Bong Joon-ho | 2hr 17min

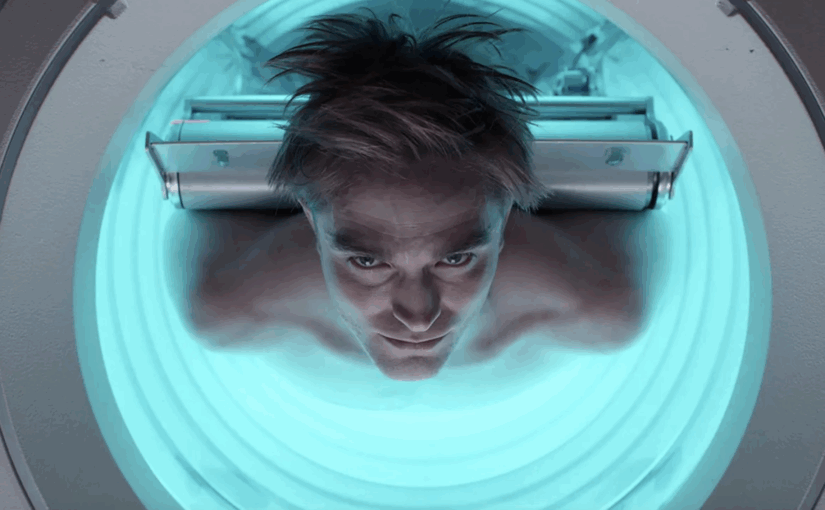

By the time Mickey 17 is printed into existence, there have already been 16 prior Mickeys that have been stabbed, gassed, burnt, and killed any number of ways – all in service of humanity’s expedition to the frozen planet Niflheim of course. He is a cog in the machine of colonisation to be sent on suicide missions and used as test subjects, often without being warned of the situation he is getting into. With his memories being downloaded into each new clone upon the death of its predecessor, it initially seems as if the collective Mickeys are a single being, blessed with immortality and cursed to live a Sisyphean existence. When a mix-up leads to his seventeenth incarnation coming face to face with Mickey 18 though, death no longer feels like a fleeting bump in the road. Once a Mickey dies, his consciousness truly ceases to exist, even as near-identical future copies take his place.

True to Bong Joon-ho’s savage class critiques, Mickey 17 uses its high concept sci-fi premise to delineate the underpinnings of identity in a capitalist system – particularly one which explicitly labels its workers “expendables.” The labour exploitation here is a continuation of similar concerns illustrated in Parasite, though the satire bears much closer resemblance to the harsh dystopia of Snowpiercer and Okja’s whimsical eco-fable. While Mickey strives to hold onto his dignity, expedition leader and thinly veiled Trump parody Kenneth Marshall wields him as a weapon against Niflheim’s native alien species, colloquially known as creepers, trampling over subservient allies and defenceless enemies to claim this territory as his own.

With Robert Pattinson giving perhaps his most broadly comedic performance to date, what could have been a gritty tale of class oppression and uprising is instead played with a dark sense of humour, narrated by Mickey’s timid, nasally voiceover. Through him we are given the backstory on how he ended up here, the grim state of civilisation on Earth, and the purpose of this interstellar mission – though when we are still getting through the exposition an hour in, Bong’s worldbuilding begins to wear a bit thin. There isn’t a whole lot of efficiency to this first act, so it is largely thanks to his incredible imagination that we remain in the grip of his storytelling, examining the ethical and social implications of a society built on the careless turnover of its working class.

Although Mark Ruffalo plays the main antagonist here with cartoonish sensibilities, Toni Collette’s wit is far sharper as his uncomfortably affectionate wife Ylfa. Her absurd obsession with sauces goes beyond mere idiosyncrasy, and becomes an icon of upper-class indulgence in a totalitarian environment of strictly controlled calorie intake, ensuring the workers do not have energy for prohibited recreational activities such as intercourse. Just as Kenneth and Ylfa are reminding the crew of such rules though, Bong’s parallel editing weaves in this treasonous act between Mickey and his girlfriend Nasha with subversive passion, setting both up as the strongest voices of dissent on the spaceship.

That Mickey 17 seems to have a little too much on its mind unfortunately weakens the narrative here, as for quite a while it seems that Mickey 18’s problematic arrival is secondary to Kenneth’s broader conflict with the creepers. It takes a sudden provocation and shift in character motive for Bong to start forcing these plot threads together, delivering a firm anti-imperialist statement as the native species begins to retaliate against their oppressors.

Designed as an outlandish cross between a pill bug and a yak, the harshly-named creepers turn out to be surprisingly endearing and highly intelligent, desiring peaceful coexistence with the settlers rather than war. For all intents and purposes, they are Bong’s take on the Na’vi in Avatar, albeit far more removed from anything vaguely humanoid. It is ironic then that in fighting for this alien species, those stripped of their humanity are set on a path to regaining it, breaking free of a system which draws a hostile divide between the self and the other.

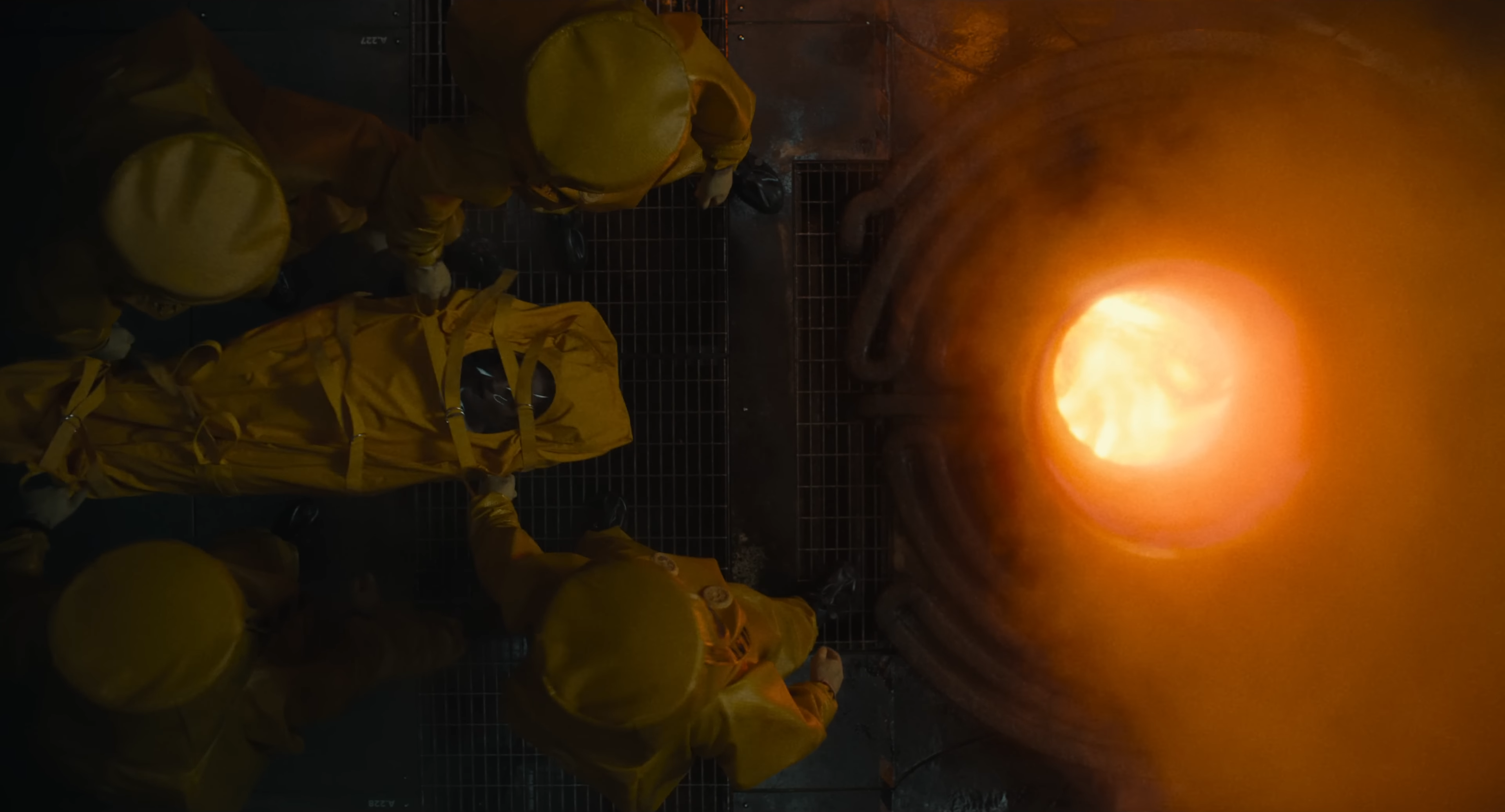

It is disappointing that the futurist production design on display isn’t always taken advantage of in Darius Khondji’s cinematography, but this does not detract from Bong’s impactful visual symbolism. The furnace where each of Mickey’s corpses are disposed regularly damns him to the pits of hell, while the implications of a human printer which guarantees his eternal servitude are chillingly reframed in the closing minutes, pondering the impossibility of permanently expunging dictators from society. Those familiar with Bong’s tendency to wield both the sledgehammer and the scalpel shouldn’t be surprised at Mickey 17’s inelegant swerve away from Parasite, yet in an era where exploitation is repackaged as progress, his satirical blend of class-conscious allegory and genre spectacle resonates all too clearly.

Mickey 17 is currently playing in cinemas.