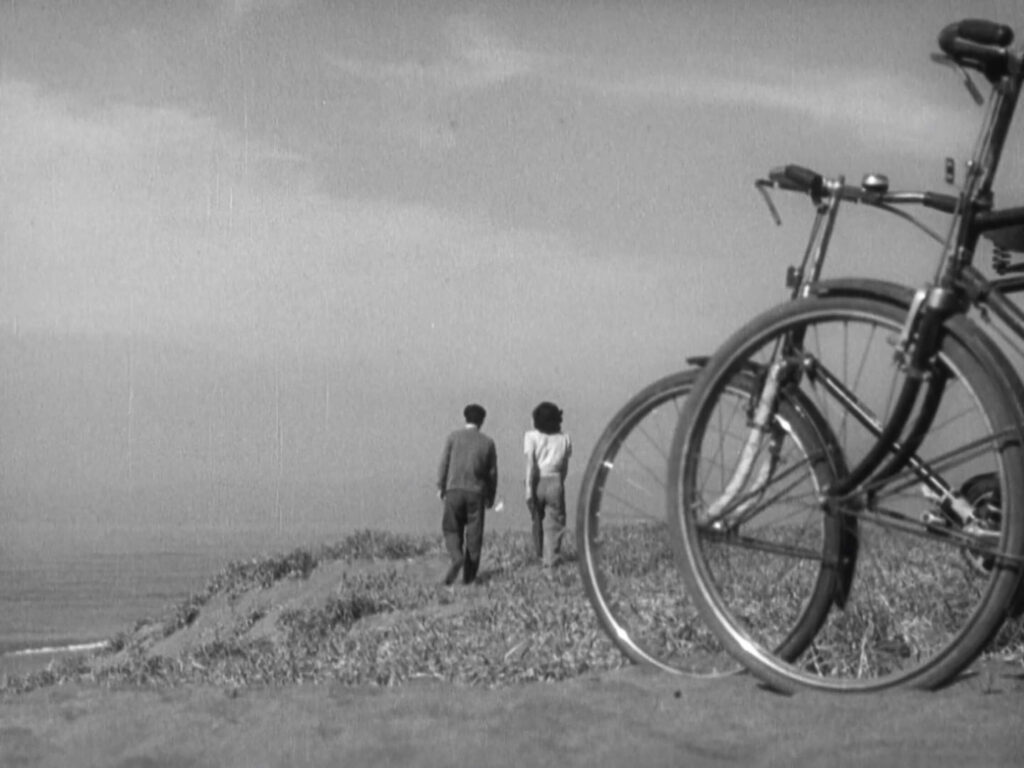

Late Spring (1949)

With Yasujirō Ozu’s contemplative editing and curated mise-en-scène guiding Late Spring’s lyrical rhythms forward, there is both profound joy and sadness to be found in its central father-daughter love, finding melancholy drama in her resistance to getting marriage and his quiet acceptance of being left behind.