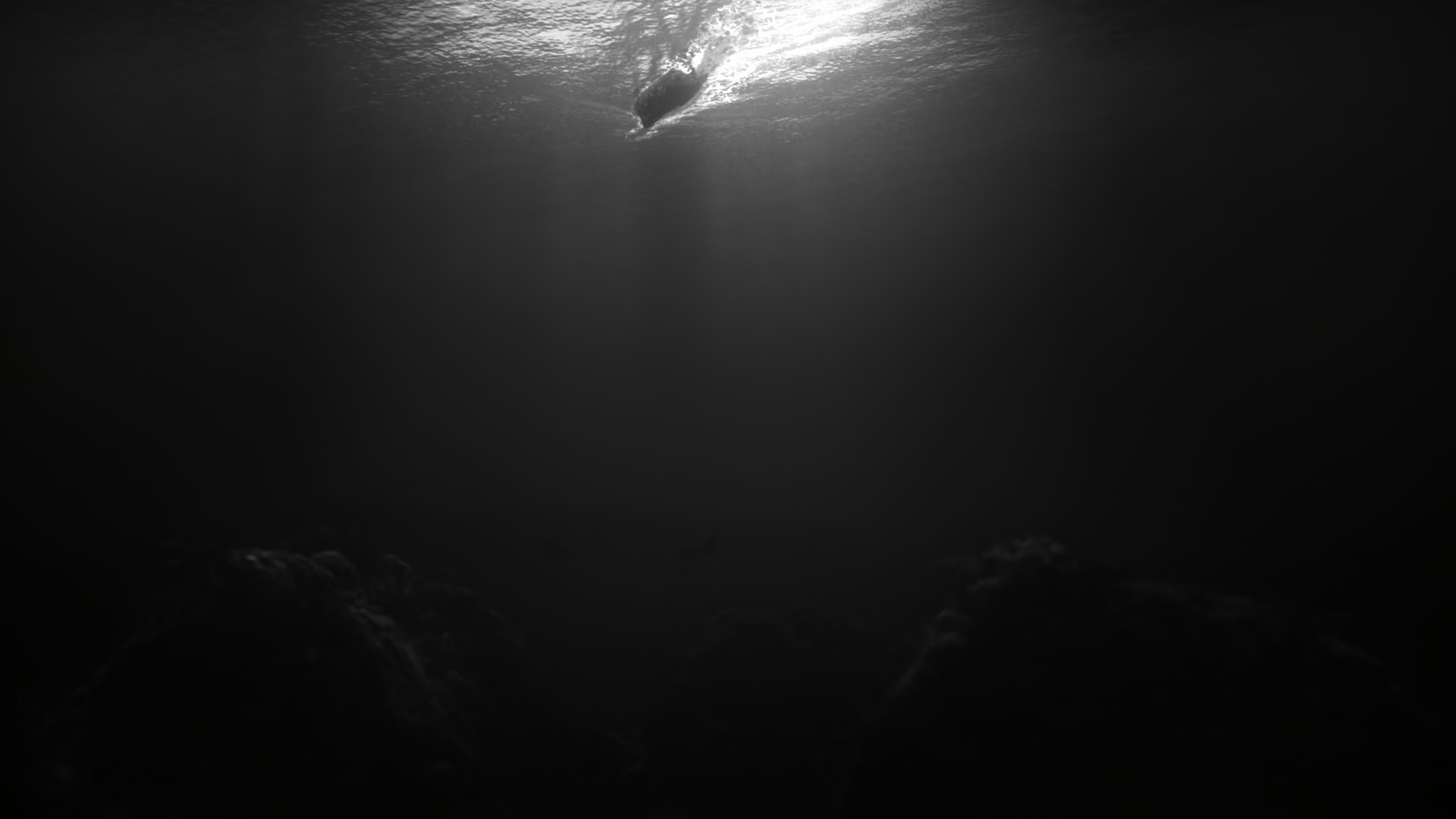

As oppressive as these tight spaces may be, they are where Tom is most in control, though Zaillian is also sure to emphasise that the opposite is equally true. The only place to hide when surrounded by vast, open expanses of ocean is within the darkness that lies below, and Tom’s phobia is made palpable in a visual motif that plunges the camera down into that suffocating abyss. This shot is present in nearly every episode of Ripley, haunting him like a persistent nightmare, though Zaillian broadens its formal symbolism too as Tom seeks to wield his greatest fear as a weapon against others.

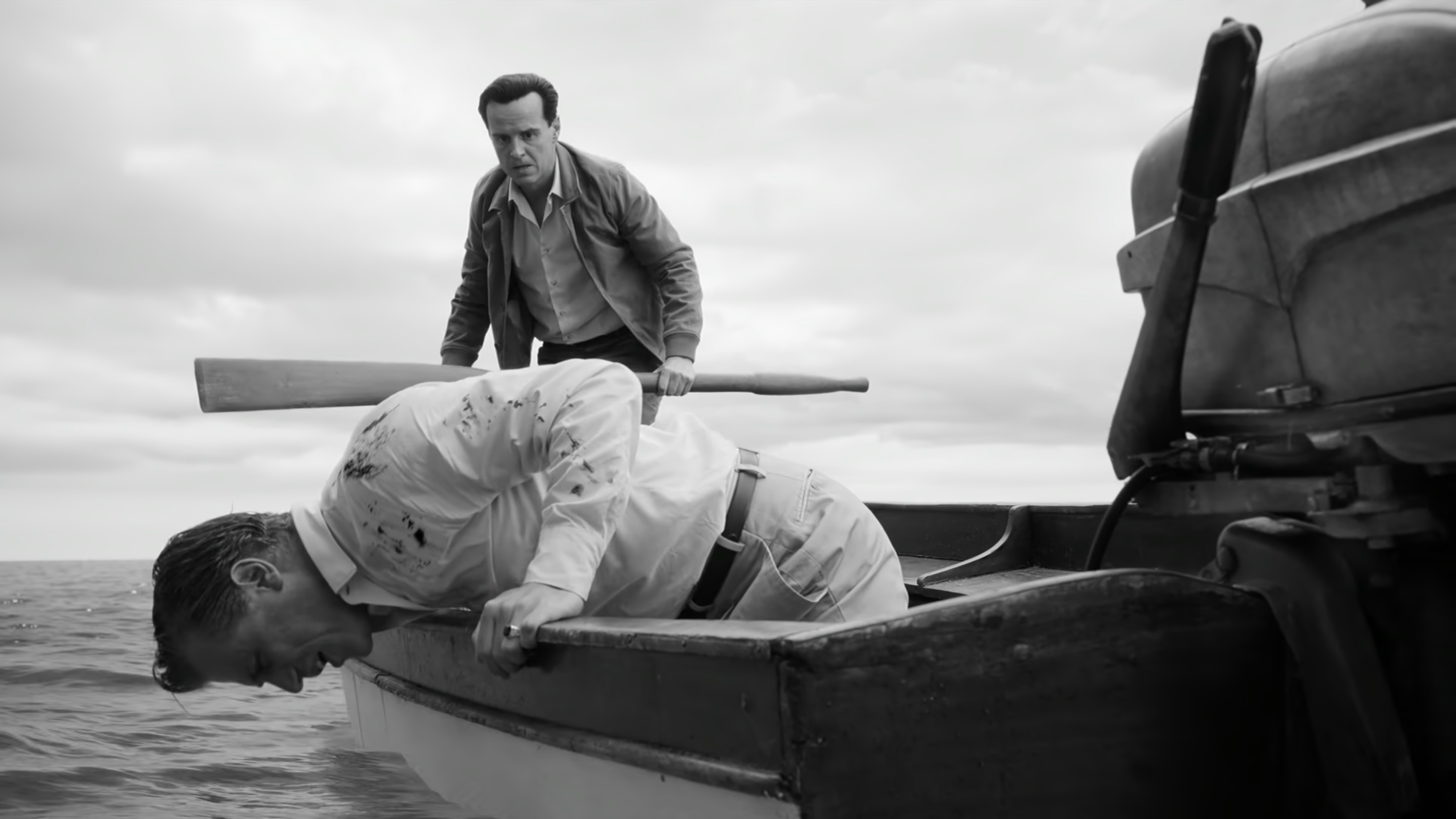

Most crucially, Tom’s murder of Dickie upon a small boat in the middle of the ocean marks a tipping point for the con artist, seeing him graduate to an even more malicious felony. Zaillian conducts this sequence with taut suspense, entirely dropping out dialogue from the moment Tom delivers the killing blow so that we may sit with his discomforting attempts to sink the body, steal Dickie’s coveted possessions, and burn the boat. From below the surface, the camera often positions us gazing up at the boat’s silhouetted underside with an unsettling calmness. Equally though, the sea is also a force of unpredictable chaos, threatening to drag Tom into its depths when his foot gets caught in the anchor rope and knocking him unconscious with the out-of-control dinghy.

Even when Tom manages to make it out alive, his continued efforts to cover his tracks bear resemblance to Norman Bates cleaning up after his mother’s murder in Psycho, deriving suspense from his systematic procedures of self-preservation across 25 nerve-wracking minutes. Within a two-hour film, a scene this long might otherwise be the centrepiece of the entire story, yet in this series it is simply one of several extended sequences that unfolds with measured, focused resolve.

Unlike most commercial television, there are no dragged-out plot threads or over-reliance on dialogue to push the narrative forward either. As such, Zaillian recognises the unique qualities of this serial format in a manner that only a handful of filmmakers have truly capitalised on before – Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage comes to mind, or more recently Barry Jenkins’ The Underground Railroad. By structuring Patricia Highsmith’s story around roughly hour-long episodes, each scene unfolds with a patient attention to detail, unencumbered by the constraints of limited run times while maintaining a meticulous narrative economy.

Specifically crucial to the development of Ripley’s overarching form are Zaillian’s recurring symbols, woven with sly purpose into Tom’s characterisation. The refrigerator that Dickie purchases in the second episode is a point of contention for Tom, representing a despicably domestic life of stagnation, while the precious ring he steals is proudly worn as an icon of status. After Freddie starts investigating his mysterious disappearance though, the glass ashtray which Tom viciously beats him to death with becomes the most wickedly amusing motif of the lot, laying the dramatic irony on thick when the police inspector visits the following morning and taps his cigarette into it. Later in Venice, Tom even goes out of his way to purchase an identical ash tray for their final meeting, for no other reason than to gloat in his deception.

This arrogant stunt speaks acutely to Andrew Scott’s sinister interpretation of Tom Ripley, especially when comparing him against previous versions performed by Alain Delon and Matt Damon. Scott is by far the oldest of three at the time of playing the role, and although this stretches credulity when the character’s relative youth comes into question, it does apply a new lens to Tom as a more experienced, jaded con artist. He does not possess the affable charisma of Delon or Damon, but he delivers each line with calculated discernment, understanding how a specific inflection or choice of word might turn a conversation in his favour. He realises that he does not need others to like him, but to merely give him the benefit of the doubt, allowing enough time to review the situation and recalibrate his web of false identities. After all, how could anyone trust those onyx, shark-like eyes that patiently scrutinise his prey when they aren’t projecting outright malice?

Scott’s casting makes even more sense when considered within the broader context of Zaillian’s adaptation, leaning into the introspective nature of Tom’s nefarious schemes rather than their sensational thrills. The question of what exactly constitutes a fraud is woven carefully through each of Ripley’s characters, mostly centring around Dickie’s class entitlement and Tom’s identity theft, though even manifesting in the police inspector’s passing lies about his wife’s hometown. The rest of society wears false masks to get ahead, Tom reasons, so why shouldn’t he join in the game?

It is no coincidence that the disguise he wears when pretending to be the ‘real’ Tom Ripley so closely resembles the representation of Caravaggio that we meet in the final episode. If anything, this is the truest version of Tom that he has played thus far, and Zaillian’s magnificent conclusion brings that comparison full circle with a dextrous montage of mirrored movements and graphic match cuts. Our protagonist is not some demon born to wreak havoc on the world, but rather a man who has always existed throughout history, seeking to climb the ladder of opportunity with a sharpened, creative impulse and moral disregard. As Ripley so thoroughly demonstrates in studying the mind of this genius, there may be no profession that better captures humanity’s enormous potential than an artist, and none that sinks any lower than a charlatan.

Ripley is currently streaming on Netflix.